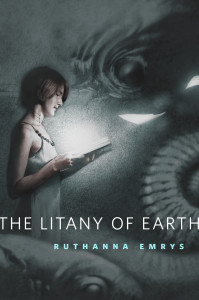

Discontinuity and Empathy: a non-review of “The Litany of Earth” by Ruthanna Emrys.

On the one hand, I have been looking forward for ages to reading and then writing something about “The Litany of Earth,” an amazing novelette by Ruthanna Emrys, acquired for Tor.com by editor Carl Engle-Laird. But on the other hand I personally usually dislike reading reviews, at least traditional reviews of things I have already decided to read. When a reviewer tells me about what I’m going to experience and what excellent things the author is going to do, it disrupts the reading process for me, makes the things mentioned in the review stand out too boldly, interfering with the craftsmanship of a good story in which the author has taken great pains to give each beat just the right amount of emphasis, no more, no less. The memory of the review in my mind makes it like a used book which someone has gone through with highlighter, which can be fascinating as a window on a fellow reader, and delightful for a reread, but it isn’t what I want on first meeting a new text, which in my ideal world consists of me, the reader, placing myself wholly and directly in the hands of the author, with the editor’s touch there too to help spot us along the way. I do not need a co-pilot. And it is more of a problem, for me at least, with short fiction than with long fiction since the review could be half as long as the story and weigh me down with nearly as much weight as the whole thing carries. So, today I have set myself the challenge of writing a review, or non-review, of “The Litany of Earth” that isn’t a co-pilot, or a highlighter, and does as much as possible to get across the story’s strengths and the power of the reading experience while doing my best not to change the relative weight of anything in the story, make anything jump out too boldly, leaving the craftsmanship as untouched as it can be.

I have a seven step plan. (Personal rule: anything with three or more steps counts as a plan. Also, “Profit” is not a step, it’s an outcome, and does not count toward your total of three.)

- Recommend you go read “The Litany of Earth” now before I can spoil anything.

- Talk amorphously about things the story is doing with structure and world-canon, talking more concretely about a few other pieces of fiction that have done somewhat similar things.

- Ramble about Petrarch.

- Ramble about Diderot. Dear, dear Diderot…

- Urge you to read “The Litany of Earth” again, last chance before I get out my highlighter.

- Talk about “The Litany of Earth” directly.

- Sing.

Step One: I strongly recommend that you go read “The Litany of Earth” right now. It’s free online, and if you read it now you won’t be stuck with an intrusive co-pilot even if I do fail in today’s challenge of writing a non-review.

Step Two: Talk amorphously, and compare the story to other works of fiction.

One of the unique literary assets of current fiction is the proliferation of familiar but elaborate and thoroughly developed fictional worlds which authors can step into and use for new purposes. There have always been such worlds as long as there has been literature. Arthuriana is my favorite pre-modern example, a complex and well-populated world rich with explorable relationships and flexible metaphysics ready to be elaborated upon and repurposed. Geoffrey of Monmouth and Thomas Malory and Petrarch and Ariosto and the traditional artists in Naples who decorated (and still decorate) street vendor wagons with Arthur’s knights each repurposed Arthuriana just like Marion Zimmer Bradley and and Monty Python and Gargoyles and Heather Dale and Babylon 5 and the endlessly hilarious antics of the BBC’s Merlin. Each of the later authors in the genealogy has taken advantage not only of the plot, setting and characters but knowing that readers have genre expectations.

One of the unique literary assets of current fiction is the proliferation of familiar but elaborate and thoroughly developed fictional worlds which authors can step into and use for new purposes. There have always been such worlds as long as there has been literature. Arthuriana is my favorite pre-modern example, a complex and well-populated world rich with explorable relationships and flexible metaphysics ready to be elaborated upon and repurposed. Geoffrey of Monmouth and Thomas Malory and Petrarch and Ariosto and the traditional artists in Naples who decorated (and still decorate) street vendor wagons with Arthur’s knights each repurposed Arthuriana just like Marion Zimmer Bradley and and Monty Python and Gargoyles and Heather Dale and Babylon 5 and the endlessly hilarious antics of the BBC’s Merlin. Each of the later authors in the genealogy has taken advantage not only of the plot, setting and characters but knowing that readers have genre expectations.

In the early 1500s when Ariosto began his chivalric and slightly-Arthurian verse epic Orlando Furioso he took advantage of the fact that readers already associated the topic with epic works and grand tourneys and knights and ladies and courtly-love adultery, baggage which let him write a massive and endless rambling snarl of disjointed and fantastic adventurousness so unwieldy that traditional epic structure is to Orlando Furioso as a sturdy rope is to the unassailable rat’s nest of broken headphones and cables for forgotten electronics that I just fished out of this bottom drawer.  No reader, not even in 1516, would put up with it without the promise of Arthurian grandeur to make its massive scale feel appropriate. (I will also argue that the BBC Merlin, for all its tomatoes and giant scorpions, has not actually done anything quite so unreasonable as the point when Ariosto has “Saint Merlin” rise from his tomb to deliver an endless rambling prophecy about how awesome Ariosto’s boss Ipollito D’Este is going to be. Fan service long predates the printing press.) In a more recent continuation of this tradition, modern Arthurian adaptations have given us the previously-silenced P.O.V.s of women, of villains, of third-tier characters, and in some sense it’s quite modern to think about P.O.V. at all. But even very old adaptations take advantage of how not just setting but genre is an asset usable to get the reader to follow the author to places a reader might not normally be willing to go. And, of course, in more recent versions authors have taken advantage of exploring silenced P.O.V.s to critique earlier Arthurian works and their blind spots, as a way of reaching the broader blindnesses and silencings of the past stages of our own society that birthed these worlds.

No reader, not even in 1516, would put up with it without the promise of Arthurian grandeur to make its massive scale feel appropriate. (I will also argue that the BBC Merlin, for all its tomatoes and giant scorpions, has not actually done anything quite so unreasonable as the point when Ariosto has “Saint Merlin” rise from his tomb to deliver an endless rambling prophecy about how awesome Ariosto’s boss Ipollito D’Este is going to be. Fan service long predates the printing press.) In a more recent continuation of this tradition, modern Arthurian adaptations have given us the previously-silenced P.O.V.s of women, of villains, of third-tier characters, and in some sense it’s quite modern to think about P.O.V. at all. But even very old adaptations take advantage of how not just setting but genre is an asset usable to get the reader to follow the author to places a reader might not normally be willing to go. And, of course, in more recent versions authors have taken advantage of exploring silenced P.O.V.s to critique earlier Arthurian works and their blind spots, as a way of reaching the broader blindnesses and silencings of the past stages of our own society that birthed these worlds.

“Is ‘The Litany of Earth’ Arthuriana?” you may wonder. No. It uses a different mythos. I bring up Arthuriana in order to remind you of the many great things you’ve seen humans create by using and reusing a familiar collective fiction, and in order to reinforce my earlier claim that one of the great assets of current fiction is that we have many, many such worlds. If pre-modern Earth had several dozen rich, lively, reusable mythoi and epic settings, the 20th century has added many, many more in which good (and campy) things have and can be done. Star Trek, Sherlock Holmes, Gundam, the massive united comics universes of Marvel and DC, these each provide as much complexity and material for reuse and reframing as the richest ancient epics, more if, for example, you compare the countless thousands of pages of surviving X-Men to the fragile little Penguin Classics collections of Eddas and fragmentary sagas which preserve what little we still have of the Norse mythic cosmos. Marvel’s universe, and DC’s too, have a fuller population and a more elaborate and eventful history than any mythos we have inherited from antiquity, and my own facetious in-character reviews of the Marvel movies are but the shallowest tip of what can be done with it.

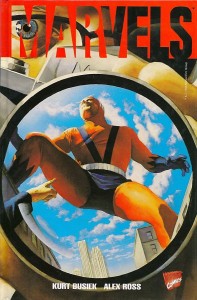

The specific case of this kind of rich reuse whose parallels to “The Litany of Earth” are what brought me down this line analysis comes from the Marvel comics megaverse, the unique and skinny stand-alone Marvels, by Kurt Busiek, illustrated by Alex Ross. What it does with the narrative possibilities of the Marvel universe is very much worth looking at even if one doesn’t care a jot about comics.

The specific case of this kind of rich reuse whose parallels to “The Litany of Earth” are what brought me down this line analysis comes from the Marvel comics megaverse, the unique and skinny stand-alone Marvels, by Kurt Busiek, illustrated by Alex Ross. What it does with the narrative possibilities of the Marvel universe is very much worth looking at even if one doesn’t care a jot about comics.

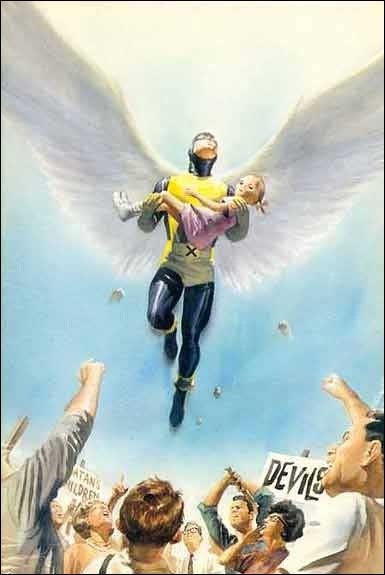

Described from the outside and ignoring, for a moment, that these are comic books, the Marvel universe presents us with an Earth-like alternate history in which disasters–supernatural, alien, primordial, divine–have repeatedly threatened Earth, the universe, and, most often, New York City with certain destruction. These have been repeatedly repelled by superheroes, somewhat human somewhat not, and the P.O.V. from which we the reader have always viewed these events has been as one of the superpeople at the heart of the battle, deeply enmeshed in the passionate immediacy of the short-term drama, nemeses, kidnappings, personal backstory, and who’s dead lately. Only rarely have we had works that gave us a longer perspective over time, reflecting personal change, evolving perspectives, how being constantly enmeshed in superbusiness makes a person develop and self-reflect, though notably the works that have done so have been among superhero comics’ shining stars (Dark Knight Returns, Red Son, Watchmen.)

