The Shape of Rome

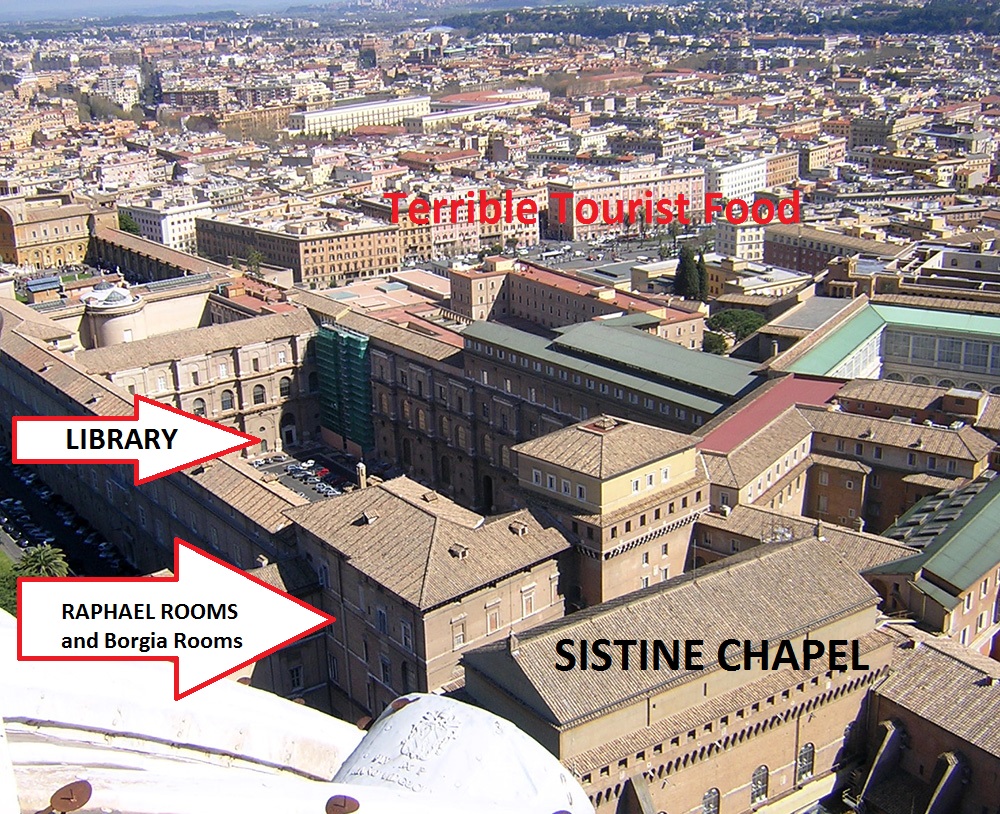

The new Mayor of the city of Rome, Ignazio Marino, just announced his intention to destroy one of the city’s central roads, the Via dei Fori Imperiali, and turn the area around the old Roman Forum into the world’s largest archaeological park. Reactions have ranged from commuters’ groans to declarations from classicists that this single act proves the nobility of the human species.

The new Mayor of the city of Rome, Ignazio Marino, just announced his intention to destroy one of the city’s central roads, the Via dei Fori Imperiali, and turn the area around the old Roman Forum into the world’s largest archaeological park. Reactions have ranged from commuters’ groans to declarations from classicists that this single act proves the nobility of the human species.

This curious range of reactions seems the perfect moment for me to discuss something I have intended to talk about for some time: the shape of the City of Rome itself. We all know the long, rich history of the Roman people, and the city’s importance as the center of an empire, and thereafter as the center of the memory of that empire, whose echo, long after its end, still so defines Western concepts of power, authority and peace. What I intend to discuss instead is the geographic city, and how its shape and layers grew gradually and constantly, shaped by famous events, but also by the centuries you won’t hear much about in a traditional history of the city. The different parts of Rome’s past left their fingerprints on the city’s shape in far more direct ways than one tends to realize, even from visiting and walking through the city. Rome’s past shows not only in her monuments and ruins, but in the very layout of the streets themselves. Going age by age, I will attempt to show how the city’s history and structure are one and the same, and how this real ancient city shows her past in a far more organic and structural way than what we tend invent when we concoct fictitious ancient capitals to populate fantasy worlds or imagined futures. (As a bonus to anyone who’s been to Rome, this will also tell you why it’s a particularly physically grueling city to visit, compared to, say, Florence or Paris.)

Sigmund Freud had a phobia of Rome. You can see it in his letters, and the many times he uses Rome as a simile or metaphor for psychological issues, both broadly and his own. He fretted for decades before finally making the visit. Part of it was a cultural inferiority complex. Europe’s never-fading memory of the greatness of the Roman empire was intentionally magnified in the Renaissance by Italian humanists who set out to convince the world that Roman culture was the best culture, and that the only way to achieve true greatness was to slavishly imitate the noble Romans. Italians did this as a power play to try to overcome the political weakness of Italy, but as a result, in the 19th and 18th centuries, many intellectuals in many nations were brought up in a mindset of constantly measuring their own nations only by how far they fell short of the imagined perfection of Rome. Freud was one of many young intellectuals in Germany, Poland, and other parts of Europe who were terribly intimidated by the Idea of Rome, and the sense that their own nations could never approach its greatness.

Sigmund Freud had a phobia of Rome. You can see it in his letters, and the many times he uses Rome as a simile or metaphor for psychological issues, both broadly and his own. He fretted for decades before finally making the visit. Part of it was a cultural inferiority complex. Europe’s never-fading memory of the greatness of the Roman empire was intentionally magnified in the Renaissance by Italian humanists who set out to convince the world that Roman culture was the best culture, and that the only way to achieve true greatness was to slavishly imitate the noble Romans. Italians did this as a power play to try to overcome the political weakness of Italy, but as a result, in the 19th and 18th centuries, many intellectuals in many nations were brought up in a mindset of constantly measuring their own nations only by how far they fell short of the imagined perfection of Rome. Freud was one of many young intellectuals in Germany, Poland, and other parts of Europe who were terribly intimidated by the Idea of Rome, and the sense that their own nations could never approach its greatness.

But Freud had a second fear: a fear of Rome’s layers. In formal treatises, he compared the psyche to an ancient city, with many layers of architecture built one on top of another, each replacing the last, but with the old structures still present underneath. In private writings he phrased this more personally, that he was terrified of ever visiting Rome because he was terrified of the idea of all the layers and layers and layers of destroyed structures hidden under the surface, at the same time present and absent, visible and invisible. He was, in a very deep way, absolutely right. Rome is a mass of layers, the physical form of different time periods still present in the walls and streets, and when you study them enough to know what you are really looking at, they reach back so staggeringly far, through so many lifetimes, that if you let yourself think seriously about them it is easy to be overwhelmed by the enormity of it all.

