Spot the Saint: More Dominicani

Hello, all. Deadlines, page proofs, preparing for tenure, and an extra heavy autumn teaching load with classrooms full of enthusiastic-and-therefore-time-consuming students have continued to keep me too busy for another skepticism essay, but here for your enjoyment (and with some help from the excellent Jo Walton who’s wonderful at hunting down saint pictures for me) is a new addition to my Spot the Saint Series, on how to recognize saints in art (click here to start the series from the beginning).

Today: more Dominicans.

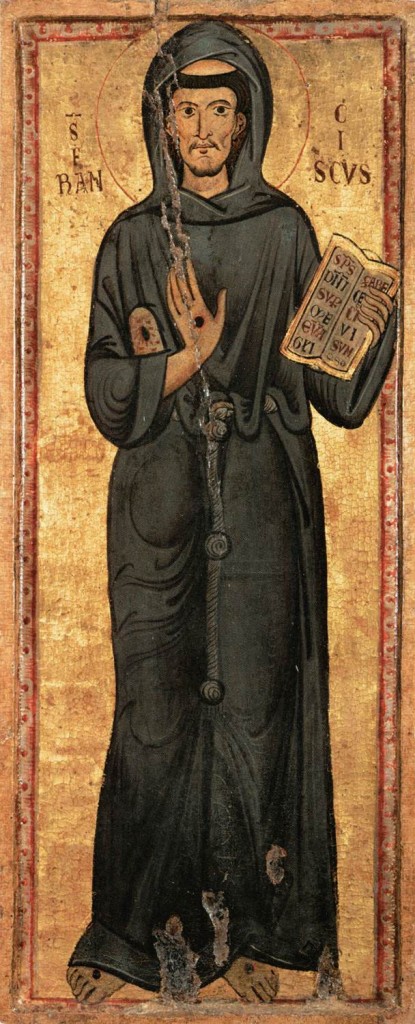

As we all recall, the key to recognizing Dominicans in art is that they look like penguins. (Black mantle over white robe – black wings, white belly.) Dominicans are generally scholar monks, dedicated to the idea that the best way to reach Heaven is through knowledge, reason and study. They are associated with Spain, through their founder Saint Dominic, and were particularly prominent at the University of Paris. For many years the primary theological adviser to the pope (called the Master of the Sacred Palace) was always a Dominican, and when the Roman Inquisition started kicking into high gear in response to the printing press and the Reformation, the Dominicans were in charge of it. If you are familiar with the Jesuits, the Dominicans did a lot of the things the Jesuits would start to do in later periods.

In addition to Dominic, Thomas Aquinas and Peter Martyr, there are three other Dominican saints who show up frequently in Renaissance art, or at least in Florentine art. They are St. Antoninus, St Catherine and Siena, and St Vincent Ferrer.

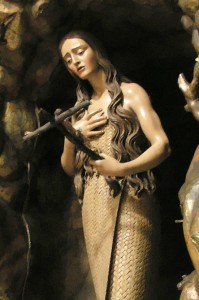

St. Catherine of Siena

- Common attributes: Nun in Dominican robes, crown of thorns, lily

- Occasional attributes: stigmata, book, model church, rose(s)

- Patron saint of: Nurses, the sick, women tempted by lust, people mocked for their faith

- Patron of places: Italy, Europe (yeah, she’s a big deal…)

- Feast days: April 29-30

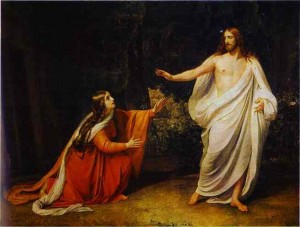

- Most often depicted: Looking otherworldly & contemplative, marrying Christ, giving alms to the poor

- Relics: body in Santa Maria sopra Miernva in Rome, head in Siena

Catherine of Siena (1347-1380) is one of the two patron saints of Italy, along with St Francis. In 1970 she was one of the first two woman ever to be named a Doctor of the Church (along with Saint Teresa of Ávila).

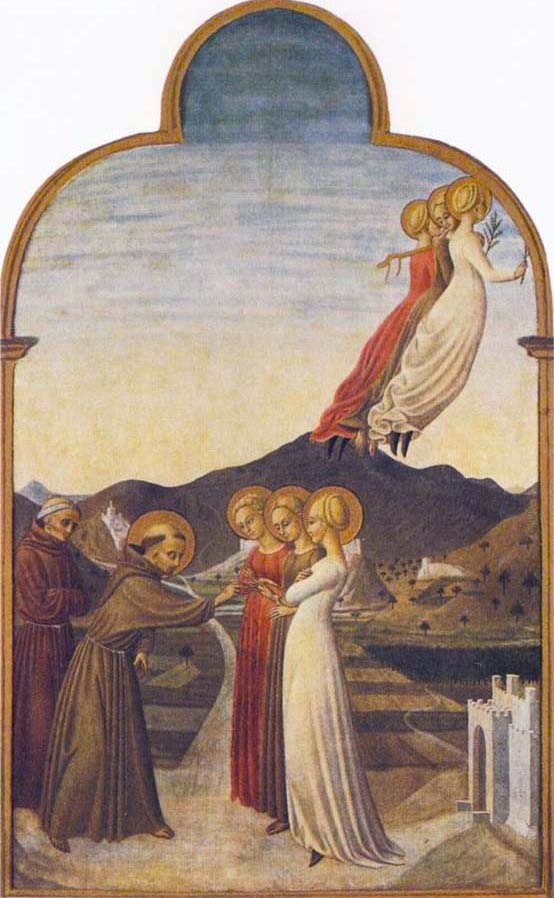

Catherine was born immediately before the Black Death, the twenty-third child in her family. It was a poor family, and she received no education, and did not learn to read until quite late. Growing, up she had every attribute of a classic un-learned female mystic. As a girl she had visions, and conversations with Christ, St Dominic, and the Virgin Mary. She refused to marry, but also refused to retreat into a cloistered life within a monastery, since she wanted to preach and travel, as male Dominicans did. At the age of twenty-one, she went through a mystic marriage with Christ, where he gave her his foreskin as a wedding ring — it was invisible to other people. Much like Francis of Assisi, she fasted almost constantly, and performed other extreme mortification of the flesh including drinking pus from the sick in hospitals. She also developed stigmata like Saint Francis, though some reports say they were invisible. Given how hard Catherine was on her body, it is no surprise that she only lived to be thirty-three.

