2018 Campbell Speech, How New Authors Expand Fields (+Censorship, Manga)

This year I was honored to present the 2018 John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer at Worldcon’s Hugo Awards Ceremony, and several people have asked me to post my presentation speech, in which I used Japanese examples to talk about the invaluable impact of new authors expanding the breadth of what gets explored in genre fiction’s long conversation. Here is the speech, followed by some expanded comments:

The Speech:

First awarded in 1973, this award was named for John W. Campbell, the celebrated editor of Astounding and Analog who introduced many beloved new authors to the field. This is not a Hugo award, but is sponsored by Dell Magazines, and administered by Worldcon. Spring Schoenhuth of Springtime Studios created the Campbell pin, and the tiara made by Amanda Downum was added in 2005/2006. This award is unusual for considering short fiction and novels together, providing a cross-section of innovation in the field, and, often, offering a first personal welcome to new writers unfamiliar with the social world of fandom.

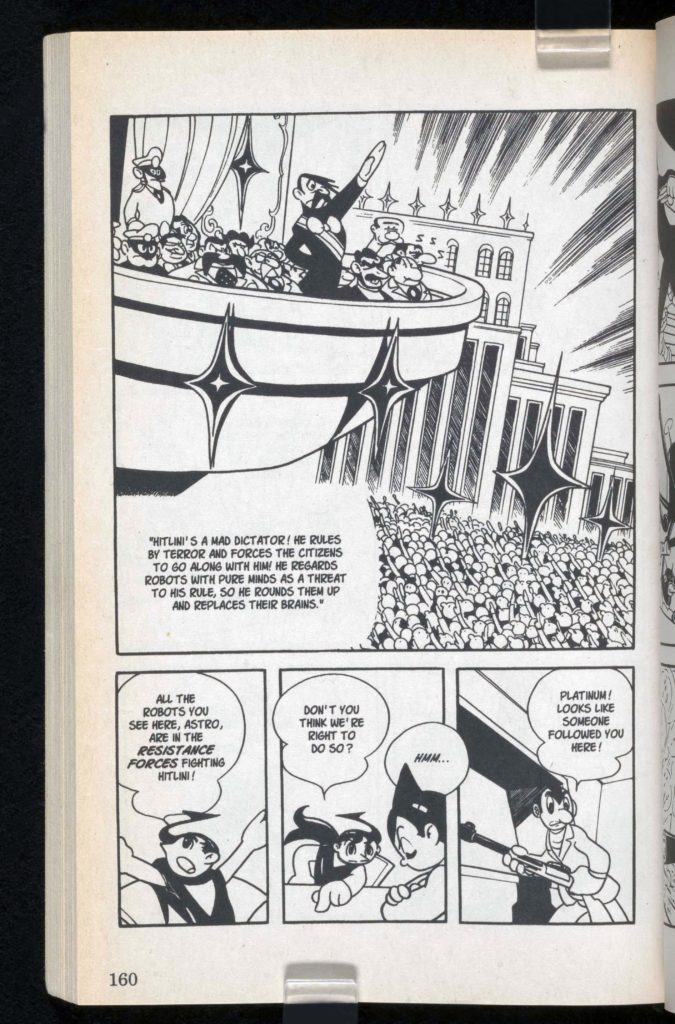

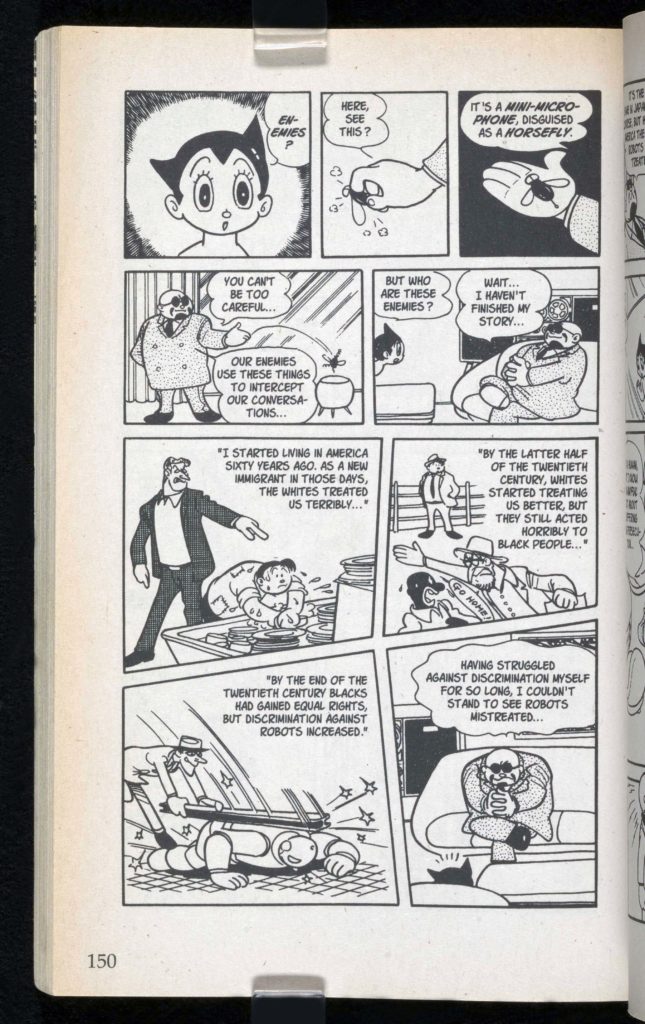

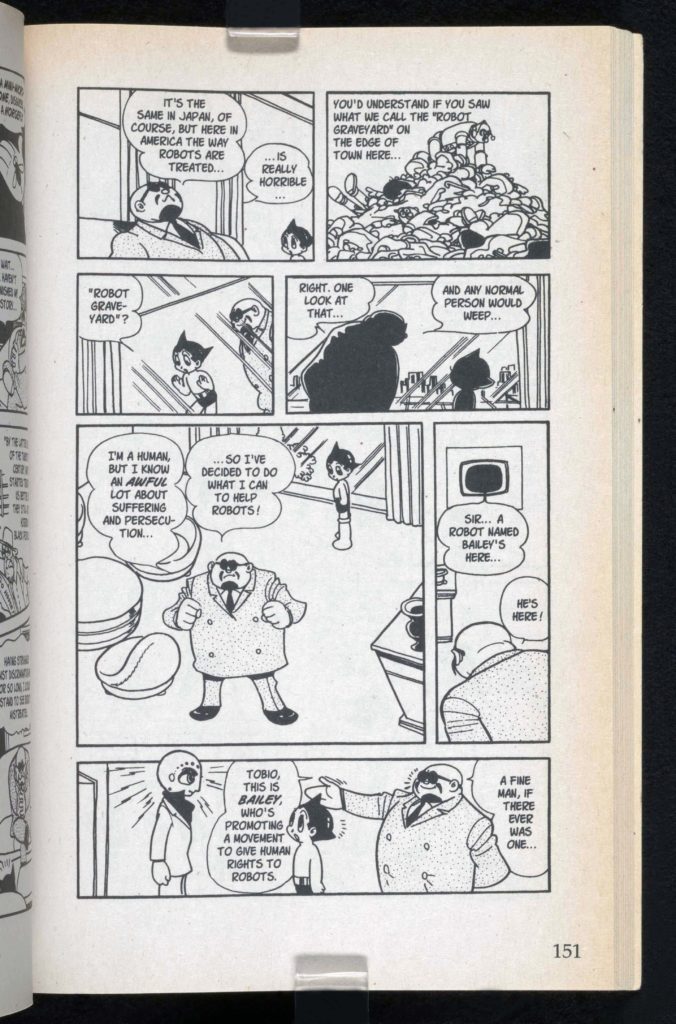

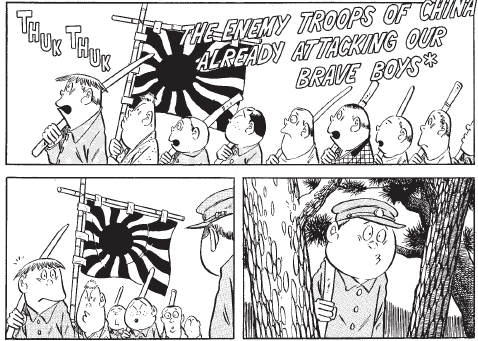

I’m currently curating an exhibit on the history of censorship around the world, and one section of the exhibit keeps coming to mind as I consider the Campbell Award. Immediately after World War II, in Japan authors and journalists were effectively forbidden to talk about the war, due to censorship exercised by both the reformed Japanese government and American occupation forces. This left a generation of kids desperate to understand the events which had shattered their world and families, but with no one willing to have that conversation, and no books to turn to. Enter Osamu Tezuka whose 1952 Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu, 1952-68) bypassed censors who saw it as merely a kids’ science fiction story, while it depicted a civil rights movement for robot A.Is., including anti-robot hate-crimes, hate-motivated international wars, nuclear bombs, and the rise of the robot-hating dictator “Hitlini.”

