Machiavelli III: Rise of the Borgias

Once upon a time (circa 1475) the whimsical Will that scripts the Great Scroll of the Cosmos woke up in the morning and decided: Some day centuries from now, when mankind has outgrown the dastardly moustaches of melodrama and moved on to a phase of complex antiheroes, sympathetic villains and moral ambiguity, I want history teachers to be able to stand at the front of the classroom and say, “Yes, he really did go around dressed all in black wearing a mask and killing people for fun.” Thus Cesare Borgia was conceived.

Note: I have discovered that I have a lot to say about the Borgias, so this will be the first of two posts about their impact on Machiavelli. I will try my best to get the second one out promptly. Thank you, kind readers, for being patient with the long delay between the last post and this. It was a chaotic September.

See also the earlier chapers of this series: Machiavelli Part I: S.P.Q.F., Part I addendum, and Part II: The Three Branches of Ethics.

The Handbook of Princes:

In the middle phase of the Harry Potter saga, my father phoned me one day to exclaim that if he were Harry he would walk up to Crabbe and Goyle and appeal to them in the name of rational self-preservation. Voldemort is a terrible, terrible person who randomly kills people who work for him. Joining his side, or becoming involved with him in any way, is absurdly dangerous. If you’re a Malfoy or something, and you know he’d come after you if you tried to quit, then joining him is certainly the safest option. But willingly getting involved is rather like plunging enthusiastically into a game of Russian roulette. I cite this example because its simple appeal to human Reason (Evil is bad! You don’t want to be around it! Think about it!) is exactly the sort of argument which lay at the heart of the Handbook of Princes genre before Machiavelli got his ink-blackened hands on it. The Princewas far from the first Handbook of Princes. To the contrary, it argued against a long tradition of manuals of etiquette and collections of heroic maxims which were a common literary form, especially in an age when authors made money from their books only by dedicating them to patrons, who were often more inclined to reward books which seemed directly useful to themselves and their heirs.

A typical Handbook of Princes consisted of a mixture of anecdotes and advice. The anecdotes were great tales of heroic exploits, focusing on brilliant and successful historical figures (Augustus Caesar, Henry V, take your pick) or on more obscure stories wherein a single figure (usually from Roman history) is remembered for a single noble act. The presentation focuses on the hero, his character and the virtues (courage, wisdom, patience, generosity, self-sacrifice, industry) which enabled his successes. These works are histories/biographies in a sense, but unlike the modern versions of those genres, were largely devoid of cultural and historical context, and would never discuss how men were products of their times, or how their successes were affected by class movements or economics. The men were successes because they were great men, and by reading about their actions and the virtuous decisions which underlay them, the young prince could absorb these virtues and learn to do the same. Moral advice accompanied these moral examples, advice predicated on a combination of logic and the Renaissance universe in which we must remember God is presumed to take a very active part. The virtuous prince will be more successful than the corrupt or wicked one. Why? First, because people will love and respect him, and therefore obey him. If he acts like Voldemort, reason and self-preservation will drive his followers to realize that it is dangerous to be around him, and he will be abandoned and overthrown. Tyrants fall to tyrranicides. Beneficent monarchs, on the other hand, attract loyal followers who want them to stay in power. People living under a good king will be willing to go to effort to keep him in power.

As for dealing with rivals and enemies, i.e. foreign affairs, here too virtue is advised. The virtuous prince will be more successful. Why? Because people will respect and listen to him. Because chivalrous conduct makes a man outstanding and brave. Because a virtuous man will have fewer enemies, at home and abroad, and thus be able to sleep at night with a clear conscience and less fear of assassins. And because God is part of politics in this age. This culture still believes in trial by combat, that the champion of a virtuous and true cause will always defeat the champion of an unjust one. The saints will like and bless the good king, and drive plague from his kingdom. “But bad things happen to good people too!” objects the devil’s advocate. “What about Job? What about the fall of the Roman Empire? What about nuns who get the Black Death tending to people who have the Black Death?” True, the culture answers, sometimes God sends tests to virtuous men, but by persevering through them with virtue one earns even greater rewards. There is Providence. If there is Providence, it is logically never, ever a good idea to do evil. While the ultimate balance lies in Heaven, even on Earth, in a world with a deep belief in saints and direct divine intervention to answer prayer and protect the chosen, virtue is 100% the right call. And religion aside, won’t a prince who is loved be showered with support and help? Certainly Petrarch and his followers, who were so desperate for peace and stability, would eagerly shower any virtuous prince with support and help, and very sincere loyalty. So stands the genre when a young Machiavelli works with Soderini in the Palazzo Vecchio, attempting to run the government of Florence and to achieve stability and peace in a world of chaos and conquest. This government is the product of Florence’s rebellion against Medici corruption, and everyone knows it exists for the sole purpose of protecting and serving the Florentine citizens and protecting the city and all her works and precious people. No one in Florence has any incentive to do anything but love and support this government. Right?

