Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful

I was recently interviewed for a piece in the Times on why the philosophy of stoicism has become very popular in the Silicon Valley tech crowd. Only a sliver of my thoughts made it into the article, but the question from Nellie Bowles was very stimulating so I wanted to share more of my thoughts.

To begin with, like any ancient philosophy, stoicism has a physics and metaphysics–how it thinks the universe works–and separately an ethics–how it advises one to live, and judge good and bad action. The ethics is based on the physics and metaphysics, but can be divorced from it, and the ethics has long been far more popular than the metaphysics. This is a big part of why stoic texts surviving from antiquity focus on the ethics; people transcribing manuscripts cared more about these than about the others. And this is why thinkers from Cicero to Petrarch to today have celebrated stoicism’s moral and ethical advice while following utterly different cosmologies and metaphysicses. (For serious engagement with stoic ontology & metaphysics you want Spinoza.) The current fad for stoicism, like all past fads for stoicism (except Spinoza) focuses on the ethics.

Thinking Spots: Stoic Metaphysics and Ontology

Stoic ontology and metaphysics are sufficiently awesome that I must give it a couple paragraphs before I move to the ethics, though the ethics are the core of its popularity today. Stoics were monists; if dualists like Plato and Descartes believe there are fundamentally two things (matter and non-matter, for example), monists believe there is fundamentally one thing. Not just one category of thing (Epicurean atomists, for example, think there is only one kind of thing: atoms) but actually one single thing. The stoics posited that the universe is one enormous contiguous single object. Different parts of it manifest different qualities, but are the same. Just as polkadot fabric may manifest blueness here and whiteness there but remains the same object, so the part of the universe which is your hand manifests firmness and warmth and opacity, and the part which is the air manifests softness and transparency, but they are the same object. And when you seem to move your hand, in fact there is no motion, rather the part of the universe that was manifesting the transparency and softness of air before is manifesting the firmness and opacity of arm now and vice versa. Think of the pixels on a screen: what seem to be objects moving are in fact different parts of the screen changing color (i.e. changing quality) in sequence, creating the illusion of motion whereas in fact there is only variation in the surface of an object. (This is the stoic solution to Zeno’s paradoxes of motion discussed here). The stoic living universe is thus somewhat like the skin of a mimic octopus, able to seem to be become a myriad different things while it remains one. And in addition to blueness, and whiteness, and opacity, and warmth, other attributes the universe manifests more in some places than others include what we would call in modern terms sentience, self-awareness, and reason–thus the human being is a spot of sentience against a background of less sentient substance, like a white spot on blue. But, the stoics argue, any property which is possessed by the part is possessed by the whole, so while sentience and reason are concentrated in the spots which are living humans, the whole thing is a vast, intelligent, rational whole, and when we die we merge back into it. Thus there is no individual immortality, but we are all part of something greater which is eternal, wise, and infinite.

Stoic ontology and metaphysics are sufficiently awesome that I must give it a couple paragraphs before I move to the ethics, though the ethics are the core of its popularity today. Stoics were monists; if dualists like Plato and Descartes believe there are fundamentally two things (matter and non-matter, for example), monists believe there is fundamentally one thing. Not just one category of thing (Epicurean atomists, for example, think there is only one kind of thing: atoms) but actually one single thing. The stoics posited that the universe is one enormous contiguous single object. Different parts of it manifest different qualities, but are the same. Just as polkadot fabric may manifest blueness here and whiteness there but remains the same object, so the part of the universe which is your hand manifests firmness and warmth and opacity, and the part which is the air manifests softness and transparency, but they are the same object. And when you seem to move your hand, in fact there is no motion, rather the part of the universe that was manifesting the transparency and softness of air before is manifesting the firmness and opacity of arm now and vice versa. Think of the pixels on a screen: what seem to be objects moving are in fact different parts of the screen changing color (i.e. changing quality) in sequence, creating the illusion of motion whereas in fact there is only variation in the surface of an object. (This is the stoic solution to Zeno’s paradoxes of motion discussed here). The stoic living universe is thus somewhat like the skin of a mimic octopus, able to seem to be become a myriad different things while it remains one. And in addition to blueness, and whiteness, and opacity, and warmth, other attributes the universe manifests more in some places than others include what we would call in modern terms sentience, self-awareness, and reason–thus the human being is a spot of sentience against a background of less sentient substance, like a white spot on blue. But, the stoics argue, any property which is possessed by the part is possessed by the whole, so while sentience and reason are concentrated in the spots which are living humans, the whole thing is a vast, intelligent, rational whole, and when we die we merge back into it. Thus there is no individual immortality, but we are all part of something greater which is eternal, wise, and infinite.