I will begin by discussing a single building as an example, and then the broader structure of the city.

The Basilica of San Clemente:

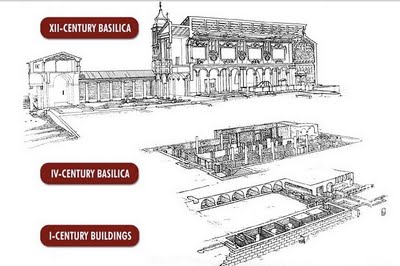

San Clemente is a modestly-sized church a couple blocks East of the Colosseum, one of many hundreds of churches in Rome, and, in my mind, the most Roman. It was built in honor of Pope Clement I (d. 99 AD), an important early cleric who traveled East and returned, making him one of the most important linking figures between the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox worlds. One enters the church from a plain, hot street populated by closed doors plus an antique shop and a mediocre pizzeria. Outside the door is a beggar disguised as someone who works for the Church trying to extort money from tourists by convincing them that they have to pay him to enter. Within, a lovely, lofty church with marble columns, frescoed chapels, a beautiful stone floor, stunning gold mosaics in the nave, and a gilded wood ceiling. It is populated by milling tourists, and perhaps a couple of the Irish Dominicans who are now its custodians. It is reasonably impressive, but when we pause and look more closely, we realize the decoration is not as simple as it seems. Nothing matches, for a simple reason: No two pieces of this church are from the same time.

The basic structure of the church, the actual edifice, is from the twelfth century. But nothing else.

Look at the columns first: beautiful colored marble columns with delightful translucent swirls of stone. But they don’t match: they’re different colors, even different heights, and have non-matching capitals and different size bases to try to make them fit. These columns weren’t made for this building, they are looted columns, carried off from Roman buildings all around the city and repurposed for this Church. These columns, therefore, were cut about 1,000 years before the construction of this church.

The floor too is Roman mosaic tile, inlaid with pieces of porphyry and serpentine, materials unachievable after the empire’s fall. If they are here, they were carried here after the 12th-century Church was built and re-used.

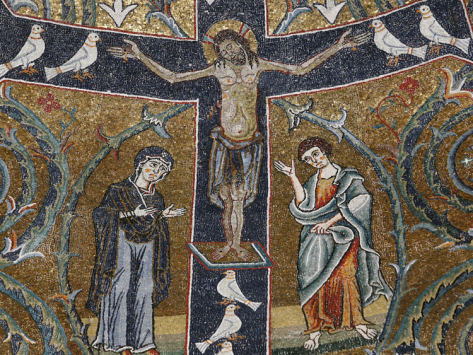

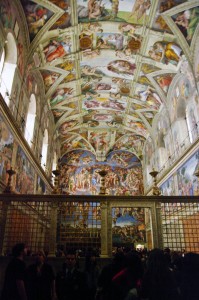

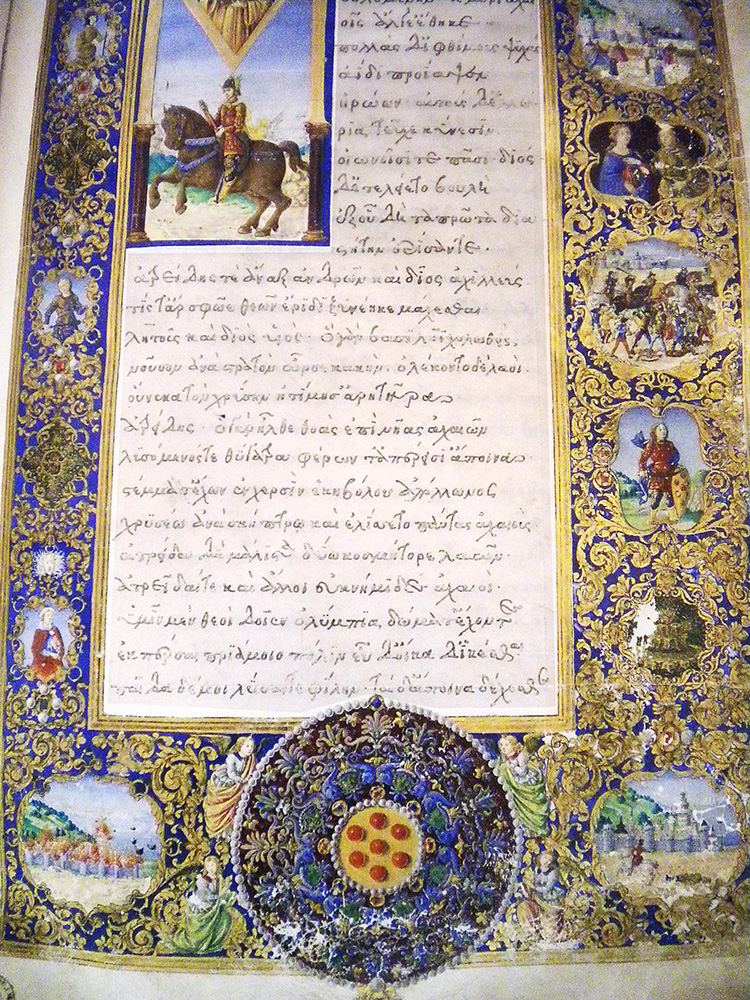

What else? There is the stunning mosaic. It looks like nothing else we’ve seen in Rome, and with good reason. It looks Russian or byzantine, a totally different style. Foreign artists must have come in to create this, not in a Roman style of decoration at all but one more Eastern. Our Eastern Church devotees of Saint Clement have been here.

We turn around next, and spot a lovely side chapel with frescoes of a saint’s life, in a familiar Renaissance style. We might have seen this on the walls of Florence, produced in the late 1400s or earlier 1500s, and can immediately start playing Spot the Saint.

But next we make the mistake of looking up, and realize that this massive hanging gilded wood ceiling is entirely wrong, with overflowing ribbons and a dominant central painting of a much more flowy, ornamented, emotional, voluptuous Baroque style than everything else. The artist who painted those modest Spot the Saint frescoes would never drown a scene in little cherubs and clouds like this, nor would that ceiling ever have been near these Roman columns.

The upper walls too have Baroque decoration. Even an untrained eye is aware something is wrong. The practiced eye can tell instantly that the ceiling must be late sixteenth century at the very earliest and is more likely seventeenth or eighteenth, three hundred years newer than the Spot the Saint frescoes, which were two hundred years after the mosaics, which are two hundred years after the church was built using stolen Roman materials that were already 1,000 years old. Freud, exploring the church with us, has vertigo.

Next we look down.

What’s this? What are these arches in the wall next to the floor? Why would there be arches there? It makes no sense. Even in a building that used secondary supporting arches in the brickwork there would be a reason for it, a window above, a junction, and they would end at floor level. Our architecture-sense is tingling.

