Spot the Saint: Reparata and Zenobius

Since I talked recently about the Heavenly Court, comparing the office of Patron Saint to nobility holding landed titles, I would like to pause a moment to discuss Florence’s two former patron saints. Just as cities and counties move from noble house to noble house and dynasties replace each other over the course of meandering politics and war, so cities can change hands from saint to saint. John the baptist is not, in fact, Florence’s first patron saint, but its third (fourth, if you count the very early patronage of San Lorenzo).

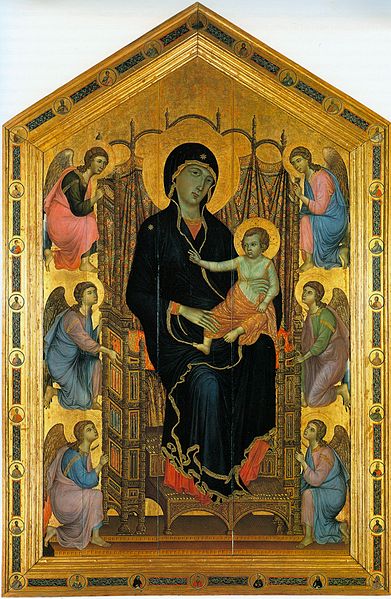

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)

- Common attributes: Crown, martyr’s palm frond

- Patron saint of: nothing specific, really

- Patron of places: Florence, Nice

- Feast days: October 8th

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints

- Relics: Nice Cathedral

Santa Reparata falls into that palette of early martyr saints which historians constantly point out may be mythical. If she existed, she did so in Caesaria in Palestine, and was martyred under Decius. She was saved from being burned alive by miraculous rain, was then forced to drink boiling pitch, but still refused to recant, so was beheaded. Thus she falls into the same general late Roman virgin martyr category as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, but was never nearly so popular. Her relics were (much later) brought to Nice.

Santa Reparata doesn’t have much distinctive iconography becuase she is a very obscure saint, and never depicted, really, except in her own territories of Florence and Nice. Much as you don’t find portraits of a low-ranking baron in faraway cities, you don’t find Santa Reparata in Rome and Paris, she’s just not high up enough in the heavenly court. She often has a crown–as martyrs frequently do–and a palm frond–ditto–but other than that she’s just a girl in late Roman clothes.

How then can you spot her? She’s one of the saints you have to sort by taxonomy, i.e. looking for generic attributes then using common sense. “There’s a woman here with a palm frond and no other attributes–wait, I’m in Florence, so it’s probably Reparata!”

Florence was Santa Reparata’s major cult site throughout the Middle Ages. Her church stood in the center of the city opposite the baptistery. When the growing power of Florence demanded a correspondingly large and impressive cathedral, and inclined them toward higher ranking patron saints, the city had to secure special permission to consecrate the replacement church to the Virgin. The Duomo stands on the former site of Santa Reparata, and parts of the original church are visible if you go down into the crypt. The Duomo which replaced it is Santa Maria del Fiore, St. Mary of Flowers, the flowers referring to the Florentine Lilly and the papal rose, since it was personally dedicated (and permitted) by Pope Eugene IV who was in town in 1436 doing, you know, pope things.

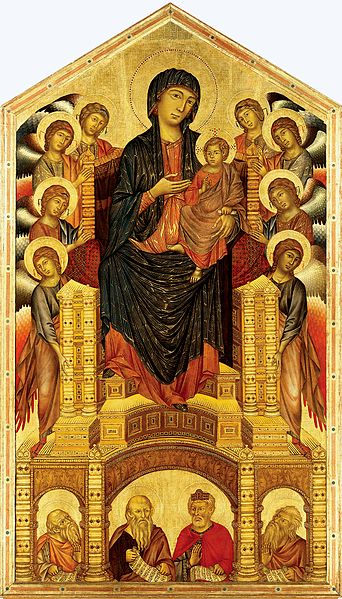

Saint Zenobius

- Common attributes: Bishop

- Occasional attributes: Florentine red fleur de lis, flowering tree

- Patron saint of: Florence

- Patron of places: Florence

- Feast days: May 25

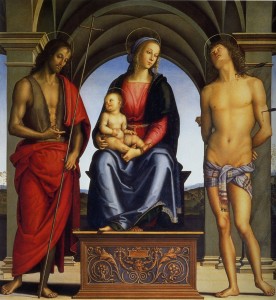

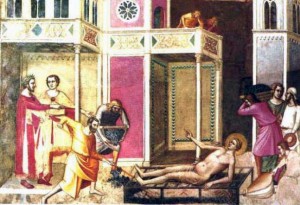

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, resurrecting somebody

- Close relationships: St. Ambrose, St. Eugene and St. Crescentius

- Relics: Florence, Santa Reparata crypt

Saint Zenobius was the first bishop of Florence. He supported St. Ambrose in battling the Arian heresy. He brought several people back from the dead, and his relics resurrected a dead elm tree. He used to be buried in San Lorenzo in Florence, but was later moved to Santa Reparata/the Duomo.