Tezuka’s science fiction became the tool a generation used to understand the roots of World War II and how to work toward a more peaceful and cooperative future, but what makes this relevant to the Campbell Award is the next step. Many autobiographies of those who were kids in Japan in the 1950s describe reading and re-reading Tezuka’s early science fiction until the cheap paperbacks fell apart, but by the later 1960s these same young readers became young authors, like Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Keiji Nakazawa, and their peers. They in turn led a movement to push the envelope of what could be depicted in popular genre fiction in Japan, writing grittier more adult works, battling censorship and backlash, and ultimately opening a space for more serious genre fiction. These new voices didn’t just contribute their works, they changed speculative fiction to let Tezuka and other authors they had long looked up to write new works too, finally depicting the war directly, and producing some of the best works of their careers, including Tezuka’s Buddhist science fiction masterpiece Phoenix.

These authors I’m discussing are all manga authors, comic book authors, but the difference between prose and comics doesn’t matter here, their world like ours was and is a self-conscious community of speculative fiction readers and writers dedicated to imagining different presents, pasts, and futures, and thereby advancing a conversation which injects imagination, hope, and caution into our real world efforts to and build the best future possible. It is in that spirit that the John W. Campbell award welcomes to our field not only today’s new voices but the ways that these voices will change the field, stimulating new responses from everybody, from those like John Varley and George R. R. Martin who were Campbell finalists more than forty years ago, to next year’s finalists. This year’s finalists are Katherine Arden, Sarah Kuhn, Jeannette Ng, Vina Jie-Min Prasad, Rebecca Roanhorse, and Rivers Solomon.

Further Details:

The examples I discussed in this speech come from my exhibit’s case on the censorship of comic books and graphic novels, which are targeted by censorship more often than text fiction because of their visual format (which makes obscenity charges easier to advance), their association with children, and the power of political cartoons.

Tezuka’s manga I discuss in the exhibit with the chilling title “Childhood Without Books” since during World War II a generation of Japanese kids grow up in a broken school system which had all but shut down or been transformed into a military pre-training program, while censored presses produced only war propaganda, and Japan even had a ban on “frivolous literature” which generally meant anything that wasn’t for the war. In effect, a generation of kids grew up with no access to literature, and plunged straight from that to the new era of post-war censorship. Numerous autobiographies by members of this generation vividly recount the arrival of the first bright, colorful books by “God of Manga” Osamu Tezuka, such as New Treasure Island, Lost World, Nextworld, and above all Astro Boy whose depictions of anti-robot voter suppression tactics are very powerful today, while its repeated engagement nuclear bombs and other weapons of mass destruction were, for adults and kids alike, often the first and only available literary discussion of nuclear warfare. Tezuka also made a point of discussing racism as a global issue, and Astro Boy depicts lynch mobs in America, the Cambodian genocide, and post-colonial exploitation in Africa.