Stoicism was likely influenced by Buddhism through contact with India during the wars of Alexander the Great, and shares a lot with Buddhism: the whole universe is one vast, living, divine whole. Life is full of suffering, but that suffering is a path to understanding a larger good. And there is a universal justice on the large scale beyond what a human from our limited P.O.V. can understand. In Buddhism this is karma, while for the stoics it is Providence, the same concept of Providence that Christianity later borrowed, which argues that everything in the world which seems bad is actually good in a way we cannot fully understand because of our limited perspective. It is as if we are a fingertip; we cannot understand why we must suffer the evil of being repeatedly banged against a hard, unyielding surface, because we don’t have the means to understand that the larger organism is typing up a blog post about stoicism, but if we did have the means to understand we would recognize that it’s worth-it on the large scale. The stoic justification for claiming the universe is perfect is the patterns we see in nature: trees have roots to drink the water they need, woodpeckers that eat bugs have beaks the shape they need to be, woodland animals have woodland camouflage, desert animals have desert camouflage, everything fits together in a vast, functional whole which (without Darwin to offer an alternative) the Greeks agreed implied intelligence, either in a creator (Aristotle’s demiurge), a source (Plato’s Good), or, for the stoics, the universe itself.

The stoics also argued (followed by some Christian thinkers) that there is no self-determination. We will all end up going where the Plan will have us go no matter what, but the one thing we do have power over is our own inner responses to the path fate gives us: do we curse, complain, fight, shake our fists at the heavens, or do we ascent, accept, relax, and gaze in happy awe on the vastness of which we are a part? A classic stoic image (and after this I’ll turn to ethics and the tech crowd) is that the human being is like a dog tied behind a cart. The cart is going somewhere, and there is absolutely nothing the dog can do to change the course the cart will take. The dog has freewill only in one thing: the dog can fight, snarl, tug at the collar, gnaw on the rope, dig its claws into the dirt until it bleeds, and exhaust itself with fighting, or it can trot along contentedly and trust the driver.

An Action Ethics

A lot of the surviving stoic writings are maxims, short pieces for contemplation designed to help you dwell less on bad things that are happening, sometimes more imagery than argument. Imagine–for example–that life is like being a guest at a banquet. Platters are being passed around and people are reaching out and taking what is offered them. Some platters come to you and you take of them–other platters never make it to you, or are empty when they do. But you are a guest, these things were not yours, they were offered as gifts, so you have no reason to be angry that you can only taste some of them–better to enjoy the platters that do reach you, and remember that the host who offered them is kind.

This is where stoicism serves very much like a self-help book, or more generally as philosophical therapy, which is what classical philosophies largely aimed to provide. Stoicism’s recommendations for how to resist pain are exquisite, as in this example from the Meditations. And the metaphysics crops up mainly as a way to justify the advice:

XXV. What a small portion of vast and infinite eternity it is, that is allowed unto every one of us, and how soon it vanisheth into the general age of the world: of the common substance, and of the common soul also what a small portion is allotted unto us: and in what a little clod of the whole earth (as it were) it is that thou doest crawl. After thou shalt rightly have considered these things with thyself; fancy not anything else in the world any more to be of any weight and moment but this, to do that only which thine own nature doth require; and to conform thyself to that which the common nature doth afford.

An Ethics for the Rich and Powerful

An Ethics for the Rich and Powerful

At this point I want to remind the reader that I personally love stoicism. It’s gorgeous. It’s brilliant. Revisiting it I find it always challenges assumptions, pushes me to hold myself to high standards, gives me new ideas to chew on. Its major texts, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, are ones I love to teach, love to revisit, love to grapple with again and again. I will continue to praise, and teach, and write about, and read, and make use of stoicism all the days of my life. But…