So we go down stairs…

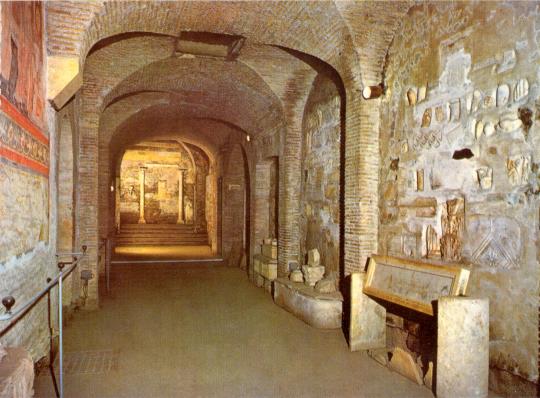

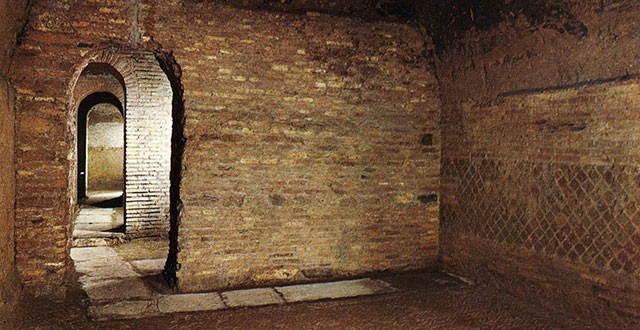

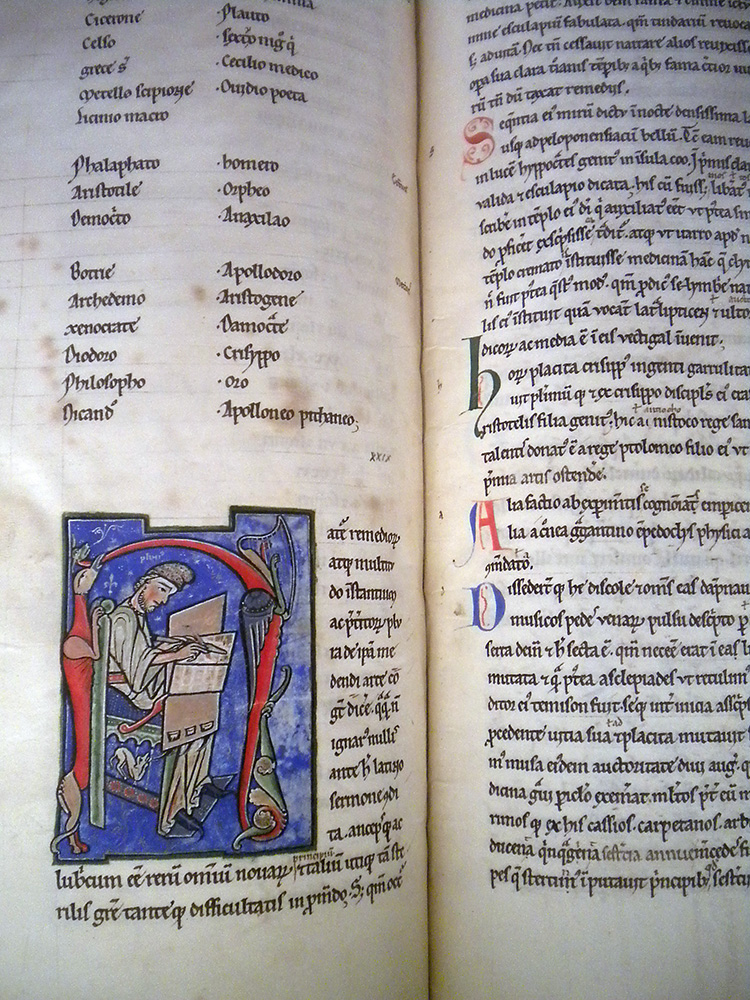

Welcome to the 4th century Roman basilica which the 12th century upper church was built on top of. Here we see characteristic dense, flat Roman bricks, and late classical curved-corner ceiling structures laying out what used to be an early Christian church. This church was 800 years old when it was buried to build the larger one above it. The walls are studded with shards of Roman sculpture, uncovered during the excavations, bits of broken tombs, halves of portrait faces and the middle of an Apollo, and a slab with a Roman pagan funerary inscription on one side which was re-used and has an early Christian inscription on the other side, in much cruder lettering.

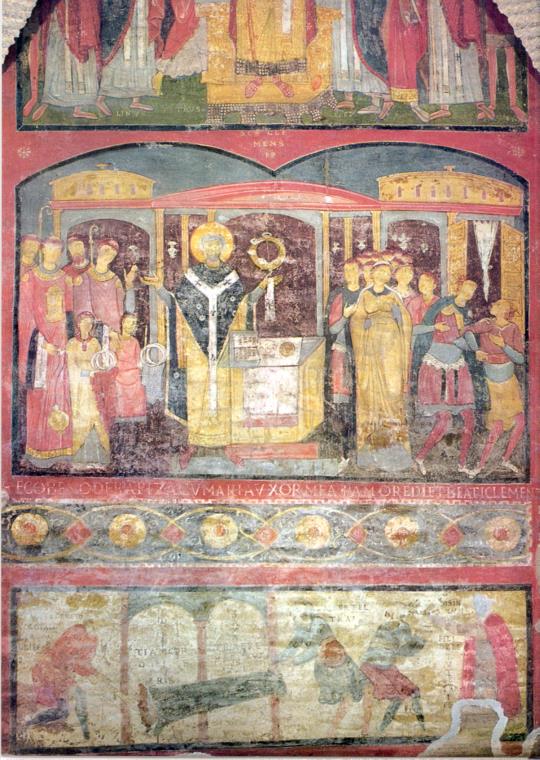

And here too there are frescoes. Legend has that Saint Clement’s remains were carried from the East back to Rome in 869 AD, and this lower church is the place they would have been carried to, as we see now in a fresco depicting the scene, painted probably shortly thereafter.

Other 9th century frescoes (300 years older than the church above) show the lives of other now-obscure figures who were important in the 800s. One features a portrait of an early pope (Leo IV), the only known image of this largely-forgotten figure. Another features Christ freeing Adam from Limbo, and to their left a man in a very Eastern-looking hat, another relic of the importance of this church as a center for Rome’s contact with the east.