Unmatched in Infamy:

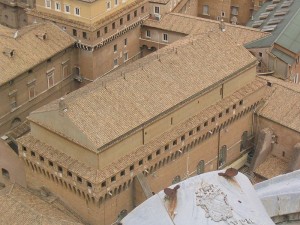

I was in the palace section of the Vatican Museum recently, showing some friends the dark neoclassical frescoes and blue and gilded Borgia bulls which so oppressively dominate Alexander VI’s apartments that no pope has been willing to inhabit that part of the palace since, when a guide came by with her tour group. She was speaking English as a compromise language, since she was a native Italian and her group was Korean, but since they were all 75% fluent in English it sufficed for basic communication. Basic, but not subtle, so when they entered the room she began, “These are the rooms of Pope Alexander VI, he…” and then I saw a look of exasperated despair wash over her face. How with broken English could she communicate the significance of the Borgia papacy to this group to whom Renaissance Italian politics were so foreign that if she’d told them Michelangelo was a pope, or Duke of Florence, or both, they would probably have believed her. “He was a very very, very very, very, very bad pope,” she concluded, and shooed her flock on. I applauded her concision at the time, but when she had moved on my friends immediately turned on me and (with the full pressure of a common language demanding thoroughness) asked, “Why was he so bad? I mean, this is the high Renaissance right before the Reformation – weren’t all the popes incredibly corrupt and terrible? You’ve been telling us stories about catamites and elephants and brothels all day; what made Alexander VI so exceptional?”

I was in the palace section of the Vatican Museum recently, showing some friends the dark neoclassical frescoes and blue and gilded Borgia bulls which so oppressively dominate Alexander VI’s apartments that no pope has been willing to inhabit that part of the palace since, when a guide came by with her tour group. She was speaking English as a compromise language, since she was a native Italian and her group was Korean, but since they were all 75% fluent in English it sufficed for basic communication. Basic, but not subtle, so when they entered the room she began, “These are the rooms of Pope Alexander VI, he…” and then I saw a look of exasperated despair wash over her face. How with broken English could she communicate the significance of the Borgia papacy to this group to whom Renaissance Italian politics were so foreign that if she’d told them Michelangelo was a pope, or Duke of Florence, or both, they would probably have believed her. “He was a very very, very very, very, very bad pope,” she concluded, and shooed her flock on. I applauded her concision at the time, but when she had moved on my friends immediately turned on me and (with the full pressure of a common language demanding thoroughness) asked, “Why was he so bad? I mean, this is the high Renaissance right before the Reformation – weren’t all the popes incredibly corrupt and terrible? You’ve been telling us stories about catamites and elephants and brothels all day; what made Alexander VI so exceptional?”

It is a fair question. The papal throne was indeed at its most politicized at this point, a prize tossed back and forth among various powerful Italian families and the odd foreign king, and Italy remains littered with the opulent palaces built with funds embezzled by families who scored themselves a pope. My best short answer is this:

- They were Spaniards, and the Italians hated that, so all possible tensions were hyper-inflamed.

- Instead of the usual graft and simony, they tried to permanently carve out a personal Borgia duchy in the middle of Italy, and when that was going well, they tried to turn the papacy into a hereditary monarchy.

- They very nearly succeeded.

The Borgia family came from Valencia in eastern Spain (then Aragon), and were powerful enough there to frequently secure Church offices for younger sons, including the bishop’s miter. Trivium of the day: Valencia’s Cathedral is known for possessing one of the best accredited Holy Grails (i.e. more confirmed miracles than any leading rival grail candidate), which means both Rodrigo and Cesare Borgia were briefly custodians of the Holy Grail. The first Borgia pope, Callixtus III(originally Alfonso de Borja, b. 1378, d. 1458), was from Valencia in eastern Spain. During the middle years of his career he was instrumental in getting the royal house of Aragon to accept the compromises which ended the schism, in those years when Europe was going through its antipope-a-month phase. He was made a Cardinal as a reward, came to Rome, and was elected pope in 1455 as a compromise candidate. A compromise pope is elected when two or more powerful rivals have a deadlock in which neither can secure the majority necessary to become pope, and neither will let the other win, so they pick someone neutral and extremely old who is guaranteed to die within a couple years, giving the rivals time to level up their bribery skills and try again. The most notable achievements of his three year reign include a brief crusade, excommunicating Halley’s Comet when its bad luck interfered with his crusade (“Take that! No communion or last rights for you, comet!”), and securing Cardinal’s hats for two of his nephews, including young Rodrigo.