The new popularity of stoicism among the tech crowd, and also on Wall Street which is another place that’s been reading and naming things after stoics recently, is strikingly similar to stoicism’s popularity among the powerful elites of ancient Rome. In Hellenistic Greece, stoicism had been one of several different popular philosophical schools, along with Platnonism, skepticism, Pythagoreanism, cynicism, Aristotelianism, Hedonism etc. (Quick tip: names of philosophical systems are generally capitalized when named after people, not capitalized when named after other stuff, as in cynicism from cynos, dog; stoicism from stoa, porch, where the first stoics held their classes.) And like the rest of these ancient schools, stoicism focused on eudaimonia, i.e. happiness or the good life, the idea that the purpose of philosophical study was not primarily to understand everything, or to achieve power through knowledge, but to achieve personal happiness, usually through inner tranquility and armoring the soul against the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune (see my essay on eudaimonia for more.) Stoicism was one of a number of methods to attempt this, so like all ancient schools it fulfilled the roles of a self-help book and Science 101 textbook rolled into one.

But in Rome stoicism surged in popularity compared to all the other systems, because it was the one Greek ethics which worked well for the rich and powerful. Other schools like Platonism, cynicism, and Epicureanism warned followers that participation in politics and the pursuit of wealth, power, or honor would only lead to stress and risk, and were incompatible with happiness. Epicurus said the happy life was found by leaving the political urban world to sit in a secluded garden, eating a simple meal while conversing with good friends. Cynicism advocated the more extreme step of renouncing personal property and living like a stray dog scrounging beside the road, which has no fear of being robbed or losing its status because it has nothing to lose. The Pythagoreans and many other sects lived in isolated communities not unlike monastic orders, and used strict diets, ascetic dress codes, even vows of silence. Plato too specified that the philosopher kings of the republic are made unhappy by the stress of having to rule, and a number of ancient figures even used the stress of rule to argue that the gods can’t possibly hear and act on human prayers or else the gods would be perpetually harassed and unhappy.

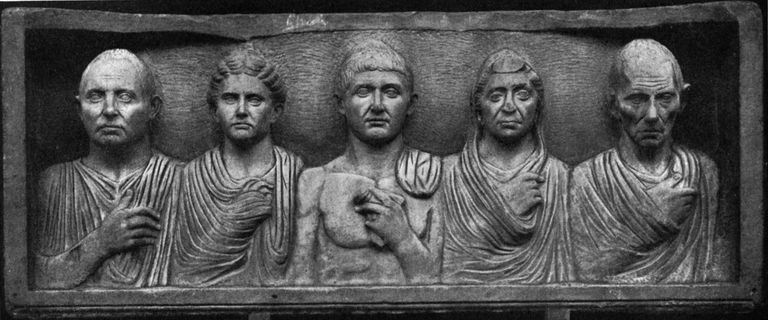

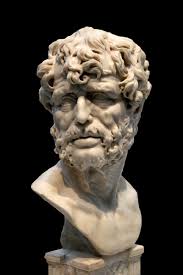

Stoicism, on the other hand, stressed the idea that everyone is part of a large perfect whole and thus that it’s everyone’s duty to fulfill the role Fate allots. In the ordering of nature the woodpecker should peck, the deer should graze, the bee should pollinate, and the wolf should hunt and kill. We too as humans have a duty to fulfill our roles, be that as servant, merchant, slave, or king. Some stoic authors were slaves themselves, like Epictetus author of the beautiful stoic handbook Enchiridion, and many stoic writings focus on providing therapies for armoring one’s inner self against such evils as physical pain, illness, losing friends, disgrace, and exile. But other stoic philosophers were great leaders of states, including leading statesmen like Cicero and Seneca, and the Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Stoicism caught on among Roman elites because it was the one form of philosophical guidance that didn’t urge them to renounce wealth or power. Politics is stressful, but rather than giving it up to live like a monk or a dog, stoicism says you should continue the hard work seek to attain an inner attitude in which you will not suffer misery when you do fail, when you do lose the election, face the criticism, suffer the setback, feel the blows of fortune. Stoicism alone recommended inner detachment, not walking away. For Roman patrician statesmen with long family traditions of political leadership, walking away from civic participation was a non-starter (especially since Roman ancestor worship meant that achieving a name in politics was also a religious duty which your very afterlife depended on!). Stoicism finally offered a philosophical ethics useful to the statesman, which is why Cicero–a skeptic who engaged with many sects of philosophy–favors it in his dialogs more consistently than any other sect (this may not sound like a strong endorsement but is a high a very high bar for Cicero. And Cicero is a very big deal).

