Venice II: Mask Culture

Often in class I’m lecturing on some aspect of the Renaissance, of Rome, of Florence, and find myself needing to end a sentence with, “…well, except Venice, but Venice was weird.”

Often in class I’m lecturing on some aspect of the Renaissance, of Rome, of Florence, and find myself needing to end a sentence with, “…well, except Venice, but Venice was weird.”

Venice is weird. Very weird. More weird than you think it is, and hopefully a taste of Venetian mask culture will make my point. This is far from a comprehensive treatment, just a little review of tidbits I’ve picked up from the odd lecture here and there, and from visiting many, many mask shops.

Three types of masks roam wild in the shops (and, during Carnival on the streets) in Venice: Festival Masks, everyday masks, and Commedia dell’Arte masks.

Everyday Masks:

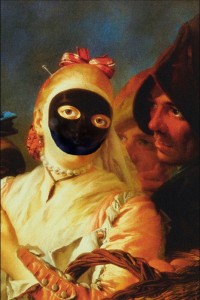

Two wise Carnival goers in decorated Bauta, the most comfortable full-face concealing mask.

Yes, there are such things, or rather there were. Venice was an island capital, ruling a small land empire centered around its lagoon, plus a vast and far-flung naval empire stretching into the distant East. It ruled numerous coastal cities and fortresses in Greece and the Middle East, and had constant dealings with exotic peoples that gave it great wealth, valuable trade secrets, and made it an object of envy and suspicion from the rest of Christendom. Its status at the great central port of the Mediterranean made it a center of everything that had a center: trade, commerce, printing, philosophy, literature, fashion, languages, slavery, silk, paper, heresy, plague, prostitution, perfumes, theater, crime, and especially of exiles, as those who made the rest of the world too hot to hold them ran to the impregnable cosmopolitan island where so many strange peoples mixed refugee statesmen and poets and heretics and deposed kings and fallen tyrants could all hide safe from powerful but landlocked enemies. Even the Medici traditionally picked Venice for their home-in-exile.

Venice was thus a nest of wealth, sin, crime, disease (so much disease!) and, above all, secrets. Trade secrets were the most substantial, Venice’s glass trade in particular. On the island of Murano, carefully segregated so the fires, an inevitability in pre-modern glass works, which periodically consumed the little island could not touch the city’s heart, the Venetians developed numerous new techniques which allowed them alone to produce very expensive marvels. A famous example was their ability to create clear glass, using special quartz pebbles and imported soda ash, in an era when all rivals produced something yellow, brown or green. They also kept innovating, so that every few generations, when outsiders did manage to smuggle out a secret, they gave up the old trade for a new miracle that only Venice could perform. At many far-flung palaces in Sicily, in Spain, in the East, potentates prided themselves on local art, local produce, showcasing their nations’ glory, but still ordered the glass from Venice.

How does this relate to masks? Venice was protective of its secrets, and passed severe laws to prevent their leakage. Glass workers were strictly banned from communication with just about any outsider, and the Venetian nobility as well were for a long time legally forbidden to ever speak to a foreigner. This is a sensible precaution, except when one has to, say, run a government, or participate in trade, or anything nobles actually do. So, the custom developed that nobles would wear masks, and interact with foreigners in an official incognito, even though everyone knew they were nobles. In fact, so codified was this rule, that I went to a talk on a 17th century case of a man who was very severely punished (imprisoned underground, i.e. in a watery pit!) for using a mask to dupe others into thinking he was a noble while cheating at gambling. Venice was not amused.

How does this relate to masks? Venice was protective of its secrets, and passed severe laws to prevent their leakage. Glass workers were strictly banned from communication with just about any outsider, and the Venetian nobility as well were for a long time legally forbidden to ever speak to a foreigner. This is a sensible precaution, except when one has to, say, run a government, or participate in trade, or anything nobles actually do. So, the custom developed that nobles would wear masks, and interact with foreigners in an official incognito, even though everyone knew they were nobles. In fact, so codified was this rule, that I went to a talk on a 17th century case of a man who was very severely punished (imprisoned underground, i.e. in a watery pit!) for using a mask to dupe others into thinking he was a noble while cheating at gambling. Venice was not amused.

Nobles did not have a monopoly on masks, they merely used them in a signature way. Others used them in many aspects of Venetian life, for example prostitution. For example, at one point the Patriarch (i.e. Cardinal) of Venice was concerned for Venice’s morals because the male prostitutes were pulling more business than the female. An ordinance was passed permitting female prostitutes to display themselves nude in the windows of their establishments, to entice customers and encourage general heterosexuality. The male prostitutes retaliated by appearing nude in the windows of their establishments wearing masks. Anything one does while wearing a mask is legally “play” so unless it’s a severe crime (like defacing a Madonna) it isn’t prosecuted.

The everyday masks consist of the Bauta and the Muta (Moretta).

The everyday masks consist of the Bauta and the Muta (Moretta).