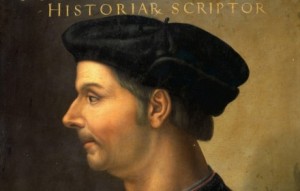

Rodrigo Lanzol Borgia, later Pope Alexander VI (1431-1503) was only matrilineally a Borgia, the son of Callixtus III’s sister. He took a law degree at the university of Bologna, and was twenty-five when his uncle became a compromise pope. Making good use of their manifestly narrow window, Callixtus had the city of Valencia promoted from having Bishops to having Archbishops. He thus made Rodrigo an Archbishop, then a Cardinal, and finally gave him the position of Vice-Chancellor of the Church, an important (and lucrative!) position managing the papal purse, particularly its taxes and military expenditures. There is no better office from which to be plugged directly into the detailed workings of the Church, and to secure a precarious but powerful position as one of the foremost non-Romans in Rome. After his uncle’s death, Rodrigo stayed in this position through four more papacies, setting up a permanent household in Rome and there raising his most famous bastard children. When his fifth papal election rolled around in 1492, he was nicely on track to be another mildly-entertaining, thoroughly-corrupt Renaissance pope. The papal election of 1492 was one of the great power games of world history. Anyone seeking to create a board game or one-shot role-playing simulation of an exciting political moment need look no farther. Twenty-three men are locked in the not-yet-Michelangelized Sistine Chapel. They can’t leave until someone receives twelve votes and becomes pope. Everyone has a different goal. A few want to be pope. Others want to sell their votes to the papabile (pope-able candidates) for the best price going. Some want wealth; some have plenty and want to turn it into power. Some want titles; some have titles but have lost the fortunes that should go with them and are hoping to earn that back. Some are young and want to make friends and be owed favors; some are old and want young relatives to become cardinals to preserve the family’s toehold in the College. The Medici Cardinal is sixteen and hoping to cement the family’s hold on Florence. The Patriarch of Venice is ninety-six, dying, and wants to go back to his impregnable hometown and eat candy. Ten of the cardinals present are nephews of previous popes, eager to keep nursing from the coffers and to keep their family fortunes safe from rivals. Eight are pawns of kings and want to secure the clout necessary to get the new pope to grant their masters’ requests should a king want to, for example, divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boelyn (that’s a few decades off but it’s the kind of thing one has to be prepared for). The previous pope glutted the College with his own relatives but all are too young for anyone to be willing to vote for them, so they have thrown their collective clout behind the cunning veteran Giuliano della Rovere: learned, aggressive, interested in art, interested in the classics, and interested above all in how both can be used as tools of power. As for Rodrigo Borgia, he has waited a long time. This may well be his last shot at his uncle’s throne. Resources: all the wealth, contacts, secrets, tax-returns and dirt he has accumulated in decades managing the papal purse.

It was a very complex election, about which we have lots of information, but little that is reliable. We know there were four rounds of voting, and that Borgia was not one of the front runners in the three leading to his unanimous or near-unanimous victory in the last. We have records of enormous bribes, offices and territories representing tens of thousands of florins in annual income changing hands. Some allege that the king of France contributed hundreds of thousands to efforts to get Giuliano della Rovere on the papal throne. It seems pretty clear that the Borgias smuggled letters offering fat bribes into the chapel inside the food which was delivered for the cardinal’s meals. One delightful anecdote from the period claims that the 96-year-old Patriarch of Venice was the last critical swing vote, who, having a wealthy family, secure lines of power, a literally impregnable homeland, and not long to live to enjoy the fruits of bribery, sold out for a couple hundred florins and some marzipan, since, when one is locked in the Sistine Chapel with a bunch of clerics for day after day, sweets are precious hard to come by. In the end even Giuliano della Rovere himself seems to have accepted that, if he could not win, it was better to profit and wait than to remain stubborn and gain nothing. He was still fit, favored by the King of France, and likely to survive to see another election. (For more nitty-gritty details on what we think we might maybe know could have happened potentially, see the wiki.)

Thus Rodrigo Borgia became Pope Alexander VI. One point of friction which came up in the course of the election was a proposal to contractually limit the number of new cardinals the new pope could appoint. All popes strove to load the College of Cardinals with their kin and allies to ensure that their factions had a leg up in the next election, and over the course of the five popes Rodrigo had lived under the portion of stooges and nephews in the college had ballooned like the bubo of a plague victim. Rodrigo Borgia agreed to a high but reasonable limit (I believe the limit was six, although I could be a little off). Then, still within the blushing springtime of his papacy, he trashed that limit and appointed twelve! One of those twelve Cardinal’s hats went to the Archbishop of Valencia, one of his own bastard sons, Cesare Borgia. It was a strange and strained life growing up a Borgia bastard, with a Spanish father but an Italian mother, raised in Rome. The kids learned Catalan as well as Italian and French, not to mention Latin and Greek, since by 1480 humanism was sufficiently victorious that even a twelve-year-old bastard daughter of nobility received a healthy dose of Homer. The Italians considered the Borgias Spanish, but in Spanish eyes they seemed Italian, making them literally at home nowhere. Even within the walls of their own house, as bastard children of a Cardinal they could not be properly acknowledged, at least not in the earlier parts of Rodrigo’s career. This left them wealthy and well-set-up, but also rootless in a world of enemies. Our protagonists here will be Rodrigo’s children by the primary mistress of his Roman pre-papal years, Vannozza dei Cattanei. He had other bastards both before and after, but none that will interest us as much as Giovanni Borgia (1476/7?-1497), Cesare Borgia (1475/6?-1507), Lucrezia Borgia (1480-1519) and Gioffredo Borgia(1482-1518).

A Pope Like No Other:

Rodrigo now had one goal: permanently establish the Borgia as one of the great families of Europe. He was an old man, and had to move fast. He bought a ducal title for his intended heir, Pier Luigi. When Pier Luigi died, he bought one for the next son, Giovanni, and made Giovanni commander of the papal armies. He married his younger son (Gioffredo, aged 12) to a princess of Naples (aged 16). He filled the College of Cardinals with stooges who owed their positions and fortunes to the Borgia family, and ensured they had no other allies and many enemies, so they had nowhere to turn if they broke from the Borgia fold. And he positioned his “nephew” Cesare in the College as a cardinal, just as his uncle had positioned him.

