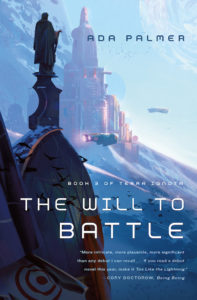

On 11th January 2018, Ada did a marathon “Ask Me Anything” session on Reddit. This post collects the questions and answers that are about Hives and bash’es in the Terra Ignota world. There may be minor spoilers, but I’m not reproducing the specific spoilers that were marked as such (partly because they’re impossible to cut and paste…) I’ve done some rearranging to put the questions into related topics just to make it more coherent to read.

Hives

Hives

Infovorematt: I get that Hives are non-geographic but how does that work in practise? If my Hive lets me smoke cannabis what if I’m in a Mason-majority city (no way they are ok with weed!) can I still light up? What if I’m visiting my humanist friends ‘bash? Is all private property (houses, malls, shops, etc) aligned to a Hive and subject to their rules and laws? There must be a bit of tension and culture clashes in public places. Strict Masons being weirded out by hippy-dippy Cousins. Cousins being uncomfortable when a Mason spanks their kids etc

Ada: Cities and some areas have individual geographic regulations passed in that area, as the cars cheerfully tell us every time we land. If you were a Humanist and smoked cannabis in a town in an area that banned it, like Lagos, Cambodia, or Myanmar (regions with a Cousin majority), then you’d be guilty of breaking local laws and could be charged by the city. Your Hive would pay a fine to the city and then impose on you whatever punishment the Hive considered appropriate, which is often an equally sized fine, but sometimes something different. It’s similar if you commit murder—your Hive pays a fine to the other Hive and then your Hive punishes you, unless your Hive has made a special deal as all the Hives have with the Utopians who reduce the fine the other Hive pays if the other Hive enforces Modo Mundo (other political favors were also promised by Utopia in return for this concession.) Private property like houses is restricted by city regulations and by Hive regulations IF it’s a one-Hive bash’, but only city regulations if it’s mixed. There can be culture clashes in public places, which is why most cities have major districts dominated by particular Hives, like the Utopian districts we see.

Infovorematt: How easy is it to create a hive? Is the small number a likely outcome or just easier from a narrative point of view

Infovorematt: How easy is it to create a hive? Is the small number a likely outcome or just easier from a narrative point of view

Early in the process, in the 2200s when the Hive system was new, it was comparatively easy to found a Hive and people expected there to be lots and lots, so there were dozens. Now it’s very hard, since with the megahives that have formed from mergers no one takes a new tiny one seriously. So we’re seeing a last man standing stage of a slow development.

Delduthling: Did you have ideas for Hives that got scrapped during the world-building process?Are there any historic Hives we haven’t heard of yet?

Ada: Yes I have some clear ideas of Hives that existed at the beginning but didn’t last. One of the main ones is OBP, “One Big Party” which merged with the Olympians to form the Humanists. The Olympians started as a transit network to take sports fans to games, and OBP was the same for concerts and theater and art and museums, so people could zip around the world to see singers, or Shakespeare, or visit a gallery. They shared their excitement about excellence, and figures like Ganymede more embody OBP than the Humanists. Others may or may not get mentions in book 4, we’ll see.

Factitious: How does having exclusive Hive languages work with mobility between Hives being so important? Do ex-Mason Humanists just politely pretend not to understand Latin?

Ada: Yes, when you switch Hive you are expected to stop speaking that language, and to politely refrain from eavesdropping on conversations in that language. The hope is that it will wither in time. Similarly for kids who haven’t yet joined a Hive, they inevitably hear the Hive language being spoken at home by their parents, i.e. young Martin Guildbreaker hears people speaking Latin all the time and learns to understand it easily as kids do, but kids are discouraged from speaking the Hive language until adulthood. Unless it’s a strat language too, i.e. a young French kid would speak French at home in addition to English despite not yet being a member of the European Hive, and a young Spaniard Spanish etc. becuase it’s a strat language, as with Mycroft speaking Greek.

Subbak: So is it frowned upon for someone (outside of professional translators and interpreters) to learn a language that is not the language of their Hive or nation-strat?

Ada: Yes, it’s considered uncomfortable, breaking a taboo. We see this in Mycroft’s guilt about using his Japanese in chapter 3.

Factitious: Did the Hive demographic chart in TLTL, which was described as being of world population, count Minors? If so, how? Did it count people on reservations?

The Hive demography doesn’t count anyone who has not yet taken the Adulthood Competency Exam, nor does it count people on reservations. So we don’t know how large the population of Reservations is.