Marvels instead offers a long-term and distanced P.O.V., that of a photographer who lives in New York City and, during his path from rookie to retirement, experiences in order the great, visible cataclysms that have repeatedly shaken Marvel’s Earth. His perspective gives historicity, sentiment, reflection and above all realism to Marvel, using it as alternate history rather than an action setting. The effect is powerful, beautiful and highly recommended for the way it weaves the richness of Marvel’s setting together with good writing to create a truly valuable work of literature. But it also reverses an interesting silencing which has been present in the back of Marvel, and superhero comics, since their inception: the silencing of the Public.

Very much like the women in early versions of Arthuriana, the Public in Marvel (and DC) has not been an agent in itself, but an object to motivate the hero. The Public exists to be rescued, protected, placated, evaded, sometimes feared. The Public has cheered P.O.V. heroes, hounded them, betrayed them, threatened them with pitchforks and torches, somehow being tricked over and over again into doubting the heros even after the last seventeen times they were exonerated. The Marvel Public specifically also persistently hates and fears the X-Men and other mutants despite being saved by them sixteen jillion times, and somehow hates and fears the other heros less even though many of them are aliens or science freaks or robots or other things just as weird as mutants. It is a tool of the author, manipulated by villains, oppressing misfits, causing tension, but virtually never is the reader asked to empathize with the Public. The object of empathy is the hero, or occasionally the villain, but the reader is never supposed to identify with or even think about the emotions of the screaming and yet simultaneously silenced mob. Marvels gives us, at last, the point of view of that mob, or at least one member of it, directing our self-identification and above all our empathy for the first time to something which has been hitherto faceless.

Very much like the women in early versions of Arthuriana, the Public in Marvel (and DC) has not been an agent in itself, but an object to motivate the hero. The Public exists to be rescued, protected, placated, evaded, sometimes feared. The Public has cheered P.O.V. heroes, hounded them, betrayed them, threatened them with pitchforks and torches, somehow being tricked over and over again into doubting the heros even after the last seventeen times they were exonerated. The Marvel Public specifically also persistently hates and fears the X-Men and other mutants despite being saved by them sixteen jillion times, and somehow hates and fears the other heros less even though many of them are aliens or science freaks or robots or other things just as weird as mutants. It is a tool of the author, manipulated by villains, oppressing misfits, causing tension, but virtually never is the reader asked to empathize with the Public. The object of empathy is the hero, or occasionally the villain, but the reader is never supposed to identify with or even think about the emotions of the screaming and yet simultaneously silenced mob. Marvels gives us, at last, the point of view of that mob, or at least one member of it, directing our self-identification and above all our empathy for the first time to something which has been hitherto faceless.