All this is expected of a Renaissance pope. He spent lavish sums on redecorating the papal apartments within the Vatican palace, with the Borgia bull all over them. He took a new mistress, the young and enchanting Giulia Farnese, and soon the papal palace rang with the cries of a newborn papal princess. He gave vast sums from the Church’s coffers directly to his children, to spend on amassing land and personal troops. He made corrupt appointments of clerics that fed vast sums into the pockets of allies who never went near the abbeys or peoples whose spiritual well-being they were supposed to oversee. He used papal military forces to pursue personal family vendettas, particularly against the Orsini and Delle Rovere. All this was also pretty standard for a Renaissance pope. Here is where it gets exceptional. Cardinals and other powerful figures who opposed the Borgias kept dying–sometimes of symptoms suggesting poison, sometimes of bloody assassinations, sometimes of obviously trumped up court sentences, or of unexplained issues while they were incarcerated in the private papal prison in Castel san Angelo. The estates of the condemned kept getting confiscated by the holy see, and winding up, not in the papal treasury, but privately in the hands of the popes sons and cousins. Giovanni was a Duke, and begins demanding to be treated as the equal of the many Italian nobles who had looked down their noses all those years at the half-Spanish mutts. Cesare, meanwhile, positioned in the papal conclave and with fourteen-or-so other Cardinals appointed by his father and sure to vote his way, was in a good position to succeed his father in the next election. Now the papacy was ready to become a permanent hereditary Borgia monarchy.

In 1494 big problems began, somewhat hard to summarize, but largely revolving around the primary rival Borgia had defeated in that hard-fought 1492 election: Giuliano della Rovere.

- Giuliano della Rovere: “Hey, King of France! This Borgia pope is evil!”

- France: “What’s wrong with him?”

- Giuliano della Rovere: “He’s better at bribing people than I am, and bought the election I was trying to buy! I hate him! I hate him!! I hate him!!!”

- France: “Is that so? What a strange and marvelous age we live in.”

- Giuliano della Rovere: “He’s also Spanish.”

- France: “What? We hate those guys!”

- Giuliano della Rovere: “Please invade Italy!”

- France: “Srsly?”

- Giuliano della Rovere: “To oust the evil Borgia pope and free Rome from corruption that isn’t mine! And if you make me pope, I’ll be your buddy and do whatever you want.”

- France: “Tempting… say, Naples is in Italy, right? I seem to remember my distant cousin being King of Naples…”

- Ludovico Sforza: “Your Highness should totally invade Italy. On the way in, might I recommend attacking Milan?”

- France: “Sforza? Aren’t you the Duke of Milan?”

- Ludovico Sforza: “No, my nephew is Duke of Milan. Please invade Italy, attack my home city, and murder my closest relative!”

- Della Rovere: “Makes sense to me.”

- France: “You Italians have very strange priorities. OK. I suddenly care deeply about this evil Spanish pope. I will oust him!”

- Sforza & della Rovere: “Hooray! France is invading Italy!”

- Italy: “Waaaaaaaaaaaaaah!”

- France: “CRUSH THINGS!”

- Della Rovere: “Hey, don’t crush too much! I want to tyrannize this stuff later.”

- France: “CRUSH MILAN!”

- Sforza: “Thank you!”

- Other Sforza: “You jerk!!”

- France: “CRUSH FLORENCE!”

- Savonarola: “Have you considered not crushing Florence?”

- France: “Oh, I thought you Italians liked being crushed; my mistake.” *gentle condescending head pat*

- Machiavelli: “What the… that worked?! How did that work?!?!”

- France: “CRUSH ROME!”

- Della Rovere: “Excellent! Now, get that evil Borgia pope!”

- France: “Right. Where is this evil Borgia pope?”

- Alexander VI: “Hello, Your Majesty. Would you like me to make you King of Naples?”

- Ludovico Sforza: “Great idea! Go crush Naples!”

- France: “Did you two read my character sheet or something? Yes! Naples! That is indeed what I want.”

- Alexander VI: “I hereby crown you King of Naples. Now you can crush and tyrannize the entire southern half of Italy without consequence. I shall tyrannize the middle, and you and Sforza can share the top.”

- Ludovico Sforza: “Here’s a big bat. Have fun!”

- France: “I AM THE KING OF NAPLES! CRUSH THINGS!!!!”

- Della Rovere: “But, the evil Borgia pope…”

- France: BANG! CRASH!! SMASH!!! “Sorry, can’t hear you, della Rovere, busy conquering Naples.”

- Della Rovere: “Borgia bad! You said you’d oust Borgia!”

- France: “Yeah, I can see why Borgia out-bribed you at the election. He’s way better at this evil pope stuff!” SMASH!!!!

- Alexander VI: “In the name of Saint Peter, CRUSH THINGS!!!!”

- Italy: “Wait, did the papal runner-up just invite the French to invade, and then the pope encouraged them to invade more, and then the pope started a new war of his own to seize the ravaged territories? That’s a new one for the ‘worst popes’ book!”

