Why I Teach Machiavelli Through His Letters

Hello! It’s been a while since I posted since, as usual, many projects press, so it’s rare for me to have the time to write the kinds of polished essays I like sharing here. But I’ve been hoping to share more things, since a lot of the history work I’ve been doing lately has helped me with reflecting on current events, and I want to share that faster than the slow grind of book-length work and academic journals will allow. So I’m going to start posting a few things here that are a little rougher. I hope to still post formal essays a few times a year as before, but I’m going to start also sharing things like transcripts of lectures or talks I’ve given, excerpts from my teaching notes, or assemblages from Twitter threads which took meatier turns. I hope you’ll enjoy them, but I’ll also try to always make clear what kind of content each post is, so you know which are the polished essays you’re used to.

I’m also launching a Patreon, so if you’ve enjoyed my posts, books, music etc. please consider supporting me.

I’ve felt torn about Patreon for a long time since, unlike so many wonderful scholars and authors I know, I have a steady living wage from my university and don’t struggle to get by. But, as my Patreon page explains, what I don’t have enough of is the means to hire help. As someone trying to create a lot (and as a chronic pain sufferer who often has fewer than 7 days in my week) it makes an enormous difference to how much I can do if I can pay for help: pay a music editing service to turn polish vocal tracks into completed albums without spending hours on it myself, to pay my part-time assistant Denise who helps with my calendar and paperwork and fire-hose of email which so easily eat up whole days, to hire a sound editor to finally make it possible to launch a podcast with my good friend Jo Walton talking about books, and craft of writing, and history, and science, and Florence, and gelato, and interviewing awesome friends. Even the little post below was made possible by having help, and wouldn’t exist otherwise. And supporters will get updates on what I’ve been up to, and early access to blog posts and podcast episodes, and snippets of outtakes and works in progress. So if you’d like to help me hire the help I need to turn more ideas into reality, and to have more time to write, please have a look at the Patreon page for details, and thank you very much!

Meanwhile…

Why I Teach Machiavelli Through His Letters

(excerpt from a lecture transcript, so this is how I explain this to students too)

Teaching Machiavelli through his letters is a separate thing from being an historian accessing Machiavelli through his letters. One of the reasons that I love teaching Machiavelli through his letters is that you get a very different view of the person from letters. You get unimportant details. You get the things that the person cared about that week, as opposed to the things that the person wanted to be discussed by many people in the context of that person’s name for a long time. You do get the serious political thought, but you get it mixed with “Where is my salary?” “Hello my friend,” “Here’s the party I was at,” “I have a cold,” all of these very human elements that don’t come to us when we just read a thesis.

Teaching Machiavelli through his letters is a separate thing from being an historian accessing Machiavelli through his letters. One of the reasons that I love teaching Machiavelli through his letters is that you get a very different view of the person from letters. You get unimportant details. You get the things that the person cared about that week, as opposed to the things that the person wanted to be discussed by many people in the context of that person’s name for a long time. You do get the serious political thought, but you get it mixed with “Where is my salary?” “Hello my friend,” “Here’s the party I was at,” “I have a cold,” all of these very human elements that don’t come to us when we just read a thesis.

Thanks to interdisciplinarity, both at University of Chicago and elsewhere, I move from department to department a lot–I spend some of my time with historians, and some with classicists, political science people, Italian literature or English literature people, and with philosophy people. Each of these disciplines has a different way of approaching text, but many of them approach the text perhaps not with the formal philosophical attitude of “death of the author, we care only about the text,” but all the same with the effective attitude of “we try to learn about this author only through the text,” and only through the formal polished text, the treatise.

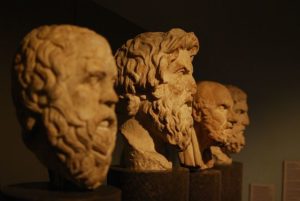

When I’m trying to unpack not only Machiavelli but history in general to my students, it’s very easy for the history to seem like a sequence of marble busts on pedestals who handed us great books. It’s much harder to get at the fact that those people are also people who are like us: people who messed up, people who ran out of money, people who had anxieties, people who failed in things that they undertook. People who had friends, people who were nervous without their friends, and lonely. And that isn’t a version of history that we get shown very often. We get shown heroes, we get shown villains, and we get shown geniuses, as if there isn’t a person present as well. Machiavelli is a very valuable example, because we have such a great corpus of letters, but he’s also such a name. If you want to make a shortlist of people who are a marble bust on a pedestal in the way that they’re presented as we talk about the history of thought, Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Cicero, Machiavelli, are major major figures in that way. So the letters humanize them and make them real.