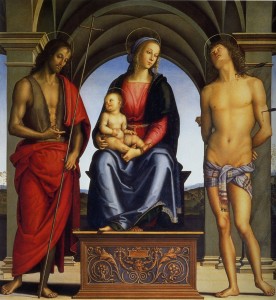

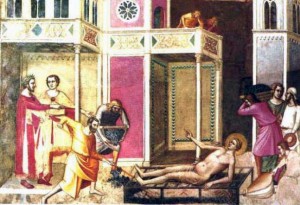

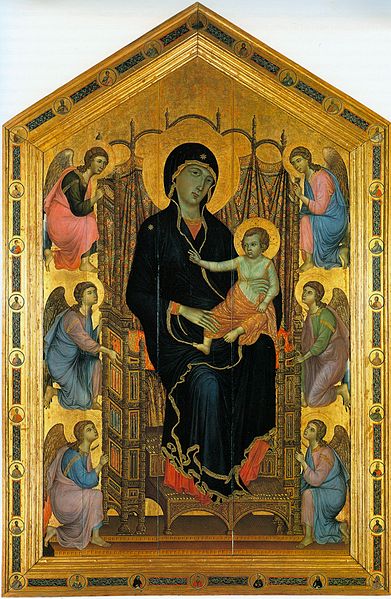

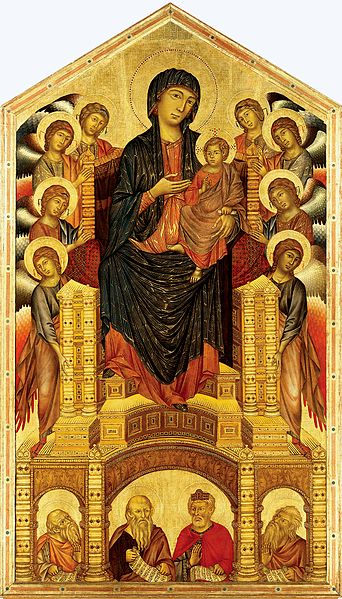

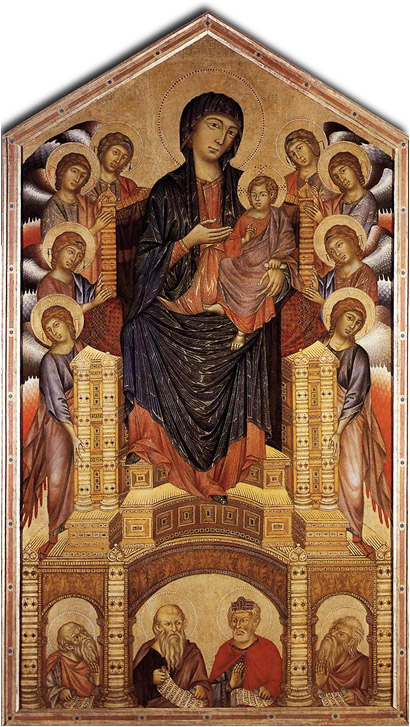

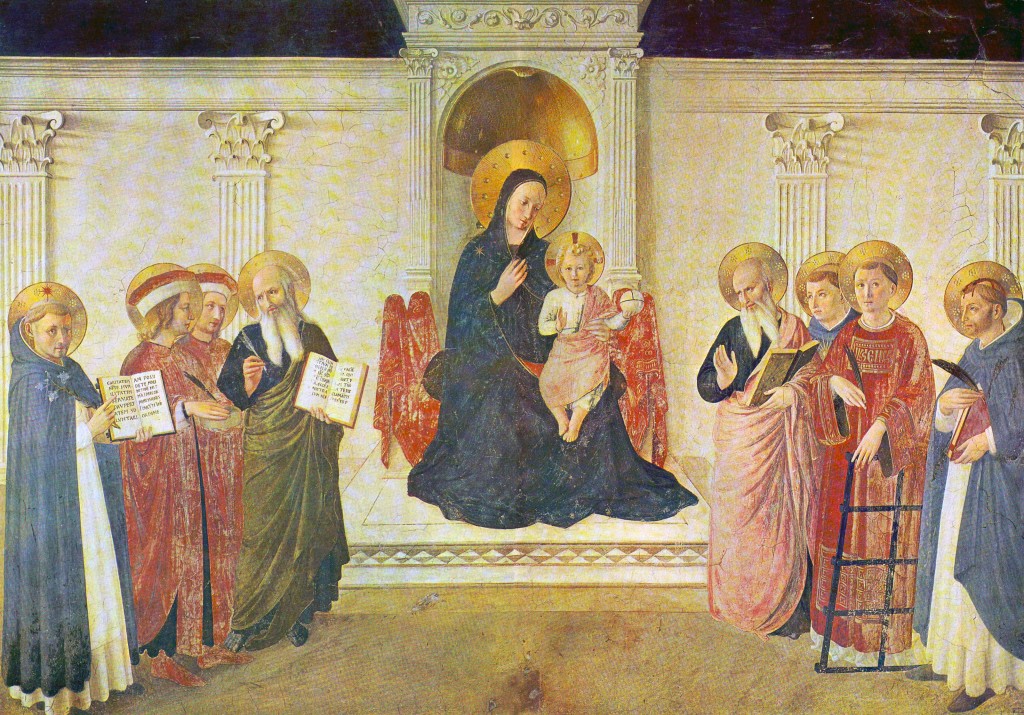

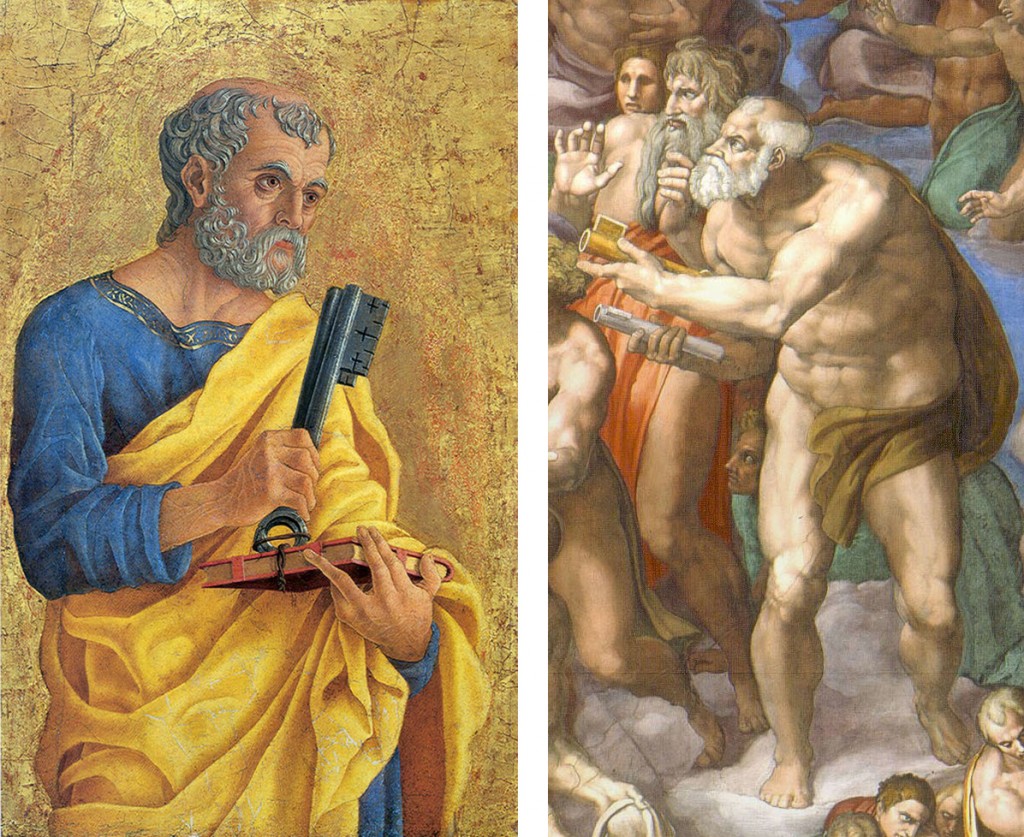

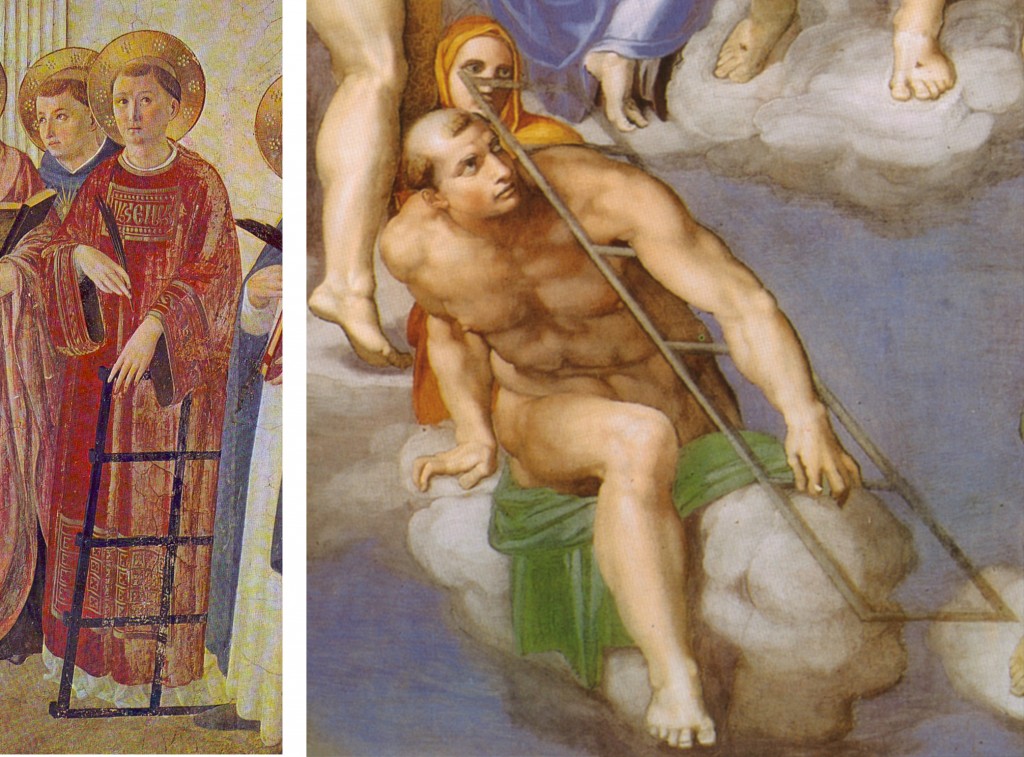

The effect is rather like a stroll through the Uffizi enjoying endless scenes of exciting saints surrounded by choruses of beautiful angels and then hitting the Botticelli room where each angel has a distinctive face and personality and you find yourself wondering what that angel is thinking when it watches Mary come to heaven to be crowned its queen, or sings music for young John the Baptist whose grisly end and subsequent heavenly ascension the angel already knows. Only when Botticelli invites you to see the angels as individuals do you realize that no earlier painting ever did. They had a failure of empathy. They were still beautiful, but here is a rich new direction for empathy which no earlier work has asked us to consider, and which opens up a huge arena we had ignored. Women in Arthuriana; the Public in Marvel; the angels that stand around in paintings of saints.

In just the same way, “The Litany of Earth” uses empathy and P.O.V. to open rich new arenas in one of our other well-known modern fictional settings. And the setting it uses has a fundamental and very problematic failure of empathy rooted deep in its foundations, so addressing that head-on opens a very potent door.

And since I can feel the urge to talk about Naoki Urasawa’s Pluto becoming harder to resist, I believe it is now time to nip that in the bud by moving on to the next stage of my plan.

Step Three: Ramble about Petrarch.

Step Three: Ramble about Petrarch.

