Spot the Saint: Mary Magdalene and John the Evangelist

It’s been a while, so here are some extra trixy new saints to add to our challenge. (Note, the Renaissance images featured in this post will feature nudity, so if you’re not comfortable with that skip this entry):

John the Evangelist (Giovanni Evangelista)

John the Evangelist (Giovanni Evangelista)

- Common attributes: Eagle, book, pen, Roman robes, EITHER beautiful young man OR old man with very long beard

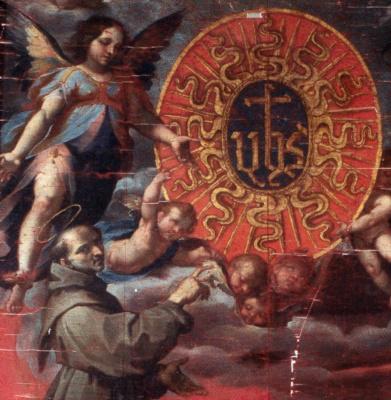

- Occasional attributes: Chalice with a snake or dragon crawling out of it, often dressed in pink

- Patron saint of: Friendship, everyone in the bookmaking industry (writers, editors, compositors, booksellers, bookbinders, print makers, engravers), protection from burns, protection from poison

- Patron of places: Asia Minor, Umbria, Wroclaw Poland, Sundern Germany, lots of weird places like Cleveland and Milwaukee and Boise Idaho

- Feast day: December 27th, also May 6th (his surviving being boiled in oil).

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, mourning at the Crucifixion or Deposition, asleep in Christ’s lap at the Last Supper, being boiled, in a set with the other three Evangelists

- Relics: Ephesus (church has now been turned into a Mosque)

Due to the popularity of Crucefixion scenes, the most commonly depicted apostle in Renaissance art is not, shockingly, Peter, nor Paul, but John the Evangelist, who, like the fainting Virgin and tearful Magdalene, makes a mandatory cameo at the base of every cross. Add to this the frequency with which artists decorate four matching surfaces (four vaults, four doors, four pinacles above central images) with the Four Evangelists, and the frequency with which John is depicted writing his Gospel or witnessing events of his Gospel, and he becomes one of the most familiar faces in our list.

Familiar but tricky. John the Evangelist, or “the Beloved”, presumed author of the Gospel of John, is a great challenge to saint spotting for three reasons. First: he often has no attributes, and has to be identified from his general bearing, location and activities. Second: he appears at two completely different ages, which can throw one off. Third: when young he often looks so female to the modern eye that the mind leaps straight to our list of female saints, looking for spiked wheels and eyes on plates, without considering the fact that this might be a boy. The fact that he appears so often in the same scenes where Mary Magdalene makes sense to appear makes the two of them frustratingly easy to mix up.

Familiar but tricky. John the Evangelist, or “the Beloved”, presumed author of the Gospel of John, is a great challenge to saint spotting for three reasons. First: he often has no attributes, and has to be identified from his general bearing, location and activities. Second: he appears at two completely different ages, which can throw one off. Third: when young he often looks so female to the modern eye that the mind leaps straight to our list of female saints, looking for spiked wheels and eyes on plates, without considering the fact that this might be a boy. The fact that he appears so often in the same scenes where Mary Magdalene makes sense to appear makes the two of them frustratingly easy to mix up.

John’s radically fluctuating age is due to the fact that he is believed to have lived a very long time, and did important things at many different points in his life, unlike martyrs who are pretty-much always shown at the ages they were when they died. He was established as having been very young (and handsome) during Christ’s life, and can be spotted among full sets of apostles by being the most handsome, and often the only one without a beard. He then went on to live a very long life preaching and writing, and survived numerous near-martyrdoms: He was arrested and beaten by Domitian, but remained impervious. He was then poisoned, but he blessed the chalice and the poison turned into a snake or dragon and ran away (Where did it go?! Is it still out there?…), hence his attribute of holding a cup with a snake in it. He was then boiled in oil, but that didn’t work either, and he escaped to Ephesus where he lived a long and pious life. He also supposedly got into a conflict with some worshipers of Artemis at one point, who tried to stone him, but the stones bounced off, and then at his invocation two hundred of them were killed by lightning, and then resurrected, in one of the largest mass-resurrections in the palette of saintly miracles. But because none of the implements involved in these stories actually killed John, he does not carry them around with him in Heaven (i.e. in art), so while Lorenzo and Catherine and Paul have convenient death tags, John remains elusively short on attributes.