Saint Zenobius is one of these cases of an early Christian who did a good job and was pious and therefore got to be a saint just for that, without getting martyred or founding a giant order or anything. I support this, but it means his primary role was in Christianizing Florence and putting it on the map, so he is not and never will be particularly beloved outside his native town.

Zenobius is particularly valuable for Florence since he’s a saint who’s actually from Florence. The more one studies hagiography, the more one realizes that Florence had a rather embarassing paucity of saints. Milan had Ambrose, Padua had Antony, Verona had Peter Martyr, Sienna had Bernardino and Catherine, Assisi had Francis and Claire, Dominic died in Bologna, even Pisa had Rainerius, while Florence… Florence…

There was that one time Peter Martyr dropped by and defeated a possessed horse, and Francis and Dominic visited, and Bernardino of Sienna, but with such illustrious saintly neighbors, many from less powerful cities, Florence really needed a local saint, not just a patron but an actual Florentine, or it frankly looked bad. Florence was one of the five largest cities on Earth during the Renaissance–shouldn’t it produce at least one local saint? And the fact that the Medici had arranged for the city to bury the infamous antipope John XXIII in the Baptistery didn’t help matters.

The Florentines made a decent sainthood case for Dante (which I heartily support), and the optimistic Dominicans at San Marco have carefully preserved the relics of Savonarola just in case, but getting someone made a saint requires approval from the pope, and both Dante and Savonarola were… how to put this delicately… well, Dante made a special place in Hell for popes and wanted the papacy’s earthly power to be overthrown by the Empire, while Savonarola declared that the pope was the Antichrist (which, given that the pope in question was Alexander VI, aka. Roderigo Borgia, may not have been far off, but it didn’t exactly endear Savonarola to said Antichrist’s successors, nor did the fact that Savonarola’s writings were so popular with Reformation leaders). So both Florence’s leading candidates for sainthood were flatly on the wrong side of the official approval process. Plus Dante was banished from Florence, so his relics are in Ravenna (not helpful), and the Florentines killed Savonarola, and he was from Ferrara originally anyway. Not the best show, oh magnificant republic, and not the best P.R. situation for a city which already had a reputation as a bizarre and wicked sin-pit, whose economy was based on usury, whose greatest poet and saint-candidate declared that Florence’s name was famous throughout Hell, and whose name in verb form (“Fiorentinare” i.e. make like a Florentine) genuinely was a medieval euphemism for sodomy across Europe. So, Saint Zenobius it is!

Zenobius, in partnership with Reparata and, to a lesser extent, Lorenzo, were the city’s patrons for many centuries. Eventually Florence increased in importance (and relic possession) and the city became one of the territories possessed by that most favored of courtiers (and cousin to the King!) John the Baptist. But, like any good fiefdom, Florence still honors its lower local patrons too.

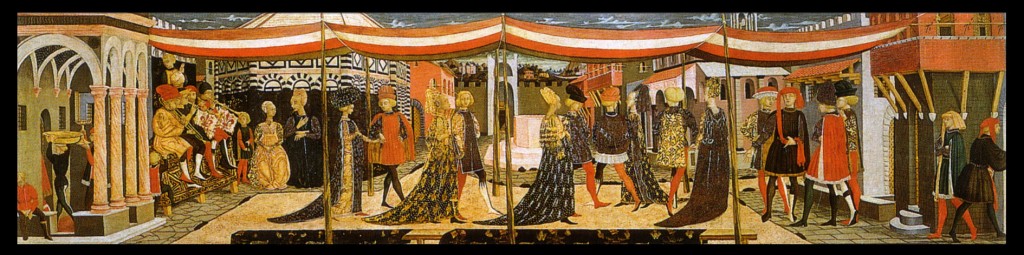

Zenobius is impossible to recognize in art most of the time, since he has no unique attributes. Even the facade of the Duomo had to label him so people would be sure. He was a bishop, so he dresses like a bishop, but so do at least fifty other saints. Sometimes he has a flowering branch, representing his resurrected elm tree, which helps, but usually all you can do is say, “I’m in Florence and there’s an unidentified bishop saint; maybe Zenobius?” Occasionally a Florentine red fleur de lis is put on his clothing somewhere as a clue, but not always, and the fleur de lis wasn’t a Florentine symbol until many centuries after Zenobius’ death.

Saint Zenobius had two deacons who worked for him, Eugene and Crescentius. They also get to be saints, because they worked hard and did a good job (reason enough for me). They dress like deacons (i.e. like San Lorenzo does) and are easily recognizable because if St. Zenobius is standing around with two guys dressed like deacons then they’re Eugene and Crescentius; they are never depicted in any other contexts.

We now have our set of Florentine saints. If you see a painting or mosaic that has Lorenzo and John the Baptist and a random bishop and a woman with a crown and martyr’s palm and nothing else, it’s a pretty certain guarantee that it was made in Florence.

AND NOW, QUIZ YOURSELF ON SAINTS YOU KNOW SO FAR: