History’s Largest & Most Famous Disability Access Ramp

Time for the largest, most famous disability access ramp in the world, paired with a twist about how our feelings about a piece of history can reverse completely based, not just on the historian’s point of view, but what questions we start with.

Time for the largest, most famous disability access ramp in the world, paired with a twist about how our feelings about a piece of history can reverse completely based, not just on the historian’s point of view, but what questions we start with.

(Part of my series of posts counting down to the release of Inventing the Renaissance)

Florence’s Medici had a family curse: an agonizing hereditary medical condition causing torturous joint pain and severe mobility restrictions, so it was agony to stand, walk, or even hold a pen. Yes, Renaissance Florence, cradle of the Renaissance, was run by disabled people from a sickbed. The famous Cosimo had to have servants carry him through his own home, and used to shout every time they neared doorway. When asked, “Why do you shout before we go through a doorway?” He answered “Because if I shout after you slam my head into the stone lintel it doesn’t help.”

We have a visitor’s account of visiting Palazzo Medici in the days of Cosimo the elder (1440s) and meeting Cosimo and both his sons lying side-by-side three in a bed in pain “each as cranky as the last” using their sickroom as their office as they directed staff in running the republic. Most texts call the Medici condition “gout” a word with the stigma of being the “rich man’s disease” caused by gluttony—a reputation less borne out by modern science. Diet does affect it, mostly alcohol which *everyone drank all the time* and avoiding seafood and organ meat. It isn’t caused by overeating etc. Now, gout in the modern sense is an agonizing joint pain condition caused by buildup of uric acid in the joints, but when a period source says “gout” they could mean any condition that cause swelling, inflammation, and/or pain, from basic arthritis through coeliac to rarer things.

I talked in my earlier thread [add link here] about Clarice Orsini’s EXTREMELY ILLEGAL hat about how important it was for Medici men like her husband Lorenzo to perform humility. Florence had killed/expelled its nobles, it was a merchant republic and demanded merchant dress & merchant comportment. One had to be seen in the city always walking (riding or being carried was too princely), greeting peers in the street, bowing to each other—are you wincing by now? Imagining walking those stone cobbles while every joint in your body feels like it’s on fire? And going up tall stone staircases?

Add the fact that Europe’s normal diplomatic class at the time were all nobles, so every envoy from anywhere is at least the son of a baron and must be greeted with obsequious bowing and scraping, and walking along beside his horse leading it to where he’ll be staying, as an act of symbolic servant-like humility. Ow.

Mature Medici—Cosimo, Piero, Lorenzo, Lorenzo’s mom Lucrezia Tornabuoni had it to—all had to save their endurance for *performing fitness* in the streets, being seen walking to or from the cathedral or church or the Palazzo Vecchio where wary eyes judged them, collapsing back into their beds and servants’ arms (period wheelchairs) the instant the door closed. It was carefully stage-managed agony, and accounts from visitors describe Lorenzo walking alongside their horses, joining dances and parades—performance of fitness necessary to hide his increasing weakness.

Lorenzo’s pain was likely worst, since bone examination suggests that, on top of the family condition, he also had acromegaly, the growth hormone overproduction that makes your bones keep growing & swelling at the joints. 2x debilitating arthritis!

And if you remember my post about the very, very tall towers of the Renaissance, imagine with me the agony of answering the summons to visit the Priori (ruling council). A great honor! But a good floor higher than the tower I lived in that was up 111 steps!

A photograph of Florence’s beautiful Palazzo Vecchio. An arrow points out where the room to meet with the priori was located, on an upper floor above the skyline of the rest of the city, meaning a floor above being up 111 steps!

You couldn’t be carried (Princely! Ambitious!) you had to go on foot. Once Lorenzo’s father Piero on a really, really bad pain day when summoned asked if, for once, the priors could visit him. There were riots, and an assassination attempt. How dare he *summon* the senators like a duke his servants! Books where the Medici are the bad guys (tyrants who corrupted the republic!) will make this incident proof of Piero’s haughty decadence. But I know can’t do those stairs on a pain day, and we could equally call it a disability accommodation. He’s still called “Piero the Gouty” to this day.

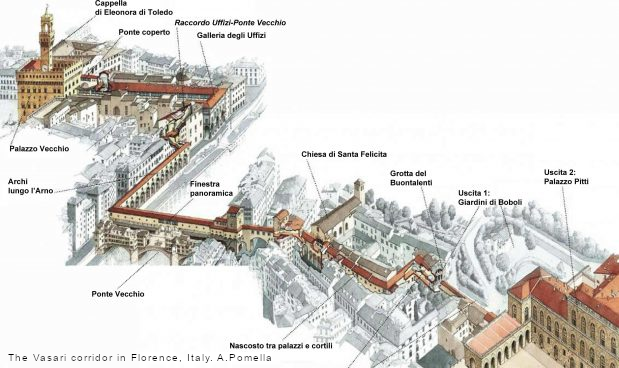

Speaking of disability accommodations, eventually the Medici built a ramp. This ramp. It connects from the floor where the priori were, passes through the bureaucratic offices and all-important guild HQs, sloping at an easy grade down to the living-quarters level of the family palace.

The long interior descends at a gentle grade with minimal turns and staircases, mostly stair that a horse can climb—horse ramps and riding horses or donkeys *indoors* at a walk was another proto-wheelchair disability tool, one architecture had to plan for with things like horse stairs.

This is why the Vatican has so many weirdly shallow staircases—popes are old so the Vatican was a palace expecting to always host a disabled monarch, so it’s full of built-in accommodations, the most complex and fascinating accessible architecture case study in the world.

And it’s not chance that it was the first Medici pope, Lorenzo’s son Leo X, who finally installed a donkey-powered elevator in the papal fortress Castel Sant’Angelo. Leo was elected young, still fairly fit, but had memories of his parents’ condition getting worse, and knew his would.

So, Lorenzo’s descendants finally built Earth’s largest, most famous disability access ramp. It’s name is the Vasari Corridor, the elevated walkway I discussed last week as conquering Duke Cosimo I’s project of architectural domination, the tyrant’s assassin-proof walkway piercing the city’s heart. Diversity celebration or tyrant’s monument? It’s the same piece of architecture but feels completely different depending on what question we ask about it: Why was it built? For power? For chronic pain? Yes. Both.

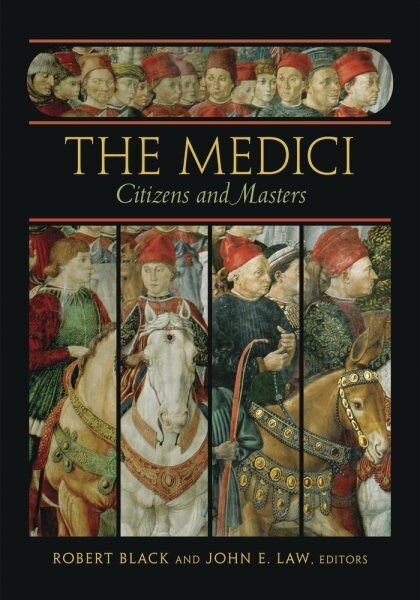

Years ago I attended a conference on “The Medici: Citizens or Tyrants?” Dozens of scholars presented evidence for the family’s sincere, humble service to the republic, or for their princely power-hungry cunning. ALL the presentations had GREAT evidence, and, in the end, they came out exactly fifty-fifty: half showing evidence for humble servants of the state, half scheming tyrants. You can read the papers in this incredible book. We always worry about bias in history, but one part of bias is: What question were you asking in the first place?

Was Piero the Gouty demanding the obsequious submission of the priori (like summoning the Senate to the White House) or a disability accommodation just this once? Both, is the answer, but the same questions won’t get to both, it takes different historians asking different questions then comparing.

“Inventing the Renaissance” is a history of histories of this supposed golden age, and much of the process of making history lies in adding new questions to the braid as historians ask new and more diverse questions with each generation.

4 Responses to “History’s Largest & Most Famous Disability Access Ramp”

-

I have zero ambition to power or prestige so it’s amazing to me that having such qualities could instill such intractable determination that those guys could do their work (and social obligations) in spite of their suffering. I get a headache and have to lie down. I can’t conceive of it. If nothing else, they had guts!

-

Fascinating, both about Florence and historical mobility disability!

Never mind the animal mobility aids – donkeys and such – is there any record of proto-(real)wheelchairs in Renaissance Italy? Seems like a ‘natural’ for Leonardo.

-

It’s interesting that when dealing with noble diplomats, they’d perform displays of servitude, because it (and various other things you describe) seem to accept the legitimacy of the idea of nobility — they’re not saying “the idea makes no sense”, they’re just saying “we don’t have any here”. If people think the idea is nonsense you don’t have to fear looking like one!

-

Actually wait that’s not true… you definitely would still worry about that, if you’re doing things that are distinctly noble and others aren’t. But: 1. you would presumably open these things up to other non-nobles so that you wouldn’t be alone and doing it, so it would no longer be so distinctive, and 2. you definitely wouldn’t make a show of deference to nobles!

-