So Much Shakespeare!

I am posting mainly to announce that I have a new essay up on Tor.com, “How Pacing Turns History into Story: Shakespeare’s Henriad and the White Queen TV.” I’ve been doing preliminary work for this new post for 2 years now (by preliminary work I mean watching masses of Shakespeare over and over), and it follows up on my earlier posts about historical TV series, “How History can be Used in Fiction: The Borgias vs. Borgia: Faith & Fear” and “The Hollow Crown: Shakespeare’s Histories in the Age of Netflix.”

I am posting mainly to announce that I have a new essay up on Tor.com, “How Pacing Turns History into Story: Shakespeare’s Henriad and the White Queen TV.” I’ve been doing preliminary work for this new post for 2 years now (by preliminary work I mean watching masses of Shakespeare over and over), and it follows up on my earlier posts about historical TV series, “How History can be Used in Fiction: The Borgias vs. Borgia: Faith & Fear” and “The Hollow Crown: Shakespeare’s Histories in the Age of Netflix.”

Separately, in case anyone missed it, I also had a shorter piece up on Tor.com on December 1st, an obituary honoring Japan’s Folklore Chronicler Shigeru Mizuki (1922-2015), a great folktale collector, war historian and manga author. Even if you aren’t interested in manga/anime, I recommend glancing at it to learn about his powerful contributions to anthropology, folklore preservation, and post-WWII peace efforts. Meanwhile…

Too Much Shakespeare?

Too Much Shakespeare?

It’s been an odd experience, but I have been watching pretty-much no media that isn’t Shakespeare for 2 years. I’ve made exceptions for the kinds of ubiquitous media (i.e. Star Wars) which are bare minimums for keeping current in nerd culture, but between my transition to Chicago and looming novel revisions there hasn’t been time for anything else. It’s fascinating observing what that’s done to my brain, shifting my entertainment expectations. I’ve joked a couple times that, “Now when I try other TV it just isn’t as good as Shakespeare,” but it’s more complex than that, and there are certainly sections of Shakespeare–a bad, un-funny production of Love’s Labour’s Lost, or the second half of Timon of Athens–which do not shine in contrast with today’s best TV. I discuss most of my observations in my Tor essay, but my main observations are these:

First, people don’t say very much in current TV, at least in drama. Lots of screen time is devoted to vistas, establishing shots, standing there looking cool, and to gazing dramatically at one another. A giant, long-awaited confrontation or confession scene will still often only involve ten or fifteen lines of dialog at most, leaving my Shakespeare-saturated brain demanding, “Tell him more! Tell her more! Tell me more! Ask questions! Explain your reasoning! Say what you really think!” It’s amazing to me how many conflicts in the few TV dramas I have watched recently are caused by Character A facing Character B and announcing “I want X” and Character B responding, “I oppose X so now we’re enemies,” and the viewer knows the real reasons both characters want these things and that if Character A would just tell Character B her/his thought process they would reach a compromise, but they don’t because they don’t explain, and don’t ask. I think such scenes are aiming at sympathetic tragedy, the viewer realizing that all the strife to come is the result of a misunderstanding, and making it easy for the viewer to sympathize with both sides. Over and over, five minutes’ more conversation would mean no one has to die. With the exception of Othello, Hamlet and some moments in the comedies, Shakespeare’s characters generally explain their why in addition to their what, but Shakespeare then makes the conflicts insoluble all the way down, so the tragedy feels grand and fated, not just a product of accident and misunderstanding. An interesting shift in storytelling technique, and possibly in how we think about conflict. In general, though, it means that I feel I know the characters a lot less well in modern TV than I do in Shakespeare, where they have unpacked their thoughts at length. The silence and dramatic gazes are partly in service of giving the audience a chance to gaze at CG backgrounds and beautiful TV stars–not generally a goal in Shakespeare productions–but I wonder whether it also facilitates the practices of fan culture and fan fiction, defining the characters less well and leaving more of a blank slate for the viewer to imagine the details of personality and motivation, to make the character their own.

My second observation is this: Shakespeare’s Histories are so good! So so good! Even the ones people say aren’t very good are good! My Tor essay explains more, and how to get a hold of them, but I cannot overstate how good the (frustratingly hard to find) Jane Howell productions of Henry VI and Richard III are!