Thus, turning to the questions that Nellie asked me for her article, when I see a fad for stoicism among today’s rising rich, I see a good side and a bad side. The good side is that stoicism, sharing a lot with Buddhism, teaches that the only real treasures are inner treasures–virtue, self-mastery, courage, charity–and that all things in existence are part of one good, divine, and sacred whole, a stance which can combat selfishness and intolerance by encouraging self-discipline and teaching us to love and value every stranger as much as we love our families and ourselves. But on the negative side, stoicism’s Providential claim that everything in the universe is already perfect and that things which seem bad or unjust are secretly good underneath (a claim Christianity borrowed from Stoicism) can be used to justify the idea that the rich and powerful are meant to be rich and powerful, that the poor and downtrodden are meant to be poor and downtrodden, and that even the worst actions are actually good in an ineffable and eternal way. Such claims can be used to justify complacency, social callousness, and even exploitative or destructive behavior.

Seen in the best light, a wealthy person excited by stoicism is seeking a philosophy that helps the mind resist greed and the capitalist rat race and offers a wiser perspective and inner happiness; seen in the worst light it can be a tool for justifying keeping one’s wealth and power and not trying to help others. In that sense it reminds me of the profession of wealth therapists who help the uber-wealthy stop feeling guilty about spending $2,000 on bed sheets or millions on a megayacht. Wealth does come with real emotional challenges, but as society calls more and more for fundamental reform to close the wealth gap and reduce the power wielded by the 1%, cultivating a pro-status-quo attitude can also be a way to deflect pressure to try to address society’s ills.

Seneca, an author I absolutely love, wrote exquisite maxims about selflessness and virtue which have been backbones of moral and political education for two millenia. So powerful are his arguments that Petrarch, when comparing the strengths of the ancient Romans and ancient Greeks in different arts (Homer v. Virgil in poetry, Demosthenes v. Cicero in oratory, Thucydides v. Livy in history etc.) concluded that Seneca alone makes the Latins wholly superior to the Greeks in matters of ethics. Seneca also risked his life trying to curb the tyranny of Nero, and eventually died for it. But for all Seneca’s powerful advice about the big picture and the meaninglessness of wealth, he was also a slave-owner who, when alerted that his male slaves were sexually abusing his female slaves, set up a brothel in his estate so he could make his male slaves pay him for the privilege of abusing his female slaves–not quite the behavior we imagine when Seneca says money is meaningless and all living beings are sacred. But stoicism urges us to turn our critical eye inward and improve ourselves, not to turn it outward and improve our worlds. It gave Seneca the courage and resolve to face the danger of Nero’s deadly whims day by day in order to do his duty to the Roman political elite, but it didn’t encourage him to question his world order.

Stoicism is an intellectually rich and stimulating system, and wonderful therapy against grief, against dwelling on setbacks, and against getting caught up in the chase for fame and fortune and the blinders of the rat race. It reminds us to zoom out from a world of praise, and blame, and status, and cruel things people said on Twitter, and the competition to see made the most sales, or had the most hits, or got the largest raise, all things which can be genuinely emotionally devastating if we let ourselves get too caught up in them. In all those ways stoicism is a great match for Silicon Valley, for Wall Street, also for my world of academia and tenure and their stresses and injustices. It’s also a great match for congresspeople, authors, journalists, actors, entrepreneurs, everyone whose life contains stresses and setbacks and moments when we need help to let us to take a deep breath and let it go. But Cicero was not Voltaire, and did not look at the evils and injustices around him and conclude that he should wield his power to make a fundamentally better world–he focused only on coping with the world as it already was, and fulfilling his duties within it. Stoicism predates the concept of human-generated progress by more than a millennium. It doesn’t teach us how to change the terrible aspects of the world, it teaches us how to adapt ourselves to them, and to accept them, presuming that they fundamentally cannot be fixed. But we have two millenia more experience than Seneca. We know many of life’s evils can’t be fixed, but we also know, with human teamwork and the scientific method and a dose of Bacon and Voltaire, some of them can.

