Machiavelli I – S.P.Q.F. (Begins Machiavelli Series)

My year in Florence has flown by, leaving me to face up to a life without battlements and medieval towers, without Botticelli and Verrocchio, without church bells to inform me when it’s noon, or 7 am, or 6 am, or 6:12 am (why?), without squash blossoms as a pizza topping, without good gelato within easy reach, and without looking out my window and realizing that the humungous dome of the cathedral is still shockingly humungous whenever I see it, and the facade so beautiful that it hasn’t started to feel real, not even after so long. Among the cravings I have felt for Florence in the first weeks of separation—cravings for watermelon granita, Cellini’s statue of Perseus and long walks between historic facades—the most acute has been for a view: the view up from the square into the little office in the Palazzo Vecchio where Machiavelli worked.

You may have noticed that I appended the tag “S.P.Q.F.” to every post this year. It has been my title for the year-in-Florence chapter of my activities, and in explaining why I find it such a fitting title I am at last going to answer formally here one of my favorite questions. It’s my habit in Florence to strike up conversation with random passing tourists, and as one thing leads to another (and often to pizza, gelato and the Uffizi) there are various questions I am often asked by people who discover they have a chance to talk to a real live Renaissance scholar. “Why did they make all this art?” is a common one. Also “Does the Vatican Library really look like it does in Dan Brown?” (that’ll be another day’s post), but the one which I am always happiest to get, and which I get delightfully often, is “So, why is Machiavelli really so important?” Now, I read The Prince in school, and remembered ideas including the stock “It is better to be feared than loved,” and “The ends justify the means,” but I also remember having no idea then why Machiavelli was a big name. I’m pretty sure my teacher didn’t really know either. In fact, most introductions to the works of Machiavelli that I’ve read didn’t even manage to make it clear. After ten years as a specialist in the Renaissance, I think I can finally explain why.

I cannot, however, explain everything at once. There’s too much to do it well. I will therefore divide it into three parts. Doing so is easy, because Machiavelli made two big, big breakthroughs. If I treat each in turn, with the proper historical context, I think I can make Machiavelli make sense.

- Machiavelli, founder of Modern Political Science and History.

- Machiavelli, founder of Utilitarianism/Consequentialist ethics.

The latter issue is where Machiavelli picks up such titles as Arch-Heretic, Anti-Pope, and Destroyer of Italy (also father of modern cultural analysis and religious studies). The former, however, is even more universal in its penetration into modern thought.

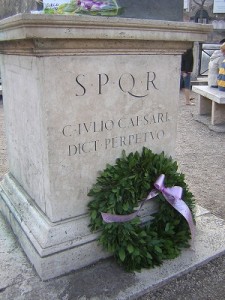

Many are familiar with S.P.Q.R. (Senatus Populus que Romanus, i.e. the Senate and the People of Rome). This is the symbol and slogan of the city of Rome, and has been from the ancient Republic to today. One finds it on stone inscriptions, modern storm drains, grand coats of arms, sun-bleached baseball caps, tattoos, always as a symbol of pride in the continuity of the Roman people and their republican heart. For we who learn in middle school to place the fall of the Empire in 410 or 434 AD, and the end of the Roman Republic in 27 BC when Augustus became Emperor, it is hard to remember that the Senate and other offices of the Republic continued to exist. They existed under the Caesars. They existed in strange forms under the Goths who replaced the Caesars. There were some struggles in the 550s, but even after the 600s, when we think the political Senate probably ceased to exist, there were still important families referred to as Senators. New senates were periodically reintroduced (the Republic had a big moment in 1144) but even when there wasn’t a Senate, the popes who ruled Medieval and Renaissance Rome had to maintain a careful, wary balance with the Roman mob and the powerful Roman “senatorial” families, who sincerely believed they were descendants of ancient Roman senators. Thus, while S.P.Q.R. is the symbol of the Roman Republic, in a long-term sense it represents more Roman pride in self-government as an idea, whether that self-government operates as it did in the Republic through popular election of Senators from among the members of a select group of oligarchical ruling families, or as it did in much of Christian Rome; by securing minimal concessions from the popes through the ability of the Roman city populace and its wealthy lead families to riot, prevent riots, stop invaders, aid invaders, supply funds, refuse to supply funds, and in crisis moments generally be of great aid or great harm to the pontiff and his forces.

S.P.Q.R. represents civic pride so deeply that, counter-intuitive as it may seem, many other cities picked it up. London occasionally used to use S.P.Q.L., and one may read S.P.Q.S. on the shield above the door of the civic museum of the miniscule one-gelateria town of Sassoferrato. And so, I have chosen S.P.Q.F. as the slogan for my year in Florence. “But none of those cities have a Senate!” you may object. Neither, sometimes, did Rome, but it always had a Senate in spirit, and so did these other cities who, by adopting S.P.Q.*. proclaim that they love their city as much as Romans love Rome.

