Really Real Fake Centurions: Legio I Italica

The Italian legal kerfuffle over “Fake Centurions” abruptly came to make sense on my recent visit to Bologna, when I discovered the Legio I Italica camped out in the cathedral square.

The Italian legal kerfuffle over “Fake Centurions” abruptly came to make sense on my recent visit to Bologna, when I discovered the Legio I Italica camped out in the cathedral square.

Legio I Italica is a group of top quality, professional Roman Legionary reenactors, who travel around Italy by invitation, making camp in various towns and cities in order to educate Italians, young and old, about the real life of the legions and the ancient world. Their gear is superb, none of the plastic or anachronistic ornament of those who strut around Rome’s monuments. Real steel, real bronze, real leather, but more than that. These soldiers are bruised and bandaged, rough, crude, their sandals worn, their armor dented, their tunics sweat-stained.

They also include the parts of Roman gear we don’t tend to identify as Roman: a sweat-catching handkerchief around the neck, an anti-sun bandanna, broad straw sun-hats only subtly different from the hundreds for sale at street stalls a block away. Parts that reinforce the continuity between history’s dirty work and today’s, and decrease, rather than augmenting, the feeling of antiquity. Parts that should be there.

Their demeanor is perfect too, a lazy, languid casualness in interacting, both with people, and with gear, so they really feel like soldiers on their day off. “Hey, kid, wanna pull this string?” (Hands small child trigger rope for massive crossbow). “Naah, your Mom doesn’t need to help, here, just pull that.” They often just sit, doing their own thing, until curious bystanders approach them, rather than accosting.

The juxtaposition of Roman Legion with Bologna’s main square’s elaborate cathedral, Renaissance facades, medieval fortress-palaces, and the statues of popes and allegorical figures watching is, of course, fantastic.

The most outstanding element may be their variety. They don’t only include soldiers and support but all kinds of camp staff and hangers-on, everyone that might travel with a legion, including my favorite: the camp layabout who won’t do anything helpful. Here he is refusing to come help this legionary answer questions for the nice lady. Shortly he will move on to refusing to help the shoemaker, then refusing to help the cook…

The most outstanding element may be their variety. They don’t only include soldiers and support but all kinds of camp staff and hangers-on, everyone that might travel with a legion, including my favorite: the camp layabout who won’t do anything helpful. Here he is refusing to come help this legionary answer questions for the nice lady. Shortly he will move on to refusing to help the shoemaker, then refusing to help the cook…

They do have a cook, complete with samples of all sorts of noxious Roman spices and ingredients. For those not familiar, if there is one branch of human achievement whose progress has been unilaterally and consistently positive through all of human history, that branch is cooking. Excluding current perversions of too-artificial ingredients and flavor-free, chemical-plumped out-of-season vegetables (which are issues of farming and distribution rather than cuisine) food has gotten better, better, better as new combinations, techniques and ingredients have expanded the possibilities, and made it possible to leave the stopgaps of the past behind. Crude early grains became cooked grains, then flour, flat bread, bread which rose and was soft and scrumptious, eventually to such masterpieces as the cake and the croissant.

There are some left-behind recipes and ingredients that are certainly worth revisiting, but as Florentine dishes like tripe and boiled pig’s knuckles teach us, many “old-fashioned” or “rustic” dishes are code for “What we used to eat when we were under siege.” Many ingredients have faded from the world of cooking because we found better ingredients, and two-thousand-year-old Roman cooking is one step above the random plants and dead animals one would eat if trapped on a desert island. This camp cook wisely did not offer to let us taste Rue, or the infamous Garum, rotten fermented salty fish paste which the Romans slathered like ketchup on everything, even deserts. But he did have enough to smell.

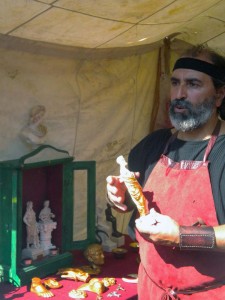

Their doctor is also superb. He’s a Greek doctor, and will happily explain that he does not want to be here with these idiotic , ignorant Romans. He studied in Athens, and in Egypt, and he has read the writings of Hippocrates, and he wants to use real medicine and perform real surgery, but nooo… all these superstitious soldiers want are charms and prayers. He prescribes sensible things like liver-based ointments and asparagus extracts, but they won’t listen to him unless he also has a shrine filled with irrelevant idols, and a winged phallus hanging from the rafters of the hospital tent. By the time you’ve listened to his rant, you realize you know what every instrument on the desk is for.