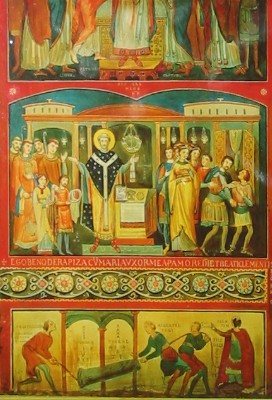

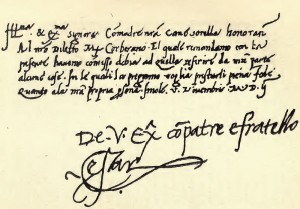

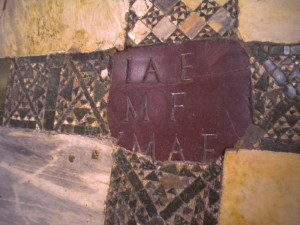

Another wonderful fresco, of the life of a popular hermit, features a story in which a pagan demands that his servants carry the saint out of his house, but he goes mad and believes a column is the saint, and flogs and curses his slaves as he forces them to carry the column. In this fresco we find inscriptions in Latin, but also a phrase coming out of the man’s mouth (a very crude one cursing his slaves as bastards and sons of prostitutes) which is the oldest known inscription in a language identifiable as, not Latin, but Italian. The Italian language has come to exist between the construction of this church and the construction of the one above. (The inscription is at the bottom in the white area above the column, hard to make out.)

You can see it better in this reconstruction:

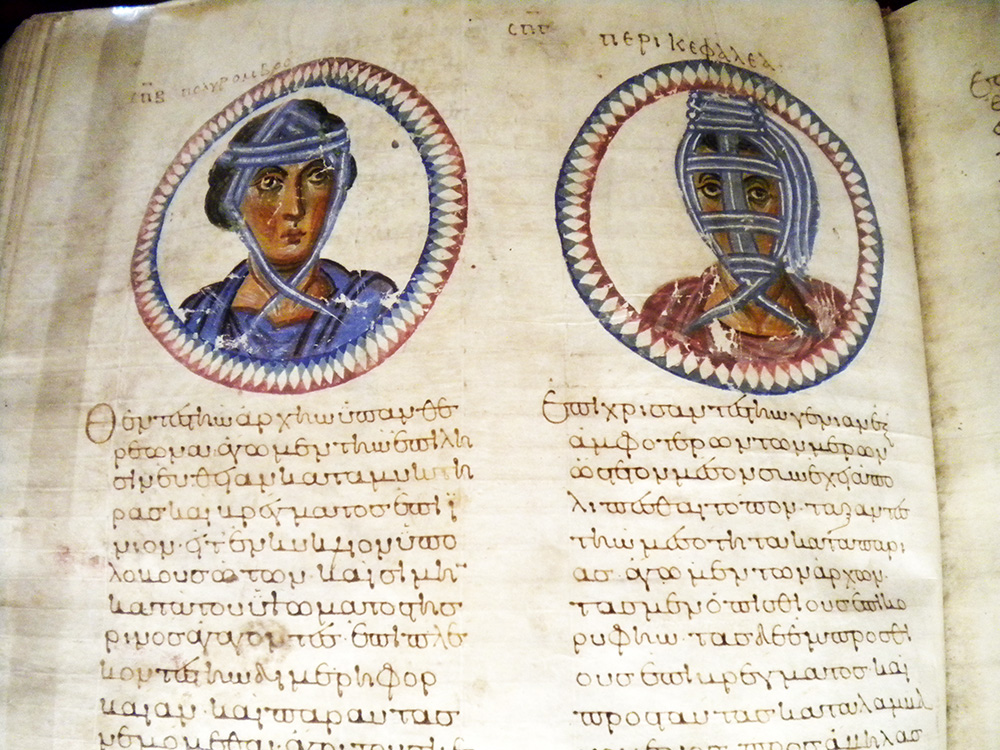

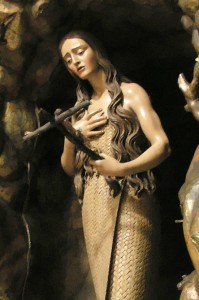

One more fresco is worth visiting: the Madonna of the funny-looking hat.

When archaeologists opened up the under layer, they found a Madonna, probably 8th century, which then decayed before their eyes (horror!) due to exposure to the air. Underneath they found another Madonna (delight!) wearing this extremely strange hat. They looked more closely: the Christ child in her lap is not original, but was painted on after the Madonna. This is not a Madonna at all, it is a portrait, and that hat belongs to none other than the Byzantine Empress Theodora. Someone painted a portrait of the empress here (who used to be a prostitute, I might add), then someone else redid her as a Madonna, then, a century or two later, someone else painted over that Madonna with another Madonna, now lost, who presumably had a more reasonable hat.

Wandering a bit we find more modern additions, post-excavation. One of the most beloved 20th century heads of the Vatican Library has been buried here, just below the now-restored old altar of the lower church. And the tomb of St. Cyril [or possiby it contains Cyril and his brother Methodius – there is debate] is here. They are the creators of the Glagolitic alphabet (ancestor of the Cyrillic), surrounded by plaques and donations and tokens of thanksgiving from many Slavic countries who use that alphabet. Below is a modern mosaic, thanking them for their work:

And nearby there are stairs down… Freud needs to stop and breathe into a paper bag.

There are stairs down because this is not the bottom layer, not yet. The 4th century church was built on top of something else. We descend another floor and find ourselves in older, pre-Christian Roman brickwork. We find high vaults, frescoed with simple colorful decoration, as was popular in villas and public buildings. Hallways and rooms extend off, a large, complex building. Very complex. Experts on Roman building layout can tell us this was once a fine Roman villa of the first century AD. In that period it had sprawling rooms, a courtyard, storerooms… but its foundations aren’t quite the right shape. If we look at the walls, the layout, it seems that before the villa there was an industrial building, the Mint of the Roman Republic (you heard me, Republic! Before the Empire!), but it was destroyed by a fire (the Great Fire of 64 AD) and then rebuilt as a Roman villa. Before it was a church… before it was another church.

Except… there are tunnels. There are narrow, meandering tunnels twining out from the walls of this villa, leading in strange, unpredictable directions, and far too tight to be proper Roman architecture. This villa was on a slope, and some of these rooms are dug into the rocky slope so they would have been underground even when it was a residence. Romans didn’t do that.

Houston, we have a labyrinth, a genuine, intentional underground labyrinth, and with a bit more digging we find out why. This was a Mithraeum, a secret cult site of the Mithraic mystery cult, which worshipped the resurrection god Mithras. Here initiates dwelled in dormitories for their years of apprenticeship, waiting their turn to enter the clandestine curved vault, sprawl on its stone couches, and participate in the cult orgy in which they take hallucinogens, play mind-bending music, and ritually sacrifice a bull and drink its blood in order to achieve resurrection.

We wander still farther, daring the labyrinth, much of which has not yet been excavated, and come upon another room in which we hear the bubbling of a spring. A natural spring, miraculously bubbling up from nowhere in the depths of Rome. Very probably a sacred spring.