Petrarch, father of Renaissance humanism, desperately wanted Florentines to love Florence as much as Romans had loved Rome, the ancient Romans that he read about in mangled copies of copies of copies of the beautiful, alien Latin of a lost world. He read of the Consul Lucius Junius Brutus who ordered the execution of his own sons when they conspired against the Republic, while at the same time Florence was hiring noblemen from other cities to enforce her laws, and equipping these mercenary magistrates with a private fortress within the city walls (the Bargello) so they could endure siege when they arrested members of powerful Florentine families, and the families attacked to try to liberate their own. He read of the golden peace forged by Augustus, even as rival Florentine families used meaningless factions like the Guelphs and Ghibbelines as excuses to make bloody civil war within the city’s walls. He read of hero after hero who sacrificed their lives for Rome, as families took turns coming to power and persecuting or exiling their rivals, mingling grudges with politics in wholly selfish ways. Petrarch himself grew up in France because his father had been exiled in the squabbles between Black Guelphs and White Guelphs, and had gone to seek work in Avignon, where the French king had carried off the papacy because Rome and her neighbors were too weak to defend the capital from what had once been her own colony. He was born in exile, as he put it, an exile in time as well as place, for his home should have been, not fractious Italy, but glorious Rome, and his neighbors Seneca and Cicero.

The solution Petrarch proposed to what he saw as the fallen state of “my Italy” was to reconstruct the education of the ancient Romans. If the next generation of Florentine and, more broadly, Italian leaders grew up reading Cicero and Caesar, the Roman blood within them might become noble again, and they too might be more loyal to the people than to their families, love Truth more than power, and in short love their cities as the Romans loved Rome. Such men would, he hoped, be brave and loyal in strengthening and defending their homelands. Rome started as one city, and did not make itself master of the world without citizens willing to die for it.

(Yes, I am going to talk about Machiavelli, and I hope you see here that the fundamental mistake most introductions to Machiavelli make is that they start by talking about Machiavelli. Context is everything.)

“Petrarch says we can become as great as the ancients by studying their ways! Let’s do it!” Petrarch’s call went out and, with amazing speed, Italy listened. Desperate, war-torn city states like Florence who hungered for stability poured money into assembling the libraries which might make the next generation more reliable. Wealthy families who wanted their sons to be princely and charismatic like Caesar had them read what Caesar read. Italy’s numerous tyrants and newly-risen, not-at-all-legitimate dukes and counts filled their courts and houses and public self-presentation with Roman objects and images, to equate themselves with the authority, stability, competence and legitimacy of the Emperors. No one took this plan more to heart than Petrarch’s beloved Florentine republic, and, within it, the Medici, who crammed their palaces with classical and neoclassical art, and with the education of Lorenzo succeeded in producing a classically-educated scion who was more princely than princes.

And we’re off! Fountains! Busts! Triumphal arches! Equestrian bronzes! Romanesque loggias! Linear perspective! Mythological frescoes! Confusing carnival floats covered with allegorical ladies! Latin! Greek! Plato! Galen! Geometry! Rhetoric! Navigation! Printing! Libraries! Anatomy! Grottoes! Syncretism! Philosopher princes! Ninja Turtles! Neo-Stoic political maxims! Neo-Platonic love letters! Lyre-playing! Theurgic soul projection! Symposia hosted by Lorenzo de Medici where philosophers and theologians lounge about discussing theodicy and the nature of the Highest Good! All that stuff that makes the Renaissance so exciting!

And we’re off! Fountains! Busts! Triumphal arches! Equestrian bronzes! Romanesque loggias! Linear perspective! Mythological frescoes! Confusing carnival floats covered with allegorical ladies! Latin! Greek! Plato! Galen! Geometry! Rhetoric! Navigation! Printing! Libraries! Anatomy! Grottoes! Syncretism! Philosopher princes! Ninja Turtles! Neo-Stoic political maxims! Neo-Platonic love letters! Lyre-playing! Theurgic soul projection! Symposia hosted by Lorenzo de Medici where philosophers and theologians lounge about discussing theodicy and the nature of the Highest Good! All that stuff that makes the Renaissance so exciting!

In 1506 the Florentine Captain General Ercole Bentivoglio wrote to Machiavelli encouraging him to finish his aborted History of Florence because, in his words, “without a good history of these times, future generations will never believe how bad it was, and they will never forgive us for losing so much so quickly.”

Yes, this is the same Renaissance.

The flowering peak, as we see it, when Raphael and Michelangelo and Leonardo were working away, when the libraries were multiplying, and cathedrals rising which are still too stunning for the modern eye to believe when we stand in front of them, this was such a dark time to be alive that the primary subject of Machiavelli’s correspondence, just like the subject of Petrarch’s 150 years before, was the desperate struggle for survival.

Let us zoom both in and out, for a moment, and take stock of Florence’s situation in the world of Europe as the 1400s close. Florence is one of the five most populous cities in the European world, well… four, now that Constantinople has fallen (1453). Its population is near 100,000, and it rules a large area of farmland and countryside and several smaller nearby cities. It is also one of the wealthiest cities in the world, thanks to the vast private fortunes of its numerous wealthy merchants and banking families, of whom the Medici are but the wealthiest of many. We live in an era before standing armies, but Florence has a force of soldiers for enforcing law, and some modest mercenary armies which it hires.