Catherine was born immediately before the Black Death, the twenty-third child in her family. It was a poor family, and she received no education, and did not learn to read until quite late. Growing, up she had every attribute of a classic un-learned female mystic. As a girl she had visions, and conversations with Christ, St Dominic, and the Virgin Mary. She refused to marry, but also refused to retreat into a cloistered life within a monastery, since she wanted to preach and travel, as male Dominicans did. At the age of twenty-one, she went through a mystic marriage with Christ, where he gave her his foreskin as a wedding ring — it was invisible to other people. Much like Francis of Assisi, she fasted almost constantly, and performed other extreme mortification of the flesh including drinking pus from the sick in hospitals. She also developed stigmata like Saint Francis, though some reports say they were invisible. Given how hard Catherine was on her body, it is no surprise that she only lived to be thirty-three.

What made Catherine an ecclesiastical superstar, differentiating her from scores of similar female mystics who were popular in their day but remained only minor local figures, was that in the later part of her (not very long) life she began to transition from a mystic to a theologian. Mysticism was one of few paths to respect and authority that were open to women within Medieval Christianity. A religious vocation for a woman would traditionally have led to a cloistered life (as Saint Francis prescribed for Claire of Assisi) but Catherine rejected this. She chose instead to join the Dominican Tertiaries, an order of lay nuns created for widows who wanted to have a spiritual life while continuing to live with their families to care for children and family fortunes. Catherine was the first non-widow to join the order (over much protest), and thus granted a unique new status as a nun without a convent, and a spiritual woman without a place or superior to anchor her. This let Catherine wander widely to do good works and preach. Her mysticism and reports of visions, and her frequent transports into dramatic ecstasy, earned her great fame, so people crowded to see her wherever she went, even when her words began to sound less like mysticism and more like serious scholarly theology. Her ideas were very different and substantially more penetrable than the learned, Thomist, Aristotelian content of many sermons. She was taught to read by the Tertiaries when she became one, and the Dominicans assigned a scribe to follow her around and write down everything she said. At first this simply produced accounts of her ecstatic visions, but over time she began to dictate more polished and serious works, and letters to people in many corners of politics. She even served as Florence’s ambassador to the Avignon papacy for a time. When she turned thirty, she learned to write, and helped to edit and polish her corpus, which includes nearly four hundred letters, a dialogue, and some prayers. This constituted the first substantial body of theological writing by a woman of the Renaissance (though there had certainly been Medieval female theologians such as Hildegard of Bingen), and the first written theology ever by a woman from such a poor background who would not normally have had access to education.

What made Catherine an ecclesiastical superstar, differentiating her from scores of similar female mystics who were popular in their day but remained only minor local figures, was that in the later part of her (not very long) life she began to transition from a mystic to a theologian. Mysticism was one of few paths to respect and authority that were open to women within Medieval Christianity. A religious vocation for a woman would traditionally have led to a cloistered life (as Saint Francis prescribed for Claire of Assisi) but Catherine rejected this. She chose instead to join the Dominican Tertiaries, an order of lay nuns created for widows who wanted to have a spiritual life while continuing to live with their families to care for children and family fortunes. Catherine was the first non-widow to join the order (over much protest), and thus granted a unique new status as a nun without a convent, and a spiritual woman without a place or superior to anchor her. This let Catherine wander widely to do good works and preach. Her mysticism and reports of visions, and her frequent transports into dramatic ecstasy, earned her great fame, so people crowded to see her wherever she went, even when her words began to sound less like mysticism and more like serious scholarly theology. Her ideas were very different and substantially more penetrable than the learned, Thomist, Aristotelian content of many sermons. She was taught to read by the Tertiaries when she became one, and the Dominicans assigned a scribe to follow her around and write down everything she said. At first this simply produced accounts of her ecstatic visions, but over time she began to dictate more polished and serious works, and letters to people in many corners of politics. She even served as Florence’s ambassador to the Avignon papacy for a time. When she turned thirty, she learned to write, and helped to edit and polish her corpus, which includes nearly four hundred letters, a dialogue, and some prayers. This constituted the first substantial body of theological writing by a woman of the Renaissance (though there had certainly been Medieval female theologians such as Hildegard of Bingen), and the first written theology ever by a woman from such a poor background who would not normally have had access to education.

Before this starts to sound too progressive, Catherine of Siena never stopped being a traditional mystic, having visions, ecstasy etc., and it was absolutely because of her status as a mystic that everyone (the Dominicans, Florence, Rome) started to care about her. Mysticism was a traditional path which Catherine never left, though she did add something new to it, which women generally had not done before, through her preaching and written works. It is really in the posthumous reception of her work that the transition becomes more significant. Over the centuries since Catherine’s life, people in the Catholic Church and in the West in general have come to care more and more about education and especially education for women, and less and less about mysticism. Society’s taste in saints has changed, and as it changed the many dozens of female mystics came to fit it less and less, while Catherine-the-groundbreaking-theologian came to fit it more and more. Hence the expansion of her cult over the past centuries while many other saints’ cults have diminished, and her elevation to the prestigious positions of Patroness of Europe, Patroness of Italy alongside Francis whose life hers modeled so much, and in 1970 Doctor of the Church.