John is depicted either as a beautiful youth, or as an old man with a very long beard. Modern gender tag conventions make his youthful form particularly easy to mistake for a woman, mainly because of his hairstyle, which is usually long and loose down to his shoulders or shoulder blades. This style looks feminine by modern standards, but was not by Renaissance standards. In Renaissance art, pretty-much no woman would ever have hair nearly that short. Women’s hair is generally to the elbows, and is worn tied up in an elaborate hairstyle, or at least covered by a veil. Loose hair with nothing tying it up is the style of a knight or dashing nobleman, never a woman. The to-modern-eyes feminine presentation of John the Evangelist is enhanced by the fact that, at least in Tuscan art, he’s usually dressed in pink. I don’t know why this is, and it certainly isn’t a solid rule, but just as the Virgin Mary is almost always in a blue robe, John is almost always in pink, which was not gender-coded in the Renaissance as it is now, but does rather add to the overall effeminacy of the young “beloved”.

The Four Evangelists have four winged animals that represent them: the Winged Lion for Mark, the Winged Bull for Luke, the Winged Person i.e. Angel for Matthew, and the Winged Eagle for John (no, no one has a non-winged Eagle as an attribute). Sometimes just the animal is used to stand in for the evangelist, with no human figure at all. The evangelists’ animals are sometimes depicted covered with lots of eyes, but more often John just has an eagle hanging out next to him. This, combined with John’s youth and beauty, strongly invokes the Greco-Roman image of the handsome Ganymede being carried of by Zeus in the form of a lustful eagle, and puts John solidly with Sebastian in the palette of “sexy saints,” i.e. saints who are sometimes used as an excuse to show a sexy male body in a world in which eroticism, particularly homoeroticism, was controversial, yet religious content often eased criticism. We have Renaissance diatribes in which theologians rail against the sensuality of paintings in aristocrats’ collections, citing nude Venuses and scandalous Ganymedes, but the same treatises often explicitly say that nudity is A-ok in religious art, because the bodies of John, Sebastian and Mary Magdalene point the soul toward heavenly thoughts rather than Earthly. Looking at them, though, it is sometimes hard to see the difference:

The Four Evangelists have four winged animals that represent them: the Winged Lion for Mark, the Winged Bull for Luke, the Winged Person i.e. Angel for Matthew, and the Winged Eagle for John (no, no one has a non-winged Eagle as an attribute). Sometimes just the animal is used to stand in for the evangelist, with no human figure at all. The evangelists’ animals are sometimes depicted covered with lots of eyes, but more often John just has an eagle hanging out next to him. This, combined with John’s youth and beauty, strongly invokes the Greco-Roman image of the handsome Ganymede being carried of by Zeus in the form of a lustful eagle, and puts John solidly with Sebastian in the palette of “sexy saints,” i.e. saints who are sometimes used as an excuse to show a sexy male body in a world in which eroticism, particularly homoeroticism, was controversial, yet religious content often eased criticism. We have Renaissance diatribes in which theologians rail against the sensuality of paintings in aristocrats’ collections, citing nude Venuses and scandalous Ganymedes, but the same treatises often explicitly say that nudity is A-ok in religious art, because the bodies of John, Sebastian and Mary Magdalene point the soul toward heavenly thoughts rather than Earthly. Looking at them, though, it is sometimes hard to see the difference:

The old John, author of the gospels, is often depicted with the other three evangelists in a set, but sometimes he is depicted as just a bearded sage with a book and an eagle, or, less helpfully, with just a book, or even less helpfully as just a bearded man, though, often, still in pink robes. Sometimes, to mix things up, he’s just an eagle.

The old John, author of the gospels, is often depicted with the other three evangelists in a set, but sometimes he is depicted as just a bearded sage with a book and an eagle, or, less helpfully, with just a book, or even less helpfully as just a bearded man, though, often, still in pink robes. Sometimes, to mix things up, he’s just an eagle.