Who else exists? There is France, the most populous kingdom in Europe, with vast wealth, a population of millions to sustain enormous armies, and Europe’s most powerful king. There are the Spanish kingdoms of Aragon and Castille, with vast naval resources, entering the final stages of merging their crowns into what will soon be Spain. There is the Holy Roman Empire, a complex confederation of semi-independent sub-kingdoms under an elected-but-traditionally-hereditary Emperor who is also ruler of Italy in name, though not in practical terms. There are other kingdoms with ambitious kings and powerful navies: England, Portugal. There is the mysterious and terrifying Ottoman Empire to the East which has made great inroads in the Balkans and Africa. There are the two peculiar and impregnable powers of Europe: Venice with its modest land empire but huge sea empire of port cities and coastal fortresses which pepper the Eastern Mediterranean much farther out than any other Christian force dares go; and the Swiss who live untouchable between their Alps and base their economy almost entirely on renting out their armies as mercenaries to whoever has the funds to hire what everyone acknowledges are the finest troops on the continent. With the sole exception of the Swiss, all these powers want more territory, and there is no territory juicier than Italy, with its fat, rich little citystates, booming with industry, glittering with banker’s gold, situated on rich agricultural fields, and with tiny, tiny populations capable of mustering only tiny, tiny armies. The southern half of Italy has already fallen to the French… no wait, the Spanish… no, it’s the French again… no, the Spanish. The north is next.

That’s how bad it was. That’s why there was such a great flourishing of art and literature and philosophy and invention; because in desperate times people try desperate things to stay alive, and if art, philosophy and cunning are one’s only weapons, one hones one’s art, philosophy and cunning. And that’s why we needed a good historian.

That’s how bad it was. That’s why there was such a great flourishing of art and literature and philosophy and invention; because in desperate times people try desperate things to stay alive, and if art, philosophy and cunning are one’s only weapons, one hones one’s art, philosophy and cunning. And that’s why we needed a good historian.

1492. Lorenzo de Medici, the philosopher quasi-prince, dies, leaving the Medici family resources and effective rule of Florence to his 20-year-old son Piero. Roderigo Borgia is elected Pope Alexander VI, handing control of Rome to the Borgias. Also, some guy called Christopher finds some continent somewhere.

1494. The French invade Italy. This can be partly blamed on Borgias, partly on members of the Sforza family squabbling with each other over who will rule Milan, but France, and every other major power in Europe, had been hungry for Northern Italy for ages.

Now is the moment for young Piero, Lorenzo’s successor, educated by the greatest humanists in the world with the reading list that produced Brutus and Cicero, to marshal his family’s wealth and stand bravely before the enemy. Piero… runs away. Not a high point for Petrarch’s idea of instilling virtue and good leadership through classical education.

In the absence of the Medici, Florence’s republic went through some twists (i.e. Savonarola) and managed to persuade the French not to destroy them through sheer force of argument (again Savonarola), and in 1498 (by removing Savonarola) reverted again to mostly actually being the republic it had consistently insisted it still was all this time. S.P.Q.F.

This, now, was Machiavelli’s job when he worked in that little office in the Palazzo Vecchio:

- Goal: Prevent Florence from being conquered by any of 10+ different incredibly enormous foreign powers.

- Resources: 100 bags of gold, 4 sheep, 1 wood, lots of books and a bust of Caesar.

- Go!

“Desperation” does not begin to cover it. There are armies rampaging through Italy expelling dukes and redrawing borders. Machiavelli is an educated man. He has read all the ancients, all the histories, all the moral maxims and manuals of government. He negotiates. He makes alliances. He plays the charisma card. We’re Florence: we have all the art, all the artists, all the books; you don’t want to destroy us, you want to be our ally. When that fails, there is the bribery card. We can’t defeat you, France, but we can give you 100 bags of gold to use to fund your wars against other people if you attack them instead. Machiavelli negotiates alliances with France. He negotiates alliances with Cesare Borgia. He negotiates anything he has to. He tries to create an army of citizen soldiers who will not, as mercenaries do, abandon the field when things are against them because they have no incentive to die for someone else as citizens do for their families and fatherland (the Senate and the People of Florence!)