The Bauta is an incredibly comfortable and practical full-face mask, of which the upper part fits tight against the forehead, while the lower part is a triangular beak extending several inches forward. This shape makes it easy to breath and speak, and not too difficult to eat and drink, without removing the mask. The top is not rounded to go up to the hairline, but cut off horizontally in the middle of the forehead, to enable it to be worn with a hat. The tricorn is the traditional companion, and combined with a black hood and long cloak, it makes the wearer into an amorphous, beaked cone.

If one wears any other kind of mask for a while (other than a simple half-mask or domino) one rapidly discovers why the Bauta is the shape it is, and that it really is a mask designed to be practical, concealing the face with minimal inconvenience. Originally the Bauta was leather, but later paper took over. It was usually white, and often worn with a long black cloak, black hat, and a black hood, making for a very dramatic starkness. It is the men’s mask.

The lady’s mask (brace yourselves, feminists) is the Moretta, or Muta, or “mute.” It is a small oval-shaped mask which covers only the center of the face, leaving about an inch of skin visible all the way around. It has round eye holes but no nostril holes and no mouth hole, and fits tightly to the face.

The curve of the mask largely conceals the shape of the nose, leaving a sense of complete blankness. The effect of the completely formless, inhuman hole in the middle of the face, with nothing but the staring eyes, is distinctly eerie to behold.

A true Muta also has no straps. Instead, a small button is sewn on the inside of the mask just where the lips are, and the wearer holds the mask on by gripping the button between her teeth. This renders the wearer unable to speak, which, of course, a lady does not need to do. (Grrrrr) So prevalent was the Muta that, in parts of the 17th and 18th centuries, if a lady dressed in the finery of the upper classes went out without one, it was considered a declaration that she was a courtesan. (Because our society still has issues, if you google image search “muta moretta” the first three hits at present are a woman in a muta doing dishes in a modern kitchen in her underwear.)

If shopping for masks in Venice, the Bauta is one of the most practical, usable masks one can choose, and is also easy to find in its authentic white or in a variety of fabulous decorated forms. The Muta is also not hard to find, though most of the modern ones do have straps. A well-made, well-sized Muta is guaranteed to creep people out, though if you are petite you may have trouble finding one that’s small enough, becuase it really needs to leave that inch of visible skin all around it or it doesn’t give off the same feeling of utter negation and inhumanity.

Festival Masks

Festival masks include all the spectacular, elaborate, idiosyncratic constructions of gold and feathers and flowers and animal faces and decoupage that fill the shops and stalls of Venice, and leak out into other tourist centers like Florence and Rome. Such masks are art objects, eye-candy with little-to-no historicity to them. Elaborate showpiece masks were indeed created for the pageants at carnivals, and worn at masked balls, but they were never more than costume pieces, and the truly elaborate ones made today of metallic lacework or covered with sparkling crystals are pure invention. The charming animal masks, I’m sad to say, also have few historical precedents, except that the carnival floats did involve allegorical creatures of every sort you can imagine.

These masks are, when made the traditional way, papier-mâché, made from a special, very strong blue-gray paper which is layered in a plaster mold and held together with a mixture of water and a clear-drying white glue identical to Elmer’s. (No flour is involved, unlike with elementary-school newspaper papier-mâché). An original form for the mask is first made in re-usable oil-based modeling clay. The clay form is covered with plaster to create the mold. Then thousands of paper masks can be made from the mold.

Because the mold is the negative form, and the paper goes inside it, the first layer of paper you put down is the outer surface of the mask, and finer paper is used to make it smooth. This technique means that every subtle texture and wrinkle that was on the clay transfers via the plaster to the paper, so you can create masks with very elaborate three-dimensional modeling, for example fine creases in the forehead and cheeks, quite easily, and reproduce the details with perfection every time. Once complete, the masks are decorated with paint, decoupage and other items, and (when done properly) glazed with the same clear-drying white glue that formed them. The result is reasonably sturdy so long as no strong pressures are put on it, and the plastic coating generated by the dried glue keeps it safe from small amounts of water, ink, food etc., making for a fairly sturdy product.

A large portion of the masks currently for sale are made, not from paper, but from less sturdy mass-produced plastic. These tend to be cheaper, but also break more easily, and when they do break they break completely, where the paper ones just get a bit bent and develop a fissure in the paint instead of cracking entirely. The plastic ones also tend to be mass-decorated and less creative, but many of them are still beautiful. It is also possible to buy blank masks, in both plastic and paper, to take home and decorate – I rarely manage to leave with fewer than 10 blank masks.