While Freud sits down to put his head between his legs for a while (on a 1st century AD built-in bench, I should add) we can finally piece this muddle of contradictory and mismatched objects together into a probable chronology:

Once upon a time there was a natural spring bubbling up at this spot in what was then the grassy outskirts of early Rome. It is reasonable to guess that a modest cult site might have sprung up around this spring, honoring its nymph or some such, as was quite common. In time, the city expanded and this once-abandoned area became desirable for industrial use as the Republic gained an empire. The Republic’s Mint was built here, making use of the convenient ice cold water, and likely continuing to honor its associated spirit. Decades pass, a century, two, Rome expands still further, and chaos raises an Emperor. After the Great Fire of 64 AD, it becomes convenient to move the Mint out of what is now a desirable central district of the expanding city, so the site is purchased by a wealthy Roman who builds his house here. Decades pass and the builder, or his son, is converted to the exciting cult of this new god Mithras who promises his followers, not the gray mists of Hades, but resurrection and eternity. Since he is wealthy, he converts his home to the use of the cult, and digs tunnels and creates the underground Mithraeum. For a generation or two this villa hosts the cult, but then Constantine comes to power and a new cult promising an even more inclusive form of salvation comes into vogue. The villa, which is now three hundred years old, is buried, a convenient architectural choice since the ground level of the city has risen several times due to regular Tiber floods, so the old house was in a low spot. A new church is built on top, and serves the Roman Christians of the local community for a few generations. The fall of Rome is usually marked at the first sack by they Visigoths in 410 or the sack by the Vandals in 455, but the conquerors are also Christian so the church stands and still serves the neighborhood, though its population is much smaller. Now the main Emperor moves to the East, and in the 500s, when the church is about 200 years old, someone paints a portrait of the empress on the wall, then a generation later someone else decides a Madonna is more appropriate, and puts a baby in her lap. Two or three more generations go by and Cyril and Methodius bring the bones of Clement from the East, and they are buried here, a great day for the neighborhood! Commemorated with more frescoes.

Once upon a time there was a natural spring bubbling up at this spot in what was then the grassy outskirts of early Rome. It is reasonable to guess that a modest cult site might have sprung up around this spring, honoring its nymph or some such, as was quite common. In time, the city expanded and this once-abandoned area became desirable for industrial use as the Republic gained an empire. The Republic’s Mint was built here, making use of the convenient ice cold water, and likely continuing to honor its associated spirit. Decades pass, a century, two, Rome expands still further, and chaos raises an Emperor. After the Great Fire of 64 AD, it becomes convenient to move the Mint out of what is now a desirable central district of the expanding city, so the site is purchased by a wealthy Roman who builds his house here. Decades pass and the builder, or his son, is converted to the exciting cult of this new god Mithras who promises his followers, not the gray mists of Hades, but resurrection and eternity. Since he is wealthy, he converts his home to the use of the cult, and digs tunnels and creates the underground Mithraeum. For a generation or two this villa hosts the cult, but then Constantine comes to power and a new cult promising an even more inclusive form of salvation comes into vogue. The villa, which is now three hundred years old, is buried, a convenient architectural choice since the ground level of the city has risen several times due to regular Tiber floods, so the old house was in a low spot. A new church is built on top, and serves the Roman Christians of the local community for a few generations. The fall of Rome is usually marked at the first sack by they Visigoths in 410 or the sack by the Vandals in 455, but the conquerors are also Christian so the church stands and still serves the neighborhood, though its population is much smaller. Now the main Emperor moves to the East, and in the 500s, when the church is about 200 years old, someone paints a portrait of the empress on the wall, then a generation later someone else decides a Madonna is more appropriate, and puts a baby in her lap. Two or three more generations go by and Cyril and Methodius bring the bones of Clement from the East, and they are buried here, a great day for the neighborhood! Commemorated with more frescoes.

Another century, two, we are well into the Middle Ages, and this old Roman building is old-fashioned and very low since the ground level has risen further. The local community, and devotees of St. Clement, decide to build a new church. They loot columns and flooring from other Roman sites, and bury the old church, producing the 12th century structure above, but using the walls of the older one as the foundation, so the arches still show in the walls. The new church is very plain, but is soon decorated using mosaics provided by Eastern artists who come to visit Clement and Cyril. After a few generations the Renaissance begins, and we call in a fashionable Florentine-style artist to fresco one chapel. A few centuries later Pope Clement VIII comes to power and decides to spiff up San Clemente, initiating the internal redecoration which will end with the ornate baroque ceiling.

Another century, two, we are well into the Middle Ages, and this old Roman building is old-fashioned and very low since the ground level has risen further. The local community, and devotees of St. Clement, decide to build a new church. They loot columns and flooring from other Roman sites, and bury the old church, producing the 12th century structure above, but using the walls of the older one as the foundation, so the arches still show in the walls. The new church is very plain, but is soon decorated using mosaics provided by Eastern artists who come to visit Clement and Cyril. After a few generations the Renaissance begins, and we call in a fashionable Florentine-style artist to fresco one chapel. A few centuries later Pope Clement VIII comes to power and decides to spiff up San Clemente, initiating the internal redecoration which will end with the ornate baroque ceiling.

Oh, and somewhere in there someone slapped on a courtyard on the outside in a Neoclassical style, because it became vogue for buildings to look classical, so we may as well add a faux-classical facade onto this medieval building which we no longer remember has a real classical building hidden underneath. Not long after the Baroque redecoration is begun, the nineteenth-century interest in archaeology notices those arches in the walls, and starts digging, re-exposing the lower layers. Devotees of St. Cyril and lovers of history, like the head of the Vatican Library, begin to flock to San Clemente as an example of Rome’s long and layered history, and so it gains more layers in the 20th century as donations and burials are added to it. Every century from the Republican Roman construction of the Mint to the 20th century tombs is physically present, actually physically represented by an artifact which is still part of this building which has been being built and rebuilt for over 2,000 years. Not a single century passed in which this spot was not being used and transformed, and every transformation is still here. And all that time, from the first sacred spring, to the Mithraism, to today’s Irish Dominicans, this spot has been sacred.

Oh, and somewhere in there someone slapped on a courtyard on the outside in a Neoclassical style, because it became vogue for buildings to look classical, so we may as well add a faux-classical facade onto this medieval building which we no longer remember has a real classical building hidden underneath. Not long after the Baroque redecoration is begun, the nineteenth-century interest in archaeology notices those arches in the walls, and starts digging, re-exposing the lower layers. Devotees of St. Cyril and lovers of history, like the head of the Vatican Library, begin to flock to San Clemente as an example of Rome’s long and layered history, and so it gains more layers in the 20th century as donations and burials are added to it. Every century from the Republican Roman construction of the Mint to the 20th century tombs is physically present, actually physically represented by an artifact which is still part of this building which has been being built and rebuilt for over 2,000 years. Not a single century passed in which this spot was not being used and transformed, and every transformation is still here. And all that time, from the first sacred spring, to the Mithraism, to today’s Irish Dominicans, this spot has been sacred.