1503. The Borgias fall (a delightful story, for another day). The bellicose and crafty Pope Julius II comes to power.

1508. The Italian territories destabilized by the Borgias are ripe for conquest. Everyone in Europe wants to go to war with everyone else and Italy will be the biggest battlefield. Machaivelli’s job now is to figure out who to ally with, and who to bribe. If he can’t predict the sides there’s no way to know where Florence should commit its precious resources. How will it fall out? Will Tudor claims on the French throne drive England to ally with Spain against France? Or will French and Spanish rival claims to Southern Italy lead France to recruit England against the houses of Aragon and Habsburg? Will the Holy Roman Emperor try to seize Milan from the French? Will the Ottomans ally with France to seize and divide the Spanish holdings in the Mediterranean? Will the Swiss finally wake up and notice that they have all the best armies in Europe and could conquer whatever the heck they wanted if they tried? (Seriously, Machiavelli spends a lot of time worrying about this possibility.) All the ambassadors from the great kingdoms and empires meet, and Machiavelli spends frantic months exchanging letters with colleagues evaluating the psychology of every prince, what each has to gain, to lose, to prove. He comes up with several probable scenarios and begins preparations. At last a courier rushes in with the news. The day has come. The alliance has formed. It is: everyone joins forces to attack Venice.

O_O ????????

Conclusion: must invent Modern Political Science.

I am being only slightly facetious. The War of the League of Cambrai is the least comprehensible war I’ve ever studied. Everyone switches sides at least twice, and what begins with the pope calling on everyone to attack Venice ends with Venice defending the pope against everyone. Between this and the equally bizarre and unpredictable events which had dominated the era of the Borgia papacy and pope Julius’ rise to power (another day, I promise!) Machiavelli was left with the conclusion that the current methods they had for thinking about history and politics were simply not sufficient.

Machiavelli did not, however, stop immediately and start working on the grand treatises and new historical method he would hand down to posterity. He had a job to do, and wasn’t concerned with posterity—or rather he was, but with a very specific posterity: the posterity of Florence. S.P.Q.F.

1512. The Medici family returns, armed with new allies and mercenaries, and takes Florence by force. The Pallazzo Vecchio, seat of the Signoria, heart of the city, is converted into the Ducal palace. Machiavelli is expelled from government and, after a little while, is (falsely) accused of plotting against the Medici, arrested, tortured and banished.

Now, after the grand and fast-paced life of high politics, after being ambassador to France, after walking with princes, Machiavelli finds himself at a farm doing nothing. He describes in a letter his weary days, taking long walks through fields and catching larks, retiring to a pub to listen to the petty babble of his rustic neighbors. At the end of a wasted day, he says, he returns each evening to his little cottage, there strips away the dirt and ragged day clothes of his new existence, and puts on the finery of court. Thus attired, ready to negotiate with kings and popes, he enters his library, there to spend the evenings in commerce with the ancients.

And he starts writing his “little book on princes.”

Now, everyone who’s anyone is banished from Florence at some point. Dante, Petrarch, Cosimo de Medici, Benvenuto Cellini like five times… When one is banished, one is often banished to some spot in the countryside outside Florence, which is what happened in this case. The terms, generally, are that if you’re good and stay there then they’ll think about someday calling you back, but if you run off to some other city they make your banishment a bit more permanent. Machiavelli is expected to run off. He’s a talented and experienced political agent, a great scholar, author and playwright. He could get a job in Rome for the pope or a Cardinal, in Naples, in Paris, in a dozen Italian citystates, in the Empire. He doesn’t. He doesn’t even try.

Machiavelli only works for Florence. S.P.Q.F.

Machiavelli only works for Florence. S.P.Q.F.

What he does do is everything in his power to get the Medici to hire him. “The Medici? Didn’t they destroy his precious republic? Didn’t they expel him? Didn’t they torture him?” Yes, but that doesn’t matter. What matters is that they rule Florence, and whoever rules Florence must be strong. History shows that, when there is a regime change, there is civil war and people die. When Florence has a regime change, Florentines die, and non-Florentines have a good chance of stepping in for conquest. The Prince is a manual for staying in power. Machiavelli writes it for the Medici, hoping it will secure him a job so he can get back where he should be, working for Florence’s safety from the inside. But it also explains his conclusions from all this dark experience.

History should be studied, NOT as a series of moral maxims intended to rear good statesmen by simply saturating them with stories about past good rulers and hoping they become virtuous by osmosis. History should be studied for what it tells us about the background and origins of our present, and past events should be analyzed as a set of examples, to be compared to present circumstances to help plan actions and predict their consequences. Only this way can disasters like the Borgia papacy, the French invasion and the War of the League of Cambrai be anticipated and avoided. What worked? What didn’t? What special characteristics of different times and places have led to success and failure?

This is modern Political Science. It is how we all think about history now, and the way it is approached in every classroom. We are, in this sense, all Machiavellian.

Of course, that is not what the word Machiavellian means. The new system of ethics Machiavelli introduces in his manual to keep the Medici in power is deservedly recognized as one of the most radical, dangerous and potentially destructive moves in the history of philosophy, and one of the most far-reaching. We are used to the trite summary “the end justifies the means,” and all the terrible, villanous things which that phrase has justified. But Machiavelli’s formula is not in any way villanous, nor was he. I will need another day to fully explain what that phrase means, but in a micro-summary, yes, Machiavelli did argue that the end justifies the means, and yes, he did mean it, but in his formulation “the end” was limited to one and only one very specific thing: the survival of the people under a government’s protection. Or even more specifically, the survival of Florence. That cathedral, those lively alleyways, those sculptures, that poetry, that philosophy, that ambition. S.P.Q.F.

