Resistance when the Tyrant is in Power: Florence’s Vasari Corridor

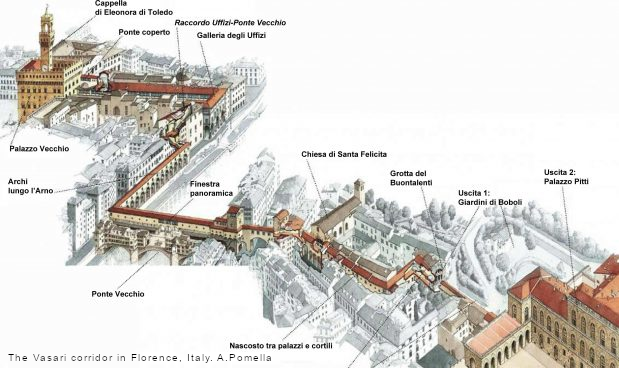

Let’s talk about resistance after a conqueror takes power. Specifically let’s talk about this bendy yellow building, and what it shows us about the moment the Florentine Republic finally fell to its kleptocratic/proto-capitalist banking-fortune Medici conquerors.

(Originally a Bluesky thread, part of my countdown to the release of Inventing the Renaissance)

In a post last week, I talked about how Renaissance towns used to be full of tall stone towers, built by rich families as mini-fortresses, & Florence got sick of people hiding in their fireproof towers while setting fire to rivals’ houses & letting things burn, so they made everyone knock the tops off.

Centuries later, the stubs of former towers were still conspicuous, and owning one was a mark of prestige, that you were rich & powerful *before* the tower ban. Tower nubs symbolized patrimony and stability. With which we can now recognize our yellow thing going around one of these nubs. Why?

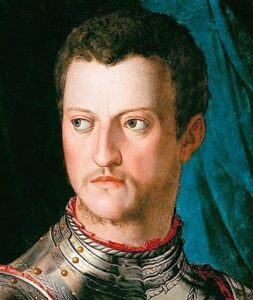

The iconic Vasari Corridor was built by a conqueror who feared his people. This lovely yellow walkway over the bridge connected the old seat of government (which he symbolically had to occupy) to the new palace where he lived, keeping him from assassination behind solid walls.

It was an architectural show of force, as all the families with property in the way were pressured to submit to the new duke’s demand to let him build his walkway over their roofs or even through their homes. It was also a show of fear, perhaps best personified by the fact that

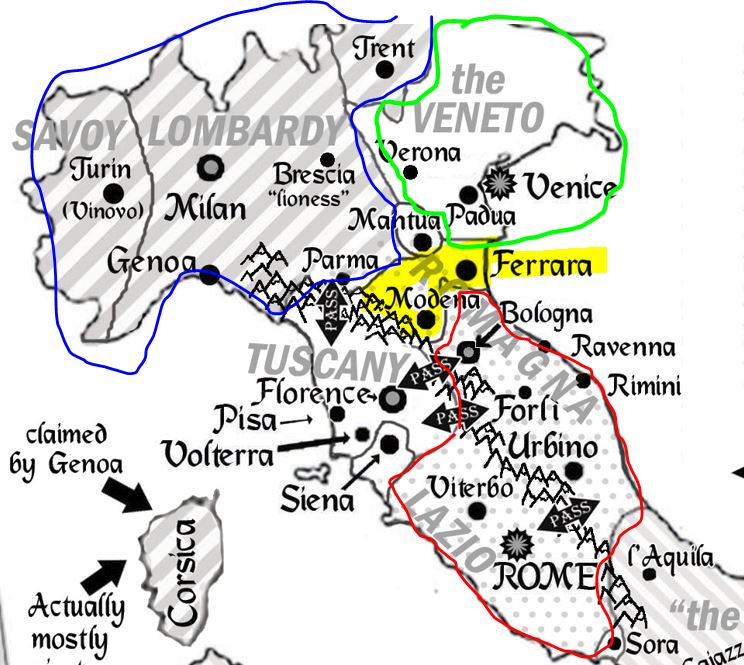

around the same time that Duke Cosimo built this fortified commuter lane to avoid his people, his neighbor Duke Alfonso d’Este of Ferrara used to walk around his city buck naked (with his dick in one hand & a sword in the other) to show off his confidence that no one dared touch a d’Este.

The d’Este were a *very* blue blooded old family, stably in power for generations, propped up by Venice, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the papacy who all wanted stability in the duchy that was the buffer zone between their three empires, minimizing direct war.

In contrast, the Medici were mere merchant scum, commoner equals of their neighbors who, back when everyone important in Florence had a tower, hadn’t had an impressive one. Bowing before a noble-blooded prince made sense to people at the time, before that family down the street?