Adult Competency Exam

MayColvin: What kinds of things are tested on the Adulthood Competency Exam? Has this changed over time since the exam was instituted as the marker of legal majority?

Ada: The Adulthood Competency Exam has a lot of moral reasoning questions, the point being to make sure you can do complex adult decision-making. So things like more elaborate versions of the Trolly Problem, with no correct answer, just asking you to articulate an answer to make sure it’s a sophisticated one that demonstrates you can make intelligent political decisions, and are mature enough not to be taken advantage of. There are also lots of versions. While Romanova’s office administers a basic one, as the Charter specifies any organization can offer one if the Alliance office confirms its equivalency, so every Hive has a version, and some strats have versions in their own languages, and there are also lots of options for format to make it easier for people with different disabiltiies. All versions involve an oral exam, and many have only an oral exam while others have an oral and written component; only the EU offers a written-only option. The Brillest one is really strange and you’re not really fully aware it’s going on most of the time.

Factitious: What options do Deaf people have for the Adulthood Competency Exam? Is there a Deaf strat that offers a version in sign language?

Ada: Deafness is less common do to medical advances, and sign is uncommon since voice-to-text is so good that you can program your tracker put simultaneous subtitles in your lenses as people are talking. The system struggles with homonyms so is imperfect, and sign is still used in some places, but the voice-to-text system is more ubiquitous. If you wanted a sign language ACE it would be offered by Romanova, the Cousins, and the Europeans.

Clothes

Clothes

Subbak: How enforced is the “Clothing as Communication” thing? Would it be illegal for a Humanist to wear a Utopian coat in public because they thought it was cool? Or an armband of a nation-strat you don’t belong in?

Ada: It’s enforced by cultural pressure rather than law, so people don’t do it much just as today people don’t go into the office dressed in a bathrobe much. It makes everyone uncomfortable. In a few circumstances you can get in legal trouble if you’ve masqueraded as a Member of another Hive for purposes of taking advantage of people, such as a journalist masquerading as one Hive to interview someone in bad faith by tricking them into thinking it’s a fellow Hive Member, or someone dressing as a Hive to go to a Hive Member only event. But when it’s for innocent purposes it’s done, certainly for dress-up parties, for acting on stage, and Sniper dresses as all the Hives sometimes for play.

Subbak: Can you describe how Mason and European suits differ?

Ada: European suits have more elements we associate with the pre-modern world, so more elaborate tailoring, long rows of buttons, waistcoats sometimes, tails or flared parts in the back, etc. They’re also a bit more wide-ranging, objects of fashion, while Mason suits are more standardized.

Factitious: Do Brillists who just plain don’t like wearing sweaters have a good alternative?

Yes! Sometimes they’ll have a suit or jacket made to have subtle textural stuff in the weave that communicates the same info the sweater would — we see Felix Faust in one of these at one point. Alternately, for when it’s too hot out for a sweater etc., you can communicate the same using a coded knot bracelet. A lot of the communication things, including strat and Hive, have bracelet options for when you’re dressed differently, or at the swimming pool.

Masons

Masons

Factitious: How many Masons are there? From TLTL p.153: “Cornel MASON is the unquestioned master of more than three billion voluntary subjects…” But from TWTB p.251: “…my Empire, two billion people of the ten…”

Ada: Ah, good spotting on that contradiction! There are 3.1 billion Masons, but in 2454 it just recently crossed the 3 billion mark, so people are used to it being in the high 2 billions. On p. 251, Cornel MASON is being modest, reflexively using the old number rather than acknowledging the change.

Aretti: The Masons’ Roman theme seems to be very Western Roman Empire in everything they do. With that in mind, why is it that the title for children of the current Emperor, Porphyrogenne, is not Latin but rather Greek, and refers to a naming custom that existed in the Eastern Roman Empire and not the Western? Is this just a solitary exception, or do the Masons also draw from the imagery and symbolism of the Eastern Empire in other places? (And if the latter, are there other polities that have identified themselves with Rome that they draw on, or would Muscovy/the Ottomans/the Holy Roman Empire be bridges too far?)