As for the cost of masks, on my last visit I observed the following prices:

- Small, blank paint-it-yourself plastic mask, €2-€7

- Small real paper paint-it-yourself blank mask (including Bauta) €8-20

Small, cheaply-decorated plastic mask (including Bauta) €12-25

Small, cheaply-decorated plastic mask (including Bauta) €12-25- More substantial and exciting paint-it-yourself blank mask (like a dragon or a lion) €25-35

- Small, nicely hand decorated real paper mask €20-35

- Large, more elaborate nicely decorated paper mask (including Bauta) €35-40

- Wearable half-mask with feathers or fabric or veils or some such €45-60+

- Large, very elaborate masks: €60 right up into the €200 range

- Cheap quality real leather masks €30+

- Authentic top quality real leather masks including stage-quality Commedia masks €150+

Commedia dell’Arte

The finest, most difficult to find, often the most expensive, and always the ugliest masks, are those of the Italian Comedy, or Commedia dell’Arte. Most famous and popular in the 17th and 18th centuries, it is a great grandchild of Roman comedy, but because so much of the Middle Ages was illiterate, and so little low culture was recorded, we have little knowledge of the two generations in between.

The finest, most difficult to find, often the most expensive, and always the ugliest masks, are those of the Italian Comedy, or Commedia dell’Arte. Most famous and popular in the 17th and 18th centuries, it is a great grandchild of Roman comedy, but because so much of the Middle Ages was illiterate, and so little low culture was recorded, we have little knowledge of the two generations in between.

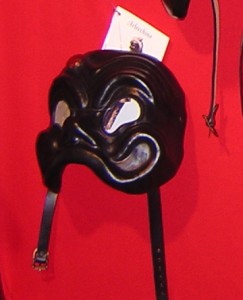

The plays of the Commedia dell’Arte involve a set of stock characters who appear over and over in different scenarios. Each character has a characteristic costume and signature mask, though individual mask designs can vary within set parameters (one wart or three, curly mustache or bushy mustache) etc. They are all silly, distorted and exaggerated, and, from an artistic sense, ugly. This is because the figures are caricature parodies, intended to exaggerate character types the Renaissance and Enlightenment found funny.

Many of the characters of the Commedia are famous and familiar, especially Harlequin, but most people familiar with Harlequin still don’t recognize a Harlequin mask if they see one, because the famous diamond pattern we associate with Harlequin is on the clothing, not the mask. A Harlequin mask is black and pug-nosed with at least one large wart and sometimes a goofy mustache.

Paper Commedia masks abound in Venice and are by far the most economical choice when one wants to collect them all, but the masks that were (and are) used on stage are leather, not paper, and it is still possible to find leather masks in Venice, and elsewhere. These masks are flexible and much more durable and comfortable. They are also much more difficult to make, and consequently expensive. Not only is leather a more expensive material than paper, but the process is more labor-intensive and requires more skill.

This is largely because the mold is backwards. In making a paper mask, the mold is negative, and the soft paper goes inside. In a leather mask the wooden mold is positive, and the leather is stretched over the outside. This means that for the paper, fine details can be sculpted into the original and included in the mold, so every crease and wrinkle comes across perfectly in every paper copy. With the leather masks, the outer surface of the leather is smooth, so fine details like wrinkles have to be tooled in by hand on every individual mask, making each product more unique, but also requiring a much more practiced hand.

For this reason there is an enormous difference between low- and high-quality leather masks, in price and in detail. Low quality leather masks, which are generally still quite awesome, usually lack any three-dimensional surface details, since they were made by simply stretching the leather over a mold without further tooling. They also tend to have a rougher, more organic texture. It is possible to find nice leather masks of this type for as little as thirty or forty euros. On the other hand, the stage-quality, fully tooled ones are extremely smooth and shiny, and tend to start at 150 euros and go up and up and up.

Just set side-by-side a leather stage-quality Commedia mask is generally much less beautiful than carnival masks which cost less than half as much, but to me it’s worth it. The big difference comes when you put one on.

Donning a beautiful mask makes you look awesome and somewhat mysterious and exotic, but the masks themselves are independent art, and often look just as fantastic on the shelf or wall as on a person. A Commedia mask, though, comes to life when it’s on a human face, and suddenly a strange, lively new creature is standing in the room. I’ve never seen anything quite like the burst of delight that hits a friend’s face when she watches another friend pop on a Pulcinella or a Pantalone, or the absolute transformation of body language of the wearer as he sees himself in the mirror and feels like someone else. It isn’t putting on a mask, it’s putting on a person, and the exaggerated eyebrows and ridiculous noses have been perfected over centuries to create a delightful, entertaining new life-form, the creature of the Comedy. At home, where my many, many, too many Venetian masks range across the shelves, it’s the Carnival masks that always make first-time visitors ooh and aah, but when the moment comes to try one on I always reach first for the Commedia.

As for the characters themselves, I’ll review them in another post.

Meanwhile a quick survey:

I’m taking a jaunt to the US this month, and want to bring back some fun goodies for my Italian friends. What non-perishable, portable, only-available-in-America food can you think of which would be a good present to bring back? Just don’t say Twinkies – they’re so (in)famous I’ve already had a request!