A Chance to Support Ex Urbe; Military Compass

Periodically readers ask me if there is a “tip jar” or other way to support Ex Urbe and say thank you for my work. Normally the answer is no, I do it out of pure enjoyment and the desire to share the places and periods I study. But short-term there is a way.

I compose music (polyphonic a cappella and mythology-themed folk music), and have just launched a kickstarter to raise money for my next project. I have been working on this set of songs for ten years, and have given my mythological subject the same care I have given the Renaissance in my posts, so it has come together to be quite something (though I do say so myself). I can’t post a direct link here because I still want to preserve the public anonymity of this blog, but if any readers would like to support me, or check out the project, please e-mail me (JEDDMason at gmail dot com) and I will send you the link. Thank you.

Meanwhile, for your enjoyment…

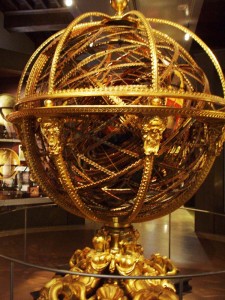

I want to introduce you to my favorite artifact at the “Museo Galileo,” the Florentine museum of the History of Science. It is a unique artifact, a “Military Compass.” Designed in the seventeenth century, it is the epitome of a gentleman’s weapon: a dagger which splits apart to become a geometric compass, so the educated wielder can use it to measure ground, calculate the sizes of fortresses, distances, and aim artillery:

A hinge in the hilt allows the blade to snap apart. The two halves are marked as rulers, and a weight drops out of the handle into the center to form a central measure, making it possible to use it as a compass, a level and for many other types of calculations. The pommel flips open to reveal a small magnetic compass, and pieces fold out from inside the hollow blade to provide additional tools for calculation. But if it is folded up, it is as deadly as a dagger should be. Such weapons were far from commonplace, more curiosities, status symbols and showpieces, but they were certainly designed to be usable. We have records of them as early as the 16th century, when one was designed for a Medici commander.

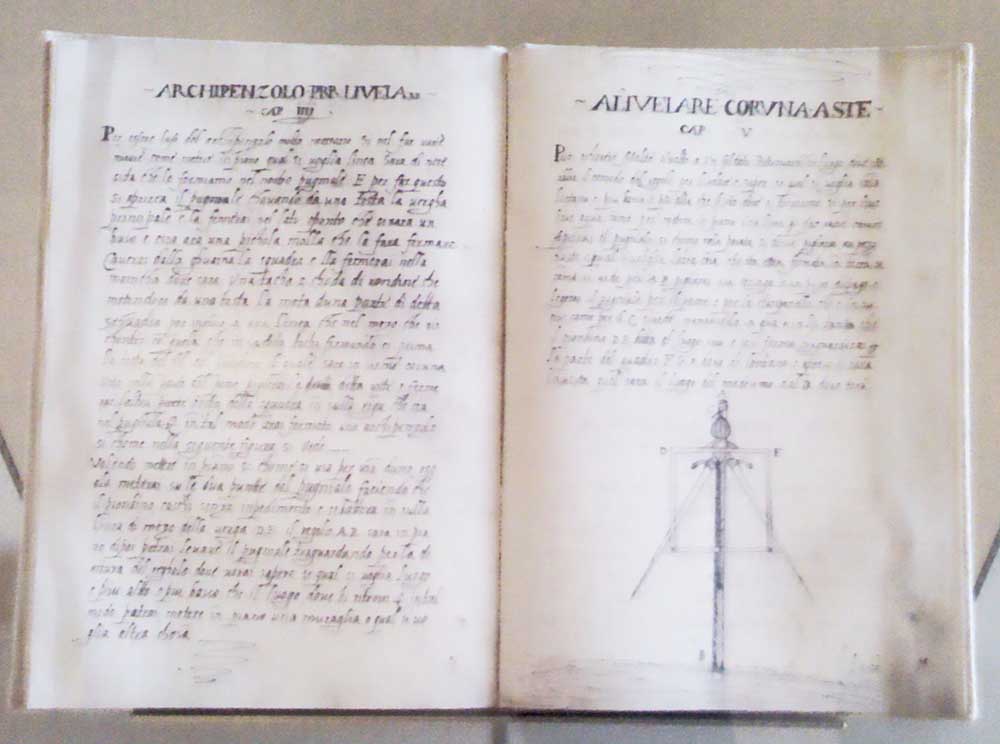

Instructions for the use of such a weapon are preserved in an anonymous 16th century Italian manuscript, also on display:

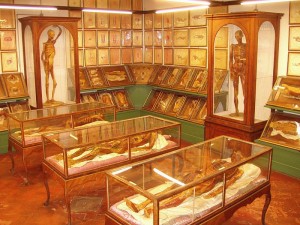

The museum also preserves other gentlemen’s instruments, such as walking sticks with concealed barometers, telescopes and other paraphernalia far more impressive than a cane-sword, but this one has always caught my imagination as something which encapsulates the ideal of the warrior-scholar-adventurer-noble which is so much at the heart of romantic notions of the “Renaissance man”, both our notions and the ideals they had in the period. I want to read a book where the protagonist carries this. I want to read ten books where the protagonist carries this. Also, as a reminder that the past never fails to sex-segregate no matter how unnecessary it is, they also have items intended for ladies of the period at the museum, including a “lady’s microscope” which is petite, delicate and carved out of ivory.