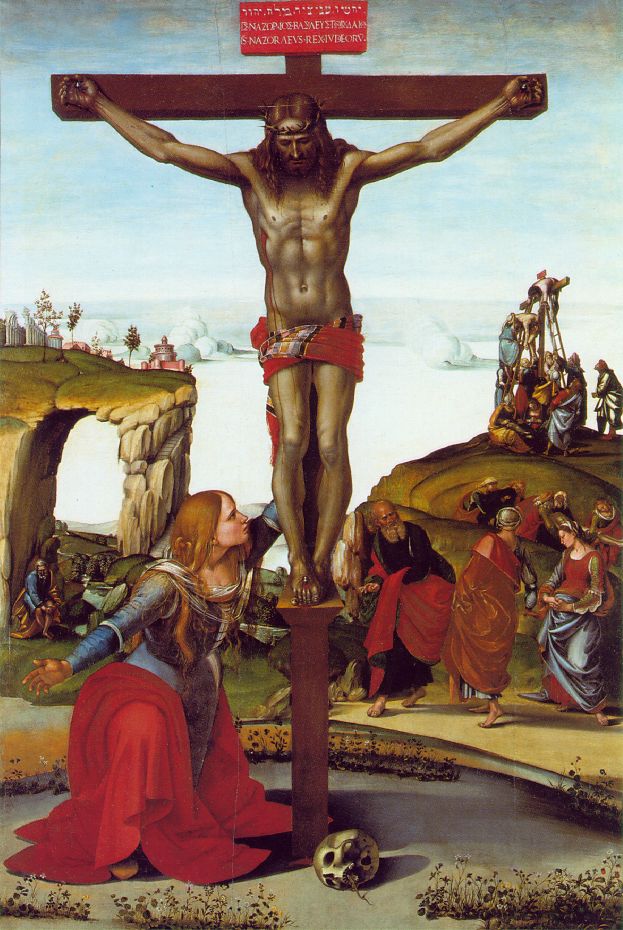

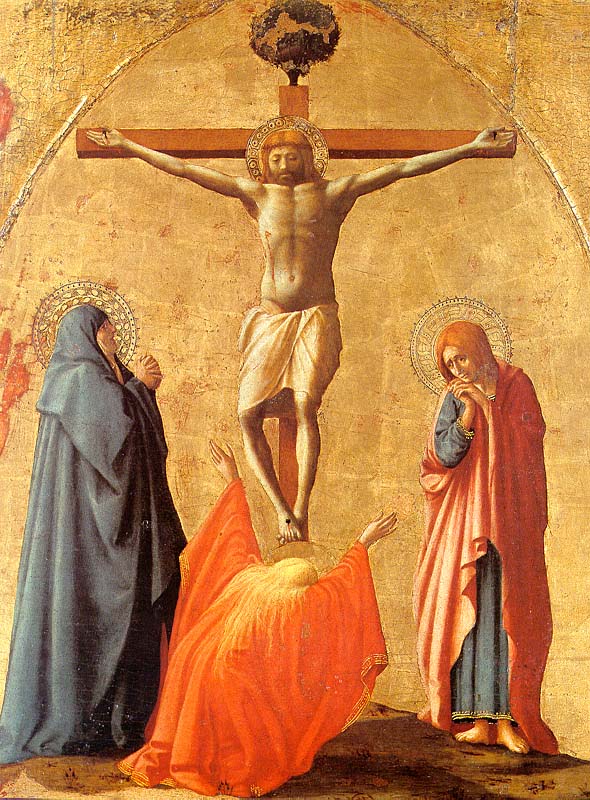

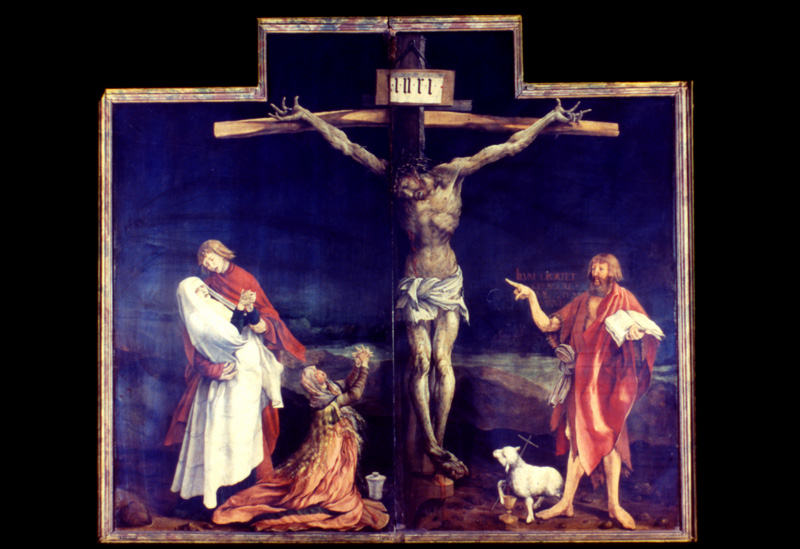

One way to spot John when he has no attributes is by his customary position. At a Crucifixion, John is always depicted near the foot of the cross, mourning dramatically, accompanied by Mary Magdalene, the Virgin Mary and ladies attending to the Virgin, usually including Margaret. Thus, if there are several beautiful mourners at Christ’s feet, the one with the shortest hair is John. The gender tags remain trixy, however, and unless one knows what to look for in the hair styles, it can be difficult to tell the difference between John and Christ’s other major mourner, Mary Magdalene.

Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene

- Common attributes: Long loose hair

- Occasional attributes: Ointment jar (often made of alabaster) or cup, skull, naked except for her hair

- Patron saint of: Penitent sinners, converts, the contemplative life, apothecaries, women, reformed prostitutes, protection against sexual temptation

- Patron of places: Atrani, Italy

- Feast day: July 22nd

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, grieving at the Crucefixion or Deposition, anointing or embracing Christ’s feet, in the wilderness being a hermit, being airlifted to heaven by angels, with Christ in the garden attempting to touch him while he refuses (“noli me tangere”)

- Relics: Either Constantinople OR the French hemitage on La Sainte-Baume, depending who you ask

Ah, Mary Magdalene, unofficial patron saint of conspiracy theorists, historical mystery fiction and feminist historicist conflicts. There is either way too much information about Mary Magdalene or way too little, depending on what sources you listen to. Our goal is to present the version which appears in Renaissance Art, as opposed to the skillion other versions, from Mary “Equal of the Apostles”, to Mary the systematically-suppressed founder of a long-lost feminist Christianity, to… I don’t actually know what she is in the Korean comic “Let’s Bible!” but given that Jesus is a teenage girl with no pants and Satan is a Mexican guitarist, I think I am safe in assuming that she is a talking spider plant.