Catherine died in Rome at the age of thirty-three, after a stroke probably caused by what would now be called anorexia. Her body was immediately put on display in the Dominican headquarters church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, and began to be venerated there even though she would not be canonized for another 80 years.

This kind of sudden veneration of a non-canonized body was really not allowed, and happened a lot in more peripheral towns where Rome had little control, so the fact that it happened in Rome itself was quite remarkable.

Her head was stolen almost immediately, and smuggled back to Siena, where it was encased in a bronze bust, which was honored in a parade which Catherine’s (very tired) mother attended.

Catherine was canonized in 1461 by Pius II, who was himself from Siena, so he had strong personal reasons to encourage the veneration of this great celebrity who would bring honor and pilgrims to his hometown. He was also a scholar and theologian himself, so his enthusiasm for Catherine was certainly motivated by sincerity as well as hometown pride.

Siena’s excitement about Catherine is overwhelming to this day.

Siena’s excitement about Catherine is overwhelming to this day.

One time I was visiting Siena to see a manuscript, and got to chatting with the taxi driver, who told me I should visit Catherine’s head while I was in town. I told him I had just visited her body in Rome. He became very quiet for a moment, and then said very seriously, “The head is the important part.”

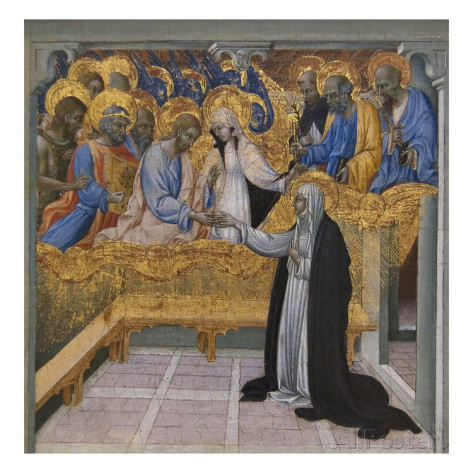

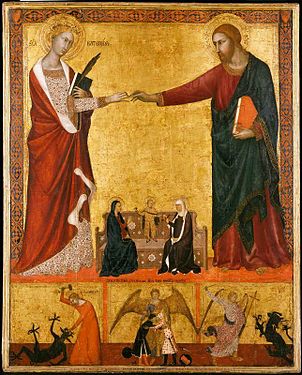

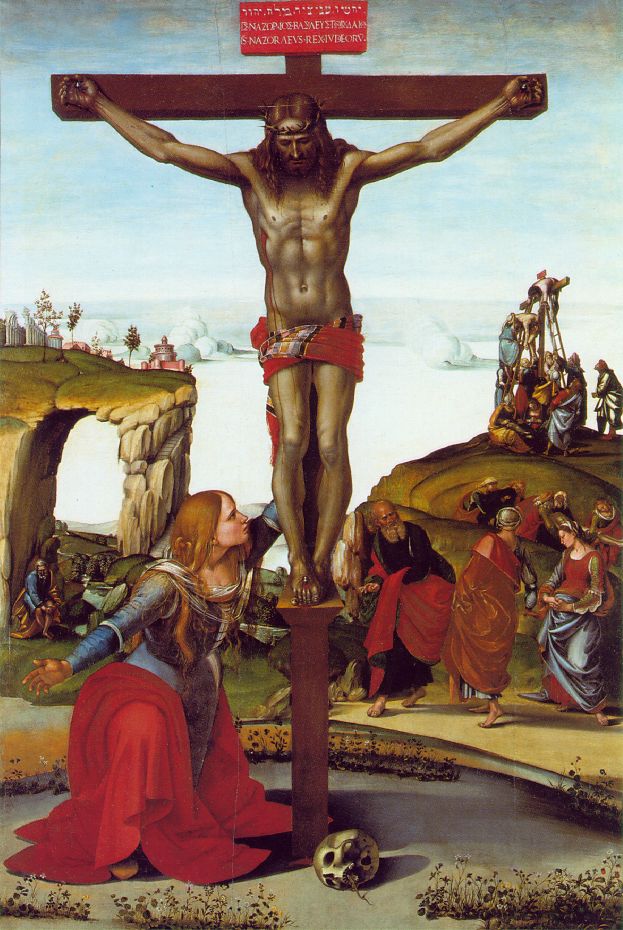

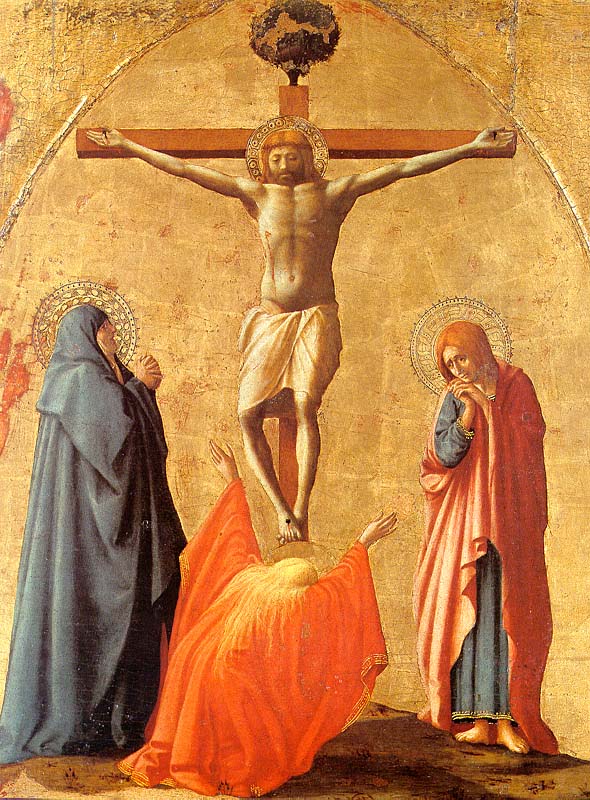

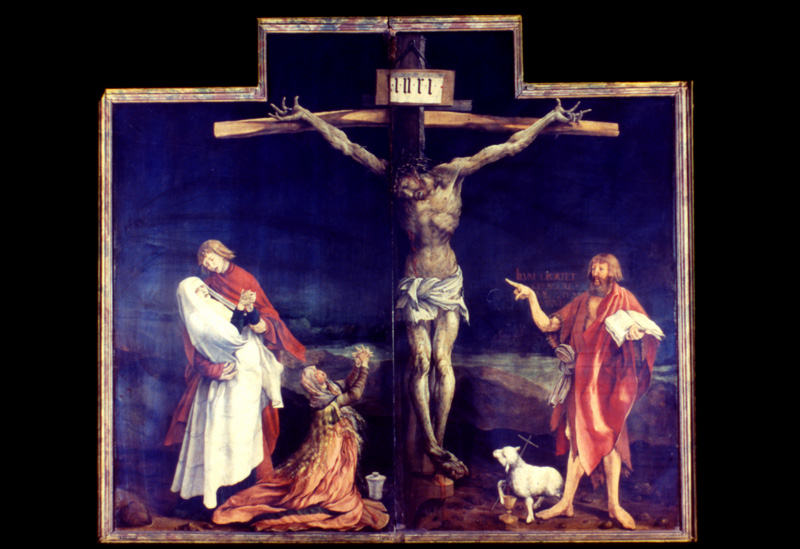