- Alexander VI: “Della Rovere did it.”

- Della Rovere: “Borgia did it.”

- Savonarola: “THIS POPE IS THE ANTICHRIST! THESE ARE THE END TIMES! APOCALYPSE! JUDGMENT!”

- Everyone: “You know, that explains a lot…”

But he remained the pope, however destructive his exploits. He had armies, money, his own prison-fortress, his own courts of law, political instincts honed by decades, detailed knowledge of everyone’s secrets, the authority to grant noble titles (like King of Naples), and the power to damn you to Hell forever and ever. His every move made him more powerful at the cost of his enemies, so the worse things got, the bleaker the prospect of taking down the Borgia monster.

If you can’t take down the monster, one traditional option is to marry it. Yet in this case, even allying with the pope by marriage, effectively agreeing to permanently condone and support whatever antics he got up to, was not necessarily a permanent fix. The infamous and enchanting Lucrezia Borgia deserves an entry of her own someday, but I will treat her briefly here. She was supposed to be one of the most beautiful ladies in the world, with blonde hair which fell past her knees, and a keen and well-trained intellect. I can testify personally to the latter, since I have read some of the letters she wrote to her father from Milan at the age of fourteen, and the depth of her understanding of the European situation as she warns her father of political turmoil along Italy’s northern border certainly adds plausibility to the impossible competence of a lot of teen-aged young adult and anime protagonists. In marriage terms, she was the best catch in the world. Unfortunately, she was too valuable. Alexander engaged her to one noble, then broke it off in favor of a better one, then a better one (“What’re ya gonna do about it? Her dad’s the pope!”). Eventually he married her to a bastard of the Sforza, the ruling family of Milan, then when the Sforza weren’t valuable enough wrangled an annulment (the Sforza objected fiercely: “You can’t do that! We’re Catholic! Ending a marriage requires a special dispensation from the pop… oh, right. #%$&!”) Next Alfonso of Aragon, from the Naples-Spanish royal family. That one ended in a juicy (and unsolved) murder. All the rumors of corruption that follow corrupt rulers naturally followed the Borgias, and I mean all of them. Every important person who died was poisoned by the Borgias. Every body found floating in the Tiber was their fault. Lucrezia was sleeping with her brothers. Lucrezia was sleeping with her father. Giovanni was sleeping with Gioffredo’s wife. Giovanni murdered his own wife. Cesare murdered Lucrezia’s second husband out of jealousy because he was in love with her. Alexander was sleeping, not just with Julia Farnese, but with Julia Farnese’s brother Alessandro. Alexander was sleeping with the Ottoman Sultan’s brother Cem. Most of these rumors must be untrue, and experts have spent many years making baby steps toward sorting true from false, but the majority is pretty much impossible to verify. It does seem to be true that there was a patch in there when so many Cardinals were being murdered that there were active betting pools in Rome where you could lay money on which Cardinal would be offed next. I myself am half convinced by the numerous accounts that claim that Cesare used to go out in the streets at night and murder people for fun. I mean, why not? His dad’s the pope! Many of the claims may be outlandish, but neither historical facts nor the rule of plausibility can really help us quash them when the facts we do have are so exactly what we would expect if everything was true. For example, in 1498, two of Lucrezia’s household servants were found dead in the Tiber without explanation, and shortly thereafter she definitely gave birth to a bastard, which was officially declared to be Cesare’s son, then to be Alexander’s son, then to be her half-brother with no claim about who the father was. What was history supposed to think? And all this time, the Ottoman Sultan’s brother Cem, who was living in Rome as a political hostage, did spend a suspiciously large amount of time hangin’ with the Borgias.

But these were small things. In 1497, one of the bodies floating in the Tiber was their own. Giovanni Borgia, Duke of Gandia, Alexander’s heir. An untouched purse containing gold worth more than a year’s income to many Romans proved it was not a random murder. Alexander launched an intense investigation, then suddenly halted it after less than two weeks without any announcement of the result. No one was convicted. Rumors blamed the Orsini. Darker rumors blamed his fellow Borgias. Young Gioffredo Borgia was accused, on the grounds that Giovanni was supposed to have been sleeping with his wife. Cesare Borgia was accused on the grounds of… of… frankly, it just seems that everyone who knew Cesare and knew Giovanni and knew the situation just agreed, as if by instinct, that it was Cesare. Nothing else made sense. Fratricide–the narrative demands it.

The Dark Prince Rises:

Why kill Giovanni? [Disclaimer: there is no proof Cesare did kill Giovanni. I freely confess that my tendency to believe those who claim he did is based solely on (A) its consistency with his later actions, and (B) the fact that it feels narratively right. There is no proof!] Cesare was supposed to succeed his father as pope. But Giovanni, he was the one who got to be a Duke, to marry a princess, to enjoy the lands and castles, and to carry on the Borgia name. He had been the heir. The logical next heir should have been Gioffredo. Instead Cesare took center stage. He renounced the Cardinalship, becoming the only man in history ever to do so. His father pressured the French into giving him a princess for a wife, and a Ducal title. So little did the actual people ruled by nobles matter to the aristocrats who owned them at the time that they decided to make him Duke of a region called Valentinois for the sole reason that, as Archbishop of Valencia, he was already nicknamed “Valentino”, and this way they wouldn’t have to change his nickname. He took command of the papal armies, and control of the Borgia estates. But Alexander continued to sort-of treat him as a Cardinal and he continued to sort-of act like one, making everyone worry that they might still intend Cesare to succeed his father as pope even though he was now also intending to succeed as worldly heir. What did it mean?