In the Gospels, apart from a vague reference to her being cleansed of “seven devils”, and being Lazarus’ sister (even this is debated), she pretty-much only appears during the Crucifixion process, at which she is a named and specified witness of (A) the Crucifixion, (B) the fact that the tomb is empty, and (C) the Resurrection. Renaissance artists depict her consistently at all these things, accompanied at the Crucefixion and tomb by the Virgin Mary, the confusingly vague “Other Mary”, and at the Crucifixion by them along with John the Evangelist and, often, Margaret.

In the Gospels, apart from a vague reference to her being cleansed of “seven devils”, and being Lazarus’ sister (even this is debated), she pretty-much only appears during the Crucifixion process, at which she is a named and specified witness of (A) the Crucifixion, (B) the fact that the tomb is empty, and (C) the Resurrection. Renaissance artists depict her consistently at all these things, accompanied at the Crucefixion and tomb by the Virgin Mary, the confusingly vague “Other Mary”, and at the Crucifixion by them along with John the Evangelist and, often, Margaret.

Gregory the Great (in 591 AD) is credited with establishing the idea that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute, who renounced and reformed her evil ways when she converted, and it is this version who populates Renaissance art as the second-most-commonly-depicted woman after the Virgin. She is thus usually a very beautiful, sensual young woman, the cultural antithesis of the Virgin, and a figure which lets Renaissance religious art have a conversation about female sexuality in a way that the endless martyred virgins like Catherine and Lucy can’t facilitate. The legend also has Mary Magdalene go out into the wilderness after the Crucifixion and live as a hermit, allowing her to be used as a prototype for serious female participation in the extreme religious life of total commitment, contemplation and self-denial which made hermits and, later, monks such a central part of medieval Christian ideas of true religious life. Remember that, until St. Francis’s revolutionary program of bringing religious life to the urban lay population, the term “religious” in European culture meant a hermit, priest, monk or nun, who were considered the only people with meaningful religious lives, and the only ones likely to go to heaven without being martyred. The archetype of Mary Magdalane, female hermit, opened this to women.