In art Catherine can most easily be spotted as a female Dominican, sometimes balancing a female Franciscan, who will be St Clare. (If there’s a female Benedictine, it’s usually St Scholastica.) She often has a lily, representing her chastity and connecting her to Saint Dominic who also holds one. In later art, 17th century and on, she pretty consistently has a crown of thorns. In some early art she was depicted with stigmata, but the Franciscans protested, and got the Church to rule that only Francis may be depicted with stigmata, so any images of Catherine with stigmata are technically heretical. Sometimes Catherine wears a starry headscarf (especially in paintings by Fra Angelico), which can lead her to be confused with the Virgin Mary. There are paintings of her visions, and of her mystical marriage. She is sometimes depicted holding a rose, reflecting a miracle that happened when her head was being smuggled out of Rome to Siena, and guards inspected the mysterious package as the thieves were leaving the gates of Rome, but when they looked in the bag they just saw a pile of roses instead of the head, so the head made it safely to Siena.

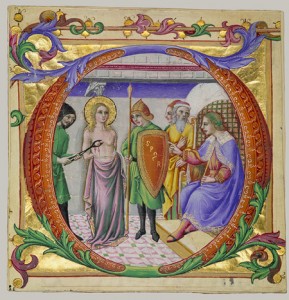

IMPORTANT: DO NOT confuse CATHERINE OF SIENA with CATHERINE OF ALEXANDRIA.

They have a lot in common, and are often depicted together, so the names can make it easy to mix them up. Both are virgin saints, and both had a mystic marriage with Christ, but Catherine of Alexandria is depicted having a mystic marriage with the INFANT Christ, while Catherine of Siena is usually depicted as marrying the ADULT Christ. In addition, Catherine of Alexandria has a wheel, a crown, a martyr’s palm, and Roman clothes, while Catherine of Siena has a nun’s habit, and a lily, and if she has a crown it’s thorns, rather than a queenly crown. Here they are together:

Though before you get too comfortable, they do sometimes reverse which Catherine marries the adult Christ and which marries the baby:

St. Antoninus of Florence

St. Antoninus of Florence

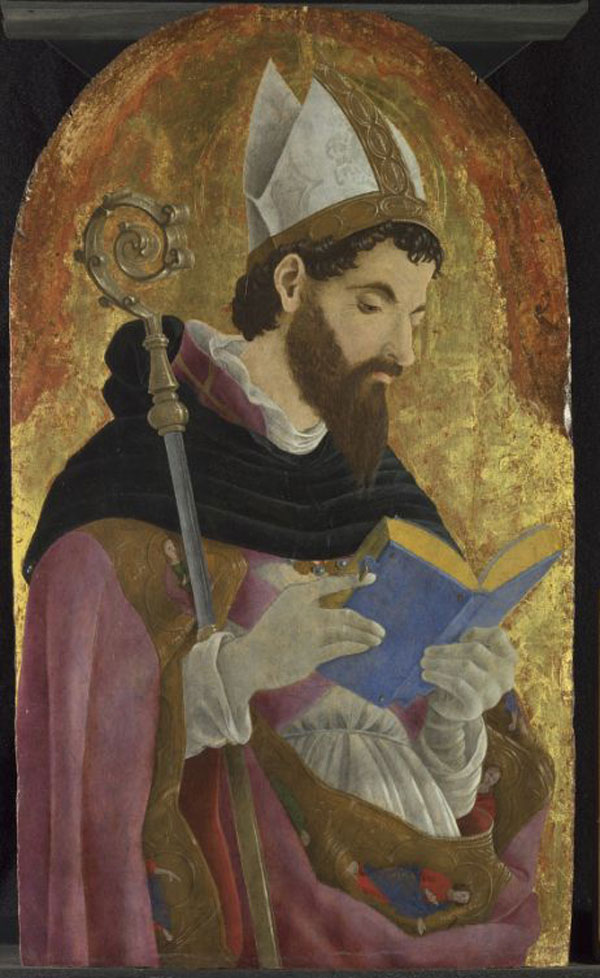

- Common attributes: Dominican robe with white T-shaped sash with crosses on it across his shoulders (indicating that he is a bishop)