That’s why when I hear that rich, powerful people are into stoicism I think it’s great that people are excited by the idea that we should hold all life sacred and look for meaning beyond wealth and worldly power. I think it’s a great philosophy for anyone, and certainly for those who need help zooming out from a high-stress, high-competition world to think about the human and humane big picture, and to pay more attention to self-care, and loving others. But it also makes me a little wary. Because I think it’s important that we mingle some Voltaire in with our Seneca, and remember that stoicism’s invaluable advice for taking better care of ourselves inside can–if we fail to mix it with other ideas–come with a big blind spot regarding the world outside ourselves, and whether we should change it. An activist can be a stoic–activism absolutely needs some way to help cope with the pain when we pour our hearts and hours into trying to help someone, or pass new legislation, or resist, and fail. For such moments, stoicism is a precious remedy against despair and burn-out, but it doesn’t in itself offer us the impetus toward activism and resistance in the first place. That we need to get from somewhere else.

41 Responses to “Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful”

-

I’m so happy to see a new entry on your blog! Very interesting and relevant read too!

I have a question regarding the anecdote about Seneca setting up a brothel with/for his slaves. Obviously, looking at it with today’s morals that is an incredibly awful thing to do (as is owning slaves in the first place), and it does contrast with the idea that all living beings are sacred. But I don’t really have a good picture of how people in Antiquity thought. As you said, the concept of human-driven progress hadn’t been invented. Are there philosophers in the Antiquity who would have considered Seneca’s actions morally wrong? If so, did they also object to owning slaves or just the making money from sexual abuse part?

-

Did Seneca consult his slaves, male or female, before deciding?

-

The Persians didn’t practice slavery Contrary to what “300” would tell you, but the concept of slavery was also very different from slavery in north america which was fucking brutal in comparison. You find the rights of slaves dictated under the Hammurabi code, including marriage rights and inheritance. Even upwardly mobile slaves who became generals in Roman armies. You have to recall their are even bits where the most powerful people in some empires are slaves The term Vizer is egyptian for a slave in management sometimes the Vizers had more money and power then free men. He could call the guards and have the free thrown to the crocodiles.

-

-

I stopped reading when the phrase “stoicism got influenced from budism during Alexander the great travel”. What a pile of crap! The author is definitely historically challenged. Stoicism predated Alexander by a few centuries at least. That’s usually what happens when a good thing starts to be s fad. Too many pseudo philosophers aching to publish

-

When something starts existing and when it is influenced by outside ideas are two different concepts.

-

Yeah, stoicism changed over time and was influenced by other philosophies, just like every other philosophy has been.

-

-

Stoicism was influenced very much by Buddhist thought. Read Christopher Beckwith’s Greek Buddha.

-

-

Zeno of Citium (c.366-265) BC founded the stoic school, and is recorded as having begun teaching in 300 BC, more than 30 years after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC.

https://www.ancient.eu/Zeno_of_Citium/Like Epicureanism, stoicism is one of the rich body of Hellenistic philosophies whose innovative complexity was stimulated and enabled by the new interconnection of cultures created when Alexander’s conquests brought the Mediterranean and south/central asian worlds into greater contact, and disseminated the Greek language which began to function as a broadly-intelligible common shared second language of trade and cultural exchange, crossing what had been firm linguistic barriers.

Stoicism did have earlier Greek roots too, however, most notably the cynic school, which predated Zeno, having been advanced by Antisthenes, a student of Plato and peer of Socrates, though the most famous cynic, Diogenes of Athens, was a contemporary of Alexander.

For more on the specific dates in the history of stoicism and its evolution and dissemination, see “The Routledge Handbook of the Stoic Tradition,” ed. John Sellars. New York: Routledge, 2016. I contributed the Renaissance chapter.

-

Thanks for posting this! I liked the NY Times article—and I learnt a lot while reading it—but could not help being disappointed that it is so short, with so few direct quotes from you there (honest cultural question here: is this routine in English-language media? From (continental) Europe, I’m used to “interviews” being long rambling transcripts of conversations which may easily take up half a page or more in a newspaper, with the interviewer either adding either nothing or just a short introduction to who is being interviewed and why).

So I’m very glad you expanded on it! (and you are right, the metaphysics are *awesome*, I’d never even heard of them before!)

One question though, which sprang to mind while reading this: the argument with the trees and woodpeckers, that everything fits together; it reminded me intensely of Voltaire having Pangloss say stuff like “men have noses, therefore we have glasses”, and the increasingly absurd justifications he gives later about how e.g. the earthquake of Lisbon needed to happen. Was Leibnitz’s optimism influenced by stoicism, and what did Voltaire think of stoicism?