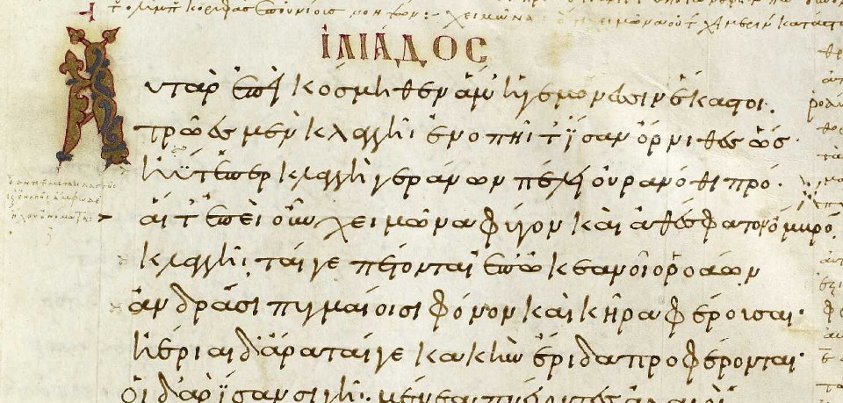

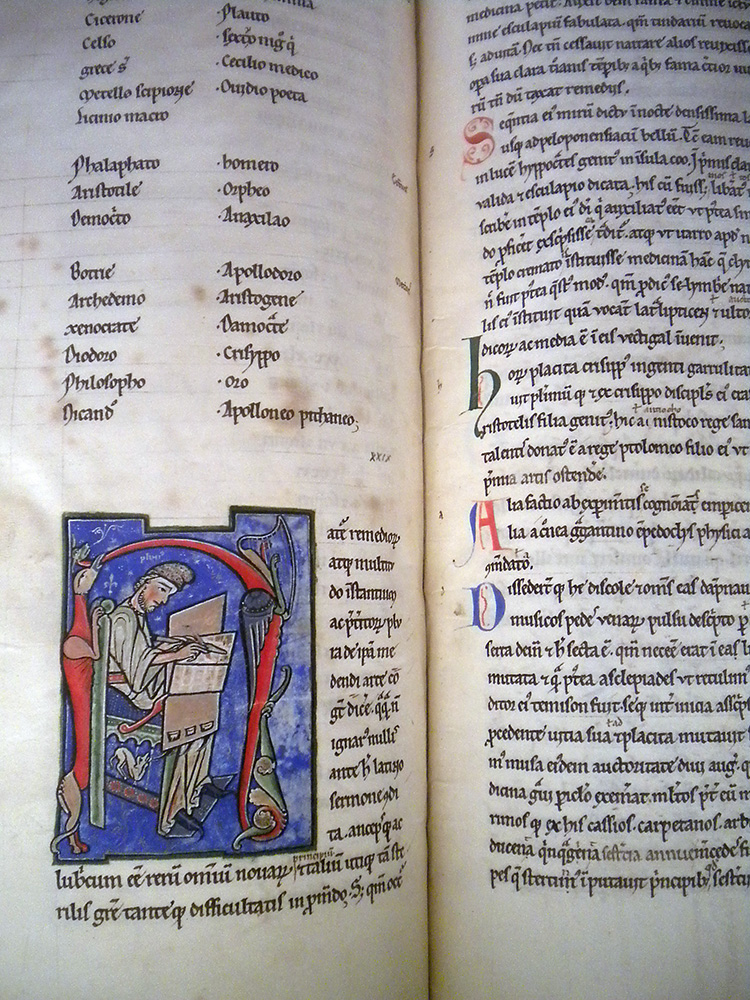

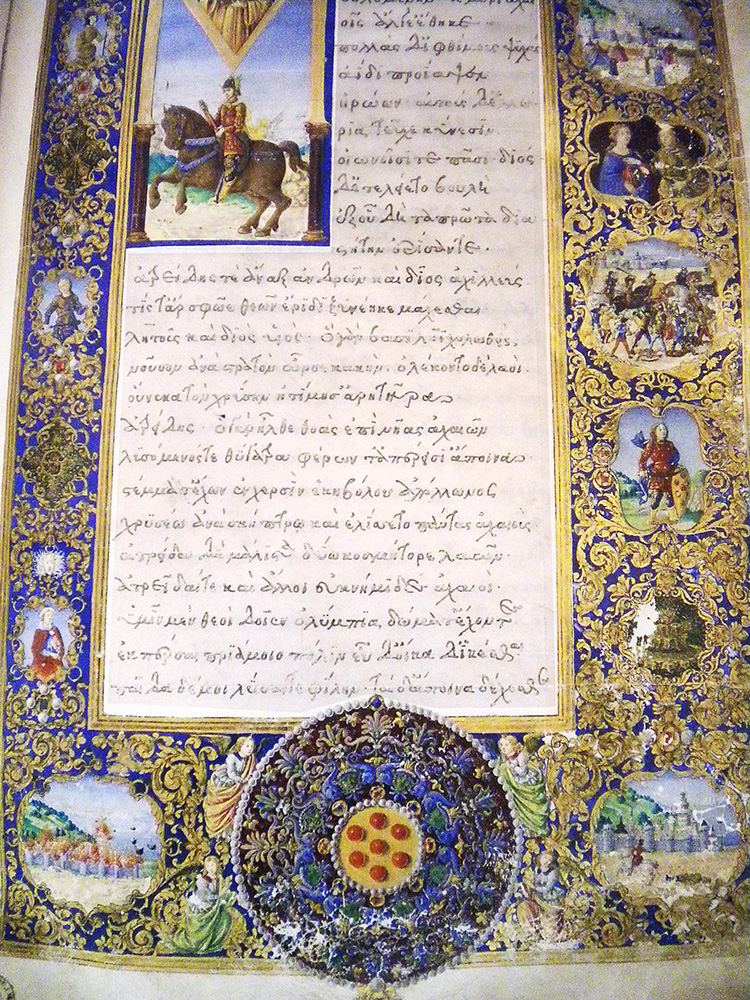

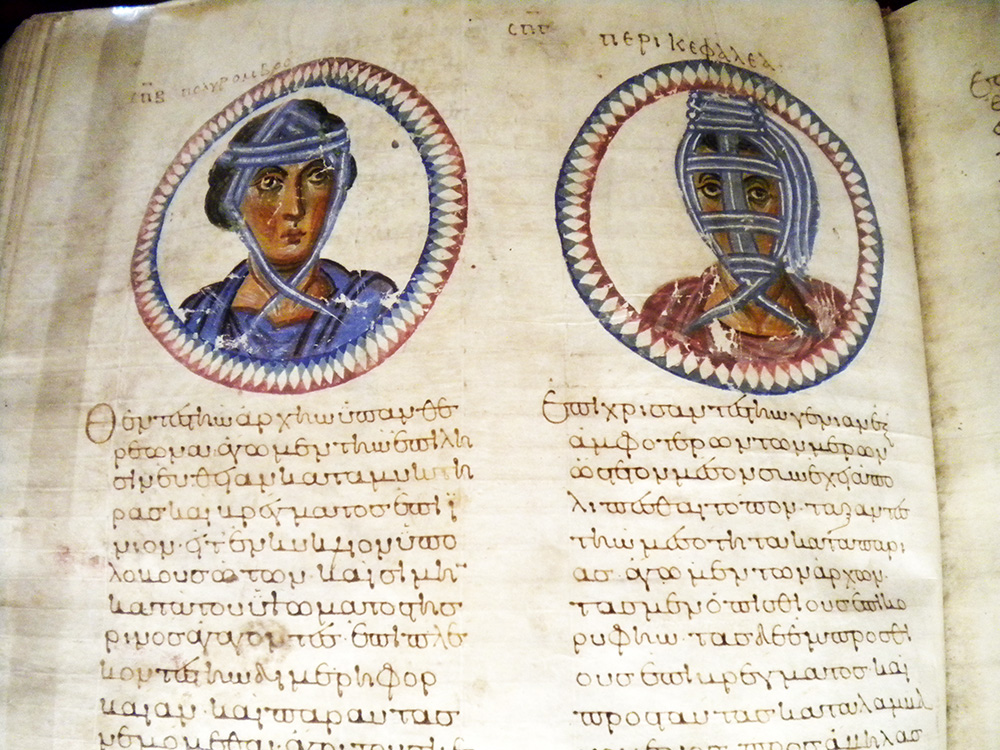

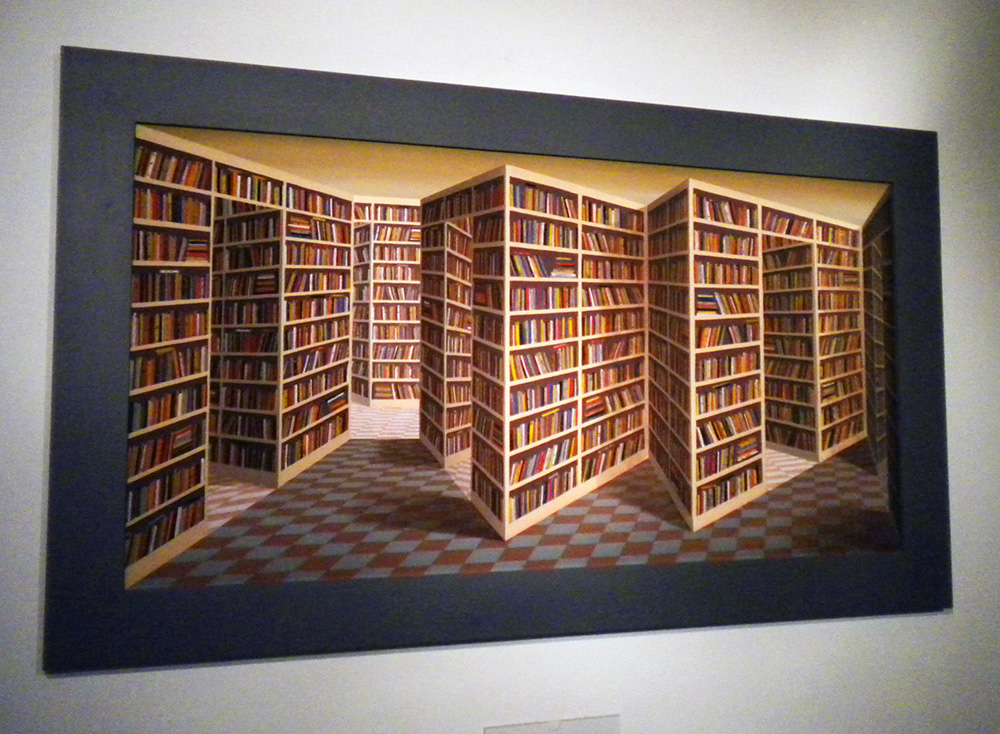

Picture Petrarch in his library, holding his Homer. He has just received it, and turns the stiff vellum pages slowly, his fingertips brushing the precious verses that he has dreamed of since his boyhood. The Iliad in his hands. His friends have always whispered to him of the genius that was Homer, his real friends, not the shortsighted fools he grew up with in Avignon, arrogant Frenchman and slavish Italians like his parents who followed the papacy and its trail of gold even when France snatched it away from Rome. His real friends are long-dead Romans: Cicero, Seneca, Caesar, men like him who love learning, love virtue, love literature, love Rome and Italy enough to fight and give their lives for it, love truth and excellence enough to write of it with passion and powerful words that sting the reader into wanting to become a better person.

Petrarch was born in exile. Not just the geographic exile of his family from their Florentine homeland, no, something deeper. An exile in time. This world has no one he can relate to, no one whose thoughts are shaped like his, who walks the Roman roads and feels the flowing currents of the Empire, whose understanding of the world connects from Egypt up to Britain without being blinded by ephemeral borders, who can name the Muses and knows how truly rich it is to taste the arts of all nine, and how truly poor one is without. Antiquity was his native time, he knows it, but antiquity was cut off too early–he was born too late. His friends are dead, but their voices live, a few, in chunks, in the books in distant libraries which he has spent his life and fortune gathering. His library. Each volume a new shard of a missing friend, those few, battered whispers of ancient voices which survived the Medieval cataclysm that consumed so much. And now, after hearing so many of his friends speak of Homer, call him the Prince of Poets, the climax of all art and literature, divine epic, the centerpiece of all the ancient world, he has it in his hands. It survived. Homer. In Greek. And he can’t read it. Not a word of it. Greek is gone. No one can read it anymore, no one. Homer. He has it in his hand, but he can’t read it, and for all he knows no one ever will again.

Petrarch was born in exile. Not just the geographic exile of his family from their Florentine homeland, no, something deeper. An exile in time. This world has no one he can relate to, no one whose thoughts are shaped like his, who walks the Roman roads and feels the flowing currents of the Empire, whose understanding of the world connects from Egypt up to Britain without being blinded by ephemeral borders, who can name the Muses and knows how truly rich it is to taste the arts of all nine, and how truly poor one is without. Antiquity was his native time, he knows it, but antiquity was cut off too early–he was born too late. His friends are dead, but their voices live, a few, in chunks, in the books in distant libraries which he has spent his life and fortune gathering. His library. Each volume a new shard of a missing friend, those few, battered whispers of ancient voices which survived the Medieval cataclysm that consumed so much. And now, after hearing so many of his friends speak of Homer, call him the Prince of Poets, the climax of all art and literature, divine epic, the centerpiece of all the ancient world, he has it in his hands. It survived. Homer. In Greek. And he can’t read it. Not a word of it. Greek is gone. No one can read it anymore, no one. Homer. He has it in his hand, but he can’t read it, and for all he knows no one ever will again.

This historical moment, Petrarch with his Homer, is one of the most poignant I have ever met in my scholarship. A portrait of discontinuity. The pain when the chain of cultural transmission, of old hands grasping young, that should connect past, present and future is cut off. The cataclysm doesn’t have to be complete to be enough to disrupt, to silence, to jumble, to leave too little, Greek without Homer, Homer without Greek. Petrarch is a Roman. They all are, he and his Renaissance Italians, they have the blood of the Romans, the lands of the Romans, the ruins of the Romans, but not enough for Petrarch to ever really have the life he might have had if he’d been born in the generation after Cicero, and with his Homer in his hands he knows it.

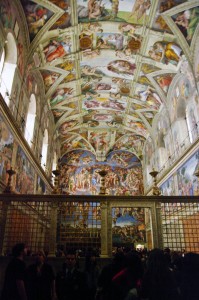

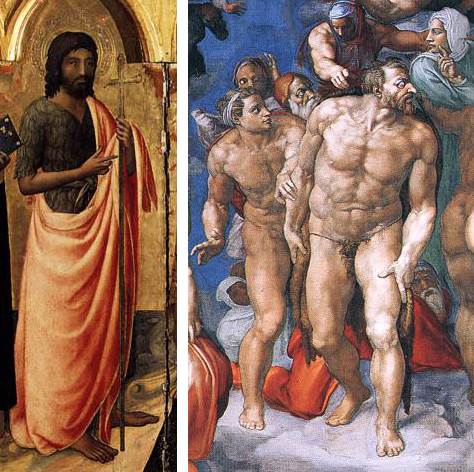

Petrarch did his best. He spent his life collecting the books of the ancients, trying to reassemble the Library of Alexandria, the pinnacle, he knew, of the culture and education which had made the Romans who had made his world. He found many shards, eventually enough that it took more than ten mules to carry his library when he journeyed from city to city. He journeyed much, working everywhere with voice and pen to convince others to share his passion for antiquity, to read the ancients that could be read, Cicero, Seneca, to learn to think as they did and to try to push this world to be Roman again, which for him meant peaceful, broad-reaching, stable, cultured and strong. People listened, and we have the libraries and cathedrals and Michelangelos they made in answer. And Petrarch never gave up on Homer either, but searched the far corners of the Earth for someone with a hint of Greek and eventually, late in life, did find someone to make a jumbled, fragmentary translation, nothing close to what a second-year-Greek student could produce today let alone a fluid translation, but a taste. By late in life he had his New Library of Alexandria, and real hope that it might rear new Romans.