- Occasional attributes: Bishop’s hat, bishop’s robes over Dominican habit

- Patron saint of: Florentine Dominicans

- Patron of places: The town of Moncalvo near Turin, + Florence

- Feast days: May 2nd and 10th

- Most often depicted: In Florence

- Relics: Florence, San Marco

St Antoninus (1389-1459) is Florence’s own saint, the first Florentine to actually be made a saint since Saint Zenobius (d. 417 AD) which is a long time for Florence to wait, while their neighbors kept accumulating more and more: Saints Francis & Claire of Assisi, Saint Peter Martyr of Verona, Saint Antony of Padua, Saint Dominic buried in Bologna, Saints Bernardino and Catherine of Siena, etc.

Antoninus was the son of a Florentine notary. In 1405 he became a Dominican and joined a monastery in the small hill town of Fiesole, just outside Florence. At that time, there was only one large Dominican monastery in Florence, the one attached to Santa Maria Novella (now by the train station). The Dominican brotherhood at Santa Maria Novella had been founded in 1221 to celebrate a peace settlement between the Guelphs & Ghibellines (which lasted all of 30 seconds before civil war resumed…), but it was a somewhat peripheral location Franciscans at Santa Croce and the Benedictins at the Badia. Thus Antoninus aspired to found a larger Dominican congregation, somewhere within the heart of the city. Even though monastic life is supposed to be cloistered and separate, a central location would bring prestige and influence. His attention focused on a small 12th century monastery in the north end of the city, built originally for Vallombrosan monks but occupied at the time by a small community of Benedictines, who were content to sell the property for the right price.

To muster the funds to buy the property and replace the cramped 12th century complex with a grand Renaissance one, Antoninus turned to his good friend Cosimo de Medici, who, in the first decades of the 1400s, was in the process of advancing from simply having a lot of money to controlling all of Florence with his money. Cosimo was very willing to spend on public works projects in general–both because it won the good will of the people and because he was worried about going to Hell for usury–and he was especially happy to spend on humanist and scholarly projects such as libraries, and setting up a community of scholar-monks to use said libraries. Antoninus extracted a lot of money from Cosimo over the years, not just for rebuilding and decorating San Marco, but for feeding and clothing the poor. Cosimo joked that it didn’t matter how much he gave, he could never close the books, he’d always be in God’s debt.

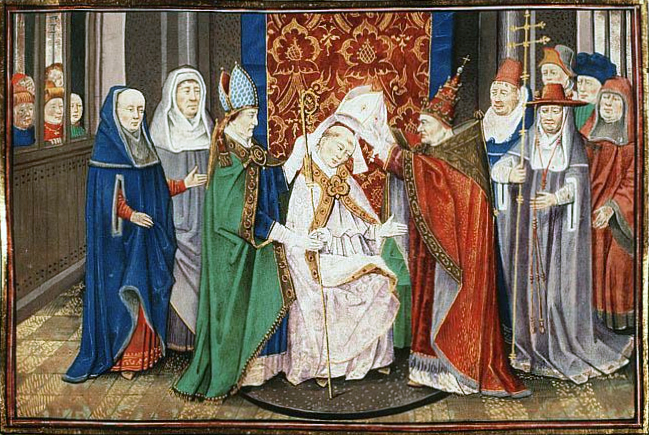

When Cosimo de’ Medici rebuilt the monastery for the Dominicans in 1433, Antoninus became the first prior of San Marco, and then became Archbishop of Florence in 1446. All archbishops of Florence in this period went through a mystical marriage with the Abbess of S. Pier Maggiore, which included a full wedding ceremony in the Duomo and spending a night in a special bed in the convent. Oddly enough, this incident, which is on record, does not appear in the great fresco cycle of Saint Antoninus’s life and miracles that decorates one of the courtyards in San Marco.

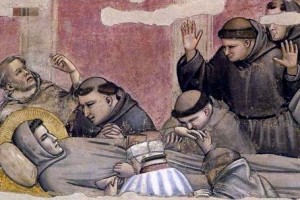

As well as feeding the poor, Antoninus went among them to give them last rites when they had the plague, which was a big deal. So many priests had refused to put their own lives at risk doing this in the Great Plague of 1348 that the pope at the time (Clement VI, one of the Avignon popes) granted an indulgence to everyone who died of it, meaning they’d go straight to heaven, which was probably the largest indulgence ever granted, as that plague killed a third of Europe.

While we tend to think of the Black Death sweeping through in 1348 and then leaving again, it was actually endemic in Europe until the 18th century, and fresh outbreaks were frequent in Italy throughout the Renaissance. There was a bad outbreak in Antoninus’s time, not as deadly since everyone alive in the 1420s was the child of somone who had resisted the 1348 outbreak so many had stronger immune systems (yay natural selection), but most people including priests still preferred not to have contact with the sufferers, so his ministration was exceptional.

Antoninus disapproved of gambling, cheating and usury. He didn’t have a dramatic life or dramatic miracles, but he was famous for living a simple and austere life even after he became famous and influential. He was also a great scholar and advocate of Church reform (which made his works popular during the Reformation and Counterreformation), not to mention incredibly popular with ordinary Florentines. As soon as Pope Leo X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de Medici i.e. Cosimo de Medici’s great grandson) was firmly seated on the Throne of St. Peter, he began the process of pushing for Antoninus’s canonization, but it was not completed until the (very brief) reign of Leo’s successor Adrian VI.