This is Freud’s metaphor for the psyche: structure after structure built in the same space, superimposing new functions over the old ones, never really losing anything.

This is Rome.

San Clemente is exceptional in that it has been largely excavated and is accessible, but every single building in Rome is like this, built on medieval foundations which are built on classical ones. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve gone into a random pizzeria and found a Renaissance fresco, or a medieval beam, or Roman marble. I’ve gone into a cafe restroom and discovered the back wall was curved because this was built on the foundations of Pompey’s theater (where Caesar was assassinated). I’ve gone into churches to discover their restrooms used to be part of different churches. Friends have this experience too. During my Fulbright year in Italy I had a colleague who was studying Roman altars, half of which you could only get at by ringing the bell of strangers’ apartments and saying: “Hello! I’m an archaeologist, and according to this list there’s a Roman sacrificial altar here?” to which the standard response is, “Oh, yes, come on in, it’s in the basement next to the washing machine.” I have another friend who thinks he’s found a lost chapel frescoed by a major Renaissance artist hidden in an elevator shaft. Another friend once told me of a pizza place with a trap door down to not-yet-tallied catacombs. I believe it.

As with San Clemente, so for Rome: layers on layers on layers:

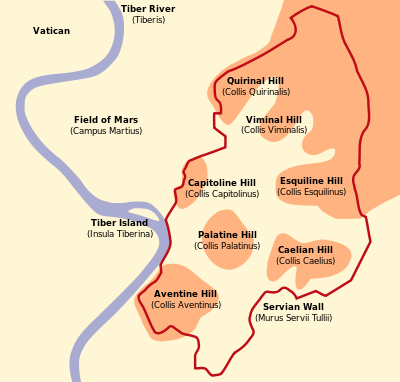

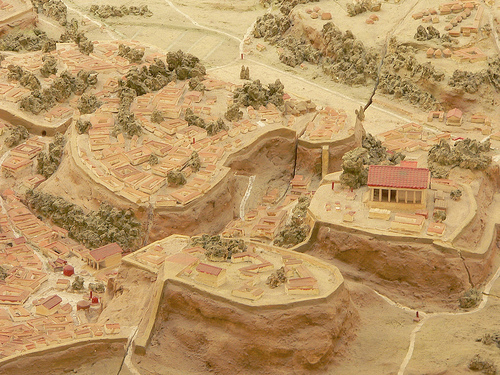

If San Clemente’s narrative starts with a sacred spring and the Roman Mint, Rome’s narrative starts with scared people on a hill.

Welcome to the archaic period. You are a settler. Your goals are securing enough food to stay alive, and avoiding deadly threats. The major threats are (A) lions, (B) wolves, (C) wild boar, (D) other humans, who travel in raiding parties, killing and taking. You are looking for a safe, defensible spot to settle down. You find one. The Tiber river, which floods regularly producing a fertile tidal basin rich with crops and game, takes a bend and has a small island in it. At that same spot there are several extremely steep, rocky hills, almost like mesas, with practically cliff-like faces. In such a place you can live on top of the hill but hunt, farm, and gather on the fertile stretch below. And you can even sail up and down the river, making trade and travel easy. Perfect.

The very first settlement at Rome, in the archaic period, was a small settlement on the Capitoline hill, one of the smallest hills but closest to the river. (Are you, perchance, from a country? With a government that meets in a “capitol” building? If so, your “capitol” is named after the Capitoline hill, because that’s how frikkin’ important this hill is!) The valleys around are used mainly for farming, but also for burials, and the first tombs are very simple ones, just a hole with dirt, or sometimes a ceramic tile lid. The buildings in this era are brick decorated with terra cotta. Eventually the first major temple is built on the Capitoline hill, with a stone foundation but still terra cotta decoration, and is dedicated to Jupiter. Its foundations remain, and you can see them, in situ, in the Capitoline museum which will be built on the same spot a few millenia later.

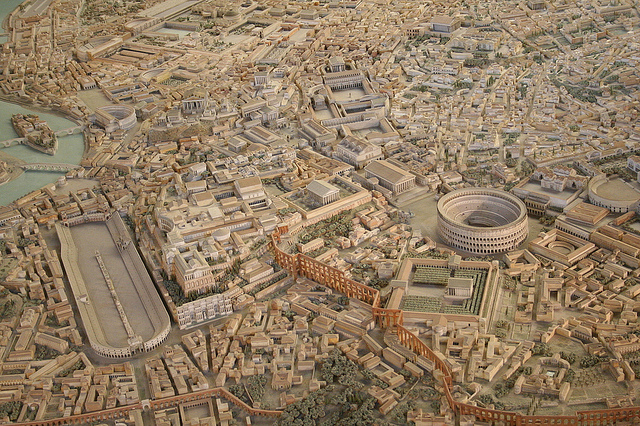

This hill turns out to be a great place to live, and the population thrives. In time the hill is too crowded. People spread to the neighboring hills, and start building in the little valley in between. As the population booms and spreads to cover all seven hills, the space between the first few becomes the desirable downtown, the most important commercial center, where the best shops and markets are. This is the Forum, and here more temples and law courts and the Senate House are built.

In time, defensive walls go up around the area around the hills, to make a greater chunk of land defensible. In time, the walls are too constrained, so another set goes up around them.

As the population booms and Rome becomes a serious city, serious enough to start thinking about conquering her neighbors and maybe having a war with someone (Carthage anyone?), this area is now the super desirable downtown. The commercial centers migrate outward to give way to monuments and temples, the Mint is built out on a grassy spot past where there is not yet a Colosseum, and the hills near the Forum become reserved for sacred spaces, state buildings, and the houses of the super rich. On one, the Palatine hill, a certain Octavian of the Julii builds his house, and when Caesar is assassinated and the first and second triumvirates result in an Emperor, it becomes the imperial palace. (Does your capital contain a palace? If so it’s named after the Palatine hill, because Augustus was so powerful that all rulers’ grand houses are forever named after his house).

Rome again spills over her walls and builds even farther out. The great fire of 64 AD destroys many districts, but she rebuilds quickly, and what was the Mint is replaced by a villa which soon becomes a Mithraeum. Rome reaches its imperial heights, a sprawling city of a million souls, and the seven hills that were once defensive are now sparkling pillars of all-marble high-class real estate, and also very tiring to climb.

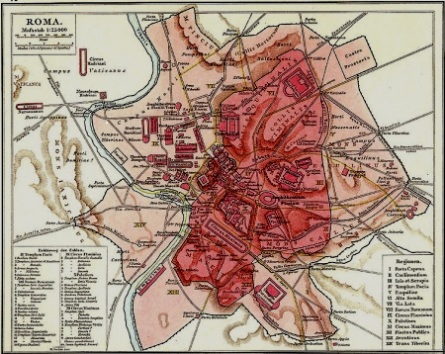

With Constantine, Christianity now becomes a centerpiece of Roman life, and of the city’s architecture. Major Christian sites are built: St. Peter’s, St. John Lateran, St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, etc. These sites become pilgrimage centers, and economic centers. They are scattered in far corners all around Rome, but all the sites have something in common: they are in corners. The major Christian centers of Rome are all on its periphery, not in the center. There are two reasons for this.