When I’m trying to unpack not only Machiavelli but history in general to my students, it’s very easy for the history to seem like a sequence of marble busts on pedestals who handed us great books. It’s much harder to get at the fact that those people are also people who are like us: people who messed up, people who ran out of money, people who had anxieties, people who failed in things that they undertook. People who had friends, people who were nervous without their friends, and lonely. And that isn’t a version of history that we get shown very often. We get shown heroes, we get shown villains, and we get shown geniuses, as if there isn’t a person present as well. Machiavelli is a very valuable example, because we have such a great corpus of letters, but he’s also such a name. If you want to make a shortlist of people who are a marble bust on a pedestal in the way that they’re presented as we talk about the history of thought, Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Cicero, Machiavelli, are major major figures in that way. So the letters humanize them and make them real.

I feel it’s important not to approach these works as if these people are somehow superhumanly excellent, as if these people are somehow perfect in what they undertake. I’ll often be at a conference where someone will talk about a passage in a work in isolation. I was recently at the Renaissance Society of America conference, and there was an interesting discussion of a passage in which Ficino had a really weird interpretation of this one passage of Lucretius. And there was a very nasty fight between two scholars over the interpretation, in which one of the scholars insisted he’s making this complicated subtle three-part reading of a thing that relates to another thing, diagram diagram diagram. The other person said “I think he translated the passage wrong. Because the passage was really hard. And his copy didn’t have a very clear script. And I think he didn’t read the sentence the way we read the sentence.” And the first person was adamant that it is inappropriate to question whether someone like Ficino might have had trouble reading a piece of Latin, that of course his Latin is immaculately better than our Latin. And his Latin was better than our Latin, because he spent more of his life doing it and I do believe he’s better than most classicists at this — but most classicists really struggle with that line. And when you read the commentaries on it there’s lots of ambiguity even now about what it means, and we have dictionaries, which he did not.

It was very interesting to me to see that battle between thinking of the figure as human, in which the question “Did he mess up?” is a valid question, as opposed to thinking of the person as someone who could never mess up. And a lot of the ways we approach historical figures, whether it’s Machiavelli, or Aristotle, or anyone, involve the idea that all of their works are fully intended, that they’re somehow in an a-temporal vacuum, that we should look at them all in sequence, that no one is ever going to change his mind about a thing unless the person themselves made changing their mind about a thing be a big deal. We create this idea of these geniuses where everything they wrote even from early on is exactly what they meant, which then all gets incorporated into material.

It was very interesting to me to see that battle between thinking of the figure as human, in which the question “Did he mess up?” is a valid question, as opposed to thinking of the person as someone who could never mess up. And a lot of the ways we approach historical figures, whether it’s Machiavelli, or Aristotle, or anyone, involve the idea that all of their works are fully intended, that they’re somehow in an a-temporal vacuum, that we should look at them all in sequence, that no one is ever going to change his mind about a thing unless the person themselves made changing their mind about a thing be a big deal. We create this idea of these geniuses where everything they wrote even from early on is exactly what they meant, which then all gets incorporated into material.

I want my students to come away from my courses not thinking about historical figures like that, but remembering that every historical figure had to pay for socks, or had to deal with laundry, or have a servant who dealt with laundry for them and then they had to deal with the servant. But they all had everyday practical existences, and they all mess up. Machiavelli’s letters give you access to somebody who feels like a real human being. Some of the things he’s doing are really weird. Some of the things he’s doing involve bizarre sexuality. Some of the things he’s doing involve uncomfortable politics. Some of the things he’s doing involve very astute politics. Some of them involve very terrifying moments like his wife saying: “I’m so glad you’re alive, we heard that Cesare Borgia massacred all of his people, I’m so glad you’re alive!” And others are very much “We’re trying to get my brother a job and no one will give him a job because it was corruptly given to the other person and we have to figure out how to get my brother a job,” which is not the sort of thing we imagine such people giving their hours to.

When you read Michelangelo’s autobiography there’s an interesting point in it where he stops talking about art for a while and starts talking about the lawsuit that went on between him and people associated with Giuliano della Rovere because he was contracted to build Giuliano della Rovere’s tomb, but then for a variety of complicated reasons the tomb did not materialise as it was supposed to have, largely because the plan for the tomb was the most insane ridiculous over-the-top impossible tomb that you could ever possibly conceive of. That was obviously never going to happen. But also there were lots of fights between him and della Rovere over who had to pay for the marble and whether the marble was delivered and he said the marble was delivered and Della Rovere said the marble wasn’t delivered and there was a crack in it… and all these lawsuits went back and forth, and also Guiliano della Rovere was starting a giant war and invading Ferrara. At one point Michelangelo ran away from Rome saying “I’m not going to work on this stupid tomb any more” and went to Florence, and then Giuliano della Rovere moved an army over to besiege Florence and started threatening them “Florence! I will besiege you and burn you down unless you give me back Michelangelo!” We have these great documents where Michelangelo is begging Signoria “Please don’t make me go back to Della Rovere! I hate him and he just torments me. I’ll build you really good defensive walls! Look at my engineering ideas for how to improve the walls!” and they had to say “No, I’m sorry Michelangelo, we’re not going to war with the Battle Pope just for you, go back to Rome, build the stupid thing.” And he did go back to Rome, and then Della Rovere made him paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling knowing Michelangelo hated painting, basically as punishment for trying to run away. I’m not exaggerating. And that’s why there are lots of angry figures in the Sistine Chapel ceiling. But the wonderful horrible flirtatious strange antagonism between Michelangelo and Giuliano della Rovere is magnificent.

And in his autobiography he’s talking about this lawsuit that arose because of the della Rovere tomb project, in great detail, and then there’s a line that says Michelangelo realized that, while dealing with a bunch of lawsuits and Pope Adrian and such, he’d been so stressed he hadn’t picked up a chisel in four years. Because he spent the entire time just dealing with the lawsuit. (Anyone feeling guilty about being overwhelmed by stress this year, you’re not alone!) And we have four years worth of lost Michelangelo production, because he didn’t do any art that entire time, because he was just dealing with a stupid lawsuit. And that’s not the sort of thing that fits into our usual way of thinking about these great historical figures. We imagine Michelangelo in his studio with a chisel. We do not imagine him in a room with a bunch of lawyers being curmudgeonly and bickering and trapped in contract hell.

Those sorts of things are important, I think, to reintroduce into the way we imagine historical figures. That they have an everyday mundanity that we imagine that they don’t. And I think that’s a big part of why when we compare ourselves to them we feel as if we can’t live up to that greatness. Because we tell edited versions of the lives of great men and great women, in which we edit out the things that feel like us. So of course we feel as if our everyday lives full of mundanity can’t rise to those levels, because we’re not comparing ourselves to the real people, we’re comparing ourselves to the edited version in which we take out the mundanity! So Machiavelli’s letters give us that. And they give us a person with problems, and a person with mistakes, and a person with a sense of humor, and a person with sexuality, all of these elements we erase from our marble busts on pedestals. And so that’s a big part of why I use the letters while teaching, and when my students read them I want them to put together “Here is a real person who is like us,” as well as “Here is the everyday on the ground experience of what it’s like to live in this crisis.”

We need that, when we live in a real crisis ourselves, and it makes us feel so often like we’re powerless and weak compared to these impressive people in the past–but they felt that way too.

11 Responses to “Why I Teach Machiavelli Through His Letters”

-

Michelangelo wrote a wonderful poem about painting the Sistine Chapel.

A translation by Gail Mazur here:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57328/michaelangelo-to-giovanni-da-pistoia-when-the-author-was-painting-the-vault-of-the-sistine-chapelAnd a rhymed translation (behind a paywall) by Joel Agee here: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2014/06/19/giovanni-da-pistoia/

“Not to be trusted, though,

are the strange thoughts that through my mind now run,

for who can shoot straight through a crooked gun?

My painting’s dead. I’m done.

Giovanni, friend, remove my honor’s taint,

I’m not in a good place, I cannot paint. “ -

Hey, I’m a fan already! Please excuse my ignorance, but what does “S.P.Q.F” mean?

-

Derived from Senātus Populusque Rōmānus (SPQR) – Senate and People or Rome, aka the Roman Republic, SPQF is an imagined state of the same thing, but for 15-16th century Florence. Dr. Palmer often uses that as shorthand for Florence (and Italy) as Machiavelli and other thinkers of the Renaissance wanted them to be. As opposed to the chaotic mess they actually were.

-

-

Where might one find a nice list of his letters? Thanks for the thoughtful post!

-

You can read all the letters in this great translated collection: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/books/1101388040;jsessionid=7960F174AB9C87A147FE3345980C6CD4.prodny_store01-atgap08

-

-

SPQR is the old Roman slogan that means “Senatus Populus-que Romanus” i.e. “The Senate and the People of Rome” so SPQF is the Florentine version – many towns in Italy when they were independent citystates made their own variants, SPQB for Bergamo and so on.

-

It reminds me of Mary Beard’s story about Fergus Millar visiting her class. Students were ready to debate or dig into The Emperor in the Roman World. “They were sharpening their daggers, but turned out to be completely surprised by what they heard. He talked about trying to get his ideas together while pushing his kids in a buggy around the park (what? A senior male academic with a buggy?) and he explained that the introduction is often the bit you write last, in a hurry, and maybe you don’t always put what you want to say as well as you might (what? A senior male academic suggesting that he might not have been 100% correct?).”

https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/remembering-fergus-millar-disagree/

-

Thank you! I had a feeling it had to do with SPQR but my academic mind wanted it in written. I’m really enjoying the SPQF series. You make me wish I had majored in history!

-

[…] I Teach Machiavelli Through His Letters […]

-

[…] For example, Michelangelo, who lost four years of work to a lawsuit: […]

-

[…] work, who points out history is full of people who have had to put their work on hold for one reason or […]