-

Very interesting, thanks. I had 1 philosophy course in college and all I remember from it is Nietzsche – ugh! I’ve been slowly and frustratingly studying economics/abundance since I retired 6 years ago. Should probably add some philosophy. But, so much good new SF to read! Currently 53 unread books in my iPad 🙁

-

[…] Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful 2 by fanf2 | 0 comments on Hacker News. […]

-

Interesting article. I first learned of Stoicism on the Mr. Money Mustache blog. I don’t think he mentions the whole predestined bits at all, instead focusing on the parts about limitting your consumption/desires and being happy while doing so. Given the number of techie readers he has I wonder how much of Stoicism’s resurgence amongst that crowd traces back to him? Would love to hear your thoughts on his article. http://www.mrmoneymustache.com/2011/10/02/what-is-stoicism-and-how-can-it-turn-your-life-to-solid-gold/

-

-

[…] Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful 3 by fanf2 | 0 comments on Hacker News. […]

-

[…] Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful 3 by fanf2 | 0 comments on Hacker News. […]

-

[…] Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful 3 by fanf2 | 0 comments on Hacker News. […]

-

[…] Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful 4 by fanf2 | 0 comments on Hacker News. […]

-

Nice work on this.

I have to disagree on when you say that Stoicism borrowed from Buddhism and Christianity borrowed from Stoicism.

It is not as much borrowed as they are seeds of the Logos mutually discovered.

-

Isn’t Christianity’s borrowing from Stoicism (and other Greek philosophies) pretty well-attested? Like I think most of the major medieval theologians explicitly cited classical sources when writing. I don’t think Ada Palmer is just asserting this borrowing because one happened after the other; I think it’s right there in the text.

-

-

[…] Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful – Ex Urbe […]

-

I noticed you skipped the Aristotelian school in your rundown of hellenistic philosophical schools. Any particular reason for that? I could see how the Romans might have scoffed at Aristotle’s insistence that virtue alone, though the chief good, is not sufficient for the best life, but it seems to me that Aristotle’s emphasis on Virtue *and* worldly goods might be especially appealing to modern people. Why do you reckon Aristotle hasn’t made it to fad status yet? Insufficient publicity?

-

[…] Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful […]

-

[…] Ada Palmer, “Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful” […]

-

“But for all Seneca’s powerful advice about the big picture and the meaninglessness of wealth, he was also a slave-owner who, when alerted that his male slaves were sexually abusing his female slaves, set up a brothel in his estate so he could make his male slaves pay him for the privilege of abusing his female slaves”

Can you provide a historical source for that accusation against Seneca?

-

Exurbe, thanks for sharing the dangers and jewels of stoicism. I like to think of myself as a very crude student of it, certainly I believe the human race is in a process of understanding the principles and current state of universe, and as such it will take many generations until we realize what the ideal status of universe should be and what can we do to “fix” it. Meanwhile, stoicism is my personal way to go 🙂

-

When you say stoicism appeals to the rich and powerful, do you mean stoics are actually reading stoic philosophy books, specifically stoic ethics books rather than metaphysics? Thanks!

-

[…] die Ideengeschichtlerin und Science-Fiction-Autorin Ada Palmer, hat sich in einem aktuellen Blogbeitrag kritisch mit der aktuellen Stoa-Mode in den USA und vor allem im Silicon Valley auseinandergesetzt. […]

-

Grant me the Stoïcism to deal with the things that can’t be changed for the better, the left-anarchism to change for the better the things that can, and the data and processing cycles and power needed to tell the difference.

-

Best comment yet!

-

-

-

Neither rich nor powerful (nor privileged, no Patrician), but Stoicicms, especially Sharon Lebell’s adaptation of the Enchiridion, “The Art of Living”, helped me survive my last several years of work before retirement. Specifically, after 40 years of dealing with management, I was us… ‘disgruntled’ and came close to snapping. Epictetus in the morning with coffee helped. A lot.

-

Any pain-killer can be abused.