And since they are hard to get a hold of, I want to discuss a few aspects of the Jane Howell productions here, not going on about the acting (absolutely stunning!) or the script and plot of the plays themselves (how can these be considered among his weaker plays?!?!) but about the powerful staging and production choices of this unique performance of the three parts of Henry VI plus Richard III, the four consecutive plays performed and filmed (as they should be!) as a single unit.

How Great is Jane Howell’s Henry!

How Great is Jane Howell’s Henry!

I talked in my essay about the Borgias about how sometimes historical TV can have a conflict between communication and accuracy, in which showing things precisely as they were won’t necessarily communicate successfully to the audience. Another impediment to accuracy is budget, at least in earlier decades when TV did not have the opulent effects and costume budgets that recent historical dramas have enjoyed. Working on a BBC budget in 1982-3, Jane Howell and her team absolutely understood the choice between accuracy and communication, and chose communication.

The costumes are not accurate in materials and construction, but are incredibly accurate in what they get across.

For the costumes of court, the patterns are period but the fabrics, instead of being budget-breaking silks and velvets, are over the top, layering brightly patterned floral upholstery-type fabrics one upon another in an overwhelming way-too-much mass of opulence. The effect is more effective at communicating than accurate period costume would be, since with accurate stuff we would sit back gazing, “Ooooh, pretty… I wish I lived in an era when people wore beautiful clothes,” but instead these costumes communicate a sharper message, “Wow, those are way too much, too opulent… this court life is too lavish and corrupt, it needs to change.” We feel the right things, the foreshadowing of instability and radical transformation, even if these costumes don’t belong in any history textbook.

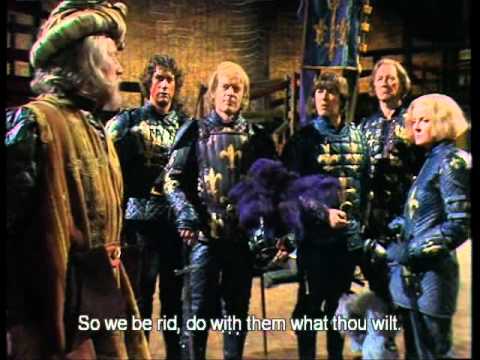

For the armor, the production uses padded armor, almost like one wears for combat sports, brightly painted with the coats of arms of the different sides.

It makes it easy to keep people straight, and see at a glance which nobles are related to which other nobles (like the many cousins of the French royal house above), while keeping everything within budget. And the armor evolves over time, more complex helmets and metal studded surfaces coming in only in the final stages of the Wars of the Roses, invoking the real advances in armor technology that happened in those decades, more effectively than the real armor would since a modern eye is untrained in the subtleties of armor design.

The set too makes virtue of economy. The four films are shot on a single set, a large, colorful, wooden playground, like a kids’ play castle, with turrets, doorways, ladders, climbing nets and connecting bridges, all brightly painted, cheerful reds, yellows, blues. It makes the first battles feel intentionally light and playful, like children playing at knights and kings.

This sets up the viewer’s expectations of a “battle” as light and playful, as the first few conflicts have nothing but wrestling, or a little bit of stage blood smeared across a heroic cheek. But the Wars of the Roses are all about things getting worse, the violence escalating, the destruction mounting. The fourth battle has more blood, more victims. We see bodies. The fifth battle, the sixth, more bodies, gore smeared across young flesh, screams, fire. The violence is still just twenty actors on a wooden set but it feels viscerally more horrible because it escalated from something so light, and is thus more upsetting than many realistic high-budget battle scenes. And the set changes, or rather doesn’t changes. It gets bloodsmeared, smashed by invaders, charred, stained. And they don’t clean it. Scene by scene we watch England ruined:

Like the battles, because the set was so stylized to begin with, its transformation–the ruins and desolation–fells far more absolute and thus far more compelling than if we saw realistic battle effects on real countryside. England has been ruined by these selfish wars, economically, culturally, populations wiped out, and all the unspoken suffering of peasants and townsfolk is present in those charred and blackened sets without adding a word. And then when the wars are finally over, and there is peace, and Richard starts the conflict up again… the horror of it, war coming back again, is so heartbreaking.