There’s an entire fresco-cycle running around the top of the first courtyard of San Marco devoted to Antoninus’s life of genuinely impressive public works and fairly unimpressive miracles. The most fun miracle is the time they had lost the key to a chest, and then he had a fish for dinner and the key miraculously turned up in the fish. He also performed some exciting exorcisms.

There’s an entire fresco-cycle running around the top of the first courtyard of San Marco devoted to Antoninus’s life of genuinely impressive public works and fairly unimpressive miracles. The most fun miracle is the time they had lost the key to a chest, and then he had a fish for dinner and the key miraculously turned up in the fish. He also performed some exciting exorcisms.

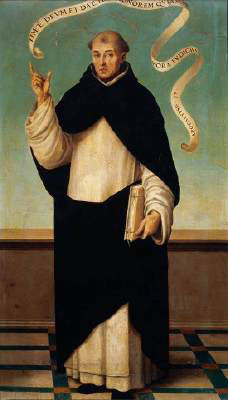

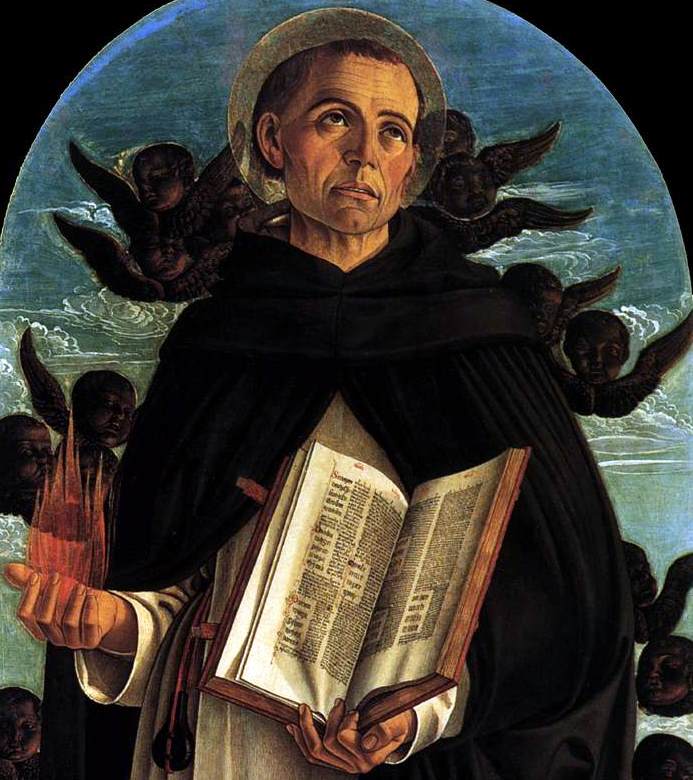

You very seldom see Saint Antoninus represented outside Florence — or even very far from San Marco, so he is usually recognizable by context. Are you in Florence, or looking at Florentine art? If so, that Dominican with a bishop’s white T-shaped sash is pretty certainly Antoninus. In general he is differentiated from other major Dominican saints by the white sash.

St. Vincent Ferrer

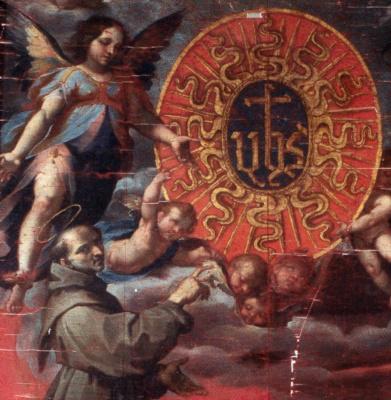

- Common attributes: Dominican robes, flame.

- Occasional attributes: Book, wings or winged cherubs, trumpet.

- Patron saint of: plumbers, construction workers

- Patron of places: Vannes (in Brittany), Valencia somewhat

- Feast days: April 5

- Most often depicted: With other Dominicans

- Relics: Vannes Cathedral

St Vincent Ferrer (1350-1419) was born in Valencia in Spain. He became a Dominican very young, and spent his life travelling around Europe preaching and converting Cathars and Jews. He was canonized by Pope Calixtus III (Alfons de Borja i.e. Rodrigo Borgia’s uncle), who himself came from Valencia — yes another hometown canonization.

Vincent Ferrer was a contemporary of Catherine of Siena, and the two of them ended up on opposite sides of the Western Schism. For those who need a refresher, in 1305, after a big fight between Pope Boniface VIII and the King of France over who got to appoint French bishops, a rough and frightened papal conclave elected a French pope, Clement V, who stayed in Avignon, and for the next several popes the papacy remained in Avignon, under the control of France. This ended when Pope Gregory XI returned from Avignon to Rome in 1377 and then died in 1378, but upon his death Rome elected one new pope (Urban VI) and Avignon elected another (Clement VII), and when these died yet more rival popes were appointed, until the whole mess was finally solved by the Council of Constance in 1416 (a long time to wait to know who’s pope!) During the controversy, Vincent Ferrer was a strong and loyal supporter of the Avignon popes (note that Avignon is quite close to Valencia), while Catherine of Siena supported the Roman popes, and was sent to argue for them as Florence’s ambassador (unsuccessfully but her work probably helped set the stage for later embassies). Thus the fact that both Vincent and Catherine were eventually canonized shows how spread out and complex the Dominican order was, and how it was often part of many different Church movements at once, even contradictory ones: pro-Spanish/French v. pro-Italian, pro-scholarly v. pro-mystic, and of course how, later on, it could at the same time be a great promoter of intellectual study and innovation and also run the Inquisition.