Ada: Good spotting! There are some tiny byzantine things here and there with the Masons, and Egyptian too (Alexandria, the ziggurats and lighthouse in the Masonic capital), but Western Rome has indeed won out in the rhetoric. This is partly since Western Rome is more dominant in our cultural imagination now. It’s also because Byzantium is so deeply intertwined with Christianity, and the world of Terra Ignota is so hyper-afraid of Christianity, more so than of things like ancient Greek religion which isn’t considered dangerous the way the faiths that caused the Church War are. So there are small Byzantine and Ottoman edges to the Masonic empire, but they’re very subtle and usually unspoken. One of the biggest nods in that direction, though, is that most of the major Masons we see are ancestrally Middle Eastern. Mycroft doesn’t mention it much (because the vein of Greek nationalism in Mycroft’s upbringing makes him uncomfortable with Turkey and the Middle East) but if you look carefully at the descriptions when they’re introduced, Martin is described as “Persian” and Cornel MASON is also signaled as Middle Eastern in descent. So while the Masons are very international and very mixed in race, there is a concentration of the Eastern Mediterranean in there among the rest.

Aretti: This is extremely surprising, given that Saladin is the name of a famous Middle-Eastern sultan! I had been working from the assumption that the “Greek” ethno-strat had kind of Megali Idea-d and picked up portions of Anatolia to explain Saladin, but if that’s not the case, then his origin is substantially more confusing.

Ada: Yes, Mycroft has a very complicated love-and-awe-and-fear weirdness about Turkey and the Middle East. I don’t bring it to the fore very often because even Mycroft is uncomfortable with it. Remember that part of what Mycroft loves about Saladin is his strangeness and fearsomeness.

Brillists

Brillists

makoConstruct: Set-sets and the brillists: Imagine that there were a society built by and for cartesian set-sets, and it developed its own ten number profiling system, each variable having high predictive power over interpersonal dynamics cartesian set-sets care about. Now say we inserted a neurotypical person raised naturally in one of the major hives into this cartesian society. The cartesians’ profiling system would assign them an extreme, abnormal profile. The cartesian set-sets would find it very difficult to ‘restore’ this person’s profile to their society’s normal. They’d find it hard to change it much at all without extensive, painful therapy. Their profiling system would inevitably be attuned to the dynamics of their society- none of which could the visitor participate in, however brilliant they may have been in their birth society- and it would mostly ignore others. The cartesians, seeing this, might say to the Brillists, “No, YOU are set-sets!” (It would be facetious, because no cartesian set-set would take a profiling system that confined itself to a mere 10 variables seriously, but they would have a right ot say that and the Brillists would get harshly burned.) Has this test transpired, or has the thought experiment been posed? How did the Brillists respond to it? It seems to me that the Brillists’ theory is sort of inevitably thoroughly laced with status-quoist prejudice, designed only to do good in our cognitive domain, it finds it can’t function in another. Instead of humility, the Brillists stomp their feet and try to argue that those other worlds are degenerate cases, that they’re barren of human value, and who would want to understand them properly anyway. Am I being arrogant, judging them so? What would the Headmaster say to me?

Ada: I’m not going to tip my hand about this sort of thing since much is still to come in book 4, but this is a great direction to be thinking in terms of the Brillists.

Utopians

MakoConstruct: If a culture like the Utopians reached critical mass, I don’t think it would ever stop eating. It would infect us all with its akrasia-guilt, its power and its glamour, and its hope. Once we put on their visors, even just for a day, we would be snared. Whatever system they use to coordinate, it would never let us go. We would come to crave approval that only the Utopian process could provide, we would aspire only to Utopian virtues, we would buy deeply into the ideology of consequentialism, growth, perfectionism, and we would inevitably come to blame outsiders for the duration of Mortality’s reign, we might call anyone not a voker a “deathist” for being so abominably lazy while people are still dying, while humanity is still at risk. Having seen how many of your readers would have been pulled beyond their event horizon, do you still believe that the Utopians would be so much smaller than the other hives? Have you surveyed the general population, outside of your readership, and found that they really are that bad?

Ada: This question reminds me of the section in Freud’s “Civilization and its Discontents” where he talks about the different paths to happiness that people have tried throughout history, listing the ambition to advance human progress coequally with love, art, religion, and vegging out on cocaine as paths people have tried to lead to happiness. I think Freud is right that there are real paths to happiness down all these paths, and that the progress path is not one of the most satisfying because of the sacrifices it requires, (1) hours of toil, and (2) recognizing that the golden age you work for will be enjoyed by your descendants, not yourself. So I think many people would be excited by it, but also that many others would be intimidated by it, and drawn by other paths, such as the Humanist excitement about developing personal excellence, or the Cousins’ drive to help the present rather than driving toward a distant future. Thus I think the Utopians are numerous but not a majority. I think among my readers the majority do prefer Utopia but science fiction readers are a very specific sample, and even among us there are those who have read the Oath and felt it asked too much, and others who have found other Hives — Cousins, Brillists — more appealing. Because really all these Hives have powerful philosophies worthy of respect. The Utopian is the most powerful in some senses, with its mission to disarm death and touch the stars, but the most frightening in others, a potent mix.