Thus, while being perceived as “for kids” often brings comics under extra fire, in the case of Astro Boy, censors ignored a mere science fiction comic, which let Tezuka kick start the conversation about the mistakes of the past and the possibilities of a better future.

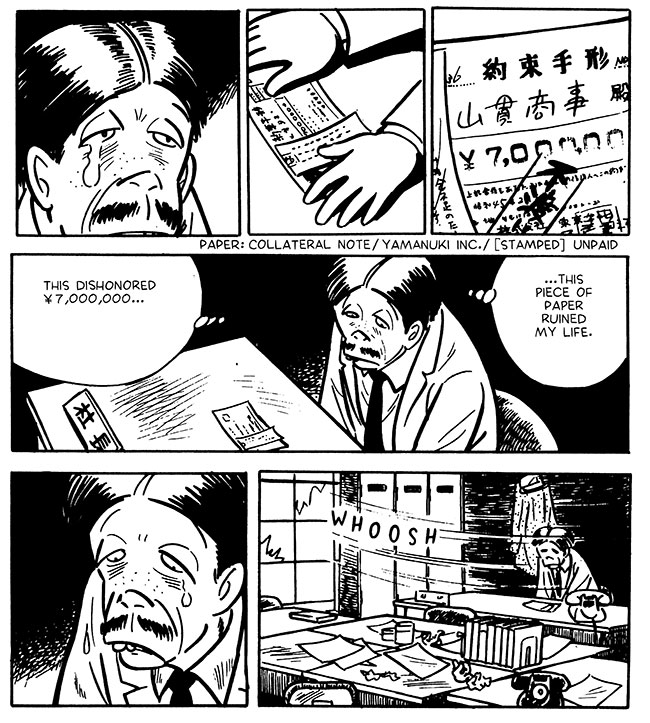

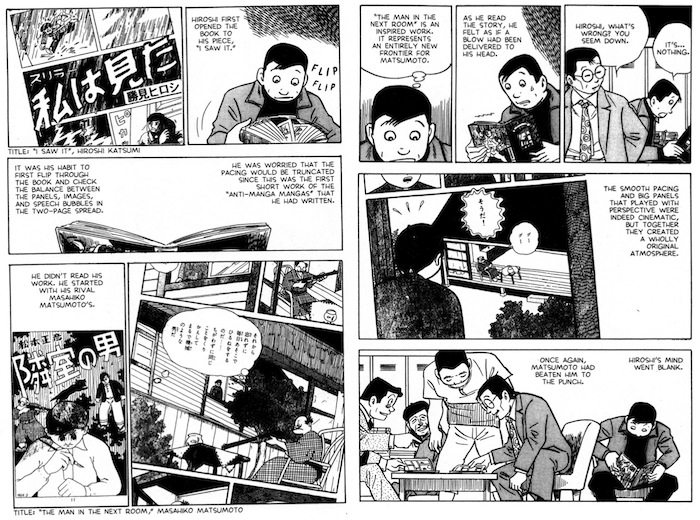

Making Room for Adults: One young reader who read and reread Tezuka’s early manga until they fell apart was Yoshihiro Tatsumi, whose autobiography A Drifting Life begins with Tezuka’s impact on him in his early post-war years. As Tatsumi himself began to publish manga in the 1950s-70s, Japan experienced its own wave of public and parental outrage about comics harming children similar to that which had affected the English-speaking world slightly earlier. Since the Japanese word for comic books, manga, literally means “whimsical pictures” critics argued that manga must by definition be light and funny. Tatsumi coined the alternate term gekiga (“dramatic pictures”) adopted by a wave of serious and provocative authors who set out to depict serious dramatic topics, such as crime stories, suicide, sexuality, prostitution, the debt crisis, alienation, the psychology of evil, and the dark and uncomfortable social issues and tensions affecting Japanese society.