Vincent Ferrer was a contemporary of Catherine of Siena, and the two of them ended up on opposite sides of the Western Schism. For those who need a refresher, in 1305, after a big fight between Pope Boniface VIII and the King of France over who got to appoint French bishops, a rough and frightened papal conclave elected a French pope, Clement V, who stayed in Avignon, and for the next several popes the papacy remained in Avignon, under the control of France. This ended when Pope Gregory XI returned from Avignon to Rome in 1377 and then died in 1378, but upon his death Rome elected one new pope (Urban VI) and Avignon elected another (Clement VII), and when these died yet more rival popes were appointed, until the whole mess was finally solved by the Council of Constance in 1416 (a long time to wait to know who’s pope!) During the controversy, Vincent Ferrer was a strong and loyal supporter of the Avignon popes (note that Avignon is quite close to Valencia), while Catherine of Siena supported the Roman popes, and was sent to argue for them as Florence’s ambassador (unsuccessfully but her work probably helped set the stage for later embassies). Thus the fact that both Vincent and Catherine were eventually canonized shows how spread out and complex the Dominican order was, and how it was often part of many different Church movements at once, even contradictory ones: pro-Spanish/French v. pro-Italian, pro-scholarly v. pro-mystic, and of course how, later on, it could at the same time be a great promoter of intellectual study and innovation and also run the Inquisition.

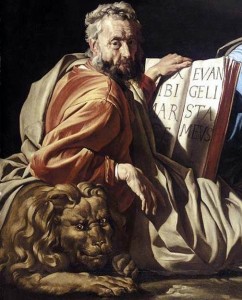

In art, at least outside Valencia and Vannes, Vinecnt Ferrer is generally just an extra Dominican. His most common attribute is a tongue of flame, either on his head or in his hand, though Antony of Padua sometimes has the same, as do apostles and evangelists, so make sure to look for the penguin robes before reaching for Vincent Ferrer as an identification. If Dominic and Thomas Aquinas and Peter Martyr are accounted for and there’s an extra one, even without attributes, it usually turns out to be Vinecnt Ferrer. So if you’re looking at a painting and there’s another male penguin monk who doesn’t he have a lily and a star, isn’t chubby, doesn’t have the ability to interpret Aristotle blazing from his chest like the son, and doesn’t he have a knife in his head or gore dripping down his shoulders, then he’s probably Vincent Ferrer. There’s a slight possibility he may be St Raymond of Penafort or St Hyacinth of Poland, higher if the picture is from Spain or Poland. Albertus Magnus is another possibility, but he is depicted rarely enough that he generally seems to get labelled.

In art, at least outside Valencia and Vannes, Vinecnt Ferrer is generally just an extra Dominican. His most common attribute is a tongue of flame, either on his head or in his hand, though Antony of Padua sometimes has the same, as do apostles and evangelists, so make sure to look for the penguin robes before reaching for Vincent Ferrer as an identification. If Dominic and Thomas Aquinas and Peter Martyr are accounted for and there’s an extra one, even without attributes, it usually turns out to be Vinecnt Ferrer. So if you’re looking at a painting and there’s another male penguin monk who doesn’t he have a lily and a star, isn’t chubby, doesn’t have the ability to interpret Aristotle blazing from his chest like the son, and doesn’t he have a knife in his head or gore dripping down his shoulders, then he’s probably Vincent Ferrer. There’s a slight possibility he may be St Raymond of Penafort or St Hyacinth of Poland, higher if the picture is from Spain or Poland. Albertus Magnus is another possibility, but he is depicted rarely enough that he generally seems to get labelled.

Spot the Saint Mini-Quiz

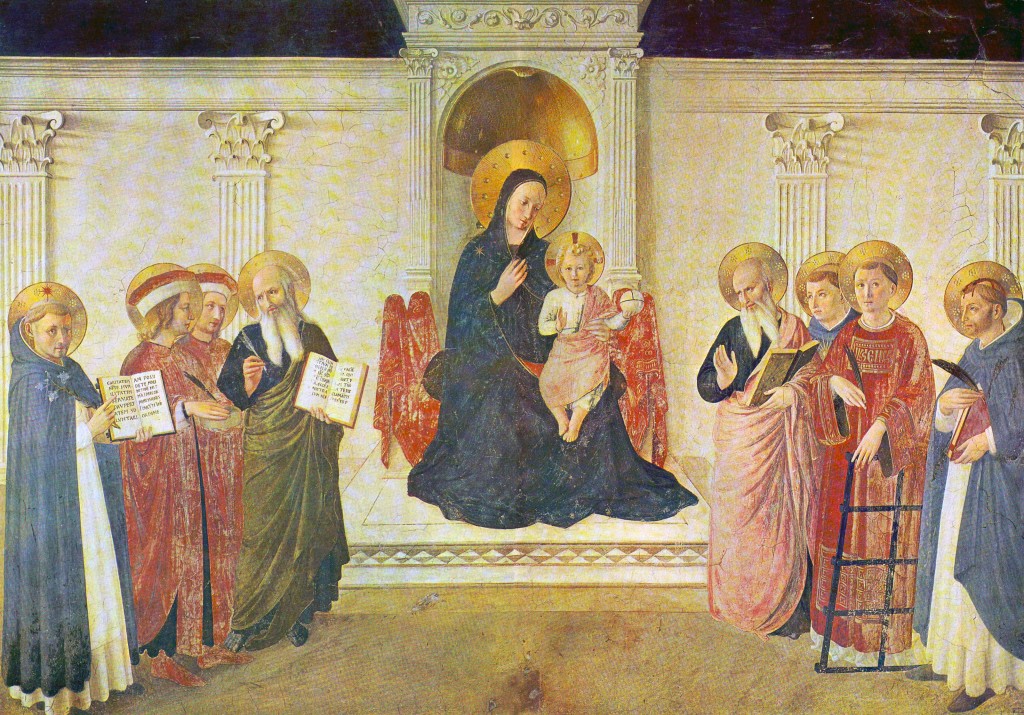

And now, for the first time in a long time, your spot-the-saint review quiz. If you review earlier Spot the Saint posts, you should be able to identify all these figures except the man all the way on the right, with a harp and a crown (though those of you with biblical knowledge can hopefully recognize him. Hint: he’s not a saint):

