Censorship Project + A Brief History of Book Burning

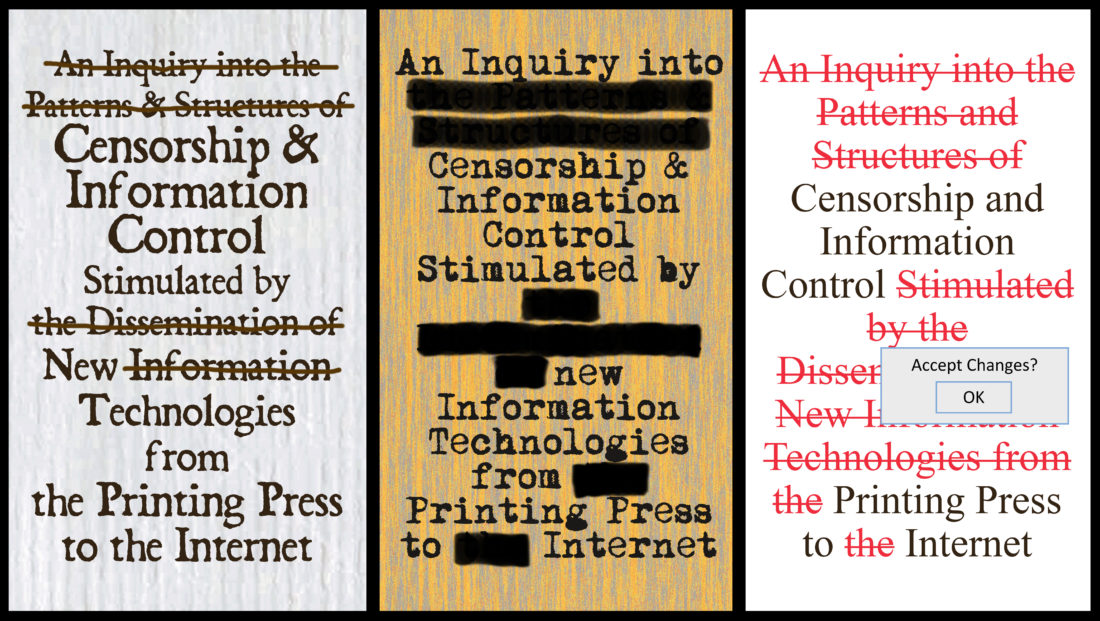

Today I’m delighted to announce my big new project, a collaboration with Cory Doctorow and Adrian Johns: Censorship and Information Control during Information Revolutions

You can learn about it from the project website, and support it on Kickstarter.

The idea: Revolutions in information technology always trigger innovations in censorship and information control, so we’re bringing together 25 experts on information revolutions past and present to create a filmed series of discussions (which we will post online for all to enjoy!) which we hope will help people understand the new forms of censorship and information control that are developing as a result of the digital revolution. And we’ve put together a museum exhibit on the history of censorship, a printed catalog with 200+ pages of full color images of banned and censored books, which you can get as a Kickstarter thank-you. More publications will follow.

For those who’ve wondered why there haven’t been many Ex Urbe posts recently, the work for this project has been a big part of it, though other real reasons include my chronic pain, and the tenure scramble (victory!), and racing to finish Terra Ignota book 4, and female faculty being put on way too many committees (12! seriously?!). But now that the preparatory work of the project is done, I should be able to share more here over the coming weeks and months.

The project was born out of Cory Doctorow and me sitting down at conventions from time to time and chatting about our work, and over and over something he was seeing current corporations or governments try out with digital regulation would be jarringly similar to something I saw guilds or city-states try during the print revolution. One big issue in both eras, for example, was/is the difference between systems that try to regulate content before it is released, i.e. requiring books to have licenses before they could be printed, or content to be vetted before it is published (think the Inquisition, the Comics Code Authority, or movie ratings in places like New Zealand where it’s illegal to screen unrated films), vs. systems that allow things to be released without oversight but create apparatus for policing/ removing/ prosecuting them after release if they’re found objectionable (like England in the 16th century, or online systems that have users flag content). Past information revolutions–from the printing press, to radio and talkies–give us test cases that show us what effects different policies had, so by looking, for example, at where the book trade fared better, Paris or Amsterdam, we can also look at what effects different regulations are likely to have on current information economies, and artistic output. We’ve got people who work on the Inquisition, digital music, the birth of copyright, ditto machines, Google, banned plays, burnings of Jewish books, comic book censorship, an amazing list!

There will more to share over the next months as the videos go online, but today I want to share one of the fun little pieces I wrote for exhibit on Book Burning. Writing for exhibits is always an extra challenge, since only so much can fit on a museum wall or item label, so, 2+ millenia of of book burning… can I do it justice in 550 words?