Titular power was not enough now. During Giovanni’s years, Alexander had already started signing papal lands over to his son-and-heir, not as temporary leases but as permanent gifts, carving off pieces of the Papal States and creating a private Borgia kingdom out of what had been Rome’s. You see, titular ducal titles like Gandia and Valentinoi,s to Italian eyes, just meant some faraway nowhereville which gives people money and makes us have to call them “Your Grace”. Such territories didn’t matter, not like a territory in Italy would matter. What Alexander and Cesare made now was different. Alexander gave a big hunk of the papal states to Cesare, as a permanent gift. The cities within the Papal States were governed by papal “Vicars,” i.e. nobility granted rule over sub-territories within the papal lands much as Dukes and Counts are granted sub-territories in a kingdom by a king or emperor. These vicars were in theory appointed by the pope and could be replaced by him, though in practice the position was by custom passed along noble lines from father to son. To depose them all and give their lands to his son as the new vicar was thus technically legal but practically unthinkable, and an as great a shock to the political scene as if a king of France had suddenly deposed half his top nobles. It also implied Alexander’s intention to leave these territories in Borgia hands permanently. Next Cesare raised armies and started, on small pretexts, attacking neighboring city-states and territories, ejecting the current rulers and adding them to his private Borgia kingdom. (“What’re ya gonna do about it? My dad’s the pope!”) A new blotch appeared on the European map. Let me repeat: a new blotch appeared on the European map, a kingdom out of nowhere, carved out in the heart of Italy, a kingdom which no longer belonged to the pope, or any Italian house, but to the Borgias. Whether Cesare became pope next or not, he would be Duke—perhaps soon King—of an ever-growing chunk of the world. No pope had done this. No pope had done anything close to this.

The new and growing Borgia Kingdom was an especially terrifying force in the eyes of those on its ever-changing borders. The pattern rapidly became clear: ally with the pope–by marriage or treaty–or you are next on Cesare’s chopping block. These were not subtle takeovers but outright sieges, with the full brutality of Renaissance warfare. Even Ferrara—the untouchable no man’s land between Venice and Rome which no man dared disturb lest strife on the Venetian border weaken the power whose fleet was the only barrier between the Turk and Christendom—even here Cesare threatened war. The threat of war with the Turk meant nothing to him. He was ready to ravage Ferrara, and would have if the Duke hadn’t speedily married Lucrezia and agreed to condone and acknowledge all his new brother-in-law’s conquests. So even the untouchable noble house of Este fell into Borgia hands. And do you know what plump, gold-fatted city-state lay directly west of the patch where Cesare was playing king-unmaker? Good guess.

Good morning, Mr. Machiavelli. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to prevent Cesare Borgia from conquering Florence. You will serve as our official ambassador to his court. You will shadow the Duke-Cardinal as closely as possible, report to us about his character and tactics, and develop a strategy to keep him from adding Tuscany to his expanding kingdom. While at his court, you will need to maintain yourself and your team with grandeur sufficient to make him take us seriously as a political force, but we can’t send you any funds to pay for this, since Borgia has so completely destroyed peace and order in the region that bandits are rampaging through the countryside robbing and murdering all our couriers. As always, should you or any member of your team be caught or killed, the Signoria will disavow all knowledge of your actions. This message will self-destruct in a few weeks when your office is inevitably looted and burned, but if you throw it in the fire that will speed things up.

Thus began Machiavelli’s very special education in the conduct of a different kind of prince.

Cesare Borgia was both feared and loved. The “loved” part may seem out of place given Borgia infamy, but it was true. The papal vicars Cesare replaced had been widely disliked by the peoples they ruled, since most of them were corrupt and more interested in family advancement than their people’s well-being. Cesare offered something different, and in many cases better. Better how? Because the fundamental purpose of government, from the perspective of a butcher or a weaver, is to keep the peace and prevent killing and looting. Cesare did that. Cesare did that very, very well. How? If someone was caught causing strife in the streets, that person would be executed in the most horrifically graphic possible way and his corpse strung up in public. Consequence: peace. Two examples of Cesare’s activities in this period crop up particularly vividly in the history books, and in Machiavelli’s “little book on princes.” The first is the case of Remirro de Orco. Cesare conquered the territory of Romagna (East/middle hunk of Italy), including the city of Cesena. Such was the chaos resulting from the violent upheaval and expulsion of the old rulers, that the region of Romagna had largely degenerated into chaos, banditry, killing and looting. Cesare needed to bring order. He appointed a mercenary captain named Remirro de Orco, one of his more loyal men, and commanded that he bring peace to the area as efficiently as possible by using maximum brutality. Following Cesare’s order, Remirro carried out numerous executions, using methods gruesome even for the Renaissance, and speedily crushed the region under the iron heel of peace. No one looted. No one dared. After peace was achieved, Cesare inspected the region and confirmed that it was indeed stable, arguably even more prosperous than it had been before his conquests, but that the people were fired with bitterness and rage. The next morning, Cesare had departed, and Remirro de Orco was found in the town square of Cesena, having been sliced in half, with his gore-spewing entrails strewn across the decorative pavement. No one doubted it was Cesare’s doing, but to Machaivelli’s astonishment, the effect of this unthinkable betrayal was instant and lasting peace. The people were satisfied, even grateful, that Cesare had taken revenge upon the brutal oppressor, and the new, gentler vassal he left in place to rule the region was readily obeyed. They did not blame Cesare for the atrocities loyal Remirro had carried out at his express order – instead they thanked him for avenging them. Cesare was loved.