Economy also becomes a virtue in–believe it or not–casting, as Jane Howell reuses actors in multiple roles, but not just for efficiency’s sake. She cultivates intertextuality, reusing actors as characters who echo, or ironically reverse, or otherwise connect to their other parts. Here’s one concise example: Henry VI Part 1 begins with three messengers arriving with bad news from France. First Messenger reports that Henry V’s conquests in France have suffered heavy losses, many cities taken by rebelling French, all because the nobility of England are divided into many factions, arguing with each other, unable to unite to send support and direction to the English forces in France. And this herald of the dire consequences of weak rule and factionalism is the actor who (seven hours later) will be Edward IV, the weak and imprudent son of York who will be thrust to the throne by this same factionalism and cause the worst of the civil wars because of his rashness. Then Second Messenger enters with more bad news from France, of enemies uniting, the various French powers drawing together on the far shore–and this actor will be York’s second son, Clarence, who will eventually be a linchpin of that deadly alliance of the French King with Margaret and Warwick which will such a terrible force against war-scarred England. Enter Third Messenger, to tell of a fierce battle between the French and the valiant English Lord Talbot, a small and unhandsome knight but terrifying in battle, who makes a fierce last stand against the overwhelming force, “Hundreds he sent to Hell, and none durst stand him;/ Here, there, and every where, enraged he flew:/ The French exclaim’d, the devil was in arms!” This messenger will eventually be Richard III, and here is describing his own hellish ferocity, and foretelling his own death, which–eleven hours later–precisely matches the details of this first description.

One last detail about the production which is

Henry VI Part 1 begins with the funeral of Henry V, and the Jane Howell version begins with a song (not in Shakespeare’s text) which is a prayer to the ghost of King Henry. The text is period, pre-Shakespeare in fact, probably dating from the reign of Edward IV or Richard III (see a slightly useful reference), and an amazing example of what I have talked about when discussing the Medieval concept of “Grace” and the court of Heaven, how saints were thought of as residents of a royal court, full of “Grace” which (from Latin, gratias) can be translated as “political influence” i.e. having the ear of the King (God/Christ) or Queen (Mary) and the ability to persuade them to help a poor petitioner, just as nobles could persuade earthly monarchs. Look at this text, how it seeks to remind ghostly Henry

Oh Gracious king, so full of virtue

The flower of knighthood, ne’er defiled

Now pray for us to Christ Jesu

And to his mother Mary mild.

In all thy works wast never wild

But full of grace and charity,

Merciful ever to man and child.

Now, sweet King Henry, pray for me.

Oh crowned king, with scepter in hand,

Most mighty conqueror I thee call,

For thou hast conquered, I understand,

A heavenly kingdom imperial,

Where joy aboundeth and grace perpetual,

In presence of the One In Three.

Now of thy grace make me a part,

And, sweet King Henry, pray for me.

Powerful. But even more powerful is the context Jane Howell places it in. This text is not a prayer to Henry V. It is a prayer to Henry VI. Best guess (I haven’t worked in depth on the sources) it would have been written by a supporter after Henry’s death, used secretly under his Yorkish successors, a prayer to the spirit of the famously pious, mild and charitable king, whose conquests are spiritual not Earthly, to be sung or chanted by a former supporter still trapped on the imperfect Earth. Jane Howell places the song at the beginning of Henry VI, foretelling the end, and has it sung by the actor who plays King Henry himself, who is thus singing his own dirge, addressed as a plea of help to his lost, heroic father. Of course, we who just watched the main Henriad (Richard II, Henry IV 1 & 2, Henry V) know that our roguish Prince Hal cannot be described by “in all thy works wast never wild”. This dirge is young King Henry VI’s prayer to the imagined spirit of the father he never knew, a hope for heavenly aid from a pious ghostly king which will not exist until he himself dies and becomes it. Amazing.

And ALL the acting is SO INCREDIBLY BRILLIANT. Especially Richard. And everyone else. And Richard.

Those are just my thoughts on the production, which I really cannot praise enough. For more general discussion of the Henriad itself (and ways to get to see it) see the Tor.com essay.