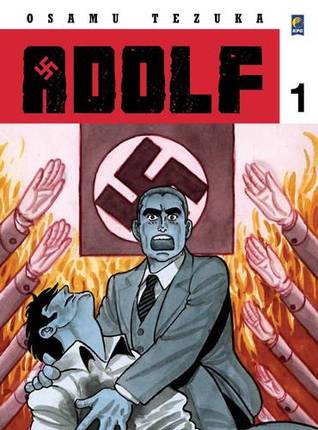

By the 1970s, the efforts of Tatsumi and his peers to make space for mature manga helped to expand the range of what artists dared to depict, contributing to the loosening of censorship and social pressure, which in turn let the the authors Tatsumi and others had looked up to as children to finally treat the war directly. Thus Tatsumi’s efforts moving forward from his childhood model Osamu Tezuka in turn paved the way for Tezuka to finally own including Message to Adolf which depicts how racism gradually poisons individuals and society, Ayako which depicts the degeneration of traditional Japanese society during the post-war occupation, MW which depicts government corruption and the human impact of weapons of mass destruction, sections of his beloved medical drama Black Jack which treat war and exploitation, Ode to Kirihito which treats medical dehumanization and apartheid in South Africa, Alabaster which treats ideas of race and beauty in the USA, and his epic Phoenix, considered one of the great masterpieces of the manga world.

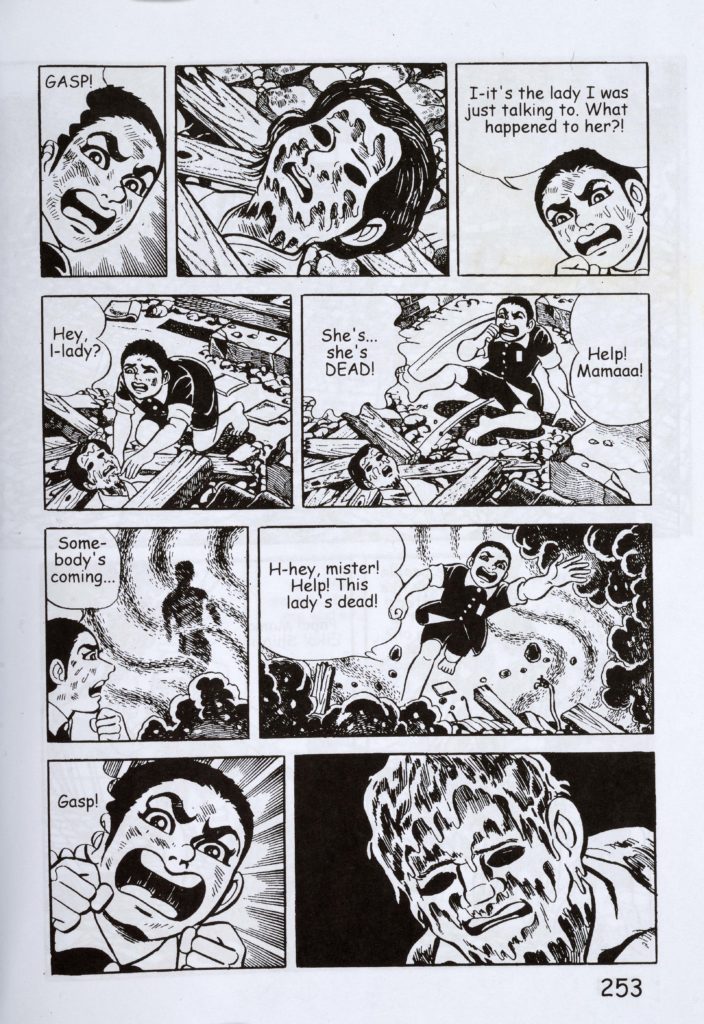

Another of Tezuka’s avid early readers was Hiroshima survivor Keiji Nakazawa, who found in art and manga hope for a universal medium which could let his pleas for peace and nuclear disarmament cross language barriers. Many of the grotesque images of gory melting faces in Nakazawa’s harrowing autobiography Barefoot Gen are indistinguishable from the imagery in violent horror comics advocates of comics censorship so often denounce as harmful to children.

