Cellini’s Perseus & the Violence of Renaissance Art

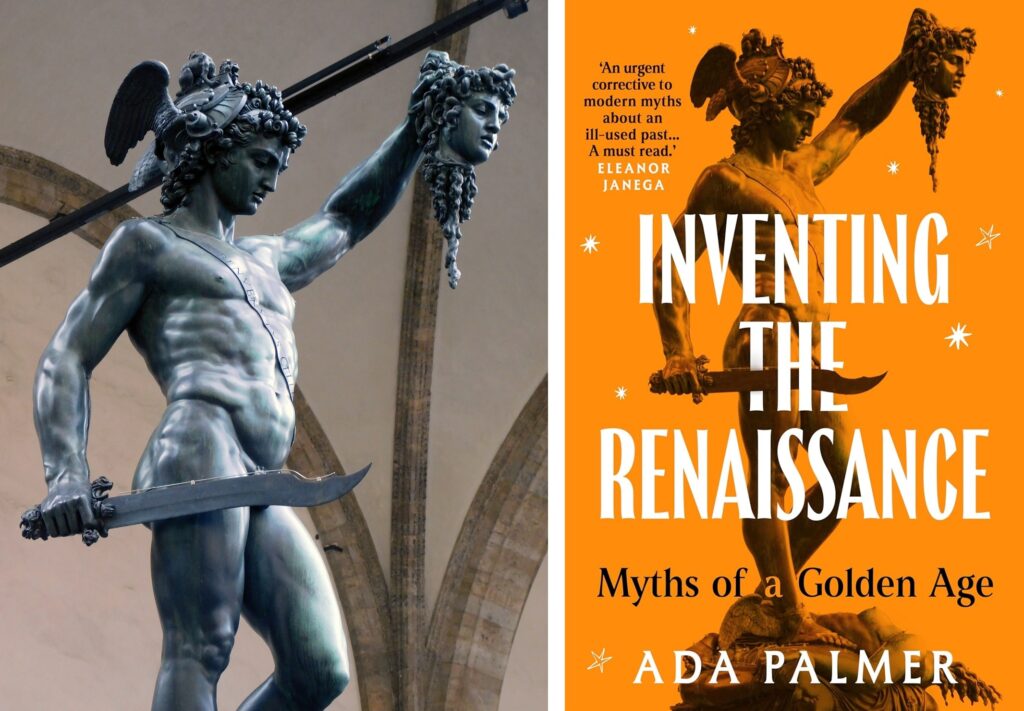

Inventing the Renaissance comes out in one month in the UK (2 months USA), so I’m going to try to post daily this month on social media to share cool pictures and stories of things related to the book. I thought I would also gather them here, posting them sometimes as individual posts, sometimes gathering a few together when they’re shorter. So to start here are some notes on Benvenuto Cellini’s stunning Perseus, my pick for a cover illustration (thank you, editors!)

For me, this statue personifies the Renaissance because, by standing opposite Michelangelo’s David by the Palazzo Vecchio, it’s part of a suite of famous statues every one of which commemorates some big & often violent tumult. When we meet famous Renaissance art we often hear about the artist but not the context. The severed head is there for a reason!

Cellini lived in the rocky decades when (after the death of the famous Lorenzo de Medici) the Medici family had been kicked out and strove to return and seize control of the city by force. Duke Cosimo I took over in the 1530s, and commissioned the Perseus in the 1540s right after a bloody revolt.

Perseus’s face deliberately resembled the then-teenaged duke, and Florence had long displayed corpses of traitors that square, often hung from battlements, sometimes as heads on pikes. When the statue was unveiled Medusa’s head in the duke’s hand represented very real & recent rebel heads!

To increase the gore factor, the statue is positioned at the edge of a roof, so when it rains Perseus remains dry, but water drips down the gore streaming from her head, from the sword point, and from her severed neck!

To hammer the message home, a relief at the bottom shows Perseus rescuing Andromeda (a personified Florence). In the top right corner a cavalry battle (which does not appear in the Perseus story!) shows the defeat of the rebels, as Perseus “rescues” Florence from the “dragon” of republican rule.

In the base, Jupiter, Perseus’s father, threatens to strike anyone who harms his son, a warning of reprisals from Cosimo’s allies, especially the Emperor whose Landsknecht knights Cosimo quartered under the very roof where the statue stood! Giving it its current name “Loggia dei Lanzi.”

When we celebrate Renaissance art w/o acknowledging the terror & violence that shaped it, we repeat the myth of a bad “Dark Ages” & Renaissance “golden age” a very potent piece of propaganda, which is what Inventing the Renaissance is about, and it has plenty more Cellini anecdotes, he was a wild man who lived a wild life, documented by his book which I will always call “The Implausibly Interesting Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini.”

I hope you’ll enjoy more tidbits like this in coming days!

One Response to “Cellini’s Perseus & the Violence of Renaissance Art”

-

[…] did fight the ducal takeover. Cellini’s Perseus statue, the topic of my first thread in this series, commemorated Duke Cosimo crushing of one violent uprising, & his desire to cast the severed […]