First, and simplest, the center of Rome was, by this time, already full. Sometimes you could find an old villa that used to be a mint to build a small church on, but the center was full of mid-sized temples, which could be rededicated but not replaced, and huge imperial function spaces and government buildings, plus valuable real estate. If you want to build a big new temple to a big new God, you need to do it in the not-yet-developed areas around the city’s edge.

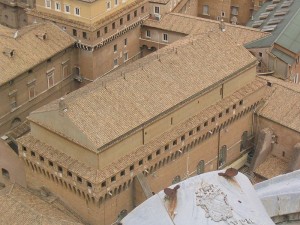

Second, many of these sites were built on tombs, like St. Peter’s, built across the river in the cheap land no one wanted. Roman law banned burying the dead within the city limits, because disturbing a tomb could bring the wrath of the dead upon the city, but if you build immovable tombs in the middle of your city it makes city redevelopment impossible, so they have to be outside. This is the origin of the necropolis or “city of the dead”, the cluster of tombs right outside the gates of a Roman city, where the residents bury their dead. Some major Roman Roads, like the Via Appia, are still lined with rows of tombs stretching along the street for miles out from where the city limits used to be defined. Thus early Christian martyrs were buried outside the city, and their cult sites developed at the edges of the city. The land which became the Vatican, for example, was across the river, full of wild beasts and scary Etruscan tribesmen in archaic Rome, then was used for a necropolis in Imperial Rome, had enough empty cheap land to build a big circus (where much of the throwing of Christians to the lions happened, since only in such cheap real estate could you build a stadium big enough to hold the huge audiences who wanted to come see lions eat Christians), and finally Constantine demolished the circus and necropolis to build St. Peter’s to honor St. Peter who had been martyred in that circus and buried in the necropolis in secret 300 years before (when San Clemente was still a Mint). St. Peter’s, and the other Christian sites, bring new importance to Rome’s outskirts. We now have a bull’s-eye-shaped city, in which imperial government Rome is the center, and Christian Rome is a ring around the outside, with rings of thriving, happy commercial and residential districts in between.

410 and 455 AD: outsiders arrive and plunder the city. Many thousands are killed, and the beautiful center of Rome is ransacked, temples toppled, looted, burned. In the Forum, the raiders throw chains around the columns of one of my favorite layered Roman buildings, the temple of Antoninus and Faustina. The Visigoths try to pull the columns down with their chains, and fail, but slice gouges deep into the stone which you can still see today. To re-check time, the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina was built in 141 AD, when San Clemente was a villa with an active Mithraeum in it. When it received these scars in the Visigothic raid, the Mithraeum had been buried, and the church built on top was just starting to be decorated. And underneath the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina we have found archaic grave sites which were 1,000 years old when the temple was built 2,000 years ago–the people buried in those graves very likely drank water from the spring that still burbles up under San Clemente. As for the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina, a few centuries after its near-miss, the temple will be rededicated as the major Roman church of San Lorenzo, due to a legend that it was on these temple steps that Saint Lawrence was sentenced to be grilled alive. And not far from it, the Lapis Niger was excavated which contains a language which has not yet become Latin, much as San Clemente’s frescoes preserve one which is becoming Italian. One language evolved into another, then into a third, but this spot was still being used, just like today.

Rome was sacked, but afterwards Rome was still there. The Goths didn’t just take everything and leave – the Ostragoths who followed the Visigoths decided to become the new Roman Emperors and rule Italy. The surviving Roman patrician families started working for the new Gothic king, but still had a Senate, taxes, processions, traffic cops, and did all the early Medieval equivalents of keeping the trains running on time. A century later, in the 540s, the Plague of Justinian hits and Rome loses another huge hunk of its population. But it still ticks on, and there is still a Senate, and a people of Rome.

So what was different? From a city-planning sense, the key is that the population was much smaller. In a sprawling metropolis designed to hold a million people, we now had maybe twenty thousand. Thus, as always happens when a city’s population shrinks, real estate was abandoned. But instead of abandoning the outskirts, people abandoned the middle. Rome was important mostly as a Christian center now, with the pope, and pilgrims coming to major temples, so they occupied the edges, and that’s where the money was. Rome becomes a hollow city, a doughnut, with an abandoned center surrounded by a populated ring. We have reached Medieval Rome. The city population lives mainly over by the Vatican, in the once empty district across the river, and a few other Christian sites around the edge. The middle of the city has been abandoned so long that the Tiber has buried the ruins, and people graze sheep in what used to be the Forum. The old buildings are now little more than quarries, big piles of stone and brick which we can steal from if, for example, we happen to need some nice columns to build a new church on top of this old church of San Clemente.

Enter the Renaissance, Petrarch, and humanism. Petrarch writes of the glory that was Rome, and convinces Italy that, if they can reconstruct that, they can be great again, just as when they conquered the Goths and Germans. Popes and lords become hungry for the symbols of power which Rome once was. Petrarch reads his Cicero and his Sallust, and visits the empty center of the city. This is the Capitoline Hill, he says, where once stood the Temple of Jupiter, and where the Romans crowned their poets and triumphant generals. Wanting to be great again, the popes volunteer to rebuild the Capitoline, as do the wealthy Roman families, who sincerely believe they are descended from the same Roman Senators who kept the bread and circuses running on time through Visigoths and more. Michelangelo and Raphael crack their knuckles. New palaces are built on the Capitoline Hill, neoclassical inventions based on what artists thought ancient authors like Vitruvius were talking about. In time the population grows, and Rome’s wealth increases thanks to the Church and to the PR campaign of Petrarch and his followers. The empty parts of the inner city are re-colonized, by Cardinals building grand palaces, and poorer people building what they can to live near the Cardinals who give them employment. But it is all built out of the convenient stone that’s lying around, and on top of convenient foundations that used to be the buildings of Constantinian Rome when she boasted 1,000,000 souls.

Enter the Renaissance, Petrarch, and humanism. Petrarch writes of the glory that was Rome, and convinces Italy that, if they can reconstruct that, they can be great again, just as when they conquered the Goths and Germans. Popes and lords become hungry for the symbols of power which Rome once was. Petrarch reads his Cicero and his Sallust, and visits the empty center of the city. This is the Capitoline Hill, he says, where once stood the Temple of Jupiter, and where the Romans crowned their poets and triumphant generals. Wanting to be great again, the popes volunteer to rebuild the Capitoline, as do the wealthy Roman families, who sincerely believe they are descended from the same Roman Senators who kept the bread and circuses running on time through Visigoths and more. Michelangelo and Raphael crack their knuckles. New palaces are built on the Capitoline Hill, neoclassical inventions based on what artists thought ancient authors like Vitruvius were talking about. In time the population grows, and Rome’s wealth increases thanks to the Church and to the PR campaign of Petrarch and his followers. The empty parts of the inner city are re-colonized, by Cardinals building grand palaces, and poorer people building what they can to live near the Cardinals who give them employment. But it is all built out of the convenient stone that’s lying around, and on top of convenient foundations that used to be the buildings of Constantinian Rome when she boasted 1,000,000 souls.