Petrarch did his best. He spent his life collecting the books of the ancients, trying to reassemble the Library of Alexandria, the pinnacle, he knew, of the culture and education which had made the Romans who had made his world. He found many shards, eventually enough that it took more than ten mules to carry his library when he journeyed from city to city. He journeyed much, working everywhere with voice and pen to convince others to share his passion for antiquity, to read the ancients that could be read, Cicero, Seneca, to learn to think as they did and to try to push this world to be Roman again, which for him meant peaceful, broad-reaching, stable, cultured and strong. People listened, and we have the libraries and cathedrals and Michelangelos they made in answer. And Petrarch never gave up on Homer either, but searched the far corners of the Earth for someone with a hint of Greek and eventually, late in life, did find someone to make a jumbled, fragmentary translation, nothing close to what a second-year-Greek student could produce today let alone a fluid translation, but a taste. By late in life he had his New Library of Alexandria, and real hope that it might rear new Romans.

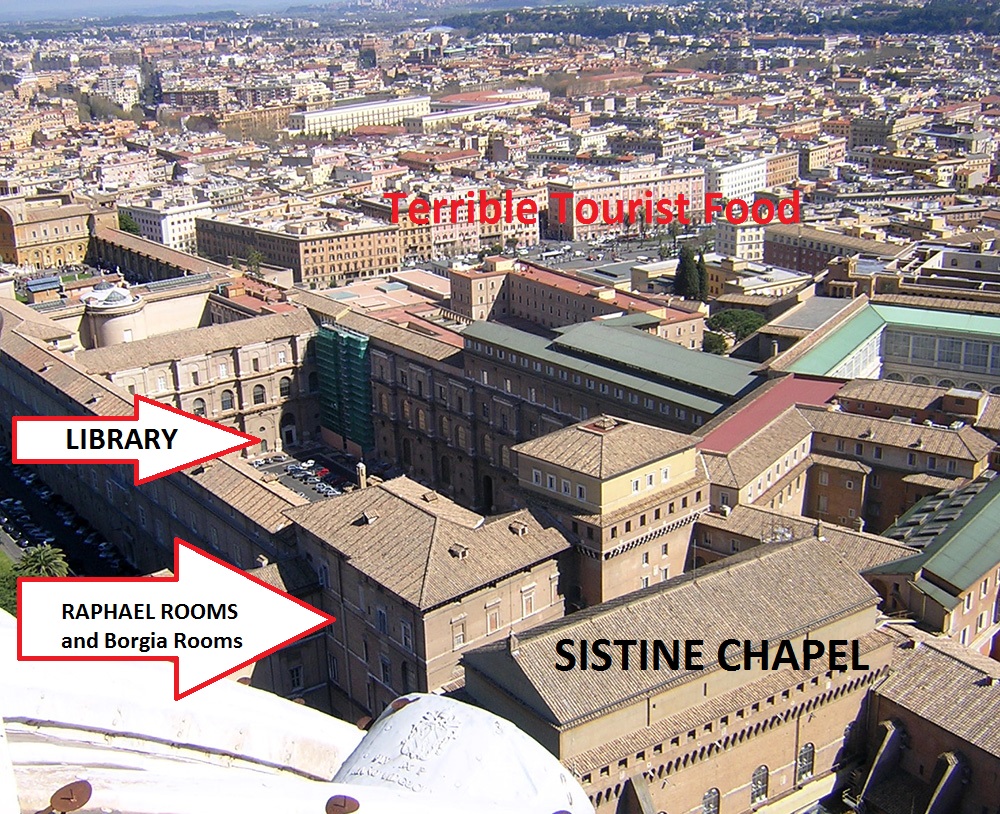

Petrarch wanted to give the library to Florence, to help his homeland make itself the new Rome, but Florence was too caught up with its own faction fighting for anyone to stably take it. Venice was the taker in the end, and he hoped his library would make the great port city like the Alexandria of old, the hub where all books came, and multiplied, and spread. Venice put Petrarch’s library in a humid warehouse and let it rot. We lost it. We lost it again. We lost it the first time because of Vandals and corrupt emperors and economic transformation and plague and all the other factors that conspired to make the Roman Empire decline and fall, but we lost it the second time because Venice is humid and no one cared enough to devote space and expense to a library, even the famous collection of the famous Petrarch. Such a tiny cataclysm, but enough to make discontinuity again. We have learned better since. Petrarch had followers who formed new libraries, Poggio, Niccolo, they repeated Petrarch’s effort, finding books. Eventually princes and governments realized there was power in knowledge. Venice built the Marciana library right at the main landing, so when foreigners arrive in St. Mark’s square they are surrounded by the three facets of power, State in the Doge’s Palace, Church in the Basilica, and Knowledge in the Library. And now we have our Penguin Classics. But we don’t have Petrarch’s library, and we know he had things that were rare, originals, transcriptions of things later lost. There are ancients who made it as far as Petrarch, all the way to the late 1300s, through Vandals, Mongols and the Black Death, before we lost them to one short-sighted disaster. Discontinuity. We have Homer. We don’t know what Petrarch had that we don’t.

This was one of two historical vignettes that came vividly before my mind while I was reading “The Litany of Earth.” The second is…

Step Four: Ramble about Diderot. Dear, dear Diderot…

I must be very careful here. Even though my focus is Renaissance and my native habitat F&SF, Denis Diderot remains my favorite author. Period. My favorite in the history of words. So it is very easy for me to linger too long . But I invoke him today for a very specific reason and shall confine myself strictly to one circumscribed subtopic, however hard the copy of Rameau’s Nephew on my desk stares back.

I must be very careful here. Even though my focus is Renaissance and my native habitat F&SF, Denis Diderot remains my favorite author. Period. My favorite in the history of words. So it is very easy for me to linger too long . But I invoke him today for a very specific reason and shall confine myself strictly to one circumscribed subtopic, however hard the copy of Rameau’s Nephew on my desk stares back.

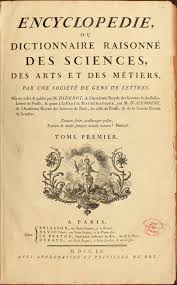

Three quarters of the way through my survey course on the history of Western thought, I start a lecture by declaring that the Enlightenment Encyclopedia project was the single noblest undertaking in the history of human civilization. I say it because of the defiant, “bring it on!” glances I instantly get from the students, who switch at once from passive listening to critical judgment as they arm themselves with the noblest human undertakings they can think of, and gear up to see if I can follow through on my bold boast. I want that. I want their minds to be full of the Moon Landing, and the Spartans at Thermopylae, and Gandhi, and the US Declaration of Independence, and Mother Teresa, and the Polynesians who braved the infinite Pacific in their tiny log boats; I want it all in their minds’ eyes as I begin.

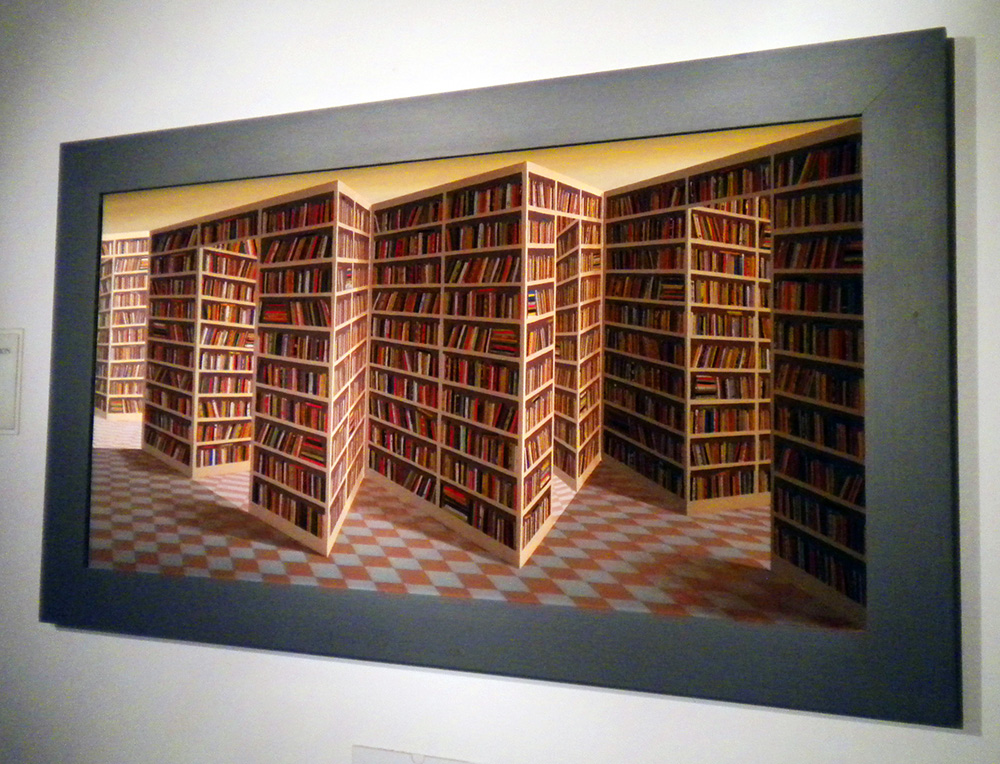

The Encyclopédie was the life’s work of a century on fire. The newborn concept Progress had taken flight, convincing France and Europe that the human species have the power to change the world instead of just enduring it, that we can fight back against disease, and cold, and mountain crags, and famine cycles, and time, and make each generation’s experience on this Earth a little better. The lion has its claws and strength, the serpent fangs and stealth, the great whales the force of the leviathan, but humans have Reason, and empiricism, and language to let us collaborate, discuss, examine, challenge, and form communities of scientists and thinkers who, like the honeybee, will gather the best fruits of nature and, processing them with our own inborn gifts, produce something good and sweet and useful for the world. The tone here is Francis Bacon’s, but Voltaire popularized it, and by now the fresh passion for collaboration and improvement of the human world had already birthed Descartes’ mathematics, Newton’s optics, Locke’s inalienable rights, calculus, and the Latitudinarian movements toward rational religion which seemed they might finally soothe away the wars that lingered from the Reformation. Everything could be improved if keen minds applied reason to it, from treatments for smallpox which could be preventative instead of palliative, to Europe’s law codes which were not rational constructions but mongrel accumulations of tradition and centuries-old legislation passed during half-forgotten crises and old power struggles whose purpose died with the clans and dynasties that made them but which still had the power to condemn a feeling, thinking person to torture and death.