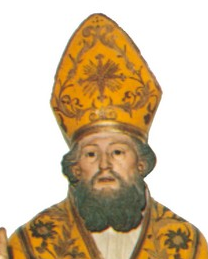

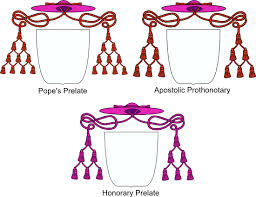

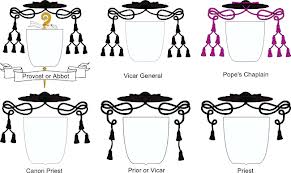

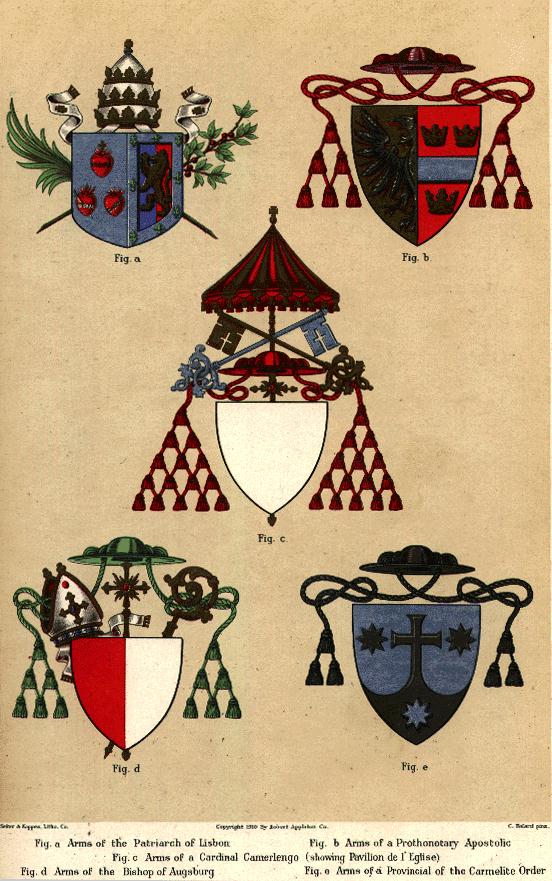

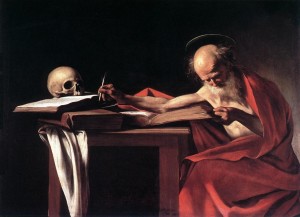

anyone who wants to become a Spot the Saint expert needs to get good at differentiating between different categories of hats. Some are easy to confuse with each other, but the critical basics are these:

anyone who wants to become a Spot the Saint expert needs to get good at differentiating between different categories of hats. Some are easy to confuse with each other, but the critical basics are these:

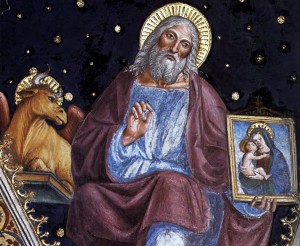

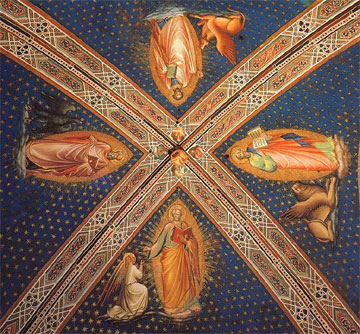

The Four Doctors of the Church

The Four Doctors of the Church

How can we be expected to tell them apart if they have no identifying attributes? Often the original context of the painting would make it clear, since it would be commissioned by or for devotees of a particular bishop saint, or in a city where a specific one was most popular. But since pieces are so often in museums now, sometimes all one can do is guess. Nicholas was one of the most popular bishop saints, along with Augustine and, in Florence, Zenobius, so in general Nicholas is a safe guess. When in doubt, the artist sometimes provides separate scenes as hints. Sometimes these are painted on separate panels below or above the main painting, showing a recognizable scene from the saint’s life. With bishop saints, sometimes scenes from their lives are embroidered on their robes, though this can be deceptive, since I’ve seen Saint Augustine with scenes from the life of Saint Stephen on his robe.

How can we be expected to tell them apart if they have no identifying attributes? Often the original context of the painting would make it clear, since it would be commissioned by or for devotees of a particular bishop saint, or in a city where a specific one was most popular. But since pieces are so often in museums now, sometimes all one can do is guess. Nicholas was one of the most popular bishop saints, along with Augustine and, in Florence, Zenobius, so in general Nicholas is a safe guess. When in doubt, the artist sometimes provides separate scenes as hints. Sometimes these are painted on separate panels below or above the main painting, showing a recognizable scene from the saint’s life. With bishop saints, sometimes scenes from their lives are embroidered on their robes, though this can be deceptive, since I’ve seen Saint Augustine with scenes from the life of Saint Stephen on his robe.