Do you ever play the game where you imagine sending a message back in time to some historical figure to tell him/her one thing you really, really wish they could have known? To tell Galileo everyone agrees that he was right; to tell Schwarzschild that we’ve found Black Holes; to tell Socrates we still have Socratic dialogs even after 2,300 years? I used to find it hard to figure out what to tell Machiavelli. That his name became a synonym for evil across the world? That the Florentine republic never returned? That children in unimagined continents read his works in order to understand the minds of tyrants? That his ideas are now central to the statecraft of a hundred nations which, to him, do not yet even exist?

But now I know what I would say:

But now I know what I would say:

“Florence is on the UNESCO international list of places so precious to all the human race that all the powers of the Earth have agreed never to attack or harm them, and to protect them with all the resources at our command.”

He would cry. I know he would. It’s the only thing he ever really wanted. When I think about that, how much it would mean to him, and pass his window in the Pallazzo Vecchio which he spent so many years desperate to return to, I cry too.

Machiavelli definitely loved Florence as much as the Romans loved Rome, and worked to protect it as much as Brutus or Cicero. Florence also deserved to be loved that much. It deserves its S.P.Q.F. I’ve had, not just this year, but several earlier opportunities to get to know Florence in person, and even more years to read deeply into Florentine history and really understand all the invaluable contributions this city has made to the world. I could never call myself a Florentine, but I do believe I am now someone who understands why Florence deserves to be loved that much by her people, why Florence deserved Machiavelli, and his efforts, and all the efforts of the other great figures—Dante, Petrarch, Ficino, Bruni, Brunelleschi, Cosimo and Lorenzo de Medici—who worked so hard to save it—through art, philosophy and guile—from the destruction that always loomed. I know why it deserves UNESCO’s recognition too. It makes it a hard home to leave.

See next, Machiavelli I.5, Thoughts on Presenting this Style of History, then Machiavelli II: the Three Branches of Ethics

57 Responses to “Machiavelli I – S.P.Q.F. (Begins Machiavelli Series)”

-

The conclusion of this post brought tears to my eyes as well.

-

I agree, but the conclusion comes to quickly. The first 8 paragraphs are spent giving context, before Machiavelli is even mentioned. Then we get into Florence, the Medici and the other players. We never really get a sense of who Machiavelli was or what all he did, just his intentions to preserve his precious Florence at all costs. What all did he do to achieve those intentions? Did he not plot against the Medici once they returned to power, or was that conspiracy a lie crafted by the Medici who feared him and felt they could never trust him? If so, why? Did they feel like he betrayed them after they fell from power?

Clearly the heads of the Medici family did not trust him, and they had no intention of giving him any political position that he could then use to hatch a conspiracy against them. “They” primarily being Giulio di Giuliano de’ Medici and Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici, aka Popes Leo X and Clement VII. They were doing just fine for themselves, they didn’t need him. Giving him any sort of power would only open the door to their own demise.

How died Machiavelli even die? He lived all throughout the years that the Medici had firm control, but once that control was lost in 1527, and Rome was sacked, Machiavelli dies during this crucial moment where the Medici are losing complete control. They read Machiavelli his last rites and killed him before he could help throw them out, and keep them out of Florence. All “The Prince” did was further convince the Medici he was too dangerous. If Machiavelli had lived, the Medici probably would not have returned to power 3 years latter with the help of Emperor Charles V. Machiavelli would have convinced Charles V it would be more beneficial to him to not have the Medici return to power in Florence.

I love history. It isn’t written in stone like people tend to think.

Did King Henry VIII really die of gout, or is it possible he was poisoned by the newly formed Jesuit Order? The Jesuits were created to be the Vatican’s spear against the Reformation after all, and they are students in Machiavelli’s “the end justifies the meas” philosophy. Were King Henry’s last words of “Monks! Monks! Monks!” really a call for a last minute confession, or was he naming his assassins? There were so many plots, conspiracies and accusations of conspiracies it’s sometimes difficult to know how some things happened and why, especially when the plotters and conspirators didn’t want anyone to know the “who” or the “why”.

-

-

Me too.

And this is the best thing about Macchiavelli I have ever read.

Petrarch wasn’t wrong. I mean he did correctly identify civitas as the significant thing. I’ve been saying this for years.

You know the thing about tyranny never lasting three generations, which they also say about money in families? Thinking about Piero, I wonder if that’s a thing about everything. You can bring up your heir to be Lorenzo, but he can’t ever bring up his heir that way. (I know Lorenzo was actually Cosimo’s grandson, but.) It’s a problem with primogeniture above everything. People are going to have families and people are going to be nepotistic towards their families, look at the powerful political dynasties of nominally democratic India and the US. Unless you say that nobody with a relative in power is eligible, it’s going to happen. Venice did surprisingly well with this over a surprisingly long time.