Machiavelli said if people are deeply invested in an institution they fight for it, so places used to monarchy (like Milan) if they became republics yield to new conquerors easily (Milan did in 1450) but peoples who truly love their would never stop fighting for their ancient liberty.

Florence did fight the ducal takeover. Cellini’s Perseus statue, the topic of my first thread in this series, commemorated Duke Cosimo crushing of one violent uprising, & his desire to cast the severed heads of his enemies in eternal bronze was a show of force, but also fear.

When Duke Cosimo wanted to build his elevated private commuter tunnel, those heads on pikes were fresh memories. Most neighbors yielded to his architectural conquest, but there in his way was one old tower nub, cramped, unfashionable, cold, but patrimony of the Mannelli family who… were descended from the Roman Manlii family who’d had a consul as early as 480 BC, peers of Cicero and Caesar, who’d already owned the tower a century when Boccaccio’s friend Francesco Mannelli lived in it during the Black Death, 200 years before Duke Cosimo took power.

So when the duke unveiled his plans to blast a hole through it, the Mannelli told the young conqueror to get stuffed. Cosimo knew if he violated this symbol of ancient patrimony, every *other* propertied family would turn on him. The conqueror didn’t dare cross that line.

This wasn’t idealistic resistance; it came from one of the most oligarchic and entrenched of social forces: property rights. But it was resistance, and it worked. Around the tower the corridor went. Every generation thereafter pointed to it as a place the people drew the line, and won.

This is not a story of the kind of resistance that groundswells and overthrows the tyrants. The Medici stayed in power until the family died out, they were never overthrown. But they were *kept in check.* A line the conqueror doesn’t dare cross is a powerful line, that protects much behind it.

Stories of revolution are dramatic and cathartic, but we also need stories like this, of resistance *under tyranny* that drew a line, *reducing harm* even while tyrant stayed. Nor was this the only time Florence drew such a line.

Rewinding a century, the Medici rose to power around 1430 through a combination of cunning, cash & cultural soft power under Cosimo the Elder the great-great-great-grandfather of the Duke Cosimo. Many times in that century Florence drew the line.

They drew it violently with uprisings or assassination attempts in 1433, 1466, 1478, 1494, 1430, 1437 etc., and more quietly many times between through moments of resistance like the Mannelli telling the conqueror he and his corridor to (literally) get bent (around their tower).

The tale of resistance told by the Mannelli Tower isn’t one of revolution, it’s one of slowing down the shifting baseline. The baseline did keep shifting, less liberty for all and more power for the conquerors, but it shifted * slowly*, and many lives and rights sheltered behind that line. If we define victory as preserving the republic, there’s no happy ending, the Medici won. But if their conquest started in 1430 and they still didn’t dare pierce a symbolic tower 130 years later, that is a lot of slowing the baseline compared to what Florence’s conquered neighbors endured. Slowing the baseline shift meant many generations of Medici being careful, respecting core rights, while Alfonso d’Este didn’t just parade around Ferrara buck naked, he had his artists thrown in the dungeon if he thought they weren’t painting fast enough.

Machiavelli said peoples who treasure their liberties can preserve them even through long stretches of tyranny. That it’s peoples like 1450 Milan who yield quickly to the tyrant and don’t try to hold the line who lose their liberty completely. He wasn’t wrong.

We don’t like resistance stories without a cathartic revolution, they don’t feel like blowing up the Death Star. They feel like loss. They’re not. We need to revisit these worst case scenarios to see that, even when resistance didn’t *win* it did *work*. It saved lives & livelihoods.

Florence’s republic didn’t fall to the Medici only once, it kicked them out in 1433, in 1494, in 1512, in 1530, it took many conquests. But even when it *was* the worst case, the final fall, resistance kept Florence a place that with noticeably more liberty than its neighbors.

No one in Florence knew which republic was the last republic, not in 1430, 1478, 1494, 1512, or 1530, but they did know *all* resistance held the line and preserved liberties. Partial victory is powerful. We must remember that.

(To learn more “Inventing the Renaissance” comes out in a few weeks!)

2 Responses to “Resistance when the Tyrant is in Power: Florence’s Vasari Corridor”

-

Counting the days until my local indie bookstore notifies me this book is waiting for me! Wow, this article is so needed these days. Thank you for all your hard work and insightful analysis!

-

Was watching a YouTube video called “Dark Gothic MAGA: How Tech Billionaires Plan to Destroy America,” and your “Too Like The Lightning” books may end up being prophetic. Except instead of nations we can opt in and out of based on values, they want each nation to be a company you must own shares in – and if you’re too poor, you can be prison labor or even biofuel. And the instigating moment isn’t a religious war, but billionaires purposefully and strategically eroding nation states so they personally can shore up weath, power and land to last past the upcoming end of late stage capitalism.. I’m keeping an eye on your writing forever from now on, see what else you predict…