What Color is Pluto? (guest post)

A week from today, the NASA New Horizons Spacecraft will perform its close flyby of Pluto, beaming back the first color images of our solar system’s last uncharted world (and finally telling the makers of the Celestial Buddies line what color they should make their long-awaited cuddly Pluto). In celebration of the occasion, I have solicited a guest post from my good friend Jonathan Sneed, an astrogeologist/ paleobiologist, currently working as a research technician with the Solar System and Exoplanet Habitability Group here at the University of Chicago. Jonathan studies rocks, and what rocks tell us about how planets and other astronomical bodies form and develop, especially when life gets in the mix. These are the skills we need to predict which planets and other space rocks might have life, or the chemicals necessary to support us as we launch out into the vast and black frontier. Jonathan’s essay offers predictions about what New Horizons might find when it makes its flyby next week, gives a taste of how much photos alone can teach us about the history and potential of Pluto, and offers a glimpse of how astrogeology lets us learn about the celestial stepping stones scattered around us.

A week from today, the NASA New Horizons Spacecraft will perform its close flyby of Pluto, beaming back the first color images of our solar system’s last uncharted world (and finally telling the makers of the Celestial Buddies line what color they should make their long-awaited cuddly Pluto). In celebration of the occasion, I have solicited a guest post from my good friend Jonathan Sneed, an astrogeologist/ paleobiologist, currently working as a research technician with the Solar System and Exoplanet Habitability Group here at the University of Chicago. Jonathan studies rocks, and what rocks tell us about how planets and other astronomical bodies form and develop, especially when life gets in the mix. These are the skills we need to predict which planets and other space rocks might have life, or the chemicals necessary to support us as we launch out into the vast and black frontier. Jonathan’s essay offers predictions about what New Horizons might find when it makes its flyby next week, gives a taste of how much photos alone can teach us about the history and potential of Pluto, and offers a glimpse of how astrogeology lets us learn about the celestial stepping stones scattered around us.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

So, Pluto.

When she’s talking about the history of skepticism, our host likes to talk about Pluto, and in particular about the argument that scientists had about it. Shall it be a planet? A dwarf planet? A planetoid? Megarock? Especially large ice cube? In her classroom, Pluto is the enemy of eudaimonia, a didactic example of the stress we experience when our perceptions shift and the maps are all rewritten. She discusses the ways that we use doubt to insulate ourselves against collisions between truth and belief, how the ancient Pyrrhonists found a refuge in uncertainty. It’s all rather grim.

Obviously, I can’t let her be the one to talk about the imminent New Horizons flyby.

It is, after all, a unique moment in human history! For most of us, most of the time, discovery is a kind of communication. You turn to page 57 and look at a full-page spread of the Krebs Cycle, or stop by a street performer on your way to the grocery store and hear real jazz for the first time, or open your RSS feed and read a quote by Sartre, and your world shifts under your feet just a bit. But moments like this are a reminder: there are things that nobody knows, and you have the ability to know them. If you’re willing to admit a little uncertainty, that is.

Over the next few weeks, a great many things will become known about a whole new world. I thought this might be a good opportunity to sketch out some of what you might look for, so that you can participate a little bit more actively in that moment, if you have a mind to do so. The New Horizons craft is outfitted almost entirely with cameras, imagers, and spectrometers of one sort or another, so we’ll have basically one thing to go on: what color is it?

Granted, some of those photons will be well outside the range of the human eye, so I’m using ‘color’ with a certain amount of poetic license. But at the end of the day, it’s a remarkably straightforward little device. We were curious about Pluto, so we looked at it. The atmosphere should be quite visible, and it’s more than thin enough for us to peer through that atmosphere to the solid surface beneath. From there, we’ll see not just the elements that make up pluto, but also the chemical arrangements that they’ve made for themselves and the large shapes and geological formations that have emerged. Are there mountains and valleys? Volcanoes? Some kind of erosional process that cycles and recycles the surface?

And these things, in turn, will tell us more than you might expect. Because we don’t just know what Pluto looks like now; we have a pretty good guess about where it started, and two points make a line.

Origins:

One of my favorite facts (up there with ‘birds are dinosaurs’) is that the number of mineral types in the universe is increasing at an exponential rate. For a geologist, every day is the most exciting day the universe has ever had! A while back, the first stars and the preposterous forces at work inside them, gave us the first heavy elements and the few mineral grains they can form drifting in interstellar space. Eventually, those first primitive grains clumped together to form rocks and then whole planets, with solid bits and fluid bits and change, and new minerals emerged from that dynamism. The kind of minerals that are only formed when water evaporates into an atmosphere and leaves a residue behind. The kind that are only formed when some kind of fancy-pants self-sustaining carbon-based chemical process decides to secrete a shell for itself. The kind that first come in to being when a state legislature settles on new safety standards for concrete. And so on, accelerating ever onwards.