-

Thank you for this! I too am taken with stoicism and appreciated the critical perspective. One critique I have with upper class (white) culture is its tendency to see making statements (mostly about oneself) as the best way to address problems in the empirical world. Want racism to go away? Tell everyone you are against it and don’t tolerate any racist speech. We fight racist expressions and see that as the same thing as fighting racism. Of course those two things are not in opposition, and fighting against expressions of racism is not bad, but it may not yield the most good, and it doesn’t cost much. Sending your child to a public school with a diverse racial, ethnic, soci0-economic group of students, instead of a private school which is totally against racism but also just so happens to give your child the best chance to “succeed” later in life, would probably feel a lot riskier. This emphasis on speech–on getting the symbols right–and letting the rest follow from that seems somehow related to the “what is up to us” and “what is not up to us” that I read in Epictetus. Ultimately, we often act today as if the ultimate reality is internal, what we feel and experience, and that is more important than the empirical world around us. As it turns out, addressing these things tends to be relatively cost free–at least in a material sense–and offers us personal benefits.

Again, thanks!

-

Of course Christianity does not say anything as vulgar as the bad is good, not in any way, though hypocrites who called themselves Christian have. And the reason Voltaire had a different view from the stoics was that he was Christian, i.e., his moral views were completely shaped by Christianity. Today we are almost all good secularized Christians, as Nietzsche pointed out.

-

Well said. I speak as someone who has read Marcus Aurelius, and a bit more, and seen some merit in stoicism, but does not fully accept it; you have articulated the case against pure stoicism better than I could have done.

P.S. We met at Balticon a few years ago. I hope your chronic pain problems are not too serious at the moment, and that they may in due course go away.

-

Thanks for such a well written and thoughtful article. I’m not familiar with this blogspot but I would have liked to be in one of your courses.

I think you may be mistaken about Seneca. I’ve heard that before, back when electricity was invented, and wonder where would slaves have gotten money to pay with~. Even so wouldn’t this be placing value on something that seemed to have none – a consequence where there had been none, sort of a choice to be made.

I thoroughly enjoyed this. I am subscribing to ex Urbe- used to have a friend Al Erber , German guy but probably not the same.Thanks

Brendan

-

-

[…] CICERO – NOT ILLINOIS. Ada Palmer dives into “Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful” at Ex […]

-

Ada, very nice article. I have an invitation to comment or interject your opinion. Our perception of the he world and it’s composition is primarily if not wholly understood and filtered through a narrative consciousness. ( a story that we tell ourselves about who we are and what t world is and is about). This story typically develops around a central idea that we are basically good and or capable of being made good wether through our actions or the actions of another and we understand enough of the world around us to be ethically justifiable in our actions. But our narratives are essentially devoted of any reality no matter how sophisticated and nuanced they may be. Much like the wealthy Roman elite chose stoicism because it provided justification for their narrative which they wrote about how they are good people and understand what’s going on in the world. Cannot this rightly be pointed at every human who has ever lived. Essentially it’s our inner narrative and thus our circumstances which define our ethics Not or ethics which defines our circumstances. We humans choose the ethical system (stoicism, utilitarianism, Buddhism, Catholicism, etc…) which best justifies us in our narrative self. If our circumstances change we adapt our ethics to match the new narrative. Politicians do this all the time. Whichever party is in majority uses utilitarian ethics to justify sacrifices that need to be made. The minority party will use value or deontology in order to delegitimize. The party in power. Everyone does it all the time.

-

Exurbe, Thank you for this brilliant essay. It teaches me that most everything that’s wise and noble has come before us—surprise. When you invoked Voltaire, I became overwhelmed, as now I realize that one of my favorite contemporary philosophers, Ken Wilber, is in large part (not entirely, but still) an amalgam of Stoicism and Voltaire, just like you recommend. At least as modern philosophers go, I relate most readily to Wilber. I’d love to hear your comments on Wilber in this context.

Meanwhile, I’m now living in France, and it is my goal (might take a while) to read Voltaire in his native tongue. Stoicism help in that regard: It’s my destiny, so why not?

-

[…] Palmer, Ada. “Stoicism’s Appeal to the Rich and Powerful.” Ex Urbe (blog). Entry posted March 27, 2019. Accessed August 15, 2021. https://www.exurbe.com/stoicisms-appeal-to-the-rich-and-powerful/. […]

-

[…] su blog Ex Urbe, la historiadora Ada Palmer, experta en el pensamiento estoico y profesora en la Universidad de […]

-

[…] of providentialist thinking which let one abdicate a sense of personal responsibility (the new fad for stoicism is one) but pursuing personal purity has the bonus of making it feel like you actually are taking […]