He was also feared, by other loyal vassals who noticed (as my father urged Crabbe and Goyle to) that the villain had a tendency to brutally murder people near him, even loyal servants. This was unheard of. The Handbook of Princes says the success of the prince depends on his ability to inspire loyalty and love from his vassals. The vassal betraying the benefactor is the worst thing in Dante’s Inferno; Dante didn’t even have a section for benefactors who betray their vassals because it simply didn’t occur to the Renaissance political mind that one would ever want to. But it did occur to Cesare. By this phase, by the way, Cesare’s face had been disfigured by syphilis, and he had taken to wearing a mask. And dressing all in black. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, he genuinely did go around dressed all in black wearing a mask, betraying and murdering people. Sadly, we have no documentary evidence that he went “Wa ha ha! Wa ha ha ha ha!” The nervousness that swept through Cesare’s vassals leads us to the second amazing incident, the massacre at Senigallia. In very late 1502, several of the vassals who had supported Cesare in return for receiving power under him and having his help crushing their enemies became increasingly afraid, both for their lives and for Italy and Europe, and plotted against him. This was really quite rational. But they were disorganized and uncertain, and did not follow through well. They heard rumors that Cesare had heard about the plot. They didn’t quite trust each other not to sell each other out to him. One problem led to another, and in the end they decided to abandon the plot, confess to him that they had considered treason but renew their vows to follow him to the end, and beg his forgiveness. They confessed. He forgave. They rejoiced. He invited them to join him for a feast. They heartily accepted. He massacred them all. High on Olympus Hestia sighed, and the vengeful Furies in the depths gnashed their teeth as the Laws of Hospitality lay wounded. Cesare’s vassals never plotted against him again.

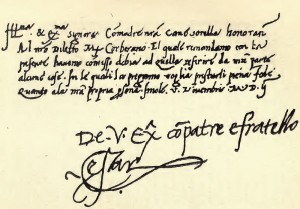

I will never forget the letter written to Machiavelli by his friend Biagio Buonaccorsi on January 9th 1503, expressing absolute delight and abject gratitude and relief upon hearing that Machiavelli had survived the massacre at which so many of Cesare’s court had been killed. Throughout this period, dear Niccolo’s friends and family were prepared to read any day that he had been killed, either with Cesare or by Cesare. And they didn’t manage to send him his salary. Once they tried giving it to Michelangelo to carry to him when he was en route to Rome, but even Michelangelo turned back in Cesare-ful times of banditry and chaos. But something else unsettling was happening too. What of our Handbooks of Princes? Shouldn’t a betrayal like that make the rest of Cesare’s vassals turn and flee? Shouldn’t these people rebel hearing rumors of his brutality? Doesn’t the Handbook of Princes genre teach us that every move Cesare is making should fail? Then why does every step he takes seem to be a step up? They’re trying to turn the papacy into a hereditary monarchy, and they’re succeeding. It should be noted that Cesare’s rise does not necessarily completely undermine the advice in the traditional Handbook of Princes. Providence has exalted tyrants before, and fools have followed them, many out of of fear. The apparent (psychological) effects of the incidents with Remirro and at Senigallia are hard to explain, but this can still fit traditional narratives, especially if the Borgias fall in some appropriately cataclysmic way, demonstrating the wages of sin and the grisly fate that waits for bad princes and bad popes. Then Cesare’s story can join our collections of moral anecdotes as an example of hubris and cruelty, while one of his enemies (Guidobaldo da Montefeltro perhaps?) becomes the hero. But for now, hubris and cruelty seem to be winning the day.

Machiavelli’s letters from the period include some of his reflections on these larger philosophical and historical questions, but he does not have the leisure to invent political science just now. That must wait for the leisurely days of his exile. On this mission, every second is reserved for Florence. Seeing all who opposed the rising prince fall one by one, Machiavelli too chose to follow fear’s advice and suggested an alliance. Florence accepted his plan and, after many careful approaches by their wily ambassador, so did Cesare. Florence became an official Borgia ally, agreeing to recognize Cesare’s legitimate claim to his newly-carved kingdom and to offer money and resources to help him conquer more. Florence was safe for now—at least, as safe as Remirro de Orco had been. And it is in this precarious state that we must leave Florence, and Machiavelli, and the triumphant Cesare for a little while, as the spring of 1503 promises Great Change.