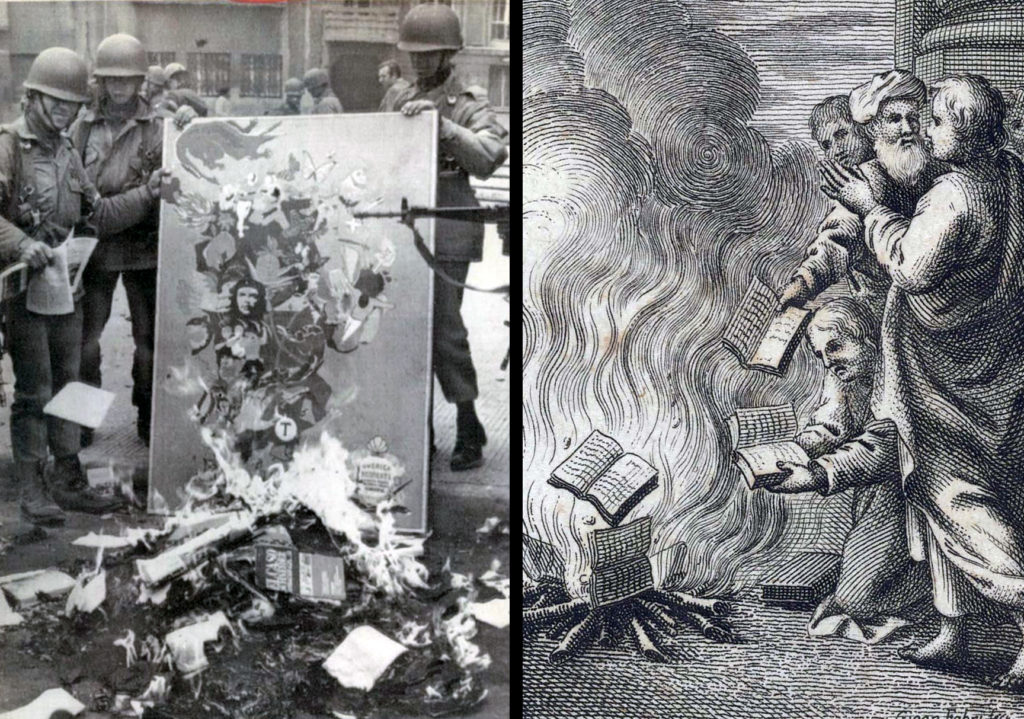

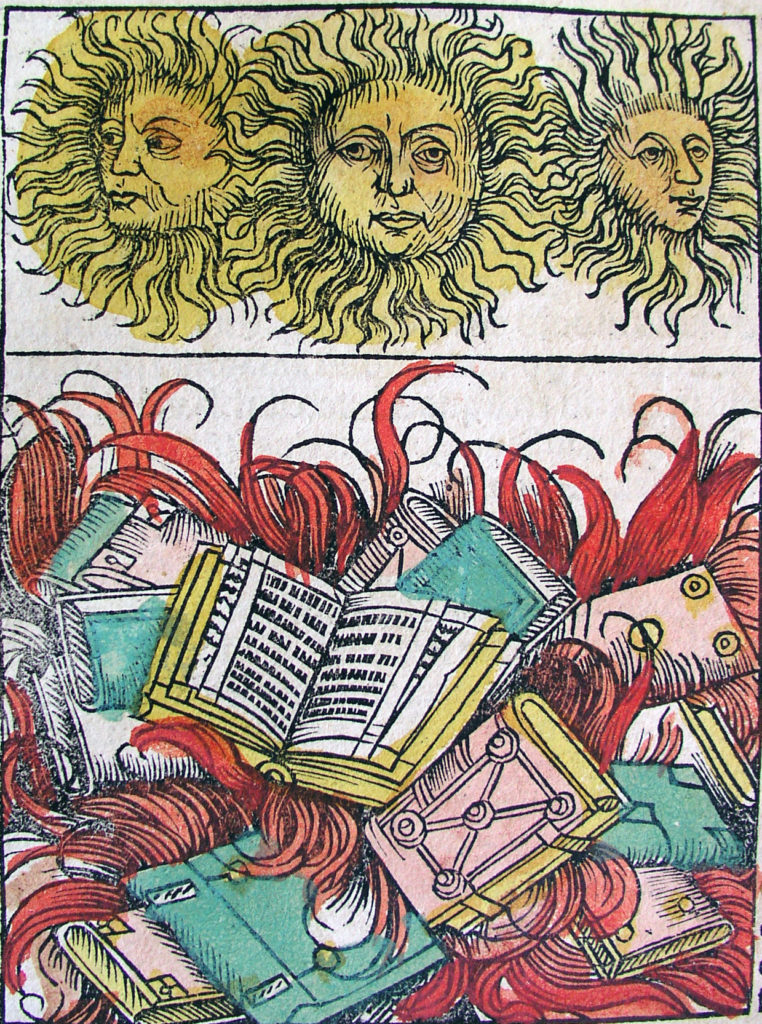

We can divide book burnings into three kinds: eradication burnings which seek to destroy a text, collection burnings which target a library or archive, and symbolic burnings which primarily aim to send a message.