MakoConstruct: Are the Utopians controlling their U-Beasts telepathically? The U-beasts’ sensitivity and synchronicity could suggest nothing else. How spectacular the U-beasts are, and the fact that the puppeteers clothe themselves in nowheres as if to say, “ignore the human. Keep your eyes on the puppet”, it makes me wonder if many utopians have come to project their identity into their U-beasts. I think if I could see and interact with the world through the body of a flying dragon I might well like to forget my human body, leave it behind, fit it with an exoskeleton that would walk it for me, let it trail along after me.

Ada: U-beast interface is indeed deeply mysterious, intentionally on the Utopians’ part.

MakoConstruct: Are the Utopians angry like I am angry? Do they quietly curse us every time we waste a day on entertainment or recreational drugs? Are they bitter, jealous of the power granted to those who sacrifice pieces of the future for temporary dominance in the present?

Ada: Angry about some things, yes. Not wasting days on entertainment or even on recreational drugs: the human animal needs rest and play to regenerate and stimulate the brain, so board games and mind-stimulating TV and all that is not only good but mandatory. But it does anger them (and many of us) when a big social policy stifles progress, when schools are throttled from spreading knowledge to the next generation, and when resources are wasted. An evening playing board games is an evening spent honing a mind that will reach for the stars — an evening filling out paperwork is a tragic victory for Entropy.

The Hiveless

The Hiveless

Fthagnar: We see about the Blacklaws and their merry lives in the latest book — how they love and thrive in the inconvenience of it, but how inconvenient is Hivelessness for the Greylaws and Whitelaws?

Ada: Graylaw isn’t really inconvenient at all, it’s very simple and ubiquitous and no one dislikes you, whereas some of the Hives sort of dislikes certain other Hives. Whitelaws I’m looking forward to showing another glimpse of in book 2, but Whitelaws tend to get lumped in with Cousins somewhat, though they’re actually very different. Cousin law focuses on mandating things that are good for the collective, things like requiring vaccinations or requiring educational stages that tend toward the broad social good. Whitelaw is much more about personal strictness, forbidding yourself from doing things in order to encourage the formation of strict moral character. So, for example, paid sex is illegal for both, but Carlyle could effortlessly get an exemption to go into a brothel to help someone else, but a Whitelaw absolutely couldn’t.

Bash’es

Bash’es

Praecipitantur: I’m curious about bash’ romances. I think Martin refers to the Saneer-Weeksbooth bash’ as “Open”, presumably meaning people date outside of it. What other implications does that carry? Are there other kinds of classifications for how bash’ handle romance? And, related–Is it considered taboo for ba’sibs to sleep together?

Ada: Yes, an “open” bash’ means at least one person dates outside, as opposed to a “closed” bash’ where no one is interested in further external relationships. Within a bash’, some bash’es have only two-person couples, while others involve polyamory, but people don’t tend to discuss that much because it’s considered to be prying into other people’s lives intrusively. Romance between ba’sibs (i.e. people with the same birth bash’) is common and acceptable, so long as it isn’t actual blood-incest. There is some Hive variance here, and the more permissive Hives (Humanists, Mitsubishi) have more comfort with ba’sib relationships and romances among cousins etc. than more cautious Hives like the Cousins. The Brillists have complicated and confusing guidelines about bash’-romance structures which make sense only to them.

Injygo: So blood relations are still important, even though the bash’ has replaced the traditional family. Is that also why the dynasty of Spain is only passed down through male heirs?

Ada: Yes. Remember that the isolated nuclear family we think of as “traditional” is itself, historically speaking, very young, predated by greater focus on extended families, and multi-family cohabitation in which a higher status family and lower status families in a patron/client or master/servant relationship formed the basis of the household. The world of Terra Ignota is yet another transformation in which the household is different, but some of the ideas about lineage and blood are the same.

RERoberson: I’m also super curious about the whole Bash structure, including how they are formed.

Ada: Bash-formation is expected to happen in the transition from youth to adulthood, when young people are at a Campus. A Campus isn’t quite a university, it’s an area with common spaces, dorms, and several different schools, some of which might be universities or colleges, others technical training spaces that teach you carpentry, programming, medicine, plumbing, etc. Different campuses have different focuses while having broad opportunities, so Romanova’s campus has lots of political opportunities, Lisbon’s has lots of marine opportunities from research to surfing, etc. People choose a Campus for its strengths and attend but might be studying things even more disparate than the disparate things at current colleges and universities, and you usually stay at a campus more than 4 years, since you’re doing technical training as well as undergrad-type things. There young people mix and mingle and meet each other and live together in dorms and form friend groups, and eventually come together into bash’es.