FYI sadly the easiest way (though it isn’t easy at all!) to get the Jane Howell productions is to buy the complete DVD boxset, hard to get anywhere but Amazon or from the BBC direct) but (if you’re in the US) it requires a Region Free DVD Player as well. Still, it’s a good price for 37 plays, and includes many other treasures including Jane Howell’s Titus Andronicus, and many other great productions and fantastic actors including Derek Jacobi, Helen Mirren, Jonathan Pryce, Zoë Wanamaker, Robert Hardy and others, plus you get to see all the weird plays like Troilus & Cressida that no one puts on. (And Jack Birkett as Thersides is amazing!) Alternately, you can get the individual plays in a special educational-use region 1 DVD format for $39.99 each (alas) from Ambrose Video, an educational video supplier, but getting all four of the Jane Howell sequence costs practically as much as getting the full boxset and the region free DVD player, so you may as well get the box to enjoy the other 33 plays, unless your priority is to have a copy you can lend to friends who don’t have a special player. Jane Howell’s brilliant Richard III also appears in the $70 Region 1 BBC Shakespeare Histories boxset, along with the BBC Histories’ excellent Richard II and okay Henry IV Parts 1 & 2 and Henry V, but the boxset contains only those five plays, skipping the three parts of Henry VI, clearly because the boxset was edited by Iago, who wants to keep us all from having nice things). Thus the most affordable way to have a full region 1 set is to get the Histories box for your two Richards, and the three Ambrose Video discs of Henry VI, which gives you all eight, though I recommend topping it off with (my recommended productions) the magnificent Globe Henry IV Part 1, Part 2, and Henry V, more lively and powerful than the ones in the Histories box.

Final note: Yes, I will give Descartes his day in the Skepticism series soon, I promise, just as soon as I’ve prepped my talk on “Renaissance Biographies of Classical Philosophers” and completed a few more work obligations. Happily the supply of hypothetical pastries is infinite.

15 Responses to “So Much Shakespeare!”

-

I believe you can watch region-locked DVDs on any computer with a DVD drive and a media player that ignores such things, like the freeware VLC Player.

Have you seen Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight? If so, what did you think of it?

-

It is in my “Shakespeare-esque works to be watched soon” stack, along with the Ralph Fiennes Coriolanus, the Globe Faust, and the Patrick Stewart Macbeth, but on top of the stack is the post-apocalyptic Revenger’s Tragedy with Eddie Izzard, Derek Jacobi and Chris Eccleston. Because the 1969 psychedelic tie-dye Ian McKellan version of Marlowe’s Edward II wasn’t sufficiently bizarre!

Now that we’ve seen all of Shakespeare’s plays, the house has the new goal of seeing at least two different productions of all of them. Because the best part really is in all the different powerful things that can be achieved by different versions. Just like good gelato places, each one excels at particular different flavors, and no one production is best at everything.

-

-

I have the BBC Histories box set, and now it is replaced with the BBC full set, I am planning to put it in the Vericon auction.

Also, the Jane Howard Henry VI-Richard III really is wonderful.

-

“First, people don’t say very much in current TV, at least in drama. ”

Too much influence from movies.

There are two distinct aesthetic traditions here.

— The Silent Movie tradition, which became the Movie tradition, which is now taking over TV

— The radio tradition, which became the TV tradition, which is currently in severe retreat (starting around 2000).You can see how they differ. Really very, very few people have made properly *balanced* combinations of sound and visuals — almost every piece can be slotted into “silent movie (with words)” or “radio (with pictures)”. It’s quite extraordinary in fact.

You prefer the material in the radio tradition. So do I.

-

It’s not just radio. Movies-of-plays are usually quite garrulous. E.g. The Lion in Winter, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Glengarry Glen Ross, and even Amadeus.

-

-

If you’re interested in TV at all I would advise looking for the shows from pre-2000 which have “stood the test of time” and are still popular and widely discussed. That’s what I’ve been doing.

Perhaps surprisingly, animated shows currently tend to be talkier and more in the radio tradition.

-

I bought copies of the Jane Howell War of the Roses DVDs from an ebay seller. They’re region free with Korean subtitles. I doubt they’re legit, but if the copyright holders aren’t going to bother to make licensed copies available, needs must. I wanted to see them in preparation for the new Hollow Crown: War of the Roses miniseries, and as excited as I am about seeing Benedict Cumberbatch’s Richard, it’s hard to imagine him beting better than Ron Cook, who’s by far my favorite Richard so far. As for Peter Benson, he IS Henry VI as far as I’m concerned.

-

Very much agreed about Ron Cook, and about Peter Benson. So powerful.

-

-

[…] This was frustrating. Ada Palmer puts in her finger on exactly the problem I had in her discussion of Shakespeare compared to current television: […]

-

This recent Big Idea on Scalzi’s site made me think of this post:

http://whatever.scalzi.com/2016/09/07/the-big-idea-robin-talley/