As champion and representative of the Contemplative Life, Mary Magdalene is patroness of contemplative philosophers, and of the Dominican order, which so values contemplation as a path to the divine.

While the Mary Magdalene story could serve to open some doors of religious activity to women, it also closed some in the form of the “Noli me tangere” scene. This scene, frequently depicted in art, was when the resurrected Christ appeared to Mary (before he did to anyone else) and, when she attempted to embrace him, said “Don’t touch me” (Noli me tangere). This scene is sometimes used to justify refusing to allow women to be priests, where they have to consecrate and touch the body of Christ. The scene in which Thomas, after doubting the resurrection and saying he won’t believe until he touches Christ’s wounds, is then actually allowed to touch Christ’s wounds is used to demonstrate that men can touch him but not women. The fact that Mary Magdalene was allowed to anoint Christ’s body when he was dead leads to all sorts of confusing cultural attempts to figure out the correct divisions of male and female physicality in liturgical, medical and funerary situations which I will not attempt to sort out.

The thing which makes Mary Magdalene recognizable 95% of the time in art is the fact that she has long loose trailing hair. This derives from (A) the pre-modern association between loose hare on a woman and wantonness/ sensuality/ prostitution, and (B) a medieval legend that, when Mary renounced being a prostitute and threw away her luxurious seductive clothes, her hair miraculously grew to cover her nakedness. And even though the miracle of her long hair happens at a certain point in the logic of her linear narrative, the same special relationship with time that allows renaissance artists to cheerfully depict toddler-aged John the Baptist in a hairshirt and carrying a staff allows them to depict Mary Magdalene’s miraculously long hair at any point.

Another fun Mary Magdalene legend moment, also medieval, describes the fact that she refuses to eat while in the wilderness, so to keep her alive angels air-lift her to Heaven every day where she is fed divine manna and then set down again.

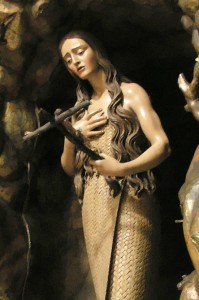

All this makes Mary Magdalene the top choice saint for painters who want an excuse to depict a sexy woman, just as the usually-nearly-naked Saint Sebastian is the top choice for depicting a sexy man. Saint Sebastian can be depicted as a fully clothed guy holding an arrow, but is usually a luscious youth with a gauze-like loincloth, and in the same way Mary Magdalene can be a haggard penitent hermit, or she can be a luscious nude, chest heaving with ecstatic (religious) excitement, indistinguishable from Lady Godiva. Thus we encounter extremes with Mary, as we do with John, ranging, in her case, not in age, but in sensuality, from the extreme of Titian’s Magdalene, whose luscious hare carefully covers everything except the naughty bits, to Donatello’s gaunt and stunning hermit.

The disparity of how Mary Magdalene is depicted is perhaps best summarized by who artists tend to pair her with, since saints are most often spotted in symmetrical groups flanking Christ or the Virgin, and thus every one needs a partner symmetrically opposite. Often “reasonable Magdalene” (as I think of her) beautiful, in nice clothes, with long flowing hair and her jar, is paired with John the Evangelist, the two beautiful, young people who loved and were emotionally close to Christ the man. In contrast, “hermet Magdalene” is usually paired with John the Baptist (her hair paralleling his hairshirt), or to the old wasted hermit Saint Jerome, so the pair of them can kneel on rocks and beat their breasts and contemplate skulls and crucifixes in the wilderness in parallel. Finally “sexy Magdalene” is usually alone, as an excuse to have a naked lady.

But don’t forget to look for the jar – she does have it sometimes.

Population of a Crucefixion Scene:

With John and Mary Magdalene under our belts, it is now possible to sort the population of a standard Crucifixion scene. Generally not all of these figures are present, but the scenes often include:

- Virgin Mary, generally wearing a hood/veil, and depicted fainting into the arms of companions

- Mary Magdalene, with long beautiful hair, generally embracing the foot of the cross, or otherwise grieving very conspicuously, with arms flung wide

- John the Evangelist, also grieving conspicuously, occasionally helping those who catch the fainting Virgin

- St. Margaret and “The Other Mary”, nondescript women catching the Virgin Mary while she faints

- A skull at the base of the cross, supposed to be Adam’s skull, because he was buried at the same place that the cross was set up

- The Good Thief and the Wicked Thief, crucified on two other crosses on the either side of Christ, with the Wicked Thief on Christ’s left having his soul carried of by a (usually adorable) little devil.

