Sketches of a History of Skepticism, Part II: Classical Hybrids

Come to rescue us from the dark and gloomy wood of Doubt in which we have been wandering since my first post in this series (did you say hello to Dante?) comes the Criterion of Truth! The idea that, while the skeptics are correct that logic and the senses sometimes fail, they do not always fail, and if we carefully study when they fail, and why, if we identify the source of error, we can differentiate reliable knowledge from unreliable knowledge. For example, our eyes may deceive us when we judge a stick half-submerged in water to be bent, but if we add the testimony of other senses (touch), and of repeated experience (last time we saw an object half-way into water) we can identify the error, and henceforth say that we will not trust sense data based on visual information about objects half-submerged in transparent liquids, but that other sense data may be reliable. Once the causes of error have been defined, once we have a criterion for judging when knowledge is uncertain and when it is reliable, if we thereafter base our conclusions only on what we know is certain, then our conclusions will be reliable, eternal and divine, a steady foundation upon which we may proceed in safety toward that godlike happiness we seek. The Criterion of Truth is the clean and steady light of compromise, which does not banish all shadow, but, like a lantern in the dark, allows a philosophical system to have dogmatic elements while still conceding that much remains in shadow.

Come to rescue us from the dark and gloomy wood of Doubt in which we have been wandering since my first post in this series (did you say hello to Dante?) comes the Criterion of Truth! The idea that, while the skeptics are correct that logic and the senses sometimes fail, they do not always fail, and if we carefully study when they fail, and why, if we identify the source of error, we can differentiate reliable knowledge from unreliable knowledge. For example, our eyes may deceive us when we judge a stick half-submerged in water to be bent, but if we add the testimony of other senses (touch), and of repeated experience (last time we saw an object half-way into water) we can identify the error, and henceforth say that we will not trust sense data based on visual information about objects half-submerged in transparent liquids, but that other sense data may be reliable. Once the causes of error have been defined, once we have a criterion for judging when knowledge is uncertain and when it is reliable, if we thereafter base our conclusions only on what we know is certain, then our conclusions will be reliable, eternal and divine, a steady foundation upon which we may proceed in safety toward that godlike happiness we seek. The Criterion of Truth is the clean and steady light of compromise, which does not banish all shadow, but, like a lantern in the dark, allows a philosophical system to have dogmatic elements while still conceding that much remains in shadow.

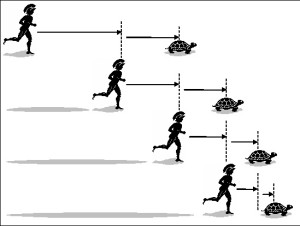

“Quite wrong!” cries our Pyrrhonist. “You have it all backwards! Doubt is the steady path toward eudaimonia. The absence of the possibility of certainty is our liberation, not our bane! It is when we embrace the fact that we cannot have certainty that we are finally free from the risk of having our beliefs overturned and our Plutos and Brontosaurs snatched away. It is when truth is firmly beyond human reach that we can finally relax and stop being plagued by curiosity and the endless, restless quest for information. The Criterion of Truth is not a light in darkness, it is a battering ram which has pierced our clean and serene sanctum and smeared it with all the muddled and confusing chaos that we worked so hard to banish! Don’t build a path on this foundation! However steady it may seem, the ground could still give way at any moment and shatter all. And even if it doesn’t, the path will never end. You will exhaust yourself on its construction, your age-gnarled hands still struggling to lay stones when you breathe your last, with never a glimpse of the end in sight, just infinity of toil and darkness. And the you will inflict the same curse upon your children, and your children’s children, and your children’s, children’s, children’s children!”

“Quite wrong!” cries our Pyrrhonist. “You have it all backwards! Doubt is the steady path toward eudaimonia. The absence of the possibility of certainty is our liberation, not our bane! It is when we embrace the fact that we cannot have certainty that we are finally free from the risk of having our beliefs overturned and our Plutos and Brontosaurs snatched away. It is when truth is firmly beyond human reach that we can finally relax and stop being plagued by curiosity and the endless, restless quest for information. The Criterion of Truth is not a light in darkness, it is a battering ram which has pierced our clean and serene sanctum and smeared it with all the muddled and confusing chaos that we worked so hard to banish! Don’t build a path on this foundation! However steady it may seem, the ground could still give way at any moment and shatter all. And even if it doesn’t, the path will never end. You will exhaust yourself on its construction, your age-gnarled hands still struggling to lay stones when you breathe your last, with never a glimpse of the end in sight, just infinity of toil and darkness. And the you will inflict the same curse upon your children, and your children’s children, and your children’s, children’s, children’s children!”

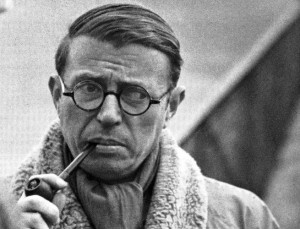

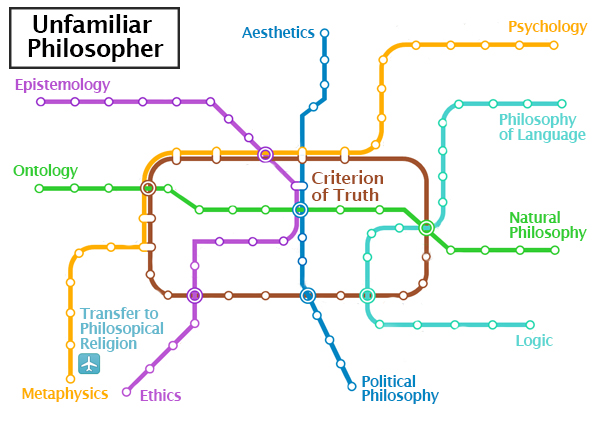

Whether one sees it as a blessing or a curse, developing a Criterion of Truth is what has allowed, and still allows, dogmatic philosophical systems to exist and progress in a fertile and symbiotic relationship with skepticism, instead of ending with the blank serenity where Pyrrho and other absolute skeptics wanted to dwell forever. Every philosopher with any dogmatic ideas has a criterion of truth (“Yes, even you, Sartre,” says Descartes, “Don’t give me that look!”), and an explanation for the source of error, and frequently I find that, when I am feeling awash in the ideas of a new thinker, one of the best ways to start to get a grip on things is to find the criterion of truth, which gives me an anchor point from which to explore, and to compare that thinker to others I am more familiar with.