The earliest known book burnings are one mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Jeremiah 36), then the burning of Confucian works (and execution of Confucian scholars) in Qin Dynasty China, 213-210 BC. Christian book burning began after the Council of Nicaea, when Emperor Constantine ordered the burning of works of Arian (non-Trinitarian) Christianity. In the manuscript era eradication burnings could destroy all copies of a text—as in 1073 when Pope Gregory VII ordered the burning of Sappho—but after 1450 the movable type printing press made eradication burnings of published material effectively impossible unless one seized the whole print run before copies were dispersed. This was difficult for even the Inquisition, but it still practiced frequent symbolic book burning, especially in the Enlightenment, when a condemnation from Rome required Paris to publicly burn one or a few copies of a book, while all knew many more remained. When the beloved Encyclopédie was condemned, the French authorities tasked to burn it burned Jansenist theological writings in its place, a symbolic act two steps removed from harming the original.

Since print’s advent eradication burnings have diminished, though collection burnings continue, often targeting communities such as Protestant or Jewish communities, language groups such as indigenous texts in Portuguese-held Goa (India), universities whose organized collections are unique even if individual items are not, or state or institutional archives which contain unique content even in an age of print. Regime changes and political unrest have long been triggers for archive burnings, such as the burning of the National Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2014. Some book burnings result from smaller scale conflicts, as in 1852 when Armand Dufau, in charge of the school for the blind in Paris, ordered the burning of all books in the newly-invented braille system, of which he disapproved. Nazi burnings of Jewish and “un-German” material employed eradication rhetoric but were mainly collection burnings, as when youth groups burned 25,000 books from university libraries in 1933, or symbolic burnings, performing destruction to spread fear among foes and excitement among supporters while many party members retained or sold valuable books stolen from Jewish collections rather than destroying them.

Today, archived documents and historic manuscript collections remain most vulnerable to eradication burning, such as those burned in Iraq’s national Library in 2003, in two libraries in Tumbuktu in 2013, and others recently burned by ISIS. Large-scale book burnings in America have included the activities of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (founded 1873) which boasted of burning 15 tons of books and nearly 4 million “lewd” pictures, burnings of comic books in 1948, and burning of communist material during the Second Red Scare of the 1950s. Since then, most book burnings in America have been small-scale symbolic burnings of works such as Harry Potter, books objected to in schools or college classrooms, or of Bibles or Qur’ans. In a rare 2010 case of an attempted eradication burning, the Pentagon bought and burned nearly the whole print run of Antony Shaffer’s Operation Dark Heart, which—authorities said—contained classified information.

Not bad for 550 words! If you enjoyed this there’s more to come, so please check out the project. And please consider supporting us on Kickstarter. Thank you!

10 Responses to “Censorship Project + A Brief History of Book Burning”

-

In a rare 2010 case of an attempted eradication burning, the Pentagon bought and burned nearly the whole print run of Antony Shaffer’s Operation Dark Heart, which—authorities said—contained classified information.

I’m so confused as to how that could be expected to work. Let’s suppose that they were successful in buying and burning the entire print run. That still means they’re still buying them. I’m just imagining it:

Shaffer: So…. you bought the entire first print run. In order to burn it.

Pentagon: We sure did.

Shaffer: Sweet! Looks like the second print run is basically guaranteed to sell out just as fast, then! Who knows how far this could go with your help? A third print run? A fourth? A fifth?And then of course later he can just go put it up for free on the internet anyway.

(Also, congratulations on tenure!)

-

From the Amazon page for the book:

“On Friday, August 13, 2010, just as St. Martin’s Press was readying its initial shipment of this book, the Department of Defense contacted us to express its concern that our publication of Operation Dark Heart could cause damage to U.S. national security. After consulting with our author, we agreed to incorporate some of the government’s changes into a revised edition of his book while redacting other text he was told was classified. The newly revised book keeps our national interests secure, but this highly qualified warrior’s story is still intact. Shaffer’s assessment of successes and failures in Afghanistan remains dramatic, shocking, and crucial reading for anyone concerned about the outcome of the war.”

So the answer is “combine buying almost the entire print run with “persuading” the author and publisher to have later editions be redacted versions.

-

Also, yay, tenure!

-

-

[…] a very timely recent post (it went up while I was working on this essay!), author Ada Palmer points out there’s also a […]

-

Congratulations on tenure! I hope your pain is easing, and look forward to future updates.

-

[…] Censorship Project + A Brief History of Book Burning […]

-

There’s an earlier Christian book burning in the Book of Acts, in which new converts burn magic books.

-

Do you have the citation? I’d love to add it.

-

-

The relationship between fiction and history occurs many times in literature. In a historical fiction novel, the author uses real characters that the reader knows along with invented or “fictional” characters. At the same time, the resource of using historical characters in fiction, what is achieved is to eliminate the barrier or border between fiction and reality and bring both worlds together, getting a story that is neither true nor false, a path between pure fiction and history….