- St. Longinus, the centurion who stabbed Christ with a spear, depicted carrying a spear, sometimes on horseback. May or may not have a halo, since at the moment he does the stabbing he hasn’t yet converted, so some artists show him not-quite-yet a saint and therefore halo-free

- Other non-saint figures, including the soldiers playing dice to see who keeps Christ’s clothes, an unappealing man mocking Christ’s thirst by offering him a sponge dipped in vinegar on a long pole (the Holy Sponge!), and assorted random witnesses who are sometimes so plentiful that it starts to feel like they must be time travelers gathering to watch the occasion

- Angels with cups (the holy grail) catching the dripping blood

- Other random saints who logically shouldn’t be there, like John the Baptist, or Francis or Dominic, or whoever is the local patron saint is, stuck in by the artist and shown as witnesses, contemplating the scene and grieving, or, in John the Baptist’s case, pointing at Christ.

The population of a Deposition, when they take the body down and mourn it, is about the same.

Samples:

Quiz Yourself on the Saints You Know So Far:

The next level of challenge in saint spotting is judging when you do and don’t know figures. In the image below, you should recognize five of the seven figures. (One figure is deceptive, since the figure on the left holding lilies is, in fact, a portrait of a more obscure local figure made to look like a more famous one, but you should be able to identify who he’s pretending to be).

Some comments on the old figure second from the right (read these after you have done your best to identify everyone in the picture). It is often possible to figure out a fair amount about a figure even if you don’t know who it is from looking at details of costume. Looking at this figure, you can tell first what religious order he is a part of from his clothes, and from the extra decorated band on his habit you can tell he held a high rank, probably a bishop. Now, note his halo. See how, while everyone else’s halo is a circle, his is instead a bunch of linear rays coming from his head? Artists sometimes use this technique, employing two different halo styles in one painting, to differentiate full saints (with the round halos here) from someone who is beatified, i.e. who has gone through the first three stages of becoming a saint but not the last one. Someone who is beatified has been examined officially by the Church, which has determined that the person is in Heaven and capable of using their position in heaven to intercede with the divine on behalf of people, but who has not yet had the three confirmed miracles necessary to establish sainthood. Historically, beatification was controlled more by local officials, so that bishops had the authority to beatify local people, while sainthood always required Vatican approval. Reverting to our Kingdom of Heaven terms for a moment, someone who is beatified is at court, but hasn’t yet succeeded in securing any notable favors from the king, so is a less certain benefactor than an established court favorite like John the Baptist or St. Francis. For example, Pope John Paul II is currently beatified, but not yet officially a saint. Long-term, cult followings for figures who are beatified but never canonized are sometimes actively discouraged by the Vatican, which usually has a reason for denying sainthood to such a figure if they do. For example, Charlemagne was beatified but never canonized, and when the power struggles between Pope and Emperor as rival claimants to imperial power got tougher, the Vatican actively suppressed the cult of Beato Carlo Magno in order to monopolize heavenly authority – this, however, is why Charlemagne is sometimes depicted with a halo, and his remains are stored in fancy reliquaries and treated as holy relics.

Thus, whoever this figure in the painting is, you can tell by looking, has been beatified but not yet canonized at the point that the painting was done. Since beatified figures are usually only popular in the areas where they lived, when you see a beatified figure like this, it’s a safe guess that the painting was done in the figure’s home town, or somewhere (s)he was active, and that it may well have hung over the beatified figure’s tomb, or in a church where (s)he worked.

The presence of two different distinct styles of halo is thus a marker that can help you nail down a painting’s origin. Note: some artists use linear halos for everyone, so you can’t always say a linear halo = a beatified figure, rather what you need to look for is two different types of halo in one painting. At other times artists use the same technique to differentiate other weird kinds of things, for example an altarpiece I saw at the Accademia last week which had round halos on a bunch of female saints and linear halos on some allegorical ladies who were hanging out with them. This can also be used to differentiate saints from angels, and from Virtues, like Temperence and Strength/Fortitude, who also hang out in Heaven when they’re not busy crushing Vices underfoot or participating in Tarot readings.

Small, cheaply-decorated plastic mask (including Bauta) €12-25

Small, cheaply-decorated plastic mask (including Bauta) €12-25