Some bash’es are hereditary, some new. In a hereditary bash’ like the Saneer-Weeksbooth bash, some of the children will go together to the same Campus and seek out just a few friends or romantic partners who would like to join their bash’, figures like Sidney Koons, or Martin Guildbreaker’s spouse Xiaolu. But the majority of bash’es form newly from the friend groups that develp at a Campus.

Dragonbeartdtiger: One of my favorite parts of your utopian/dystopian future vision is the bash’ system. In TLTL, it’s mentioned that bash’es were developed by Regan Makoto Cullen, but sometime after the flying cars and Hive systems were put in place. Were there proto-bash’es already existing, and Cullen just codified/formalized/promoted them, or did the bash’ system have to be rolled out officially over the course of a generation after the initial success? Are there still alternative household structures in the world?

Ada: There are alternative structures, mainly in Reservations where lots of other ways of living still thrive. The bash’ system was developed from observing groups of adults who cohabitated in productive communes, which has been a phenomenon for centuries and is today, but it was Cullen (Brill’s apprentice) who described them formally, argued that they were better for society, and whose huge influence popularized them and made them become ubiquitous within a generation.

Briefly: live right now is the Chicon Auction to raise money for this summer’s Chicago Worldcon, and they have some great Terra Ignota stuff including signed books and a special 2454 Antarctic Olympics Hoodie I made for Terra Ignota fun. You can bid online!

Briefly: live right now is the Chicon Auction to raise money for this summer’s Chicago Worldcon, and they have some great Terra Ignota stuff including signed books and a special 2454 Antarctic Olympics Hoodie I made for Terra Ignota fun. You can bid online!

Q: Why Don’t You Describe the Flying Cars?

Q: Why Don’t You Describe the Flying Cars? To give a real example, I contacted an awesome ant expert, Sanja Hakala, and discussed with her what ant species would make sense to be the Mars ants, given the locations of the space elevators, and how the resources for Mars were harvested and packaged, and the types of engineering they would need to navigate, and different likely ant migrations over future centuries, and with much debate we settled on Paratrechina longicornis as the most likely and appropriate ant species. Sure enough, the very next beta reader I had (a scientist but not a biologist) commented “Paratrechina longicornis! Really! What a boring choice, couldn’t you have bothered to do some real ant research?” A similar thing happened in book 4 with one particular bit of technology (intentionally being vague here) where I was working with 2 experts in that kind of tech and asked them, “So, it might seem they could achieve the goal by doing X, do I need to make clear in the book why they can’t do X?” Both experts answered, “No, it’s super obvious X wouldn’t work, X would fail because ABC, don’t bother to bring up X, anyone who knows anything will realize it’s obviously not an option.” Sure enough, beta reader’s response: “I spent the whole book thinking ‘why don’t they just do X! Obviously X would solve everything!” So I went back in and specified why they couldn’t do X.

To give a real example, I contacted an awesome ant expert, Sanja Hakala, and discussed with her what ant species would make sense to be the Mars ants, given the locations of the space elevators, and how the resources for Mars were harvested and packaged, and the types of engineering they would need to navigate, and different likely ant migrations over future centuries, and with much debate we settled on Paratrechina longicornis as the most likely and appropriate ant species. Sure enough, the very next beta reader I had (a scientist but not a biologist) commented “Paratrechina longicornis! Really! What a boring choice, couldn’t you have bothered to do some real ant research?” A similar thing happened in book 4 with one particular bit of technology (intentionally being vague here) where I was working with 2 experts in that kind of tech and asked them, “So, it might seem they could achieve the goal by doing X, do I need to make clear in the book why they can’t do X?” Both experts answered, “No, it’s super obvious X wouldn’t work, X would fail because ABC, don’t bother to bring up X, anyone who knows anything will realize it’s obviously not an option.” Sure enough, beta reader’s response: “I spent the whole book thinking ‘why don’t they just do X! Obviously X would solve everything!” So I went back in and specified why they couldn’t do X. Q: How much time do you spend planning?

Q: How much time do you spend planning? Q: Is there going to be a movie or TV series? Could there be?

Q: Is there going to be a movie or TV series? Could there be?