The Encyclopédie was the life’s work of a century on fire. The newborn concept Progress had taken flight, convincing France and Europe that the human species have the power to change the world instead of just enduring it, that we can fight back against disease, and cold, and mountain crags, and famine cycles, and time, and make each generation’s experience on this Earth a little better. The lion has its claws and strength, the serpent fangs and stealth, the great whales the force of the leviathan, but humans have Reason, and empiricism, and language to let us collaborate, discuss, examine, challenge, and form communities of scientists and thinkers who, like the honeybee, will gather the best fruits of nature and, processing them with our own inborn gifts, produce something good and sweet and useful for the world. The tone here is Francis Bacon’s, but Voltaire popularized it, and by now the fresh passion for collaboration and improvement of the human world had already birthed Descartes’ mathematics, Newton’s optics, Locke’s inalienable rights, calculus, and the Latitudinarian movements toward rational religion which seemed they might finally soothe away the wars that lingered from the Reformation. Everything could be improved if keen minds applied reason to it, from treatments for smallpox which could be preventative instead of palliative, to Europe’s law codes which were not rational constructions but mongrel accumulations of tradition and centuries-old legislation passed during half-forgotten crises and old power struggles whose purpose died with the clans and dynasties that made them but which still had the power to condemn a feeling, thinking person to torture and death.

The Encyclopédie had many purposes. Perhaps the least ambitious was to turn every citizen of Earth into a honeybee. Plato had said that only a tiny sliver of human souls were truly guided by reason–able to become Philosopher Kings–while the vast majority were inexorably dominated by base appetites, the daily dose of food and rest and lust, or by the wild but selfish passions of ambition and pride. For two millennia all had agreed, and even when the Renaissance boasted that human souls could rival angels in dignity and glory through the light of learning and the power of Reason, they meant the souls of a tiny, literate elite. But in 1689 John Locke had argued that humans are born blank slates, and nurture rather than an innate disposition of the soul separated young Newton from his father’s stable boy. The Encyclopédie set out to enable universal education, to collect basic knowledge of all subjects in a form accessible to every literate person, and to their illiterate friends who crowded around to hear new chapters read aloud in the heady excitement of its first release. With such an education, everyone could be a honeybee of Progress, and exponential acceleration in discovery and social improvement would birth a better world. So overwhelming was public demand that Europe ran out of paper, of printer’s ink, even ran out of the types of metal needed to make printing presses, so many new print shops appeared to plagiarize and print and sell more and more copies of the book which promised such a future (See F. A. Kafker, “The Recruitment of the Encyclopedists”).

The Encyclopédie had many purposes. Perhaps the least ambitious was to turn every citizen of Earth into a honeybee. Plato had said that only a tiny sliver of human souls were truly guided by reason–able to become Philosopher Kings–while the vast majority were inexorably dominated by base appetites, the daily dose of food and rest and lust, or by the wild but selfish passions of ambition and pride. For two millennia all had agreed, and even when the Renaissance boasted that human souls could rival angels in dignity and glory through the light of learning and the power of Reason, they meant the souls of a tiny, literate elite. But in 1689 John Locke had argued that humans are born blank slates, and nurture rather than an innate disposition of the soul separated young Newton from his father’s stable boy. The Encyclopédie set out to enable universal education, to collect basic knowledge of all subjects in a form accessible to every literate person, and to their illiterate friends who crowded around to hear new chapters read aloud in the heady excitement of its first release. With such an education, everyone could be a honeybee of Progress, and exponential acceleration in discovery and social improvement would birth a better world. So overwhelming was public demand that Europe ran out of paper, of printer’s ink, even ran out of the types of metal needed to make printing presses, so many new print shops appeared to plagiarize and print and sell more and more copies of the book which promised such a future (See F. A. Kafker, “The Recruitment of the Encyclopedists”).

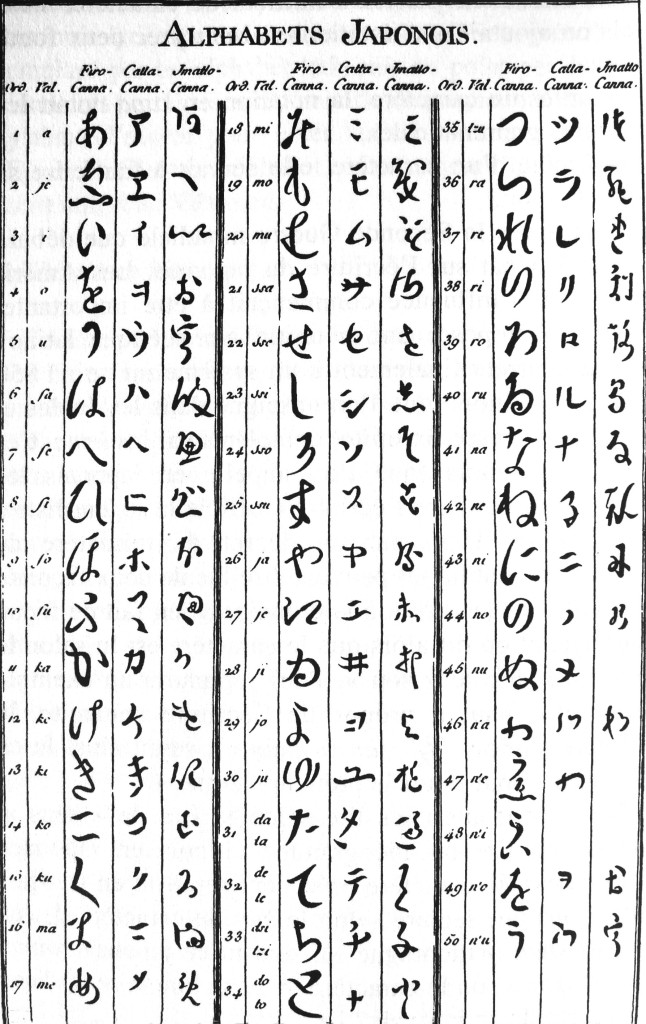

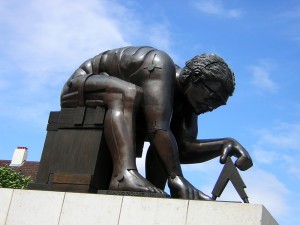

Yet Diderot and his compatriots had another goal which shows itself in the structure of the Encyclopédie as well as in its bold opening essay. The second half of the 17 volume series is devoted to visual material, a series of beautiful and immensely complicated technical plates which illustrate technology and science. How to fire china dishes, smelt ore, weave rope, irrigate fields, construct ships, calculate distance, catalog fossils and decorate carriages, all are illustrated in loving detail, with diagrams of every tool and its use, every factory and its layout, every human body at work in some complex motion necessary to turn cotton into cloth or rag into precious paper. With this half of the Encyclopédie it is possible to teach one’s self every technological achievement of the age. The first half was intended to provide the same for thought. With its essays it should be possible to understand from their roots the philosophies, ethical systems, law codes, customs, religions, great thinkers of the past and present, all aspects of life and the history of humankind’s evolving mental world. It is a snapshot. A time capsule. With this–Diderot smiles thinking it–with this, if a new Dark Age fell upon humanity and but a single copy of the Encyclopédie survived, it would be possible to reconstruct all human progress. With this, the great steps forward, the hard-earned produce of so many lives, the Spartans at Thermopylae, the Polynesian log boats, will be safe forever. We can’t fall back into the dark again. With this, human achievement is immortal. Yes, Petrarch, it even details how to read, and print, and translate Greek.

Let’s linger on that thought a moment. A beautiful, unifying, optimistic, safe, human moment, warm, like when I first heard that, yes, eventually Petrarch did get to read a sliver of his Homer. Because I’m not going to keep talking about dear Diderot today, much as I would like to.

In 2012/13 we lost 170,000 volumes from the Egyptian Scientific Institute in Cairo to the revolution, 20,000 unique manuscripts in Timbuktu library to a militia fire, and we have barely begun to count the masses of original scientific material burned during a corrupt botched cost-saving effort to reduce the size of the Libraries of Fisheries and Oceans of Canada. More than half of the entries on Wikipedia’s list of destroyed libraries were destroyed after the printing of the Encyclopédie, and the libraries on the list are only a miniscule fraction of the texts lost to disasters, natural and manmade. It doesn’t even list Petrarch’s library, let alone the unique contents of the personal libraries and works that accumulate in every house now that we’re all honeybees. Diderot tried so hard to make it all immortal. He tried so hard he used up all the ink and paper in the world. Yet if my numbers for printing history are right, in the past half century we have destroyed more written material than had been produced in the cumulative history of the Earth up until Diderot’s day. And that does not count World Wars. We’re getting better. On February 14th 2014 a fire at the British National Archives threatening thousands of documents, many centuries old, was successfully quenched with no damage to the collection, thanks substantially to advances in our understandings of fluids and pressure made in the 17th and 18th centuries and neatly explained by the Encyclopédie. That much is indeed immortal (thank you, Diderot!) but much is so very far from everything. It’s still so easy to make mistakes.

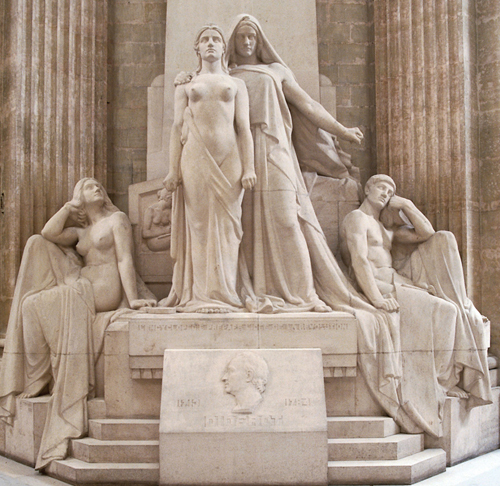

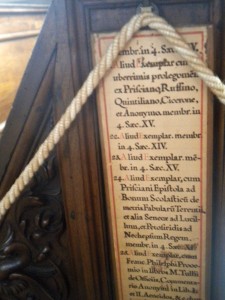

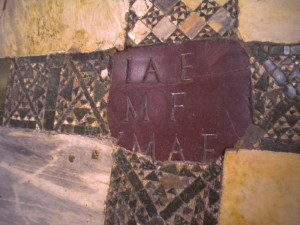

One of the most powerful mistakes, for me, is this cenotaph monument of Diderot, in the Pantheon in Paris, celebrating his contributions and how the Encyclopedia and enlightenment enabled so much of the liberty and rights and change that defines our era. Voltaire’s tomb was moved to the Pantheon, Rousseau’s too, but for Diderot there is only this empty cenotaph. I went on a little pilgrimage once to visit Diderot in the out-of-the-way Church of Saint-Roch, where he was buried. There is no tomb to visit. During the French Revolution, Saint-Roch was attacked and mostly destroyed by revolutionaries (carrying banners with Encyclopedist slogans on them!) who, in their zeal to torch the old regime, forgot that their own Diderot was among the Catholic trappings they could only see as symbols of oppression. Once rage and zeal had died down Paris and all France much lamented the mistake, and many others, too late.