Rome grows and refills and grows and refills from the outside in, with the Capitoline as a new center artificially reconstructed by Renaissance ambition. As the 18th and 19th centuries arrive, the city is full again, but the middle ring, between outside and center, is all the newest stuff, to the historian and tourist the least interesting. This is why everything that tourists come to see in Rome is a long bus ride from everything else, and why you have to go up and down a million exhausting hills to get anywhere. Rome has a belt of cultural no-man’s-land in and around it, separating the center from the Christian outskirts, and making it forever inconvenient.

In the 18th and 19th centuries we also start to have archaeology, and dig up the Forum, and begin to protect and reconstruct the ancient monuments, and recognize that this largely abandoned patch of valley behind the Capitoline Hill is, arguably, the most important couple blocks of real estate that has ever existed in the history of the world. We paint Romantic paintings of it, and sketch what it must have looked like once, and it becomes part of the coming-of-age of every elite young European to make the pilgrimage to it (that Freud so fears!) and see the relics of what once was Rome. Everywhere else the classical layer is under a pile of palaces and churches and pizzerias, but here in the precious Forum valley, between those hills that sheltered the first Romans, we have lifted the upper layers and exposed Rome’s ancient heart.

HELLO! I AM MUSSOLINI! I AM THE NEW ROME! MY EMPIRE WILL LAST 1000 YEARS! MY STUFF IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN THIS ANCIENT STUFF! WHEN I AM DONE, NO ONE WILL CARE ABOUT CLASSICAL RELICS ANYMORE! I AM GOING TO KNOCK DOWN ALL THE ANCIENT STUFF AND BUILD MY STUFF ON TOP!

Specifically Mussolini built a road straight through the middle of the Forum. Fascism was a strange moment in human history, and Rome’s, and left a lot of scars. One of them is the Via dei Fori Imperiali, a grand boulevard running along the Forum and around the Capitoline, which Mussolini built so he could have processions, and to declare to the world how sure he was that no one would care about the Roman relics he was paving over. They would not care about the Temple of Jupiter, or the Renaissance palace on top of it, but about the new monuments he carved into the city’s heart. Those, and he, would be remembered, Caesar and Augustus forgotten.

Specifically Mussolini built a road straight through the middle of the Forum. Fascism was a strange moment in human history, and Rome’s, and left a lot of scars. One of them is the Via dei Fori Imperiali, a grand boulevard running along the Forum and around the Capitoline, which Mussolini built so he could have processions, and to declare to the world how sure he was that no one would care about the Roman relics he was paving over. They would not care about the Temple of Jupiter, or the Renaissance palace on top of it, but about the new monuments he carved into the city’s heart. Those, and he, would be remembered, Caesar and Augustus forgotten.

To quote my favorite column by the old Anime Answerman: “Dear kid, please tell your friend that no one has ever been more wrong in the entire history of time.”

Mussolini, like the Visigoths, came but did not entirely go. One of his remnants is a system of large boulevards scarred into the face of the city, intended for his grand Fascist processions. Many of these are now difficult to eliminate, since car traffic in Rome is already a special kind of hell (fitting as a subsection of Circle 7 Part 2, I’d say, violence against ourselves and our creations, though it could be 4, hoarding/wasting, or yet another pouch of 8). The worst offender, though, is this road which is currently still covering up about a quarter of the ancient Forum, and also separates a quarter of the remaining Forum from the other half. It is this road that the new Mayor proposes to eliminate. The extra Fascist decoration which Mussolini added to the “wedding cake” will stay, the right call in my opinion, since Fascism is now one of Rome’s layers, just as much as the Visigothic scars on the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina. But lifting the road away will give us the true breadth of the Forum back in a way no pocket diagram can replicate. The transition will be painful for the FIATs and Vespas that now swarm where long ago the early Romans fought Etruscans and wild boar, but it is also an important validation of the Forum’s status as Rome’s most special spot. Everywhere else is layers. Everywhere else, when there’s Baroque on top of Renaissance on top of medieval, we leave it there. The altar stays behind the washing machine, and the need to open yet another catacomb is smaller than the need to have a working pizzeria. But in the Forum the layers have been lifted away. This one heart of one moment in Rome’s history, or at least one patch of about seven active centuries, we expose and preserve in honor of the importance that little spot has had as the definition of power, empire, war, and peace for Europe for 2,000 years. Thus, I hope you will all join me saying thank you to Mayor Marino.

The Forum is our relic of Rome’s antiquity, but it is not, for one who knows the city, the true proof that this is a great ancient capital. That would be clear even if not an inch of Roman marble remained in situ. The proof of Rome’s antiquity is its layout, the organic development of a wildly inconvenient but rich city plan, with those impassable hills at the center, the Tiber dividing the main city from the across-the-river part which is still the “new” part and still politically distinct, with its own soccer team, even after thousands of years. Antiquity is the nonsensical distribution of city mini-centers, the secondary hubs around the Vatican and St. John Lateran, the crowded shops clinging to the cliff-like faces of the hills, the Spanish Steps which are there because you have to go up that ridiculous hill and it’s really tall. Antiquity is not the Colosseum, it’s the fact that the Colosseum is smack inconveniently in the middle of a terrible traffic circle, definitely not where anyone would put a Colosseum on purpose if the modern city planners had a choice. Antiquity is structure, the presence of layers, unlike young, planned cities where everything is still in a place that makes sense because that city has only had one or two purposes throughout its history. Rome has had many purposes: shelter, commerce, conquest, post-conquest/plague refugee camp, religious capital, center of cultural rebirth, new capital, finally tourist pilgrimage site. All those Romes are in a pile, and the chaos that pile creates is the authentic ancient city. Rome is that cafe bathroom with a curved wall that proves it is where Caesar was assassinated. In another thousand years I don’t know what will be there, a space-ship docking station or a food cube kiosk, but whatever it is I know it will still have that curved back wall.

If you enjoyed this, see also my historical introduction to Florence.

FOOTNOTE: For those who care, the context of that Anime Answerman quotation:

Kid writing in: “Dear Anime Answerman, my friend tells me that Inuyasha is a more violent show than Elfen Leid, and I don’t believe them, but I can’t tell them they’re wrong because my Mom won’t let me watch Elfen Leid.”

Answerman: “Dear kid, please tell your friend that no one has ever been more wrong in the entire history of time.”