Between Utopia and Dystopia:

Between Utopia and Dystopia:

Hello, friends! Quick post today to say three things:

Hello, friends! Quick post today to say three things: Injygo: In Terra Ignota, it seems that the Great Men and Women dictate a lot of the course of history. The events that are the responsibility of collectives or of nonhuman forces seem to be minimized or put aside. Mycroft praises the nobility and exceptional nature of the Great Men characters, and seems to dislike the concept of popular revolution. Is this point of view Mycroft’s doing or yours? Do you think that history is driven by individual Great People?

Injygo: In Terra Ignota, it seems that the Great Men and Women dictate a lot of the course of history. The events that are the responsibility of collectives or of nonhuman forces seem to be minimized or put aside. Mycroft praises the nobility and exceptional nature of the Great Men characters, and seems to dislike the concept of popular revolution. Is this point of view Mycroft’s doing or yours? Do you think that history is driven by individual Great People? Infovorematt: What are your thoughts on opening up contemporary Olympic Games to include things like tennis, pole-dancing, skateboarding, surfing, etc?

Infovorematt: What are your thoughts on opening up contemporary Olympic Games to include things like tennis, pole-dancing, skateboarding, surfing, etc? Delduthling: Are there any actors who would be ideal fantasy-casting for Mycroft, JEDD Mason, Sniper, or any of the other major characters? I honestly can’t really envision what an adaptation would even be like (or whether it could possibly work), but it’s fun to speculate.

Delduthling: Are there any actors who would be ideal fantasy-casting for Mycroft, JEDD Mason, Sniper, or any of the other major characters? I honestly can’t really envision what an adaptation would even be like (or whether it could possibly work), but it’s fun to speculate. Infovorematt:

Infovorematt:  Wisegreen: Am I wrong in seeing a lot of Machiavelli in Terra Ignota? Despite Enlightment figures and Hobbes being sort of “philosophical figureheads” in the books, a lot of what the characters do or don’t, specially OS and Hive Leaders, also look & feel like exploring how far powerful figures would go for the world they believe is the better one…

Wisegreen: Am I wrong in seeing a lot of Machiavelli in Terra Ignota? Despite Enlightment figures and Hobbes being sort of “philosophical figureheads” in the books, a lot of what the characters do or don’t, specially OS and Hive Leaders, also look & feel like exploring how far powerful figures would go for the world they believe is the better one… AREalRedWagon: JEDD Mason’s upbringing reminds me a lot of the education of the english philosopher John Stuart Mill. Both of them were raised to speak several languages and with the intent to foster some sort of society changing genius. Is this a coincidence or are the parallels intentional?

AREalRedWagon: JEDD Mason’s upbringing reminds me a lot of the education of the english philosopher John Stuart Mill. Both of them were raised to speak several languages and with the intent to foster some sort of society changing genius. Is this a coincidence or are the parallels intentional? Ada: And best for last, food…

Ada: And best for last, food… Partoffuturehivemind: I’d like to know about translations of Terra Ignota into other languages. What translations are planned? It seems particularly challenging to translate, doesn’t it?

Partoffuturehivemind: I’d like to know about translations of Terra Ignota into other languages. What translations are planned? It seems particularly challenging to translate, doesn’t it? Injygo: The Utopian Hive is your love letter to the sff fandom of today. Is the Utopian jargon related to or inspired by in-jokes you have with your friends today? Could you tell us more details of Utopian speech and customs?

Injygo: The Utopian Hive is your love letter to the sff fandom of today. Is the Utopian jargon related to or inspired by in-jokes you have with your friends today? Could you tell us more details of Utopian speech and customs? Ada: I speak French, read Latin, read a little German and ancient Greek (though not modern Greek), and understand spoken Japanese a bit and have studied Japanese linguistics a lot but can’t read it. I don’t speak Spanish, so for that one I have to ask for help from friends, and I often do for German or Japanese too, to make sure I have the nuances right. When I’m writing Mycroft’s narration I sometimes intentionally flip back and forth between iambic meter (comfortable in English) and more dactyllic meter which is comfortable in Greek, to suggest when he’s thinking in which language. But the most language work I do is writing J.E.D.D. Mason’s dialog, since there I try to think through how He’d structure the sentence in all his languages before rendering the English but making it awkward in just the right way. It means it sometimes takes me a whole day to do a couple sentences of his dialog, but it’s worth-it!

