Spot the Saint: John the Baptist and Lorenzo (Begins Spot the Saint Series)

In galleries, museums, and even on the art-spotted streets of Florence, friends and I love to play “Spot the Saint” – trying to identify the saints in art without looking at the blurb. I know it sounds flippant to make a game of it, and perhaps it is flippant, but it is also in an important way authentic. Renaissance art, religious art especially, is aesthetic, but it is also narrative. Sculptures, paintings and other artifacts were created to retell and comment on stories and people whom the audience was expected to already know. Being able to identify different subjects, especially saints, by their vocabulary of recurring attributes is a kind of cultural literacy which all Renaissance people had, but most modern viewers lack. We are the illiterate ones, from the Renaissance perspective, when we come to an altarpiece unable to tell Paul from Peter or Augustine from Jerome. If you understand who these figures are and what they mean, a whole world of details, subtleties and comments present in the paintings come to light which are completely obscure if you don’t understand the subject. Time after time I’ve taken friends, who didn’t have much interest in Renaissance or religious art before, and after a few rounds of “Spot the Saint” in the Uffizi had them declare that it suddenly made a lot more sense, and carried a lot more meaning.

Renaissance art often focuses on details that are absent from the main versions of stories, showing the emotional expressions and making you think about the experiences of secondary characters present at scenes (almost like fanfic, in fact).

There is a wonderful example which (curses!) the internet cannot supply me with a photo of, an altarpiece by Alessandro Gherardini housed in the elusive and rarely open Santo Spirito church, across the river. It shows Christ crowning the Virgin Mary (a very common scene) accompanied by St. Monica and St. Augustine.

(On Augustine see my post on the Doctors of the Church).

This is not in any way exciting until you think about the fact that Monica is Augustine’s mother, who watched patiently throughout his wild and chaotic youth (wild by any standards – he joined the Manichean cult, and ditched her in Italy while hitching a boat to Africa with no warning), but she kept on, patient and loving, until he finally—through his own independent studies—explored and eventually embraced the Christianity she loved so much, and became one of its great Doctors. The altarpiece makes you think about the touching parallel between the two mothers’ love for their sons, and how proud Monica would be in Heaven watching Augustine’s growing greatness, and eventually getting to present her beloved son to Mary and her beloved Son.

But if you can’t spot the saints, it’s all a bunch of random figures.

Recognizing saints is also valuable for figuring out who made a piece of art, and why. Even an expert in a lifetime can’t memorize every single Florentine art treasure and its history, but a layman in a few days can learn enough to tell from the contents and context of a painting how to read a lot about its past and goals. Some saints are specific to cities; see something with a prominent St. Mark and you can smell Venice, while St. Zenobius is never seen outside Florence. Some are specific to types of patrons: is your altarpiece full of Dominicans? Probably the church that commissioned it was too. Full of female saints flanking Mary Magdalene? It’s time to suspect it may have been commissioned for nuns, or by a female patron. Renaissance masterworks didn’t come down to the modern age with convenient explanatory tags already attached: we wrote them, and the historians who did so used these same clues to figure out their origins.

Thus, this will be the first of many “Spot the Saint” posts, by which I hope to introduce the characters and thus open up the story of the art I see every day. Each entry will introduce a couple of new saints and how to recognize them, so we can all play, and understand. Since I am in Florence, I will concentrate first on the saints I see every day:

One friend, through more rigorous online hunting than my own, has very kindly provided this low-quality and slightly blurry photo of the altarpiece of Augustine and Monica at the coronation of the Virgin which I discussed above.

Santo Spirito, the church where it is housed, strives to fulfill its mission to protect the church from dangerous activities, like people going to it, looking at its art, or taking decent pictures of its treasures. I love to visit it, both for the gorgeous contents and architecture, and to spite its over-zealous guardians. It’s easier to go in these days, but a few years ago you practically had to have a Florentine accent to be admitted.

San Giovanni Baptista (St. John the Baptist )

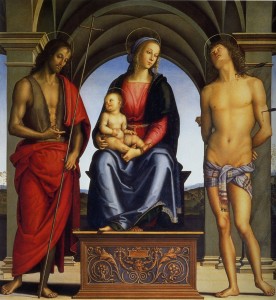

- Common attributes: Hairshirt, robes, tall stick with a cross on it, wild medium-length hair

- Occasional attributes: Beard, scroll saying “Ecce agnus dei”, pointing at things, sheep or lamb, rarely a book or something with a lamb on it

- Patron saint of: baptism, lambs, horse hoof care, printers, tailors, invoked to combat epilepsy and hailstorms (some of these are shared with several others, as is often the case).

- Patron of places: Florence, Turin, Genoa, Cesena, Umbria, a zillion other Italian towns,Jordan, Puerto Rico, Newfoundland, French Canada

- Feast days: June 24, August 29, January 7

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, baptizing Christ, pointing at Christ, pointing at viewer, pointing at heaven, visiting young Christ when they’re both kids, standing at the left hand of Christ during the apocalypse and overseeing the sorting of those damned to Hell, being imprisoned by King Herod, being beheaded, having his severed head delivered to Salome on a silver platter.

-

Here he’s pointing at the baby Jesus, lest the viewer, like Mary, be distracted by ever-distracting Saint Sebastian. Close relationships: Christ’s second cousin, son of Mary’s much older cousin Elisabeth and of Zachariah (both descended from Aaron); birth prophesied by Gabriel.

- Relics: Scattered around. His tomb is in Egypt, but his head is in Rome and Munich and Damascus and Bavaria and many other places. Florence has his right index finger and part of a forearm.

John the Baptist is an intimidatingly-important saint.

Not only is he a blood relative of Christ, and the pioneer of baptism, his grim task at the resurrection is vividly depicted in the numerous Last Judgment images which traditionally decorate the rear walls of churches.

And if Mary is so important partly because of her role as the kind protector sitting at the right hand of Christ to mitigate the wrath and protecting her faithful during the second coming, John the Baptist does the opposite. I certainly wouldn’t want to tick off a city under his personal protection.

As Florence’s patron saint and protector, John the Baptist appears all over the place in Florentine art, and they never tire of painting him pointing at things, both to remind the viewer of his importance as the one who “points the way” to Christ, but also because they have that finger. You can still see it, in fact, in the Museo del Opera del Duomo, but it used to be housed in the Baptistery, which is the historic heart and symbol of the city.

And a place that made a strong impression on a certain Dante when he was a little boy.

The main thing for spotting John the Baptist, though, is the hairshirt, depicted as some kind of fuzzy fur. Sometimes it’s under a robe, sometimes it’s all he’s wearing. Even in bronze or stone, it’s always clear:

San Lorenzo (St. Lawrence)

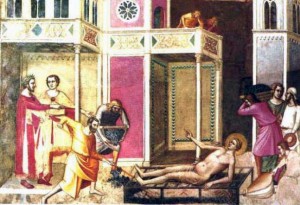

- Common attributes: carries an enormous iron grill, dressed as a deacon (wearing a dalmatic tunic), short, tonsured hair

- Occasional attributes: palm frond (any martyr can carry a palm frond), often dressed in red or pink

- Patron saint of: cooking, chefs, barbeque, librarians, libraries, notaries, administrators, tanners, paupers, comedians, some other things

- Patron of places: Rome, Canada, Rotterdam, Sri Lanka, Canada

- Patron of people: Medici Family

- Feast Day: August 10th

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, being roasted alive, being sentenced to death by the Emperor Vespasian, distributing alms to the poor

- Close Relationships: He’s one of the Deacons of the Church who oversaw its finances in early days, so is associated with other early deacons, and early martyrs, like St. Stephen

- Relics: They burned him so there are only bits. Florence has some. The grill is in Rome.

I already discussed San Lorenzo and his most excellent patronage of the poor in my post about the celebrations of his feast day. As a prominent early martyr he is very commonly depicted with other martyrs.

He’s a favorite in Florence because he was a keeper of money, and the many moneylenders of the Italian banking circuit (not least the Medici) were eager for examples of virtuous people who dealt with money, so they could justify their financial obsessions and deflect accusations of usury. That a man who was grilled alive is patron saint of cooking and specifically roasting and barbeque proves there is a sense of humor to these things, as does the fact that his witty last words, “Flip me over, Caesar, I’m done on this side,” earned him eternal fame as Patron Saint of Comedians. True grace under (over?) fire. Also: patron of cooking AND libraries? There’s a saint dear to my heart.