Florence: Overview of Churches and Monuments

A quick review of the architectural centerpieces of Florence. Prices and hours may change arbitrarily (this is Italy, after all).

Palazzo Vecchio (Palazzo della Signoria):

Palazzo Vecchio (Palazzo della Signoria):

- The old seat of government of the Florentine Republic, later taken over as the seat of the Medici Dukes. The different parts of the building are a micro-history of Renaissance Florence right before your eyes. Going to see the outside is a must. You can pay to go inside, to see the ducal decorations, the offices where all the great humanists used to work, and Dante’s death mask, which is kept there because why not. Among the decorations are some beautiful intarsia (inlaid wood) doors with portraits of Dante and Petrarch, plus the original of Donatello’s Judith. You can also see the enormous Hall of the 500, which Savonarola had built, and its over-the-top decorations. You can’t go up the tall tower where the prison was.

- Cost: Seeing it from the outside, and entering the lower story, is free.

- Time required: 20 minutes to just look at, 2 hours for the museum.

- Hours: Changing all the time, but usually 9 am to 7 pm, but sometimes 2 pm to 7 pm, and sometimes open super late, often on Thurs or Tues.

- Website: http://www.museicivicifiorentini.it/en/palazzovecchio/

- Notes: See my discussion of it: https://www.exurbe.com/?p=37

Baptistery:

- The old heart and symbol of the city, sacred to its patron saint John the Baptist. The baptistery is right in front of the cathedral, and the oldest of the grand buildings erected to show off Florence’s affluence. The outside features the Gates of Paradise, with Ghiberti’s gilded bronze relief sculptures, one of the greatest moments in Renaissance sculpture. Seeing the outside is free, but it is worth paying to go in, because the entire interior is covered with gorgeous gold mosaics in stunning condition, including a fabulous depiction of Hell. Also Florence’s antipope is buried inside (closest thing they had to a pope before the Medici), and outside keep an eye out for the Column of St. Zenobius nearby.

- Cost: 4 or 5 euros to go inside.

- Time required: half an hour

- Hours: 12 pm to 7 pm weekdays, open 8:30 am to 2 pm on the first Saturday of the month.

- Notes: The tickets are sometimes sold at the entrance of the baptistery, but sometimes in a confusing archway to the right of it (if you stand facing the gates of paradise). People will usually point you the right way. You get a slight discount if you get the baptistery ticket along with a ticket to climb the Duomo and go to the Museo del Opera del Duomo.

Duomo (cathedral) and Belltower:

Duomo (cathedral) and Belltower:

- The grandest church in Christendom when it was built, and still so beautiful that, when you’re standing in front of it, it’s hard to believe it’s real. The outside is a must-see. The dome was the greatest engineering marvel of its day, and still astoundingly humongous. The inside is also worth seeing, with colored marble floors, high clean vaults, and the dome frescoed with a particularly excellent last judgment, with a great Hell-scape. On the right hand wall look for the tomb of Marsilio Ficino (who restored Plato the the world) and on the left the painting of Dante standing in front of Florence, Purgatory, Heaven and the gates of Hell.

- You can, separately, pay to climb the dome. It is taaaaaaaaaaaaall. Climbing it lets you see the inside between the two layers of the double dome (which is how a dome that big stays up), and lets you see the fresco on the inside of the dome up close. The view on top is spectacular but a lot of people get major height fear and vertigo up there, even people who don’t usually, due to the dome’s dizzying slant. Also the cramped area between the domes is rather claustrophobic, giving you the world-class claustrophobia-acraphobia combo!

- You can also pay to climb the belltower but it’s not hugely worth-it, unless you want to see the bells bells bells bells bells bells bells bells. In general, though, if you want to climb something, go for the Duomo.

- Cost: Free to enter the cathedral. You have to pay to climb the dome.

- Time required: Half an hour for seeing the cathedral, a couple hours for climbing the dome.

- Hours: 10:00 am to 5:00 pm, with some complicated exceptions. Check the website with an Italian friend.

- Website: http://www.operaduomo.firenze.it/monumenti/duomo.asp

- Notes: Climbing the dome has a long line a lot of the year, as does the cathedral itself even though you don’t pay; they only let a certain number of people in at a time. (Ex Urbe’s humble assistant Athan can confirm that the line is long and the climb cramped even in January.)

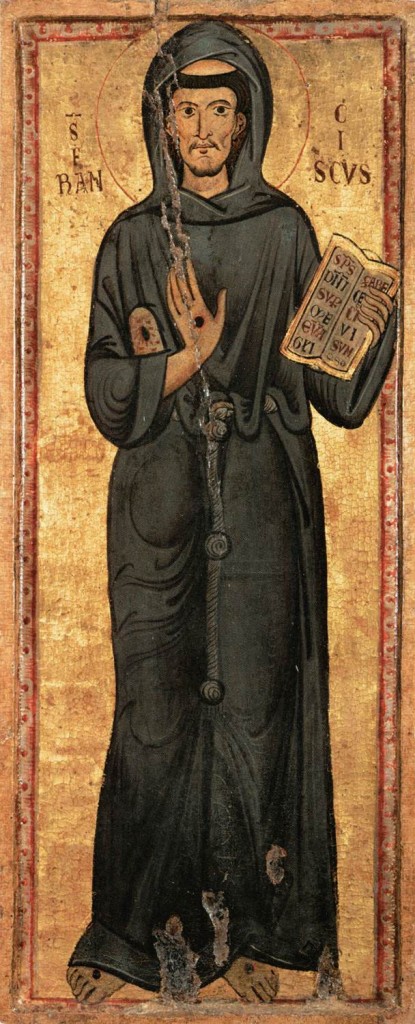

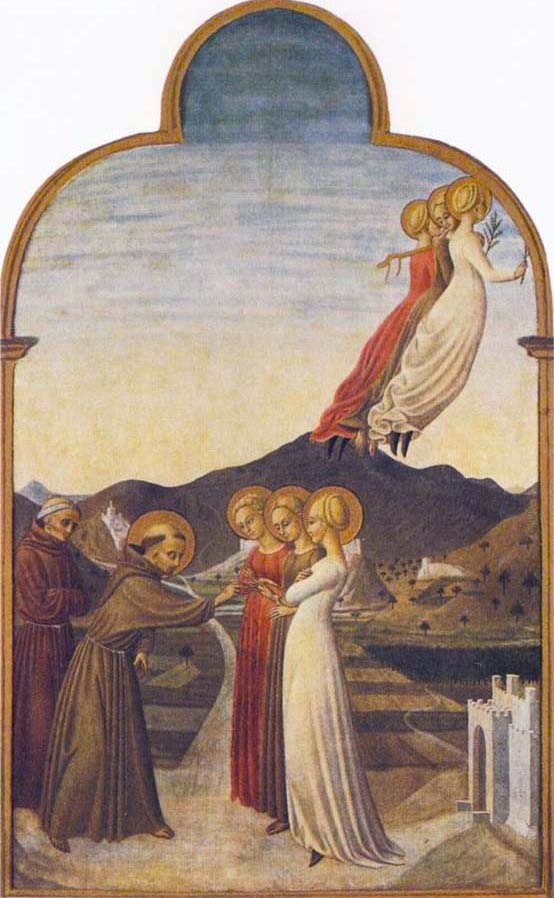

San Marco:

- No photography allowed in the monastery, so I can’t offer decent photos. This is the major Dominican monastery and church (in contrast with the Franciscans at Santa Croce). The church itself is free, while you have to pay to go to the monastery museum, but it’s only 5 euros and very worth-it.

- The church is mostly baroque at this point, but contains the tombs of the Renaissance scholars Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and Poliziano. Also a byzantine mosaic Madonna, a nice annunciation, the tomb of St. Antoninus, and an angry bronze statue of Savonarola.

- The monastery section is the real centerpiece. Every cell in the monks’ living area was frescoed by Fra Angelico, as were the refectory and other important spaces. This rare chance to see Renaissance paintings still in their original context lets you understand how they were used and interacted with in daily life. While almost every room has a crucifixion scene, each one is unique, highlighting some different emotional or theological aspect of the crucifixion, in a perfect example of how Renaissance artists moved on from the repetition of icon making to make each piece offer the viewer a unique new angle on the subject. You can also see Savonarola’s room and relics, and the room Cosimo de Medici had made for himself when he paid for the renovation of the monastery, so he could come there to have a break from public life sometimes.

- Cost: Free for the church, 4 euros for the monastery section. It is on the Friends of the Uffizi pass.

- Time required: 2+ hours

- Hours: 8:15 to 1:20 pm weekdays, 6:15 to 4:50 weekends. Closed odd numbered Sundays and even numbered Mondays.

- Website: http://www.uffizi.firenze.it/musei/?m=sanmarco

- Notes: The priest will usually glare at anyone who comes into the church and makes straight for Pico’s tomb.

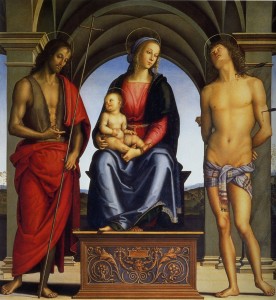

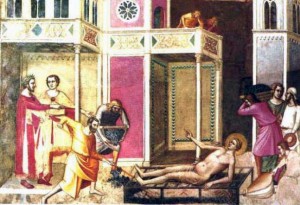

Santa Croce:

- On the East end of town, Florence’s major Franciscan monastery church came to be the major burial place for famous Florentines. Includes the tombs of Machiavelli, Galileo, Michelangelo, Fermi, Marconi (who invented the radio), Bruni (who invented the Middle Ages), the cenotaph of Dante, and dozens and dozens of other tombs crammed into every surface. Also excellent Giotto and Giotesque frescoes, and other exciting art. The orphanage it used to house taught orphans leather working, and it still contains a leather working school. Also contains one of the surviving tunics of St. Francis of Assisi.

- Cost: 5 euros! Expensive!

- Time required: 2 hours

- Hours: 9:30 AM to 5 PM except Sundays, when it opens at 2

- Website: http://www.operadisantacroce.it/

- Notes: It tends to be quite cold inside.