Continued in Machavelli IV: Julius II, the Warrior Pope

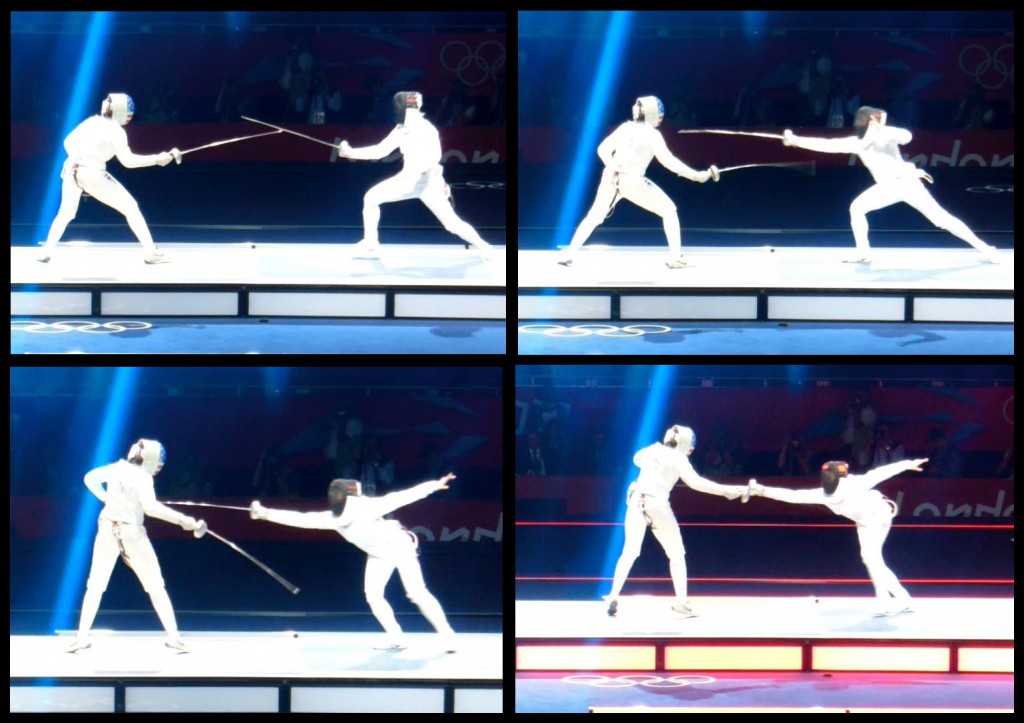

Since our chance to watch it is this weekend, I can’t resist a quick plug for what I consider easily the most exciting Summer Olympic sport, despite being generally regarded as the most obscure: the Modern Pentathlon. I know most mixed events are obscure and, at first glance, somewhat arbitrary, but when you learn the idea behind the Pentathlon, even the most hardcore non-sports-fan has to get somewhat excited.

Since our chance to watch it is this weekend, I can’t resist a quick plug for what I consider easily the most exciting Summer Olympic sport, despite being generally regarded as the most obscure: the Modern Pentathlon. I know most mixed events are obscure and, at first glance, somewhat arbitrary, but when you learn the idea behind the Pentathlon, even the most hardcore non-sports-fan has to get somewhat excited.

The competition is a test of the skills required when escaping from behind enemy lines after being captured. The competitors must fence (staving off the guards), shoot with a pistol (stolen from the enemy), swim (crossing a river), ride jumping over barriers on an unfamiliar horse (again stolen from the enemy), and run to a finish line (representing the safe border of friendly territory). The riding event on a horse the competitor has never met before is a particularly tricky variant on show jumping. The swim, fencing and riding are held earlier in the day, and successes or failures there are translated into points which turn translate to head starts or handicaps in the foot race, at which the first to the finish line is victor. In recent versions, the shooting has been done during the run itself, so the athlete (i.e. escapee) must stop mid-run at maximum exertion and then shoot a target (i.e. enemy assailant). The faster a competitor can land the required shots accurately on the target, the sooner he or she can return to the all-important run. Like in the biathlon (whose combo of skiing and shooting represents northern European military exercises), it takes a special kind of physical mastery to keep the racing heart, shaking and quick breathing from the run from unsteadying the hand.

The competition is a test of the skills required when escaping from behind enemy lines after being captured. The competitors must fence (staving off the guards), shoot with a pistol (stolen from the enemy), swim (crossing a river), ride jumping over barriers on an unfamiliar horse (again stolen from the enemy), and run to a finish line (representing the safe border of friendly territory). The riding event on a horse the competitor has never met before is a particularly tricky variant on show jumping. The swim, fencing and riding are held earlier in the day, and successes or failures there are translated into points which turn translate to head starts or handicaps in the foot race, at which the first to the finish line is victor. In recent versions, the shooting has been done during the run itself, so the athlete (i.e. escapee) must stop mid-run at maximum exertion and then shoot a target (i.e. enemy assailant). The faster a competitor can land the required shots accurately on the target, the sooner he or she can return to the all-important run. Like in the biathlon (whose combo of skiing and shooting represents northern European military exercises), it takes a special kind of physical mastery to keep the racing heart, shaking and quick breathing from the run from unsteadying the hand.