Oh, and The UN or the associated civility of the Anglosphere or something should provide a grant for you to live in Florence always and do visitor outreach and write.

-

Oh, and the other thing I was going to say is that in addition to France and the HRE and the Swiss and all of that, everything from the fall of Constantinople to Lepanto is shadowed with the fear that the Turks would be inevitably coming, by and by.

-

Yes. I will discuss the Turks more when I get into Borgia goodies. And Petrarch was definitely not wrong – Lorenzo proved that. Petrarch just needed a more nuanced follow-up.

I agree about the third-generation issue with Piero. It is a conspicuous pattern. Now, do we read Machiavelli here as a 3rd generation Petrarchan humanist?

-

What a fabulous discussion of Machiavelli! I knew most of those things individually but not this whole picture, and I love it.

-

It took me several days to sit down and read this entry, but I’m so happy I did–it’s a wonderful piece of work.

-

This was fascinating and absolutely brilliant. I certainly can’t wait to read your thoughts about the Borgias and the War of the League of Cambrai. I have had an interest in the Borgias ever since reading The March of Folly, and as a budding military historian, the War of the League of Cambrai is amazingly interesting.

i would point out another victory of Machiavelli to my mind. I would think that one of Machiavelli’s goals was to spread his ideas and advice on power and ruling. When politics denied him this power, he turned to books; by converting readers to his cause, they would unwittingly spread his ideas. Even those who who would be horrified by his radical methods and ideas would spread his ideas by telling people to avoid them. And objection to these extremist ideals should keep aggression to a lesser level.

As Robert Greene wrote: “Over the centuries millions upon millions of readers have used Machiavelli’s books for invaluable advice on power. But could it possibly be the opposite – that it is Machiavelli who has been using his readers? Scattered through his writings and through his letters to his friends, some of them uncovered centuries after his death, are signs that he pondered deeply the strategy of writing itself and the power he could wield after his death by infiltrating his ideas indirectly and deeply into his reader’s minds.” -

Beautiful writing. You hit all the right notes and do so with such eloquence. Can’t wait for the next installment. I recently gave a TED talk about Machiavelli that hits some similar notes WRT my graphic novel biography of him. You might find it interesting: http://tedxboston.org/speaker/

Don

-

Sorry, screwed up that link: http://tedxboston.org/speaker/macdonald

-

Yes, Don, I saw some of the preliminary info about your comic biography a year ago and have been following it with great interest ever since. Exciting to see it fruit!

-

-

That was beautiful and useful.

-

This is a wonderful piece.

I read Machiavelli’s political works as being about two related problems: how to found and how to maintain a free state, and, more broadly, how to turn that free state into a free nation. The free state, in the first instance, is obviously Florence, but the free nation is Italy, and his call in Chapter 26 of The Prince for the head of the Medici family to liberate Italy is not just a wonderful rhetorical flourish, it is a powerful call to all lovers of freedom. Not only in Italy, Machiavelli is very much the father of republican nationalism, and the Discourses I read as being about how to construct a stable republic once the nation has been freed.

It is astonishing how much of the language of politics we owe to Machiavelli, including the word “state” itself.

-

Yup

-

-

A wonderful piece of writing.

-

Holy cow, why isn’t more history taught like this?

-

*applause*

-

This is a beautiful discussion.

-

John Evans, above, has it exactly right – I have never had any interest in history (except for some specific subjects, like cooking), simply because, when I was at school fifty-odd years ago, history was made so damned boring (I excelled in exams, but it otherwise failed utterly to engage my interest).

Reading this has been inspiring.

-

It wasn’t so much the recommendations for ruthlessness and bold lies that brought hatred down on Machiavelli’s head, it was that he did not wrap them in appeals for the Greater Glory of God.

He deserves credit for a third major innovation: unapologetic secularism and “humanism” in the sense of thinking and acting in the real world without concern for supernatural rules or entities.

-

Good comments indeed. You’ve made me realize I need to devote a full entry to Machaivelli and religion, which is often the least understood aspect of his rarely-understood work.

-

-

I adore Florence and it was my destination when first I went to Europe. I’d dreamed of going there for more than 30 years and – exhausted from the trip – I wept when I first saw Duomo.

Just one detail about Duomo: while the church was started in 1296 and completed *structurally* in 1469 with the placing of Verrochio’s copper ball atop the lantern. However, the original façade was only completed in its lower portion and then left unfinished. It was dismantled in 1587-1588 by the Medici court architect Bernardo Buontalenti and was left bare – i.e. plain bricks, just as San Lorenzo appears now – until the 19th century.

Work began in 1876 and completed in 1887. This neo-gothic façade in white, green and red marble forms a harmonious entity with the cathedral, Giotto’s bell tower and the Baptistery, but some think it is excessively decorated.-

The Museo del Opera del Duomo has pieces of the original unfinished 1587 facade, and the museum is about to be rebuilt in order to situate them in a full-sized wooden reconstruction of the original front of the cathedral, so we’ll be able to see first hand what they looked like in situ before they were removed and, eventually, replaced by the 19th century facade. I can’t wait to see it.