Their doctor is also superb. He’s a Greek doctor, and will happily explain that he does not want to be here with these idiotic , ignorant Romans. He studied in Athens, and in Egypt, and he has read the writings of Hippocrates, and he wants to use real medicine and perform real surgery, but nooo… all these superstitious soldiers want are charms and prayers. He prescribes sensible things like liver-based ointments and asparagus extracts, but they won’t listen to him unless he also has a shrine filled with irrelevant idols, and a winged phallus hanging from the rafters of the hospital tent. By the time you’ve listened to his rant, you realize you know what every instrument on the desk is for.

Everyone in the world should learn about Rome, but there is a unique import to teaching Italian children about the empire which was, in fact, their own. This duty the Legio I Italica takes very seriously.

All over the camp, inviting tables of Roman materials were left practically unsupervised, inviting tiny kids to begin as tiny kids do, by simply touching and exploring new objects, learning at their own pace about weight and texture, before asking Mom or Dad or a nearby captain what the heavy metal vest is for, or what the big red things are called. Adults too were invited to explore the random detritus of the camp and discover for ourselves the tools of a Roman sandal maker, or the different items necessary for the good maintenance of a shield and armor. Exploration rather than lecture was both more memorable, and more authentic-feeling as one wandered the camp receiving silent half-glares from centurions who were obviously just too lazy to shoo out these curious provincials.

The greatest change, from Rome and Florence, is that all this was in service of Italians. These legionaries are not a tourist attraction, nor interested, and nothing whatsoever is in English: conversations and banner announcements in Italian, all else in Latin.

Bologna was a perfect venue for them, a lively square, with a trickle of foreigners making the Tuscany tour, but alive with natives, families out for Sunday lunch, and visitors from other parts of Italy in town to taste Bologna’s famous tortellini, or its treasured Mortadella (Mortadella is to humble America sandwich bologna as a butter-soft mouth-watering Prosciutto is to the contents of a 7-11 ham sandwich).

A guide who works in Sicily recently described that he was taking an American around who really wanted a photo of a native old lady in traditional Sicilian dress. They ran across just such an old lady in a tiny mountain village outside Taormina, wearing a traditional black dress with headdress, and even leading a little black lamb. They stopped to ask her for a photo. Smiling, she rubbed her fingers together, asking for cash.

Italy’s dependence on tourist cash cannot be overstated. Economic discussions these days are monotonously discouraging, but it is still interesting to compare the recession woes of home to the recession woes of other lands. I chatted yesterday with a man who retired from the exhaustion of chef-dom hoping to set up business on his own in a small way.

Taxes made a restaurant prohibitive, since the taxes on electricity, gas, water, sewage, phone and property rental would, he said, have required millions in overhead, and translated to a cost of more than 300 euros per day for taxes alone for every day a small shop or restaurant was open. The more modest goal of becoming a guide still involved 200,000 euros’ investment in government licenses. With enterprise so challenging to undertake (he waxed wistfully about how miraculous it is that other countries, hint, hint, have government subsidies to help launch small businesses), it is no surprise that someone might try to make a living camping by the Colosseum in a plastic helmet, or coax what one can from passing visitors. This makes the Legio I Italica that much more admirable, as they work far from international tourist centers. They receive money from the towns that hire them, but while working they solicit and accept no tips, and work away, with the beating sun, uncomfortable armor and no pants, to make sure little Italians grow up with a dose of the real mixed among their fantasies of their glorious ancestry.

Taxes made a restaurant prohibitive, since the taxes on electricity, gas, water, sewage, phone and property rental would, he said, have required millions in overhead, and translated to a cost of more than 300 euros per day for taxes alone for every day a small shop or restaurant was open. The more modest goal of becoming a guide still involved 200,000 euros’ investment in government licenses. With enterprise so challenging to undertake (he waxed wistfully about how miraculous it is that other countries, hint, hint, have government subsidies to help launch small businesses), it is no surprise that someone might try to make a living camping by the Colosseum in a plastic helmet, or coax what one can from passing visitors. This makes the Legio I Italica that much more admirable, as they work far from international tourist centers. They receive money from the towns that hire them, but while working they solicit and accept no tips, and work away, with the beating sun, uncomfortable armor and no pants, to make sure little Italians grow up with a dose of the real mixed among their fantasies of their glorious ancestry.