Whether one sees it as a blessing or a curse, developing a Criterion of Truth is what has allowed, and still allows, dogmatic philosophical systems to exist and progress in a fertile and symbiotic relationship with skepticism, instead of ending with the blank serenity where Pyrrho and other absolute skeptics wanted to dwell forever. Every philosopher with any dogmatic ideas has a criterion of truth (“Yes, even you, Sartre,” says Descartes, “Don’t give me that look!”), and an explanation for the source of error, and frequently I find that, when I am feeling awash in the ideas of a new thinker, one of the best ways to start to get a grip on things is to find the criterion of truth, which gives me an anchor point from which to explore, and to compare that thinker to others I am more familiar with.

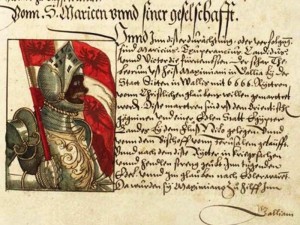

Today I shall attempt something a bit compressed but hopefully the compression itself will be fruitful. I intend to briefly examine three of the major classical schools (Platonism, Aristotelianism and Epicureanism) and explain just enough of each system to make clear its criterion of truth and its explanation for the source of error. By laying these out in a compressed form, side-by-side, I hope to show clearly how skepticism is at play in each of the dogmatic systems, and to show what the early approaches to it were, so that when I move forward to major turning points in skepticism it will be clearer just how new and different the new, different things are. Tradition dictates that I start with Platonism, but Socrates is looking a little too aggressively eager now that I mention Plato, and furthermore he was being mean to Sartre while we were away (Don’t pretend you didn’t know that dialog trying to define “being” would make him cry!), so I shall instead start with Epicurus:

The Epicurean Criterion of Truth: Weak Empiricism

The Epicurean Criterion of Truth: Weak Empiricism

Take the stick out of the water. Epicureanism faces up to the skeptical challenge to the reliability of sense data and still chooses to promote the senses as our primary source of information, simply proposing that we should not rely upon first impressions, but should consider sense data reliable only after careful investigation, ideally using multiple senses and instances of observation. But there is more to it than that.

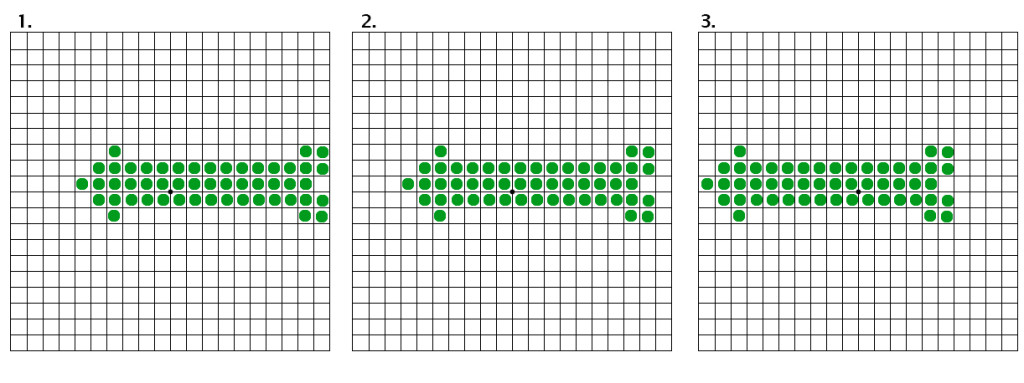

Epicureanism is a mature form of classical atomism, positing that on the micro-level matter is composed of a mixture of vacuum and invisibly tiny, individual components or seeds known as “atoms” which exist in infinite supply but finite varieties (see the modern Periodic Table), and that the substances and patterns we see in nature are caused by different recurring combinations of these atoms. If the same kind of sand appears on two unrelated beaches, it is composed by chance of the same combination of atoms. If a piece of wood is burned and goes from being brown, firm and porous to being white and powdery, some atoms have left it (in the smoke, for example), and the remaining ones look different.

Atoms too are responsible for the apparently changeable properties of objects (remember the seventh mode of Pyrrhonism, that we cannot have certainty because objects take multiple forms). The properties of substances do not derive from atoms themselves but from their combinations. Colors, smells and flavors are all effects of the shapes of atoms, so it is not true that sweet substances contain sweet atoms and red substances red atoms, rather sweet substances contain smooth atoms which are pleasant to the tongue rather than rough, and red objects contain atoms whose combinations create redness. If bronze is red and then turns green, or wood is brown but burns and turns gray, then atoms have entered or left and the new combinations create a different color. And it is on this atomic basis that the Epicureans argue that (a) natural interactions of atoms and vacuum are enough by themselves to explain all observed phenomena, so there is no need to posit fearsome interfering gods, and (b) the soul is just a collection of very fine atoms, distributed in the body and breath, which disperse at death, so there is no need to fear a punitive afterlife.

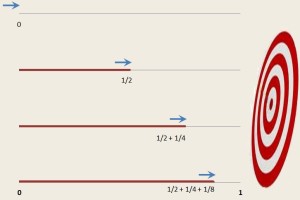

Atoms are, believe it or not, largely a solution to Zeno’s paradoxes of motion, and also have much to say about our stick in water. As we all recall, Zeno’s arrow can never reach its target because the space in between can be infinitely subdivided into smaller distances which it must cross before it can finish its path, therefore motion is impossible. Epicurus answers: yes. Motion is indeed impossible. Motion is an illusion. The key is that space is not infinitely divisible, as Zeno proposed. Atoms, according to the Epicurean system, are not only the smallest objects but the smallest subdivision of space; it is literally impossible to subdivide either atoms or space further. (Note that if he were around now Epicurus would deny that our modern “atoms” are atoms – he would confer that title upon the smallest known sub-atomic particle, or reserve it for the piece smaller than that which all the king’s horses and all the king’s cyclotrons still can’t detect.) The smallest distance any object can move is one atom-width – any more nuanced motion is impossible. In other words, fluid motion is an illusion, and on the micro-level objects do not slide from one place to another. Rather their atoms pop in an instant from one position to the next atom-width over. One might call it microscopic teleportation. It is by this means that the arrow moves: every component atom in the arrow teleports one space to the left each moment, and thus the arrow proceeds from right to left sequentially.

Positing micro-teleportation as a substitute for motion may seem alien, but it is something we make use of every day in the modern world, and it is in fact much easier to explain Epicurean theories of motion to modern computer-users than it was to people in the past. As you scroll down this page, the cursor of your mouse and the text on the screen seem to move, but in fact nothing is moving. Instead tiny pixels, the atom-widths of your screen, are changing color, or you could say that the black pixels that form the text are teleporting one pixel-width per moment as you scroll. The eye, unable to see such fine distinctions, blurs that micro-teleportation into the illusion of motion. Why couldn’t all motion be a similar illusion? Zeno is defeated, and Reason is once again reliable.

Which is good because Reason is the heart of the system of knowledge Epicurus wants to build. The Epicurean atomic theory, after all, is based on a combination of observations of the sensible world and then logical deductions. We observe that objects change their form when burned, that sea-soaked cloth hung up to dry becomes dry but remains salty, and that the same types of substances recur in many independent locations. From this we deduce the existence of atoms of different types in different combinations without ever directly seeing them. Zeno’s paradox of motion does not, in this interpretation, demonstrate that we can’t trust reason, but that we can’t trust rash, unexamined observations. There seemed to be motion, but with time, patience, observation and reason the Epicurean has determined that that was a mistake, and found a better model.

But this does an interesting thing to sense data, which Epicurus still wants to be more our guide than naked logic. Atomism, which predates Epicurus, seems to have itself arisen from observations of motes in a sunbeam, tiny particles which are invisible normally but visible only in special circumstances, and which all classical atomists cite as sensory evidence for the reality of atoms. From motes in a sunbeam and raw logic, they derive the atomic theory. As Epicureans strive to free themselves from fear of the unknown by observing and explaining natural phenomena through the interaction of atoms, they rely on what they can see, feel, hear and touch to derive their theories. This is empiricism but it is (as Richard Popkin aptly named it) weak empiricism. Why? Because the reality beneath what we observe is invisible. (“Exactly!” cries Sartre, leaping up with sufficient force to knock over Descartes’ thermas.) If atoms are undetectably tiny, and everything we see, taste and smell is a consequence of their combinations rather than the atoms themselves, then we can never have real knowledge of the fundamental substructure of being. There is an insoluble barrier between us and knowledge of true things, the barrier of minuteness. Thus Epicurean empiricism involves surrendering forever any certain knowledge of the truth of things, but in return we can have fairly reliable knowledge based on careful, repeated observation using multiple senses, especially now that logic has been rescued from Zeno’s grasp and is once again our ally.

Source of Error: Twofold. Limitations of the senses, which cannot see atomic reality; unquestioned acceptance of sense data and commonplace cultural assumptions (like superstitions about the gods) which are unreliable because they are not based on careful observation and analysis.

Criterion of Truth: Knowledge is certain when it is based on a combination of careful observation of the sensible world with multiple senses, and careful logical analysis.

Zones of the Knowable and Unknowable: We can have true and certain knowledge of the observable world, and we can make rational deductions about the insensible world which are reliable enough to act upon (since we cannot ever prove or disprove them), but we cannot ever have true and certain knowledge of the invisible atomic world which is Nature’s true reality.

At this point some readers are not particularly disturbed by Epicurus’ surrender of true knowledge of microscopic things. After all, have advanced since 300 BC. We played with microscopes in grade school, we named the proton and the quark and preon, we made molecules out of toothpicks and gummy candies, and the electric blood of splitting atoms blazes in our lightbulbs. We fixed that weakness. “Delusion!” Sartre says, and he is right that, on a fundamental level, this technological advancement has not let us reclaim what Epicurus surrendered. However advanced our science, we still have no cause to believe we have yet perceived or even hypothesized the literally smallest increment of matter. And, separately, even if we had a machine capable of perceiving the smallest part of matter, we would still be limited by our senses since the machine would have to use our senses to transmit its findings to us, transmitting only an approximation, rather than reality. And in addition, the vast majority of our daily decisions would still be based on what we perceive at the macroscopic level. Thus, even with technological aid, the Epicurean surrender of knowledge of the fundamental seeds of things is a considerable one, and divides all knowledge firmly into two camps, the perceivable world about which it is possible to have certainty, and the reality beneath about which it is not. We have a path and shadows, dogmatism and skepticism coextant within one system.

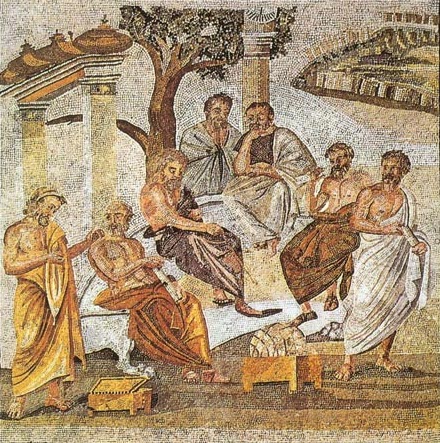

The Platonic Criterion of Truth: the Forms

My approach to Platonism will be rather sideways, but I want to get us to its criterion of truth by a route that is as parallel as possible to Epicurus’. So, for the vast majority of my readers who know basic Platonism already, please read along thinking about Zeno’s paradoxes and the stick in water how this way of outlining Platonism follows the same logical structure Epicurus did.

Plato, like the skeptics, acknowledges that the senses fail and deceive, and, like the atomists, observed that there are recognizable, recurring objects in nature that come into existence in independent parallel to one another: similar rocks, mountains, trees and animals in distant corners of the Earth, which must, he reasoned, have some common source. He also noticed that humans are able to recognize and identify these objects as being the same, even humans who have never met each other, or speak different languages, and even when the objects may have radically different colors and shapes disguising a shared structure – a disguise we see through. Finally he noticed (something Epicurus did not discuss) the fact that humans not only naturally identify objects, but naturally judge them to be better or worse based on unspoken but nonetheless universal criteria. Anyone can tell that a crisp, fresh apple is “better” and a withered, dry one “worse” without having to discuss or debate that fact, or even to be taught it. I could show you a healthy and a diseased version of some deep-sea fish you’ve never heard of and you would nonetheless successfully identify them as “better” and “worse” exemplars of a completely new and unknown thing.

To explain these patterns, and this universal capacity to identify and judge “better” and “worse” examples of things, Plato posited that these objects must have a shared source, but instead of positing a combination of atoms, he posited a source independent of matter that supplied the object’s structure. All quartz crystals, all trees, and all apples take their structures from a separate structure-supplying object, which exists independent of matter and time. It has to, since the objects it generates can come into existence and be destroyed, but the pattern, the archetype, the source remains. Plato named this structural archetype the “Form” and posited that these Forms exist in a separate level of reality. They create the many material manifestations of their structure as a flag pole might cast many shadows on different objects at different times. As some shadows are crisp, straight images of what casts them and others are vague, twisted or distorted, so objects are sometimes fairly straight and sometimes quite twisted manifestations of their Forms. When we judge an object, we judge it based on how good an image it is, how closely it resembles the Form which is the source of its structure. Hence why anyone of any age, in any culture, without the necessity of communication, can judge the superior of two apples, and tell that twisty trees are weird.

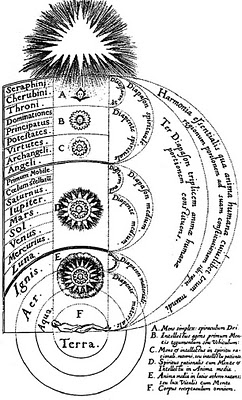

But objects are never truly like their Forms because Forms exist on a completely different level of reality, just as the flag pole exists on a different level of reality from its shadows. We know this the same way we know that the godlike eudaimonia we seek cannot be based on fleeting things like lust and truffles. Forms are indestructible – no matter how many trees or apples burn, the Form remains. With that attribute, in the Greek mind, go the others: Forms are eternal, unchanging, perfect, and divine. They cannot be part of this changing and destructible reality, but must exist on some other layer of reality where change and destruction do not exist. Note how this is in many ways exactly symmetrical to Epicurus’s atomic theory, in which atoms are indestructible, unchanging and perfect, and exist on an imperceptible micro-level accessible to us only by deduction, just as real-but-invisible as the Platonic realm of Forms. Both posit a materially inaccessible world which is the source of the structures of the perceivable world.

What about Zeno and the stick in water? Simple: the motions of a flagpole’s shadow across the earth and ground aren’t rational but bizarre, bending and distorting, split in half at times by passing objects, changing and imperfect. Just so the material world. The stick in water looks bent, and motion is rationally impossible, because the entire layer of reality perceived by the senses is itself bent, distorted, an imperfect effect of a perfect reality elsewhere. When we see the stick look bent, or realize that motion makes no sense, it is at that point that we are beginning to perceive the fundamental flaws in sensible reality, and realize that the true, rational, knowable structure lies elsewhere.

True knowledge, reliable, certain knowledge upon which we may build our path toward reliable, certain eudaimonia must therefore be knowledge of Forms, not of passing things. We can have True knowledge of the Form of Apples, the Form of Trees, the Form of Justice, the Form of Humans, but we cannot have true knowledge of a particular apple, tree, case of justice v. injustice, or human, because such things are changing, imperfect, and perishable, so even if we could know them perfectly at one instant, that knowledge would not be lasting, not enough to be a real foundation for happiness. The only permanent, certain knowledge is knowledge of eternal things, since all other knowledge is, like its objects, destructible. Thus the Forms are the path to Happiness.

And now, without any need to address the soul, or Platonic love, or Truth, or the other great Platonic signatures, we can describe the Platonic Criterion of Truth:

Source of Error: The material world perceived by the senses is imperfect and illusory, and conclusions based on observation of it are full of error, and incomplete.

Criterion of Truth: Knowledge is certain when it is based on knowledge of the eternal Forms, which can be perceived by Reason. So long as we rely only upon knowledge of abstract, eternal Forms and not on knowledge of specific material things, we will make no errors.

Zones of the Knowable and Unknowable: We can have true and certain knowledge of the Forms, i.e. of the eternal structures that create the sensible world, but we cannot ever have true and certain knowledge of individual objects within the material world.

Now, our friend Socrates has been waiting all this time to rant about how Plato put all this in his mouth, by using him as an interlocutor in his philosophical dialogs, when all Socrates stood for was the principle that we know nothing, and wisdom begins when we recognize that we know nothing. But explicated like this, in a way which highlights how substantial a portion of human experience Plato has yielded to the shadows of skeptical unknowability, Socrates has far less cause to object. Plato has taken “I know nothing” as his starting point, as, in fact, did Epicurus, both of them beginning by scrapping the received commonplaces of things people thought they knew about the material world, and instead trying to find a space for certainty far removed from the evidently-unknown world of daily experience. We all know that Plato tried to appropriate Socrates to his system, painting Socrates as a Platonist and implying that Socrates agreed with all Plato’s dogmatic ideas as well as his skeptical ones.

But Plato was far from the only one to do this. In the ancient world, Skeptics, Cynics, Stoics, Aristotelians and Neoplatonists all make claims about Socrates really believing what they believed, that Socrates was really a skeptic, or a stoic sage, etc. This is easy because Socrates left us nothing in his own voice, but also because all of them really did begin as he demanded, by doubting everything, declaring that “I know nothing” and then trying to work from that toward a system which carves out one zone for the knowable and surrenders another to the unknowable. Attempts by later sects to appropriate Socrates reflect his fame, but also their universal gratitude for the way his refinement of skepticism created a starting point from which they could approach their Criteria of Truth, and start from there to lay their foundations. And now that I’ve put it that way, Socrates seems much less set on picking a bone with Plato, and much more interested in the bones of the chicken drumsticks Sartre brought, which are much larger than those Descartes brought, which are larger than the ones Socrates is used to, a mystery which definitely bears investigation. We can in part blame one “Aristotle”, though when I mention him our more modern thinkers smile knowingly, thinking of the many stages that had to pass between the ancient empiricist and the alien concept “progress.”

The Aristotelian Criteria of Truth: Categories and Definitions

Aristotle studied with Plato for decades, and his framework has a similar beginning. Yes, we instantly recognize that apple is apple and cat is cat, even if we are on the other side of the world and recognize apple as ringo and cat as neko. And we instantly judge the withered apple as being farther from what an apple ought to be than the crisp one.

What Aristotle doesn’t like is how Plato has the Forms exist in a hypothetical immaterial reality removed from the sensible reality. Instead, he uses the term “form” to refer to structures within natural objects, which are not material but not immaterial either. They are non-material. This may sound like gibberish, but I recently demonstrated it very effectively to my class by taking two apples to the front of the classroom, setting them down while I had a drink of water, then violently smashing one of the apples with repeated blows from the butt end of the water glass, reducing it to a sticky green pulp and producing an extremely startled and, in the front rows, apple-bespattered classroom. “What did I just destroy?” I asked. It took only a few moments of recovery for one to supply: “The form of the apple.” Aristotle even goes so far as to say that forms, rather than matter, are what senses sense. When we see an apple our minds do not register the raw, chaotic matter, they register the structure: apple. When we see smashed apple pulp even then we do not see matter, we see pulp, which has its own structure. We never perceive matter, or rather never recognize matter, never understand matter. All cognition takes place on the level of form, which is why we can identify “apple” at a glance and not have to spend a minute assembling the millions of points of perceived light and color together to deduce that it’s an apple.

But if the form, for Aristotle, is a structure within individual objects, and is destructible, it can’t be a source of eternal certainty, nor can it explain how my colleague in Japan can recognize and judge apple identically to the way I do. For this Aristotle posits Categories. Universal categories exist in nature, non-material structures just like forms, into which the forms of objects fit. Human Reason is capable of identifying these categories, by looking at objects, understanding their forms, and identifying their commonalities, functions etc. We all see the apple and recognize that it fits in the category apple. We further recognize that the category apple fits in the category fruit, that in the category “part of a plant” etc. And that Stamen Apple is a sub-category within the category apple. This allows us to identify and judge even objects which we have never seen before and have no names for. You probably do not know at a glance what the creature pictured to the left here is, but you can identify that it belongs in the category mammal, possibly in the rodent category or maybe more like a tiny deer judging by those skinny legs, but certainly in the medium-sized, ground-dwelling, non-carnivore, probably scavenger eating fruit and bugs and things, not-dangerous-to-humans category. (It is, in fact, a Kanchil or “mouse-deer”). Similarly we can all categorize trees, rocks, fish, and other things. Aristotelian categories are part of Nature itself, eternal and unchanging, and indestructible, since the category apple and the category Kanchil will be unchanged regardless of the creation or destruction of any individual. A withered apple doesn’t harm the category apple, nor does a limping three-legged Kanchil, and the extinction of the T-Rex didn’t erase the category T-Rex.

But if the form, for Aristotle, is a structure within individual objects, and is destructible, it can’t be a source of eternal certainty, nor can it explain how my colleague in Japan can recognize and judge apple identically to the way I do. For this Aristotle posits Categories. Universal categories exist in nature, non-material structures just like forms, into which the forms of objects fit. Human Reason is capable of identifying these categories, by looking at objects, understanding their forms, and identifying their commonalities, functions etc. We all see the apple and recognize that it fits in the category apple. We further recognize that the category apple fits in the category fruit, that in the category “part of a plant” etc. And that Stamen Apple is a sub-category within the category apple. This allows us to identify and judge even objects which we have never seen before and have no names for. You probably do not know at a glance what the creature pictured to the left here is, but you can identify that it belongs in the category mammal, possibly in the rodent category or maybe more like a tiny deer judging by those skinny legs, but certainly in the medium-sized, ground-dwelling, non-carnivore, probably scavenger eating fruit and bugs and things, not-dangerous-to-humans category. (It is, in fact, a Kanchil or “mouse-deer”). Similarly we can all categorize trees, rocks, fish, and other things. Aristotelian categories are part of Nature itself, eternal and unchanging, and indestructible, since the category apple and the category Kanchil will be unchanged regardless of the creation or destruction of any individual. A withered apple doesn’t harm the category apple, nor does a limping three-legged Kanchil, and the extinction of the T-Rex didn’t erase the category T-Rex.

The extinction of the Brontosaur didn’t erase the category Brontosaur either – it was our discovery that the category was wrong that did so, and here we get toward Aristotle’s ideas of certainty and error. We had not defined our terms carefully enough, had accidentally separated two things that shouldn’t be, and thus were led to error. Error caused by insufficiently clear definitions of our terms. The categories are sources of true, certain and reliable knowledge. Like with Plato’s forms, we cannot Know-with-a-capital-K individual things with certainty, since they are destructible and changing, and the apple which is fresh today will be withered next week. But we can know the categories, and that it always has been and will be the nature of the apple to grow on trees and try to be sweet and colorful to attract animals to eat it and spread seeds, and that it always and will always be the nature of the T-Rex to be a humungous terrifying predator the sight of which inspires fear in all mammals and other smaller creatures. One source of error is when we make mistakes about categorization. We may mistake the Kanchil for a rodent, or a Vaquita for a dolphin, but with more careful observation we realize it is more closely related to a deer. We may mistake the Brontosaur for its own species before we realize it is a juvenile version of another thing, as easy a mistake to make as thinking that a caterpillar and butterfly are different creatures until we examine more closely. We also want to do this with things we may not, in modern parlance, think of as part of Nature, but just as there is the category “cetacean” within which exists the category “porpoise” so too there exist the category “integer” within which exists the category “prime number,” also the category “system of government” within which lies the category “democracy,” and the category “virtue” within which exists the category “justice.” Aristotle, and the rest of Greece with him, does not draw our modern post-Rousseau line between “Natural” and “artificial” placing human works in the latter. Birds are part of Nature, as are humans; birds’ nests are part of Nature, with a category, as are all the things humans create. The category “web page” which contains the category “blog” is as natural as the category “tree”.

Thus Aristotelian certainty comes with careful, systematic investigation of the categories within nature, and if we want to reduce error we can do so best by studying and measuring and comparing objects we see until we can fit them into categories. The more we study, and the more carefully we define our terms, the clearer our conversations will become, less given to assumptions, misunderstandings and error. One source of error, therefore, is equivocal language, words that are sloppily defined and don’t refer to real categories in nature. Brontosaur, planet, motion, Justice, good, are all sloppily-defined terms. Any term which does not point to a real category in Nature is sloppy and may lead us to error. If we use only vocabulary that is carefully worked through and points only at real categories, then our language will be clear, our communication perfect, and the possibility of error greatly reduced. After all, we only want to be talking about categories, not anything that isn’t one. Since, as with Plato’s forms, categories are eternal, unchanging and reliable. On their foundation we can build our path. As with Plato and Epicurus we have surrendered knowledge of individuals, in favor of knowledge of something structural which underlies them.

Excuse me: to proceed farther with Aristotle, I need to go get my fork. Here it is. (Or rather an image of it, one level less real, its Platonic shadow.)

This fork has been part of my life since I was a tiny girl, and it taught me about the Aristotelian sources of error. When I was little, I would help put the silverware away. This fork puzzled me. Why? Because I couldn’t figure out how to categorize it.

Here you see my dilemma. We had one slot for forks, which had tines and metal handles. And one slot for knives, which had blades and wooden handles. Where then goes this fork, which has tines but a wooden handle? Let’s offer the dilemma to our Youth.

- Youth: “I think it should go with the metal-handled fork.

- Socrates: “Why?”

- Youth: “Because it’s a fork. It’s used for fork things, that’s more important than what it’s made of.”

*Ding!*Ding!*Ding!* Correct! The Youth, like my child self, has correctly identified the Aristotelian distinction between an “essential property” and an “accidental property”. An essential property is a quality of something essential to it being itself, and filling the function it has in Nature; an accidental property is something that could change and it wouldn’t matter. A cat can be black or tabby (accidental) but must be slinky, carnivorous, and endearing to its owner in order to fulfill the functions of a cat. A tree must grow a woody trunk and produce leaves in order to fulfill the functions of a tree. A fork must fit comfortably in my hand and lift chunks of food to my mouth for it to be a fork. If the cat is orange, the tree is forked, and the fork is a futuristic rod that lifts food using a miniature tractor-beam instead of tines, those are accidents. If these things fulfill these functions badly–if a cat is ugly, a tree is all bent and twisted and produces few leaves, or a plastic fork snaps when I try to skewer food with it–we judge them bad examples of what they are. If these things don’t fill these functions at all–a quadrupedal mammal eats grass, a plant produces a soft viny stalk, and a piece of silverware cuts food in half instead of lifting it–we judge they do not belong in the categories cat, tree and fork respectively because they lack their essential properties. If I had mistakenly stored my wooden-handled fork with knives, that would have produced error, the same source of error as when we mistake a Kamchil for a rodent, or when Descartes, living in the 17th century, reads an article about how people from Africa are not the same as people from Europe because their skin is a different color. Mistaking accidental properties for essential ones has introduced error. And to call a robot toy a “cat”, or a metaphor for understanding genealogy a “tree”, or a fifteen-foot fork-shaped sculpture a “fork” is to employ ambiguous language, not referring to its categories, introducing error.

But what about Zeno, and our stick in water? For our stick in water Aristotle, much like the Epicureans, wants us to examine the stick more carefully, multiple times with multiple senses, to correct the mistake. And, like the Epicureans and Plato too, he surrenders true knowledge of individual objects, saying we can know Categories with certainty, after careful examination, but not specific things.

As for Zeno, there he comes from a different angle, attempting to refute Zeno with pure logic. Aristotle is big on observing Nature, but also on logical principles, especially a priori principles. By these he means logical principles which are self-evidently true and require no knowledge or experience to be proved. For example: The same thing cannot both be and not be at the same time. Think about it for a while, take your time. It’s the case, and not only is it the case but it’s the case for lampreys, and thumbtacks, and hypothetical frictionless spheres, and ideas, and systems of government, and people. Even if you were a brain in a jar that had never had any experience of the world outside the mind, you could identify that a concept cannot both exist and not exist at the same time. Here’s another: “One” and “many” are different. It is nonsense to imagine that a thing could be both singular and plural at the same time. That too you can conclude without any basis in anything.

Now, it is possible to use clever syntax to come up with what seem like counter-examples. What about a doughnut hole: surely it exists and doesn’t exist at the same time, for this doughnut has a non-existence which is its hole, and yet here I am eating this doughnut hole. No, says Aristotle. That apparent contradiction is merely a function of unclear vocabulary giving two things the same label when they are utterly different. Similarly this pomegranate is one and many at the same time. Again, no: it is many seeds, but one pomegranate. Use strict vocabulary, unambiguous terms, and discuss only categories, and you will find that Aristotle’s a priori principles are sound.

Now, it is possible to use clever syntax to come up with what seem like counter-examples. What about a doughnut hole: surely it exists and doesn’t exist at the same time, for this doughnut has a non-existence which is its hole, and yet here I am eating this doughnut hole. No, says Aristotle. That apparent contradiction is merely a function of unclear vocabulary giving two things the same label when they are utterly different. Similarly this pomegranate is one and many at the same time. Again, no: it is many seeds, but one pomegranate. Use strict vocabulary, unambiguous terms, and discuss only categories, and you will find that Aristotle’s a priori principles are sound.

Reasoning from such starts, and using raw logic without recourse to any knowledge of the material world, he then takes on Zeno. You cannot, says Aristotle, have infinite regression. It may seem you can, but an infinite chain is a logical impossibility because it would never end and never start. When you try to think about it, the mind rebels, just as it does when it tries to think of the one and the many being the same, or a thing both being and not being at the same time. Thus, says Aristotle, Zeno’s paradox is proved false because infinite regression is logically false. We can, now, rely on logic, so long as it is careful and methodical, and based on first principles and on comparison of the categories rather than leaping to conclusions directly from sense impressions of individual objects, which are flawed.

Sources of Error: (1) People using vague vocabulary that is unclearly defined and does not refer to anything Real, (2) Fallibility of individual material objects and rushed conclusions based on observations of such objects (note how similar this latter is to Plato).

Criterion of Truth: Knowledge is certain when it is based exclusively on either or a combination of a priori logical principles which are not dependent on anything other than logic to be certain, and on the eternal Categories which exist universally in Nature, and can be known through observation and discussed using a carefully-defined lexicon of philosophical vocabulary.

Zones of the Knowable and Unknowable: We can have true and certain knowledge of logical principles, and of the Categories, i.e. of the eternal structures within Nature that the forms of objects fall into, but we cannot ever have true and certain knowledge of individual objects within the material world.

Thus we have a third path, clearly delineating the arena of certain, eternal knowledge (on the basis of which we may seek eudaimonia) and separating it from the unknowable, which we surrender forever to skepticism. And once again the unknowable is the realm of matter, individual things, the essence which is given structure and comprehensibility by form. Aristotle, like Epicurus, has given up any chance of understanding matter itself, confining the cognizable world to that of form and structure, the macro-level. And he has surrendered knowledge of individuals, of this apple and this lamprey, granting us only the categories. We can still know an enormous amount in Aristotle’s system, enough to build a vast system of knowledge, a library of definitions, a vast network of genus and species names, and an empirical basis for an entire scientific system. Infinite knowledge lies before us on our Aristotelian path, infinite logic chains to follow, infinite categories to investigate, name, compare and discuss. The surrender, like Epicurus’s surrender of the ability to see atoms, feels minor.

“It’s still delusion!” Sartre says. “The surrender is vast! Infinite! Infinitely more vast and fundamental than your daily world imagines!” This outburst has been building up in poor Sartre for some time, which we can tell because since he’s been holding his knees and rocking back-and-forth and flushing, and only barely sociable enough to thank Descartes for that eclair (which is not, in fact, a lightning bolt but is a delicious pastry named “lightning bolt” in French, much to Aristotle’s chagrin). And, at some risk of frightening our innocent interlocutor the Youth (whom I shall advise to have Socrates hold his hand through the next bit) I will let Sartre continue in his own words, an excerpt from his Nausea (note that this particular translation uses existence rather than being):

“So I was in the park just now. The roots of the chestnut tree were sunk in the ground just under my bench. I couldn’t remember it was a root any more. The words had vanished and with them the significance of things, their methods of use, and the feeble points of reference which men have traced on their surface. I was sitting, stooping forward, head bowed, alone in front of this black, knotty mass, entirely beastly, which frightened me. Then I had this vision. It left me breathless. Never, until these last few days, had I understood the meaning of “existence.” I was like the others, like the ones walking along the seashore, all dressed in their spring finery. I said, like them, “The ocean is green; that white speck up there is a seagull,” but I didn’t feel that it existed or that the seagull was an “existing seagull”; usually existence hides itself. It is there, around us, in us, it is us, you can’t say two words without mentioning it, but you can never touch it. When I believed I was thinking about it, I must believe that I was thinking nothing, my head was empty, or there was just one word in my head, the word “to be.” Or else I was thinking . . . how can I explain it? I was thinking of belonging, I was telling myself that the sea belonged to the class of green objects, or that the green was a part of the quality of the sea. Even when I looked at things, I was miles from dreaming that they existed: they looked like scenery to me. I picked them up in my hands, they served me as tools, I foresaw their resistance. But that all happened on the surface. If anyone had asked me what existence was, I would have answered, in good faith, that it was nothing, simply an empty form which was added to external things without changing anything in their nature. And then all of a sudden, there it was, clear as day: existence had suddenly unveiled itself. It had lost the harmless look of an abstract category: it was the very paste of things, this root was kneaded into existence. Or rather the root, the park gates, the bench, the sparse grass, all that had vanished: the diversity of things, their individuality, were only an appearance, a veneer. This veneer had melted, leaving soft, monstrous masses, all in disorder—naked, in a frightful, obscene nakedness.”

“So I was in the park just now. The roots of the chestnut tree were sunk in the ground just under my bench. I couldn’t remember it was a root any more. The words had vanished and with them the significance of things, their methods of use, and the feeble points of reference which men have traced on their surface. I was sitting, stooping forward, head bowed, alone in front of this black, knotty mass, entirely beastly, which frightened me. Then I had this vision. It left me breathless. Never, until these last few days, had I understood the meaning of “existence.” I was like the others, like the ones walking along the seashore, all dressed in their spring finery. I said, like them, “The ocean is green; that white speck up there is a seagull,” but I didn’t feel that it existed or that the seagull was an “existing seagull”; usually existence hides itself. It is there, around us, in us, it is us, you can’t say two words without mentioning it, but you can never touch it. When I believed I was thinking about it, I must believe that I was thinking nothing, my head was empty, or there was just one word in my head, the word “to be.” Or else I was thinking . . . how can I explain it? I was thinking of belonging, I was telling myself that the sea belonged to the class of green objects, or that the green was a part of the quality of the sea. Even when I looked at things, I was miles from dreaming that they existed: they looked like scenery to me. I picked them up in my hands, they served me as tools, I foresaw their resistance. But that all happened on the surface. If anyone had asked me what existence was, I would have answered, in good faith, that it was nothing, simply an empty form which was added to external things without changing anything in their nature. And then all of a sudden, there it was, clear as day: existence had suddenly unveiled itself. It had lost the harmless look of an abstract category: it was the very paste of things, this root was kneaded into existence. Or rather the root, the park gates, the bench, the sparse grass, all that had vanished: the diversity of things, their individuality, were only an appearance, a veneer. This veneer had melted, leaving soft, monstrous masses, all in disorder—naked, in a frightful, obscene nakedness.”

By this point our Youth is very glad to have his hand held, and Descartes is having second thoughts about sharing his eclair with what has evidently turned out to be a lunatic Lovecraftean cultist. But I let Sartre speak here to demonstrate the fact that these surrenders, made in the earliest days of philosophy by system-weavers seeking to escape the web of Zeno and the Stick, are still substantial. Even the most recent modern philosophy returns, from time to time, to these ancient surrenders to unknowability, and some try, like Sartre, to make new inroads toward knowing what the majority of thinkers have given up on. New and, in Sartre’s case, scary inroads. Every system-weaver since Plato may have a Criterion of Truth to be our light in the darkness, our path, our foundation, the circle line for the new philosophical subway system, but the fertile symbiosis between skepticism and dogmatism–the symbiosis which has borne such fruit: Platonic forms, genus and species, atoms, eventually the scientific method itself!–is also still sometimes a hostile symbiosis, and the wild, strong skepticism of Pyrrho still sometimes rears its head to plague Sartre and us, even as we make daily use of soft forms of skepticism like Epicurus’ weak empiricism, and Aristotle’s categories.

By this point our Youth is very glad to have his hand held, and Descartes is having second thoughts about sharing his eclair with what has evidently turned out to be a lunatic Lovecraftean cultist. But I let Sartre speak here to demonstrate the fact that these surrenders, made in the earliest days of philosophy by system-weavers seeking to escape the web of Zeno and the Stick, are still substantial. Even the most recent modern philosophy returns, from time to time, to these ancient surrenders to unknowability, and some try, like Sartre, to make new inroads toward knowing what the majority of thinkers have given up on. New and, in Sartre’s case, scary inroads. Every system-weaver since Plato may have a Criterion of Truth to be our light in the darkness, our path, our foundation, the circle line for the new philosophical subway system, but the fertile symbiosis between skepticism and dogmatism–the symbiosis which has borne such fruit: Platonic forms, genus and species, atoms, eventually the scientific method itself!–is also still sometimes a hostile symbiosis, and the wild, strong skepticism of Pyrrho still sometimes rears its head to plague Sartre and us, even as we make daily use of soft forms of skepticism like Epicurus’ weak empiricism, and Aristotle’s categories.

Of course, many are the centuries between Epicurus and Sartre, and many the new relationships between doubt and dogma, the new Criteria of Truth and new forms of shadowy un-knowledge which will press upon our fragile paths, before we reach the modern world. So we still have much more to explore in further chapters. Good thing Descartes brought plenty of lightning bolts.

After 14 months’ delay, at last you can continue to Part 3: Cicero and Scholasticism.