-

-

Jo, the point about 3 generations is broadly true, hence the need for institution building. The Romans tried to use adoption to ensure succession, and the papacy endured as a power for so long by their succession model, enabling them to survive the odd Borgia.

I was struck by this institutional resilience most recently when visiting Cambridge University with my son, and the explicitness of their recruitment policies “you need to pass exams and be able to hold interested intellectual conversations about your chosen subject” – as they’re recruiting undergraduates to converse with weekly for 3 years.

The reason Cambridge has lasted 800 years is being good at this, and at convincing people to fund it. -

Thank you for this fascinating account of Machiavelli. Very nicely written.

I recently finished reading The House of Medicis by Hibbert (http://www.amazon.com/House-Medici-Its-Rise-Fall/dp/0688053394/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1343766901&sr=1-1&keywords=medici) and Defenders of the Faith (http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B002XULWNO/ref=s9_simh_gw_p14_d5_i2?pf_rd_m=ATVPDKIKX0DER&pf_rd_s=center-2&pf_rd_r=19FYVHNHVWYASJJ94KHT&pf_rd_t=101&pf_rd_p=470938631&pf_rd_i=507846)

both books are fascinating and explain the background of 1400s Florence and the politics of the time. Highly recommend these 2 works.

-

If I could send a message back in time to Machiavelli I’d probably send him designs for a steam engine, or something like that. I’m not going to waste my chance to change the world on making one guy cry.

-

The limit of this particular thought experiment is giving someone a piece of satisfying knowledge, not history-altering. If we’re talking history-altering, the best in my view is to teach the germ theory of contagion and basic sanitation practices to the earliest civilization capable of implementing them, probably Mesopotamia.

-

-

If you haven’t already, you might want to also read “Fortune Is A River”, which covers Machiavelli and Leonardo Da Vinci’s one enterprise together … leading a project to build a canal to pypass Pisa. The calamatous failure of the project also helps explain why both of them were a little sour on democracy.

-

Florentine Ninja Turtles?

Awesome essay, can’t wait for more. And where’s the tip jar?

-

Hm… I hadn’t thought about a tip jar. Perhaps I might set up an Amazon associates page, so I can direct people to recommended history books, and get a few cents kickback? Does that appeal to anyone? If so I’ll set it up, since I certainly have recommendations of further reading to share.

More Machiavelli soon. I try to do an entry every 2 weeks, and will do my best to keep up with it.

-

-

I am hoping that you will write something about Principessa Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici and her extraordinary sense of responsibility as the last of the Medici. Were it not for her bold vision we should not know Florence as it is today. Please? Please?

-

Just wanted to say thank you – ever since reading “Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong” I’ve been looking for more examples of history with the context in, and your post (recommended by a friend) is a wonderful specimen. The passion you have for Italy and Florence especially comes through just beautifully – I teared up at the end too! I would absolutely come back for future lessons. 🙂

-

[…] that explicitly lacks anything supernatural. I trust the astonishing historian Ada Palmer (who makes people cry with Renaissance History) when she suggests that in this regard, at the turn from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance, De […]

-

[…] you have not already read it, see my Machiavelli Series for historical background on the Borgias. For similar analysis of TV and history, I also highly […]

-

[…] also the earlier chapers of this series: Machiavelli Part I: S.P.Q.F., Part I addendum, and Part II: The Three Branches of […]

-

[…] is the last entry in my Machaivelli series. See also Machiavelli Part I, Part I.5, Part II, Part III and Part […]

-

Beautiful.

Though you would, sadly, be lying a bit to Machiavelli… because there are *still* powerful governments who do *not* respect places on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Saudi Arabia and Israel are the most famous, but they’re not the only ones.

-

Very interesting read.. Thanks

-

[…] how Beccaria persuaded Europe to discontinue torture, how Petrarch sparked the Renaissance, how Machiavelli gave us so much. Histories of agents, of people who changed the world. Such histories are absolutely […]

-

I wanted to tell you how much I have enjoyed your writing at this site. The Borgia comparison and Machiavelli I (still reading the rest) are wonderfully fascinating. What a joy it is to have such a talented and knowledgable person share their talents so that others might enjoy them. Great art, whether visual arts, music or in this case, fine writing has the capacity to lift us up from the everyday into the sublime bringing much joy and allowing reprieve from the daily cares of life. Having no artistic talent myself, I truly appreciate those that share their talent. The book suggestions on Amazon would be a great resource. Finally, if you lecture as well as you write, you would be great doing a lecture series for The Great Courses, in my humble opinion. Reading the discussions here have been enlightening, and very enjoyable. Thanks to all.

-

Fascinating look at Machiavelli and at the origins of modern thought. I knew there was a reason we kept historians around, thanks! ^_^

-

[…] qu’avant d’écrire ses plus grand classiques, Machiavel travaillait pour l’État. Coincé dans un minuscule bureau, il devait défendre sa petite république florentine chérie dans un monde hostile. […]

-

[…] suggested I check out a thread of postings on web site by an author and scholar, starting with this on Ex Urbe. As was predicted I was strongly ambivalent about it. The series presents a view of […]

-

This post has inspired me to add SPQV (for Vancouver) to my email signature

-

[…] Some background on Machiavelli — this is good reading before listening to the podcast, or even after the podcast if you want more info on that guy. […]

-

[…] Some background on Machiavelli — this is good reading before listening to the podcast, or even after the podcast if you want more info on that guy. […]

-

I began reading this weeks ago and only now did I get around to finishing and I am really glad that I did. Didn’t know that bit about UNESCO and Florence either.

S.P. Q.F

-

[…] People living in the European and Mediterranean Middle Ages generally (oversimplification) divided history into two parts, BC and AD, before the birth of Jesus and after. For finer grain, you used reigns of emperors or kings, or special era names from your own region, i.e. before or after a particular event, rise, reign, or fall. There was also a range of traditions subdividing further, such as Augustine’s six ages of the world which divided up biblical eras (Adam to Noah, Noah to Abraham, etc.), though most of those subdivisions are pre-historical, without further subdivision post Christ’s Incarnation. The Middle Ages also had a sense of the Roman Empire as a phase in history, but it was tied in with the BC-to-AD tradition, and with ideas of Providence and a divine Plan. Rome had not only Christianized the Mediterranean and Europe through the conversation of Constantine c. 312 CE, but authors like Dante stressed how the Empire had been the legal authority which executed Christ, God’s tool in enacting the Plan, as vital to humanity’s salvation as the nails or the cross. Additionally, many Medieval interpreters viewed history itself as a didactic tool, designed by God for human moral education (not the discipline of history, the actual events). In this interpretation of history, God determined everything that happens, as the author of a story determines what happens. The events of the past and life were like the edifying pageant plays one saw at festivals: God the Scriptwriter introduces characters in turn—a king, a fool, a villain, a saint—and as we see their fates we learn valuable lessons about fickle Fortune, hypocrisy, the retribution that awaits the wicked, and the rewards beyond the trials and sufferings of the good. The Roman Empire had been sent onto the world’s stage just the same, a tool to teach humanity about power, authority, imperial majesty, law, justice, peace, offering a model of supreme power which people could use to imagine God’s power, and many other details excitedly explored by numerous Medieval interpreters. (Many Renaissance interpreters still view history this way, and the first who really doesn’t do it at all is Machiavelli.) […]

-

Thanks! I loved reading that. I hope to one day visit Florence myself to find out for myself and see with my own eyes what Machaivelli loved about.

-

[…] People living in the European and Mediterranean Middle Ages generally (oversimplification) divided history into two parts, BC and AD, before the birth of Jesus and after. For finer grain, you used reigns of emperors or kings, or special era names from your own region, i.e. before or after a particular event, rise, reign, or fall. There was also a range of traditions subdividing further, such as Augustine’s six ages of the world which divided up biblical eras (Adam to Noah, Noah to Abraham, etc.), though most of those subdivisions are pre-historical, without further subdivision post Christ’s Incarnation. The Middle Ages also had a sense of the Roman Empire as a phase in history, but it was tied in with the BC-to-AD tradition, and with ideas of Providence and a divine Plan. Rome had not only Christianized the Mediterranean and Europe through the conversion of Constantine c. 312 CE, but authors like Dante stressed how the Empire had been the legal authority which executed Christ, God’s tool in enacting the Plan, as vital to humanity’s salvation as the nails or the cross. Additionally, many Medieval interpreters viewed history itself as a didactic tool, designed by God for human moral education (not the discipline of history, the actual events). In this interpretation of history, God determined everything that happens, as the author of a story determines what happens. The events of the past and life were like the edifying pageant plays one saw at festivals: God the Scriptwriter introduces characters in turn—a king, a fool, a villain, a saint—and as we see their fates we learn valuable lessons about fickle Fortune, hypocrisy, the retribution that awaits the wicked, and the rewards beyond the trials and sufferings of the good. The Roman Empire had been sent onto the world’s stage just the same, a tool to teach humanity about power, authority, imperial majesty, law, justice, peace, offering a model of supreme power which people could use to imagine God’s power, and many other details excitedly explored by numerous Medieval interpreters. (Many Renaissance interpreters still view history this way, and the first who really doesn’t do it at all is Machiavelli.) […]

-

Thank you very much, fascinating text! But…

“Florence is on the UNESCO international list of places so precious to all the human race that all the powers of the Earth have agreed never to attack or harm them, and to protect them with all the resources at our command.”

Alas, Machiavelli was well aware about the true value of such obligations.

-

If Dame Frances Yates is to be believed, some Renaissance thinkers went beyond Classical Rome and Greece to and (almost entirely imaginary) Ancient Egypt for their lost paradise of old.

-

[…] Further Reading: Ada Palmer’s essays on Machiavelli. […]