(Actually, human-created objects don’t technically count as minerals, but this is an arbitrary semantic line. ‘Anthropocite’ is far too wonderful a word to not get used in a scientific journal eventually.)

What this means for Pluto is that, despite the huge variety of things that a (dwarf) planet(oid) might do, the starting ingredients have to be drawn from a set of things that can be cooked by a star and are willing to clump together in space. As to what it did with those things in the four and a half billion years since… well, that’s harder to guess. But here are some of the most important ingredients that might go into your Pluto recipe, drawn straight from the primordial dust itself:

Water ice. Ammonia. Silicates, with a variety of elements thrown in for flavor- potassium, phosphorous, a great many metals. Iron and sulfur compounds, usually bonded with oxygen or mixed in with the silicates. Carbon, doing its crazed carbon dance, probably already forming a few amino acids and alcohols as it falls into the gravity well. Carbon, being less creative, oxidized or in the form of methane. Hydrogen and helium, as much as you like, although those will run away from the world almost as soon as they arrive.

I’ve been careful to emphasize some of the ones that I think are going to be important, so this is isn’t comprehensive. But it’s a lot closer to comprehensive than you’d think. All in all, there are a little more than a hundred different molecules floating around between the stars, a shockingly finite list.

Even more conveniently, we have a category we can use. No, not ‘planet’, alas. The category I am thinking of is ‘Kuiper Object’. On Ex Urbe, categories are a deep and compelling subject in their own right, but for the time being I shall take a narrow and cowardly view. All I mean is that Pluto is quite similar to a lot of other things in the ways we have already measured, and so I wouldn’t be too surprised if it was also similar to those things when we measure new aspects of it.

Kuiper Objects are a fascinating bunch, named by the region just outside Neptune’s orbit. They’re quite icy (some would even float), and they come in a range of exciting colors for the discriminating consumer (gray is common, and red and black are, as always, favorites). There are many things we don’t know about Kuiper objects, but we’ve also had one tantalizing opportunity:

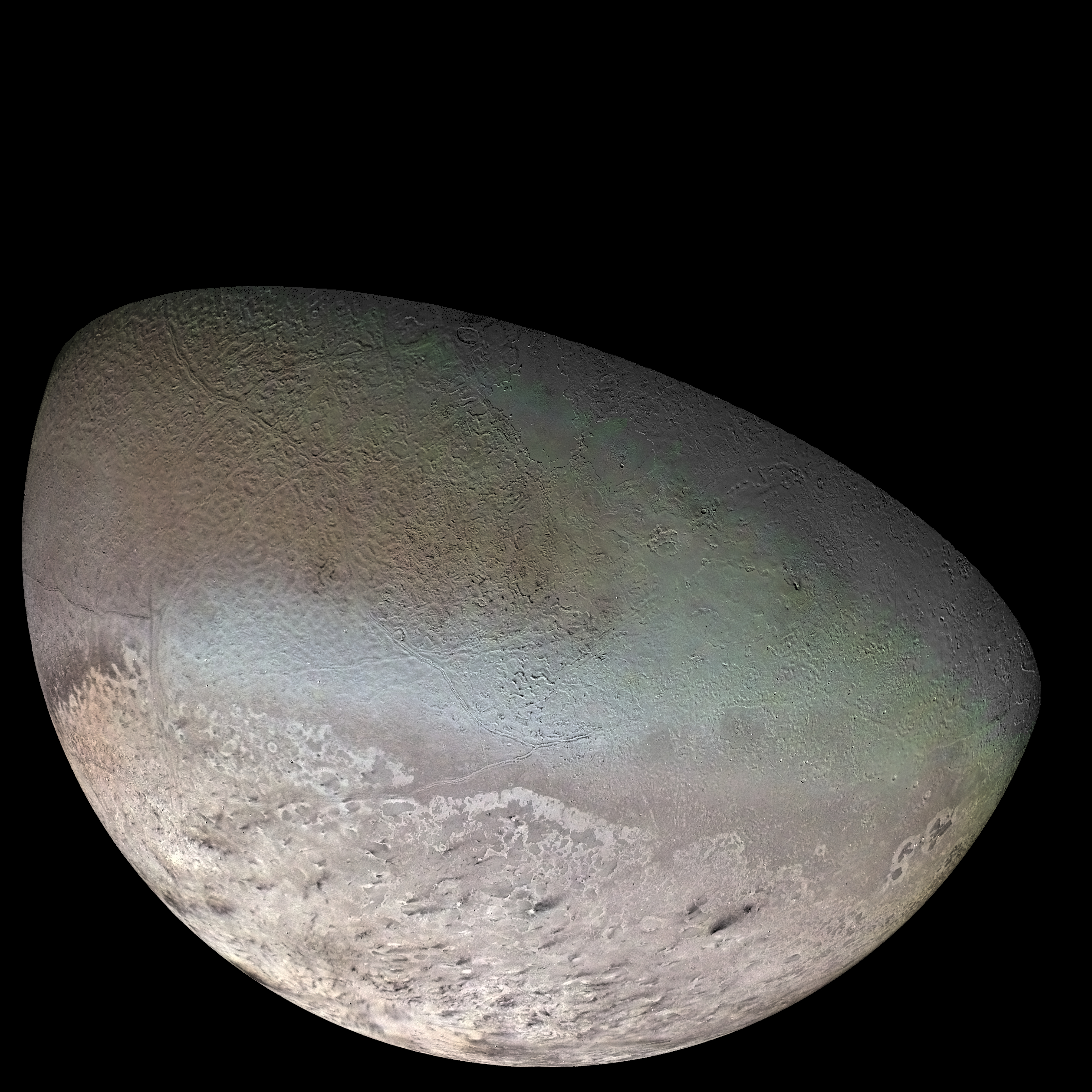

This is a picture of Triton, one of the moons of Neptune, given to us by interstellar traveler and Blind Willie Johnson fan Voyager II. Triton is quite icy, although it would not quite float in water. It comes in a range of exciting colors, primarily gray and red. And it’s going around Neptune in basically the wrong direction, which implies that it fell into Neptune’s gravity well a good deal after planetary formation. It also, for the record, has an atmosphere, surface composition, and density shockingly similar to that which we infer for Pluto. So, there’s that.

Motion:

A while back, I shared an office with a guy who wrote a thesis about how confusing Kuiper Objects are. He had written an efficient and cutting-edge program that would transform reasonable assumptions into arcane squiggles and crying graduate students. I learned a lot from that guy, especially about the perils of trying to predict the behavior of (dwarf) planet(oid)s given even very simple starting conditions. What happens when you make a very, very large pile of ice and silicates, and then wait for four and a half billion years? What do we expect to see when we take our picture of Pluto? Potentially, a lot of things.

But for any big pile of rocks, there are basically four ways to get the thing to move: sunlight, radiation, gravity, and chemistry. Actually, gravity and radiation make a nice twofer.

The idea is this: shuffle silicate rocks and water ice into a big ball. A lot of the heavier metals mixed in with your silicates are a bit radioactive, so they warm the ice around them into a kind of slush (same reason the Earth is a fluid once you go a few miles down). That’s just enough lubrication to let the heavy stuff fall to the bottom, and the lighter stuff rise to the top- and now we have some density gradients to work with, and maybe even some liquid(ish) water. Even more excitingly, everything in that ball that isn’t easily trapped in mineral form (the nitrogen compounds, the methane, and all those wonderful mad organic molecules) will tend to get squeezed out to the exterior surface, or near it. We call those ‘volatiles’, which is one of those charmingly literal phrases that scientists sometimes use. They explode, is what I’m saying.

Almost certainly, this is the process that first set Pluto in motion. But what happens then, especially on the surface? Once you squirt out all the gasses and form an atmosphere, and expose your wiggly mad carbon to sunlight, what does it do next? Well, here’s where the graduate students start crying, but let’s give it a shot. We’ll start with the most sensible and least speculative feature, giant ice volcanoes.

Ice volcanoes are a good sign of an active world, for the same reason that molten rock volcanoes are on Earth- they have to be refreshed by ongoing tectonic activity. As far as we know, they’re exactly the same kind of structure. At temperatures this low, ice is just another kind of rock, and it takes geological forces to warm that rock up to its melting point and expel it as magma. Except, the magma is water (plus a complicated mix of other volatiles like nitrogen)- so we call it ‘cryomagma’, a truly fabulous word if ever I saw one.

If we’re exceptionally lucky, we’ll see an active volcano during the flyby- on Triton, our closest analogue to Pluto, these eruptions can last for (Earth-) years, so it’s not an unreasonable hope. But even if we don’t, we should be able to find strong evidence that they did happen; look for dark smears in the calderas as frozen nitrogen ‘ash’ falls back to the surface.

Another really important thing to watch out for is the craters. Specifically, there not being any.

Here’s a puzzle for you: how do we date rocks on Mars? If you’re lucky enough to have a rover right there, you can run any number of exciting tests, but it’s a big planet and there aren’t that many rovers. Yet, we have guesses about the age of Olympus Mons and Hellas Planitia. How?