One of the most powerful mistakes, for me, is this cenotaph monument of Diderot, in the Pantheon in Paris, celebrating his contributions and how the Encyclopedia and enlightenment enabled so much of the liberty and rights and change that defines our era. Voltaire’s tomb was moved to the Pantheon, Rousseau’s too, but for Diderot there is only this empty cenotaph. I went on a little pilgrimage once to visit Diderot in the out-of-the-way Church of Saint-Roch, where he was buried. There is no tomb to visit. During the French Revolution, Saint-Roch was attacked and mostly destroyed by revolutionaries (carrying banners with Encyclopedist slogans on them!) who, in their zeal to torch the old regime, forgot that their own Diderot was among the Catholic trappings they could only see as symbols of oppression. Once rage and zeal had died down Paris and all France much lamented the mistake, and many others, too late.

Did I mention we very nearly lost Diderot’s work too? A far more frightening loss than just his body. Diderot didn’t include himself, his own precious original intellectual contributions, in his Encyclopédie. He knew he couldn’t. He was an atheist, you see. A real one, not one of these people we suspect like Hobbes and Machiavelli, but an overt atheist who wrote powerful, deeply speculative books trying to hash out the first moral system without divinity in it, fledgling works of an intellectual tradition which was just then being born, since even a few decades earlier no one had dared set pen to paper, for fear of social exile and ready fire and steel of Church and law. But Diderot didn’t publish his own works, not even anonymously. He self-censored. He was the figurehead of the Encyclopédie. An atheist was too frightening back then, too strange, too other. If people had known an atheist was part of it, the project would have been dead in the water. Diderot left instructions for future generations to print his works someday, if the manuscripts survived, but gambling with his own legacy was a price he was willing to pay to immortalize everyone else’s. The surviving manuscript of Rameau’s Nephew in Diderot’s own hand turned up by chance at a used bookshop 1823, one chance street fire away from silence.

Step Five: Urge you to read “The Litany of Earth” again, last chance before I get out my highlighter.

Here you get points if you read it before getting this far. It’s free on Tor.com, but you really liked it you can also buy the ebook for a dollar, and give money to Ruthanna and to Tor, and tell them you like excellent original fiction that does brave things with race and historicity.

Step Six: Talk about “The Litany of Earth” directly.

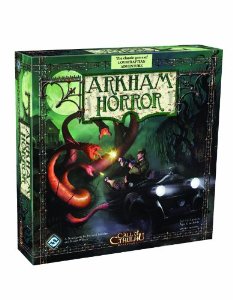

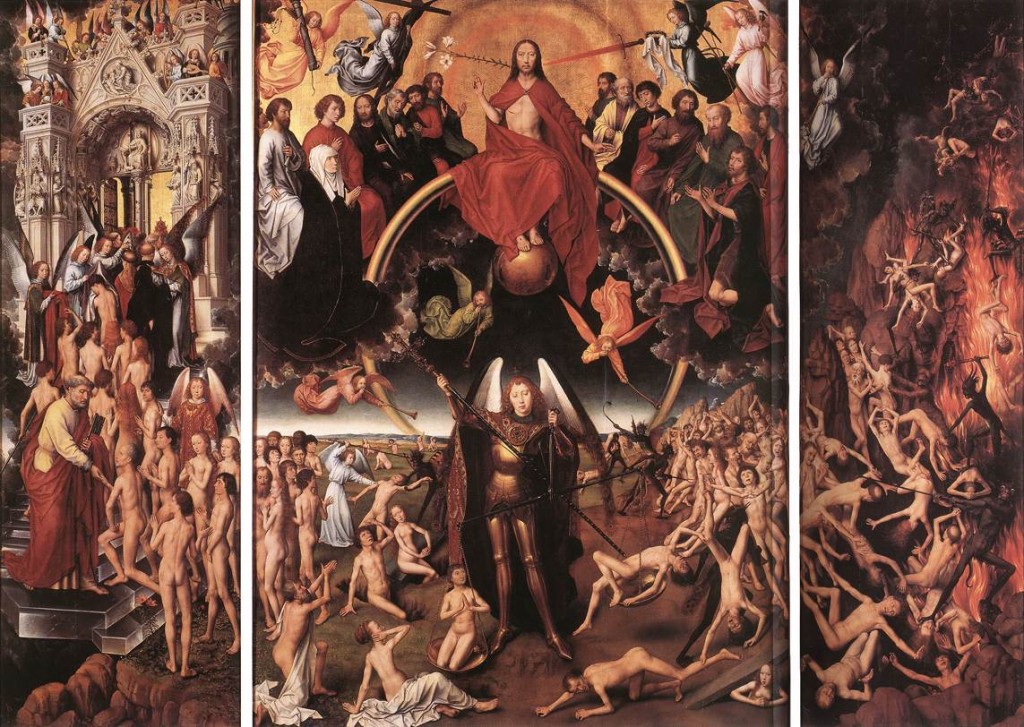

This is a Cthulhu Mythos story which is in no way horror. The richly-designed populated metaphysics and macrohistorical narrative of Lovecraft’s universe is here, but as a tool for reflection on society and self, with a narrative that bears no resemblance in to the classic tense and chilling horror short stories I (for some reason) enjoy as bedtime reading. Ruthanna Emrys uses Lovecraft’s world to comment on Lovecraft’s writing and the deeply ingrained sexism and especially racism that saturates it, repurposing that into a tool to make us think more about the effects of silencing and othering which Lovecraft used his skill and craftsmanship to lure us into participating in. But the message and questions are universal enough that the target audience is not Lovecraft readers or horror readers but any reader who has even a vague distant awareness that the Lovecraft Mythos is a thing, as one has a vague distant awareness of Celtic or Navajo mythology even if one doesn’t study them. If there is any horror in this story, it is the familiar reality that the things we make and do and are are perishable, that human action often worsens that, and that at the end of all our aeons and equations we face entropy. But rather than presuming (as Lovecraft and much horror does) that facing that will lead to mad cackling and gibberish, the story presents the real things we do to try to face that: spirituality, cultural identity, and the effort to preserve the past and transmit it to the future. It turns a setting which was created a vehicle for horror into a vehicle for social commentary and historical reflection.

I suppose I should directly address Lovecraft’s failures of empathy, for those less familiar with his work, or who have met it mainly through its fun, recent iterations in board games and reuses which strive to leave behind the baggage. Racism, sexism, classism and other uncomfortable attitudes are not unexpected in an author who lived from 1890 to 1937. We encounter unpalatable depictions of people of color, and equally unpalatable valorizations of entrenched elites, in most literature of the period, from M. R. James to the original Sherlock Holmes. In Lovecraft’s case, the challenge for those who want to continue to work with his universe is that many of the racist and classist elements are worked deeply into the fabric of his worldbuilding. Many of his frightening inhuman races are clearly used to explore his fear of racial minorities, while the keys to battling evil are reserved for elites, like the affluent, white, male scholars who control his libraries, and the Great Race which controls the greatest library.

While many attempts to rehabilitate and use Lovecraft’s world do so by excising these elements, or minimizing them, or balancing them out by letting you play ethnically diverse characters in a Lovecraft game, this story instead uses those very elements as weapons against the kinds of attitudes which birthed them. If the scary fish-people represent a demonized racial “other” then let them remain exactly that, and show them suffering what targeted minorities have suffered in historical reality. By reversing the point of view and placing the reader within the perspective of the “other”, the original failure of empathy is transformed into a triumph of empathy. Now we are in the place of a woman for whom Lovecraft’s spooky cult rituals are her Passover or Easter, the mysterious symbols her alphabet, “Iä, Cthulhu . . . ” is the comforting prayer she thinks to herself when terrified, and a Necronomicon on Charlie’s shelf is Petrarch’s Homer.

And we aren’t asked to empathize with only one group. We empathize with those deprived of education, in the form of Aphra’s brother Caleb, taking on the classist negative depictions of “degenerate” white rural families common in Lovecraft’s work. With the plight of the Jews and other groups targeted in Germany, invoked by Specter’s discussion of his aunt. With those facing physical and medical challenges, invoked in the powerful opening lines where Aphra describes the pleasure she finds in facing the daily difficulty of walking uphill while she slowly heals. And with women, rarely granted any remotely coequal agency in literature of Lovecraft’s era. Not only is this story a powerful triumph of empathy, but after reading it, whenever we reread original Lovecraft, or anything set in his world, the memory of Aphra Marsh and her tender prayer will forever change the meaning of “Iä, iä, Cthulhu thtagn…” The triumph of empathy diffuses past the boundaries of this story, to enrich our future reading.

Another striking facet is that this is a story about legacy, continuity and deep history that manages to address those questions using only very recent history. Usually stories that want to talk about the deep past use material from periods we associate with the deep past: medieval, Roman Empire, Renaissance, Inuits, Minoans, anything we associate with dusty manuscripts and archaeology and anthropology and old culture. Even I in this entry, when trying to evoke the themes and feelings of this story, went back centuries and consequently had to spend a lot of time explaining to the reader the history I’m talking about (what’s Petrarch’s Homer, what’s up with Diderot, etc.) before I could get to what I wanted to do with it. This story instead uses contemporary history, events so recent and familiar that we all know it already, and have seen its direct effects in those around us and ourselves, or have tried to not see said effects. As a result, the story doesn’t have the baggage of having to explain its history. Instead of needing footnotes and exposition, it touches us directly and personally with our own history and makes us directly face the fact that we too are part of the link of transmission attempting to connect past to future, and our failures can still heal or harm that just as much as Visigoths, the Black Death or the Encyclopédie. The use of modern history makes it impossible for us to distance ourselves, greatly enhancing its power.