Ada: I speak French, read Latin, read a little German and ancient Greek (though not modern Greek), and understand spoken Japanese a bit and have studied Japanese linguistics a lot but can’t read it. I don’t speak Spanish, so for that one I have to ask for help from friends, and I often do for German or Japanese too, to make sure I have the nuances right. When I’m writing Mycroft’s narration I sometimes intentionally flip back and forth between iambic meter (comfortable in English) and more dactyllic meter which is comfortable in Greek, to suggest when he’s thinking in which language. But the most language work I do is writing J.E.D.D. Mason’s dialog, since there I try to think through how He’d structure the sentence in all his languages before rendering the English but making it awkward in just the right way. It means it sometimes takes me a whole day to do a couple sentences of his dialog, but it’s worth-it! Haverholm: Do you listen to music while working on your books? And do you use music actively, choosing it depending on what you’re writing (achademic or fiction) or what mood you need for a specific passage?

Haverholm: Do you listen to music while working on your books? And do you use music actively, choosing it depending on what you’re writing (achademic or fiction) or what mood you need for a specific passage?

So does taking lots of breaks to rest and mentally refresh by watching anime or playing Pandemic Legacy with friends). The history work absolutely transformed how I think about the change and development of worlds over time and is a huge part of how I world build, the questions I ask about how institutions got to be the way they would be. I’m so incredibly fortunate to be at a university where colleagues are supportive of my fiction and don’t see it as taking time away from my other work.

So does taking lots of breaks to rest and mentally refresh by watching anime or playing Pandemic Legacy with friends). The history work absolutely transformed how I think about the change and development of worlds over time and is a huge part of how I world build, the questions I ask about how institutions got to be the way they would be. I’m so incredibly fortunate to be at a university where colleagues are supportive of my fiction and don’t see it as taking time away from my other work. Injygo: You’re the Ur-Fan, the Alpha Nerd, filker, historian, novelist, and sff fan. Can it be that you, like us mere mortals, have been frustrated or demotivated? How have you managed to become as cool as you are, and do you have advice for aspiring Alpha Nerds?

Injygo: You’re the Ur-Fan, the Alpha Nerd, filker, historian, novelist, and sff fan. Can it be that you, like us mere mortals, have been frustrated or demotivated? How have you managed to become as cool as you are, and do you have advice for aspiring Alpha Nerds? On 11th January 2018, Ada did an “Ask Me Anything” on Reddit. I’m preserving the most interesting parts of it here. In this post, questions about reading and writing.

On 11th January 2018, Ada did an “Ask Me Anything” on Reddit. I’m preserving the most interesting parts of it here. In this post, questions about reading and writing. My academic writing also definitely helped. Academic writing often has strict length limits, which require me to communicate complicated ideas in limited words, and forced me to learn the art of concision. The Terra Ignota books are pretty long, so most people wouldn’t associate them with concision, but I do think a lot about being concise in every line and paragraph, since the more information you pack into fewer words the more powerful prose becomes. That doesn’t mean I don’t take plenty of time off for little touches, descriptions, Mycroft tangents etc., but when I do so it’s because I’ve thought hard about the content I’m trying to convey there, and determined that it’s valuable, not just for that sentence, but for the mood, the character development, the reader’s emotional arc. Whether it’s a “she sighed” or a description of the glittering water outside a harbor, I really have read over every line carefully to make sure every word matters. Learning to do that helps so much.

My academic writing also definitely helped. Academic writing often has strict length limits, which require me to communicate complicated ideas in limited words, and forced me to learn the art of concision. The Terra Ignota books are pretty long, so most people wouldn’t associate them with concision, but I do think a lot about being concise in every line and paragraph, since the more information you pack into fewer words the more powerful prose becomes. That doesn’t mean I don’t take plenty of time off for little touches, descriptions, Mycroft tangents etc., but when I do so it’s because I’ve thought hard about the content I’m trying to convey there, and determined that it’s valuable, not just for that sentence, but for the mood, the character development, the reader’s emotional arc. Whether it’s a “she sighed” or a description of the glittering water outside a harbor, I really have read over every line carefully to make sure every word matters. Learning to do that helps so much. Book Recs

Book Recs

I spoke recently with a couple of reps from Oxford and Cambridge universities who work for the programs designed to offer scholarships to underprivelaged students, to help kids raised in poverty have a shot at being anything the want to be. They told me their biggest problem is lack of applicants, that young people in that situation don’t apply. Their worlds are full of messages that telling them that all the doors are already closed, that there’s no path forward, no way out. As one rep put it “The level of aspiration is appalling.” So if we can combat those messages, the messages that kill aspiration, I think that can unlock so many paths forward.