The answer is that Mars is fairly inert- enough so that the craters are more or less permanent fixtures. So if you know how often a meteorite is going to blow a hole in a given area, all you have to do is count the craters and then you have a pretty good measure of how long that surface has been exposed. ‘Pretty good’ means plus or minus 600,000,000 years, granted. But I think it’s a pretty cool trick anyway.

So if we make it to Pluto and it’s covered in craters like Earth’s moon or Mars, then that means Pluto has slowed down a lot in the last few billion years. If, on the other hand, it’s fairly crater-free, then something is busy removing those craters. That smells quite a bit like active tectonics. So: ice volcanoes, or craters, but not both- those tools could give us a pretty good idea of whether there is an active mantle in the subsurface, pushing the outer (nitrogen, methane, ice) crust around and otherwise being interesting.

Only, that mantle would be a fluid made of, among other things, water.

Chemistry:

As a species, we’ve gotten very good at looking, so even before New Horizons we knew a few things about the surface of Pluto. Broadly, it has the coloring we expect for a Kuiper Object: grey, black, and red, and is sharply mottled. But what, actually, do these colors mean?

I mentioned sunlight as one of the forces that must move Pluto. Granted, the sun lacks a certain degree of strength at that distance, but in combination with the rotation of the (dwarf) planet(oid), the sun is going to be the primary cause of temperature variations at the surface, far away from all that radioactive rock at the center. As the ice volcanoes have shown us, it’s not so much the absolute temperature that matters, as whether or not that temperature cycles around any interesting phase transitions. And as it happens, there are three (and only three, that I know of) materials in our original Pluto recipe that have an interesting phase transition at Pluto’s surface temperatures: carbon monoxide, methane, and nitrogen.

These can have seasonal rhythms, they can precipitate or frost, and are generally going to provide a lot of the bulk material for all the really interesting chemical reactions at the surface. If the ice of Pluto is as rock on Earth, then these are its water and air.

Nitrogen doesn’t help us with that coloration problem too much, but the other two? Those are interesting. Because the beating heart of both is a bit of carbon, and carbon is flexible enough to explain a great many things and a great many colors. This is the element that gives us black graphite and transparent diamonds, after all. When our carbon molecules are left outside for a few billion years of exposure, through years of those interesting phase transitions, something will change- the carbon will fry in the ultraviolet light. Very, very slowly, and it has to be peeled away from the hydrogen and oxygen first, but it will fry all the same. And as it happens, this can explain both the red and the black against a grey ice background.

These are not, of course, the only explanations for the colors that we see on the surface of Pluto. Red has a classic association with iron oxides (you and Mars are red for the same reason, as it happens), and there is a potential universe out there where the surface of Pluto is rusted. But the world is not very dense, and so this would require a great many odd things- not only that there be no mantle fluidity to pull dense minerals inward, but that some inverse process pulled it away, concentrating that metal on the outer circumference. I can’t think of what that might be. But nonetheless, it could be what reality gives us. The disadvantage of this theory is not that it is impossible, just that it requires a great many things to be true. And so I lean towards an explanation that doesn’t demand further concessions from reality, using only the processes that we already acknowledge on the parts that we started with.

Carbon and Water:

I have done a mean thing. I used cryovolcanics and an analogy to Triton as a way of suggesting that there might still be liquid (or at least slushy) water on Pluto. And then, I invoked a reasonably elegant explanation of Pluto’s mottled coloration to suggest that surface processes are driving chemistry of complex carbon molecules.

You are now thinking about aliens.

Or at least, I assume so. I would be. Not flying saucers or anything out of our drive-through horror shows. No, you’re considering the possibility of some simple microbe, maybe a Plutonian lichen of some sort, with subtle but radical implications for our role in the universe as living things. Then again, maybe not; I spend a lot of time thinking about aliens, so my calibration may be off. But if you were thinking about aliens, I apologize. There are not aliens on Pluto. Definitely not, certainly not. I am at least 95% sure, and even that is rounding down. Probably.

There’s a funny inverse to the eudaimonia of skepticism. If we remember that anything we believe might be false, then we can indeed let go of our beliefs with a certain grace. But if anything might be false, then just think of all the things that might be true! And there’s the danger. Before long, we look up and see the canals on Mars that we hope for, rather than the Vallis Marineris as it actually is.

Every planet and moon that we’ve investigated in this solar system has been utterly unique. These worlds are awesome, and frightening, and alien. Crystal cities on Venus would have been amazing, but they would have been amazing in a very human way- they would have been our fantasy, not an encounter with a genuinely new reality. And in the same way, whatever is really on Pluto, it’s going to be an experience that wasn’t bent to fit our expectations, a thing that nobody knows. It will be wonderful, even though it won’t be life.

Probably.

______________________________________________________________________________________

I hope you will join me in thanking Jonathan for this delightful contribution! -Ada