Ponte Vecchio:

Ponte Vecchio:

- The old bridge, covered with tiny jewelry shops. This has been the heart of Florence’s gold trade for a long time, and is incidentally one of the most valuable shopping strips on Earth. At night the tiny little shops lock themselves up in wooden shutters and look like giant treasure chests, which is really what they are. The view of this bridge from the next bridge down (Ponte Santa Trinita) is also worth seeing. Be sure, while on the bridge, to greet the statue monument of the incomparable Benvenuto Cellini, Florence’s great master goldsmith/ sculptor/ duelist/ engineer/ necromancer/ multiple-murderer, who wrote one of humanity’s truly great autobiographies.

- Cost: Free.

- Time required: half an hour, more if you want to shop

- Hours: Shops shut around sunset.

San Lorenzo:

San Lorenzo:

- My photos do not do this church justice, but they don’t let you take pictures inside. San Lorenzo is a little complicated because you have to pay separately to go in the different areas:

- The main part of the church (which costs 3.5o euros) is a mathematically-harmonious, high Renaissance neoclassical church full of geometry and hints of neoPlatonism. I recommend going in it after Santa Croce and Orsanmichele, since the contrast of its lofty, light-filled spaces and rounded arches gives you a vivid sense of how much architecture has changed in so little time. Here you can see the excellent tomb of Cosimo de Medici (il vecchio), and some other early Medici tombs, as well as some Donatello reliefs and the remains of Saint Caesonius (no one knows who he is or how he got there, but he’s clearly labeled as a saint, so no one’s willing to move him). This ticket also gets you into the crypt below the church, where you can see the bottom of Cosimo’s tomb, and a collection of really gaudy reliquaries.

- Separately, the library attached to the cloister courtyard at the left of the church (which also costs 3.50 euros, but you can get a combined ticket to it and the church for 6) contains the reading room with the desks where the great Laurenziana library was housed. It is very much a scholarly pilgrimage spot to see one of the first great houses of the return of ancient learning. The old reading desks are still there where the books were chained, and still labeled with the individual manuscripts. To get in you also get to (or rather have to) go up Michelangelo’s scary scary staircase. The library periodically has small exhibits of exciting manuscripts, most recently on surgery, and on the oldest surviving copy of Virgil. The library is only open in the morning! Its gift shop sells some fun things including a lenscloth decorated with a reproduction of the illuminated frontispiece of the Medici dedication copy of Ficino’s translation of Plato – ultimate history/philosophy nerd collectable.

- Separately, the Medici Chapels in the back of San Lorenzo (under its big dome; costs 5 euros, but is on the Friends of the Uffizi card, unlike the other two [why?!]) contain the later Medici tombs, those of Lorenzo de Medici, his brother, the next generation of Medici, and the Medici dukes. The earlier Medici tombs here have some Michelangelo sculptures on them, while the later ones are in a ridiculously over-the-top baroque colored marble chapel which knocks you breathless with its unbridled and rather tasteless opulence. One friend I visited with subtitled the chapel: “Baroque: UR doin’ it WRONG!” An excellent excercise in trying to grapple with the evolution of taste, and why certain eras’ taste matches our own while others don’t. Also you get to see more over-the-top sparkly reliquaries.

- Hours: Different for each bit.

Orsanmichele:

Orsanmichele:

- The former grain market and grain storage building at the heart of the city was turned into a church when an icon of the Madonna there started working miracles. Because it was the official church of the merchant guilds of Florence, the different guilds competed to supply the most expensive decoration for it, so the outside is covered with fabulous statues, each with the symbols of its guild above and below. Seeing the outside is quick and easy. Seeing the inside is trickier and not always worth cramming into your schedule, but the inside is also beautiful, a very medieval feeling, with saints painted on every surface. A museum above (open rarely, mainly Mondays) holds the original sculptures, which have been replaced on the outside with copies for their own safety. But since the sculptures were designed to be seen in their niches, the copies in situ look better than the displaced originals in my opinion.

- Cost: Free

- Time required: half an hour

- Hours: 10 am to 5 pm. Closed on Monday.

- Notes: Occasionally hosts concerts. On the outside is a booth where you can get tickets to the Uffizi without waiting in the Uffizi line.

Mercato Centrale & Mercato San Ambrosio:

Mercato Centrale & Mercato San Ambrosio:

- Not historic, but the two great farmer’s markets of the city are definitely worth visiting, and great for both lunch and souvenir shopping. Cheese, salumi, spices, sauces, fruits, veggies, oil, vinegar, truffle products… The Mercato Centrale (near San Lorenzo) has more touristy things and things to take home, while San Ambrosio has more things to eat right now or cook at home, but both have both. At the Mercato Centrale I particularly recommend eating fresh pasta at Pork’s (order tagliatelle with asparagus, or all’ Amatriciana (with tomato, onion and bacon) or tortellini with cream and ham (prosciutto e panna)), and/or having a porchetta sandwich. You can also try tripe or lampredotto if you’re brave.

- Cost: Free

- Time required: 1+ hours

- Hours: Morning through early afternoon.

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)