I spoke recently with a couple of reps from Oxford and Cambridge universities who work for the programs designed to offer scholarships to underprivelaged students, to help kids raised in poverty have a shot at being anything the want to be. They told me their biggest problem is lack of applicants, that young people in that situation don’t apply. Their worlds are full of messages that telling them that all the doors are already closed, that there’s no path forward, no way out. As one rep put it “The level of aspiration is appalling.” So if we can combat those messages, the messages that kill aspiration, I think that can unlock so many paths forward. “When you were undergrads you wanted to be a novelist and she wanted to be a vet and you both just did it!” And it’s true, we did, out of so many people who want to be a XXX when they grow up, we really did it. Because we kept that aspiration. And because those around us took that aspiration seriously, and when we told teachers and friends and parents, I want to be an XXX when I grow up, they didn’t say we couldn’t, but they also didn’t just blithely say “Great, go for it!” They helped us plan. They helped us see the steps. You want to be a writer? Okay, you need to do writing exercises, and give hours of training this. You want to be a vet? Okay, you need to take these classes, and look into these schools, and take these steps. You want to be a Renaissance historian? Okay, you need Greek so you need to transfer to a school that has it even though you really like the school you’re at. That’s what kept the door open for me. I think that’s the key, that we need to turn encouragement into a path with concrete steps, whether it’s a path we make for ourselves by looking into what we want, what we need to do to get there, and making a plan, or whether its a path we help make for others. Because all doors are open when we’re little, but as we grow up they close. That’s hard to understand. They close more and faster for some people than others, depending on poverty, race, gender etc., but for everybody some doors stay open and some close. I don’t think we’re very good at teaching young people to understand that. When I was seventeen advisers told me that, if I wanted to be the kind of historian I wanted to be, I had to make a hard choice, leave my college, give up my friend group, to get the Latin and Greek and training I needed to get into a grad school. And because I knew that was a step on the path, I did it. And it hurt, but I’m so glad. And every year I see several dozen applications from students who want to become historians who can’t because they don’t have the languages and background they need to do it well, they didn’t take the right steps at the right time. That door is closed to them. That’s something no one tells you when you’re ten and you want to be an XXX when you grow up. Sometimes people say “Go for it!” and sometimes people say “You’ll never be an XXX, you should be a computer science major so you have a secure job.” But very rarely do people say “That door is open, but it will close if you aren’t careful, so let’s sit down together and work out the steps to get you there.” So I think we need to do that more.

“When you were undergrads you wanted to be a novelist and she wanted to be a vet and you both just did it!” And it’s true, we did, out of so many people who want to be a XXX when they grow up, we really did it. Because we kept that aspiration. And because those around us took that aspiration seriously, and when we told teachers and friends and parents, I want to be an XXX when I grow up, they didn’t say we couldn’t, but they also didn’t just blithely say “Great, go for it!” They helped us plan. They helped us see the steps. You want to be a writer? Okay, you need to do writing exercises, and give hours of training this. You want to be a vet? Okay, you need to take these classes, and look into these schools, and take these steps. You want to be a Renaissance historian? Okay, you need Greek so you need to transfer to a school that has it even though you really like the school you’re at. That’s what kept the door open for me. I think that’s the key, that we need to turn encouragement into a path with concrete steps, whether it’s a path we make for ourselves by looking into what we want, what we need to do to get there, and making a plan, or whether its a path we help make for others. Because all doors are open when we’re little, but as we grow up they close. That’s hard to understand. They close more and faster for some people than others, depending on poverty, race, gender etc., but for everybody some doors stay open and some close. I don’t think we’re very good at teaching young people to understand that. When I was seventeen advisers told me that, if I wanted to be the kind of historian I wanted to be, I had to make a hard choice, leave my college, give up my friend group, to get the Latin and Greek and training I needed to get into a grad school. And because I knew that was a step on the path, I did it. And it hurt, but I’m so glad. And every year I see several dozen applications from students who want to become historians who can’t because they don’t have the languages and background they need to do it well, they didn’t take the right steps at the right time. That door is closed to them. That’s something no one tells you when you’re ten and you want to be an XXX when you grow up. Sometimes people say “Go for it!” and sometimes people say “You’ll never be an XXX, you should be a computer science major so you have a secure job.” But very rarely do people say “That door is open, but it will close if you aren’t careful, so let’s sit down together and work out the steps to get you there.” So I think we need to do that more. This is mostly advice for how to treat others more than advice for one’s self, because the self is difficult, but no matter what path you’ve ended up on generally you have a few hours you can give to the stars, whether it’s through work or through hobby time, or just through encouraging people. And sometimes, as I say in my song “

This is mostly advice for how to treat others more than advice for one’s self, because the self is difficult, but no matter what path you’ve ended up on generally you have a few hours you can give to the stars, whether it’s through work or through hobby time, or just through encouraging people. And sometimes, as I say in my song “