I have already discussed, in my own roundabout way using Diderot and Petrarch and Marvel comics, many of the key themes which make this story so powerful: othering, empathy, reversal of point of view, legacy, silencing, translation and transmission, and discontinuity, how easy it is for the powerful engine of society to make mistakes that cut the precious thread. The power with which this story is able to present that theme demonstrates perfectly, for me, the potency of genre fiction as a tool, not for escapism or entertainment, but for depicting reality and history. The tragic discontinuities created by World War II, the destruction of life, education and cultural inheritance generated not only by the most gruesome facets of the war but also by great mistakes like the treatment of Japanese Americans, are difficult to communicate in full with such accurate but emotionless descriptive phrases as, “people were rounded up and held in prison camps.” Attempts to communicate the genuine human impact of such an event easily fall so short. We try hard, but often fail. As a teacher, I remember well the flurry of discussion which surrounded some High School history textbooks which, in their efforts to do justice to the often-silenced story of interned Japanese Americans, had a longer section about that than it did about the rest of the war. Opponents of political correctness used it as a talking point to rail against liberalism gone too far, while apologists focused on the harm done by silencing the events. Yet for me, the centerpiece was the fact that textbooks had to devote that much space to attempting to get the  issue across and still largely failed to communicate the event in a way that touched students. “The Litany of Earth” communicates the same event very potently, using the tool of genre to make something most readers might see as only affecting “others” feel universal. The large-scale horror of Lovecraft’s universe revolves around the inevitability that human achievement, and in the end all life, will fading into nothing. The Yith and their library are the only hope for a legacy, one bought at the terrible price of what they do to those whose bodies they commandeer. By creating a parallel between the fragility of all human achievement, preserved only by the Yith, and Aphra’s barely-literate brother Caleb writing of his doomed search for the family library which contained the history and legacy he and Aphra so desperately miss, the fantasy setting puts all readers in Aphra’s place, and the place of those interned, creating universal empathy which no textbook chapter could achieve; neither, in my opinion, could a non-fantasy short story, at least not with such deeply-cutting efficiency. After reading this story, not only the events of Japanese American internment but many parallel situations feel more personally important, and one feels a new sense of personal investment in such issues as the fate of the Iraqi Jewish Archive. This stoking of emotion and investment is a powerful and lingering achievement.

issue across and still largely failed to communicate the event in a way that touched students. “The Litany of Earth” communicates the same event very potently, using the tool of genre to make something most readers might see as only affecting “others” feel universal. The large-scale horror of Lovecraft’s universe revolves around the inevitability that human achievement, and in the end all life, will fading into nothing. The Yith and their library are the only hope for a legacy, one bought at the terrible price of what they do to those whose bodies they commandeer. By creating a parallel between the fragility of all human achievement, preserved only by the Yith, and Aphra’s barely-literate brother Caleb writing of his doomed search for the family library which contained the history and legacy he and Aphra so desperately miss, the fantasy setting puts all readers in Aphra’s place, and the place of those interned, creating universal empathy which no textbook chapter could achieve; neither, in my opinion, could a non-fantasy short story, at least not with such deeply-cutting efficiency. After reading this story, not only the events of Japanese American internment but many parallel situations feel more personally important, and one feels a new sense of personal investment in such issues as the fate of the Iraqi Jewish Archive. This stoking of emotion and investment is a powerful and lingering achievement.

Structurally, the story interweaves experiences from different points in Aphra’s present–where she encounters Specter–with her past arriving in the city and encountering Charlie and his interest in her lost culture and languages. The choice to depict the present scenes in past tense and the flashbacks in present tense might seem counterintuitive, but I found it a powerful and effective choice. Past tense reads as “normal” in prose, so much so that we accept it as an uncomplicated way to depict the main moment of a narrative. In contrast, especially when we have just come from a past tense section, the present tense feels extra-vivid, raw, invasive. It feels like a very certain type of memory, the kind so vivid that, when something reminds us of them, they jump to the forefront of our minds and blot out the here and now with the tense, unquenchable emotions of a very potent then. Trauma makes memories do this, but it is not the traumatic memories of camp life that we experience this way. Instead it is the vividness of tender moments of cultural experience: seeing precious books in Charlie’s study, sharing his drying river, warm things. The transitions to vivid present tense make the reader think about memory and trauma without having to show traumatic events, while simultaneously highlighting how, in such a situation of discontinuity and cultural deprivation, the experiences which are most alive, which blaze in the memory, are these tiny, rare moments of connection, even tragically imperfect connection, with the ghostly echo of Aphra’s lost people.

For me, the triumphant surprise of the story comes in the end, when Aphra approaches the cultists, and chooses to act. Specter’s descriptions of bodies hanging from trees, combined with our familiarity with the copes of creepy cults in Lovecraft and outside, prepare us mid-story to expect that when Aphra approaches the cult they’ll be evil and insane, and she’ll overcome her resentment of the government and do what has to be done. Or possibly the reversal will be stronger with that, and the cult will be good and nice, like Aphra, and the take-home message will be that Specter is wrong and Aphra and the cultists are all just misunderstood and oppressed. It feels like the latter is where the story will take us when we see Wilder and Bergman, and Aphra finds comfort and companionship in participating in a badly-pronounced imitation of her native religion. Even when we hear about the immortality ritual and Bergman refuses to listen to Aphra’s attempts to make her see that her ambition is an illusion, it still feels like we are in the narrative where the cultists are good but misunderstood, and the tragedy is just that there is such deep racial misunderstanding that even Cthulhu-worshipping Bergman cannot believe Aphra’s attempts to help her are sincere. It is a real shock, then, when Aphra called in Specter to shut the group down, because the genre setting raises such a firm expectation that “bad cultist” = “blood and gore” that even when we read about Bergman’s two drowned predecessors it doesn’t register as “human sacrifice” or “bad cult.” Aphra, unlike the reader, is unclouded by genre expectations, and shows us that, precious as this echo of her lost culture is to her, life is more precious still and requires action. The ghostly echo of Aphra’s people that she shares with Charlie is precious enough to blaze in her memory, but she is willing to sacrifice the far more welcome possibility of being an actual priestess for people who sincerely want to share her religion, when she realizes that their cultural misunderstanding will cost human lives. And she cares this deeply despite being an immortal among mortals. The triumph of empathy is complete.

Unlike the numerous vampire stories and other tales which so often present immortals seeing themselves as different, special, unapproachable, and usually superior to mortals, here Aphra’s potential immortality enhances the uniqueness of her perspective and the depth of her loss, but without in any way diminishing her respect for and valuation of the short-lived humans that surround her. The grotesque folder of experimental records which is her mother’s cenotaph does make her reflect on how the loss is greater than the human murderers understood, but does not make her present it as fundamentally different from the deaths of humans, or make her (or us) see her suffering in any way more important or special than that of the Japanese family with whom she lives. The history of Earth that her people have learned from the Yith make her recognize that living until the sun dies is not forever, nor is even the lifespan of the planet-hopping Yith who will persist until the universe has run out of stars and ages to colonize. The Litany of Earth that she shares with Charlie is an equalizer, enabling empathy across even boundaries of mortality by placing finite and indefinite life coequally face-to-face with the ultimate challenges of entropy, extinction and the desire to find something valuable to cling to. “At least the effort is real.” This is something Charlie has despite his failing body, that Aphra’s brother has despite his deprived education, that Aphra has despite her painful solitude, a continuity that overcomes the tragic discontinuity and connects Aphra even with her lost parents, with ancestors, descendants, with forgotten races, races that have not yet evolved, races on distant worlds, races in distant aeons, and with the reader.

One last facet I want to comment on is how the story portrays magic which is at the same time viscerally bodily and also beautiful and positive. This is very unusual, and the more you know about the history of magic the clearer that becomes. Magic, at least positive magic, is much more frequently depicted with connections to the immaterial and spiritual than the bodily: bolts of light, glowing auras, floating illusions, the spirits of great wizards powerfully transcending their age-worn mortal husks. Magical effects that are bodily, using blood, distorting flesh, are usually bad, evil cultism, witchcraft. This trope far predates modern fantasy writing. I have documents from the Renaissance based on ones from Greece discussing magic and differentiating between the good kind which is based on study, scholarship, texts, words of power, perfection of the mind, the soul transcending the body, angelic flight, spiritual messengers, rays and auras of divine power, an intellectual, disembodied and male-dominated “good” magic contrasted, in the same types of texts, with the bad evil magic of ritual sacrifice, sexuality, animal forms, distortion of the body, contagion, blood and associated with witchcraft and with women. Cultural baggage from the Middle Ages is hard to break from even now, and we see this in the palette of special effects Hollywood reserves for good wizards and bad wizards. The tender, intimate, visceral but beautiful magic which Ruthanna Emrys has presented is authentic to Lovecraft and to the rituals we associate with “dark arts” and yet positive, a rehabilitation which works in powerful symbiosis with the story’s treatments of discrimination. Since race and religion are so much in the center of the story, its treatment of gender rarely takes center stage, but in these depictions of magic especially it is potent nonetheless.

I’ll stop discussing the story here, since I resolved to make this review shorter than the story itself, and I’m running close to breaking that resolution.

Step Seven: Sing.

One of the most conspicuous effects when I first read “The Litany of Earth” was that it made me get one of my own songs firmly stuck in my head for many, many hours. The piece is “Longer in Stories than Stone” and it is the big finale chorus to my Viking song cycle, a piece about the fragility of memory and the importance of historical transmission. It is a different treatment but with similar themes, and I found that listening to it a few times live and over and over in my head helped me extend the feelings reading the story awoke in me, and let me continue to enjoy and contemplate its messages for several happy hours. So to celebrate the release of the story (taking advantage of the fact that this blog is no longer anonymous) here is the song, and I hope it will do for you what it did for me and help me extend my period of pleasurable mulling. I hope you enjoy:

If you want more stories by Ruthanna Emrys go here. If you want to other excellent short fiction on Tor.com with related themes I recommend “Anyway Angie” and “The Water That Falls On You From Nowhere”. If you want to see more amazing things Kurt Busiek does by giving P.O.V. to traditionally silenced facets of modern superhero comics beyond just Marvels, try Astro City or the original run of Thunderbolts. If you want to hear more of my Viking music, there’s some streaming on the Sassafrass site.

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)