Our impulse to place political works like Barefoot Gen in a separate category from graphic horror or pornography despite their identical visual content is reflected in many governments’ obscenity laws, which ban vaguely-defined “obscene” or “indecent” content and often demand that works accused obscenity prove they have “artistic merit” to refute the charge, a rare situation where even legal systems with “innocent until proven guilty” standards put the burden of proof on the defendant. Some modern democracies which have state censorship, such as New Zealand, have worked to improve this by creating legislation which defines very clearly what can be censored (for example depictions of sexual exploitation of minors, or of extreme torture) rather than banning “indecent” content in the abstract. (I strongly recommend the New Zealand Chief Censors’ endlessly fascinating censorship ratings office blog which offers a vivid portrait of the trends in modern censorship, and what censorship would probably look like in the USA without the First Amendment).

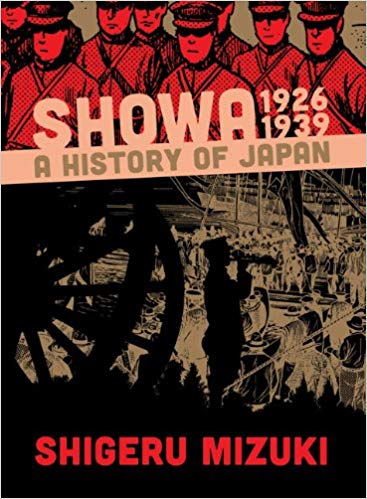

If you’re interested in looking at some of these works, beyond Astro Boy, my top recommendations are Tezuka’s Message to Adolf and the work of another giant of the early post-war, Shigeru Mizuki, best known for his earlier Kitaro series which collects Japanese oral tradition yokai ghost stories. After the efforts of Tatsumi and others broadened the scope of what manga was allowed to depict, Mizuki published his magnificent Showa: a History of Japan, recently published in English by Drawn & Quarterly.

The first volume depicts the lead up to WWII in the 1920s-30s, and is fascinating to compare to the current political world, since it shows how Japanese society was became gradually more militarized and toxic due to tiny incremental short-term political and social decisions which feel very much like many one sees today, but paralleled by severe restrictions on speech and suppression of active resistance different from what one sees today. Ferociously critical of Japan’s government and warmongers, Mizuki’s history is also autobiography, depicting himself as a child, and how the day to day games kids played on the street became more violent and military, playing soldier instead of house, as the society drifted toward fascism.

It’s an extraordinarily powerful read, and particularly captures how, parallel to political events, moments of celebrity controversy and sensational news reflect and propel cultural shifts – think of how 100 years from now someone writing a history of the rise of America’s alt right movement would not include Milo Yiannopoulos, who had no demonstrable direct political role, yet for those living on the ground in this era he was clearly a factor/ indicator/ ingredient in the tensions of the times. Mizuki includes incidents and figures like that which parallel the political events and his family’s experiences, recreating the on-the-ground experience in a way unlike any other history I’ve read. I can’t recommend it enough to anyone interested in what fascism’s rise can teach us about today, and about how cultures change.

2 Responses to “2018 Campbell Speech, How New Authors Expand Fields (+Censorship, Manga)”

-

Sadly the NZ censors seem to regard twitter as superseding rss so there’s no feed. I’m not sure why they even bother with a blog (although their blog posts are longer than 140 characters… maybe they aren’t good at twitter either?).

I think drowning out other voices is both sufficient and necessary today – there are too many channels of communication for censorship to be widely useful. But simply spamming works almost as well – trying to find useful information is hard when most search results are poisoned (or simply “reflect user preferences” should you ever want to leave your private bubble).

-

I’m so glad to have read this, so thank you to whomever(s) the persons were urging you to post it, and thank you for taking the time to expand on it. Absolutely an excellent way to frame the Campbell.