“The Borgias” vs. “Borgia: Faith and Fear” (accuracy in historical fiction)

There was a Borgia boom in 2011 when, aiming to capitalize on the commercial success of The Tudors, the television world realized there was one obvious way to up the ante. Not one but two completely unrelated Borgia TV series were made in 2011. Many have run across the American Showtime series The Borgias, but fewer people know about Borgia, also called Borgia: Faith and Fear, a French-German-Czech production released (in English) in the Anglophone world via Netflix. I am watching both and enjoying both. This unique phenomenon, two TV series made in the same year, modeled on the same earlier series and treating the same historical characters and events, is an amazing chance to look at different ways history can be used in fiction.

I am not evaluating these shows for their historical accuracy. I have been fortunate in that becoming an historian hasn’t stopped me from enjoying historical television. It’s a professional risk, and I know plenty of people whose ability to enjoy a scene is completely shattered if Emperor Augustus is eating a New World species of melon, or Anne Boleyn walks on screen wearing the wrong shade of green. I sympathize with the inability to ignore niggling errors, and I know any expert suffers from it, whether a physicist watching attempting-to-be-hard SF, or a doctor watching a medical show, or any sane person watching the Timeline movie. But over the years as my historical knowledge has increased so has my recognition of just how hard it is to make a historically accurate show, and how often historical accuracy comes into conflict with entertainment. More on that later...

As for the Borgias and the other Borgias:

The Borgias (Showtime) Borgia: Faith and Fear (International & Netflix)

- Bigger budget (gorgeous!) Smaller budget

- Shorter series/seasons Longer seasons, enabling slower pacing, more detail

- Bigger name actors Extremely international cast (accents sometimes strong)

- More glossing over details More historical details (can be more confusing as a result)

- Makes Cesare older than Giovanni/Juan Makes Giovanni/Juan older than Cesare (<= historians debate)

- Focus on Cesare as mature and grim Focus on Cesare as young and seeking his path

- Lots of typical TV sex and violence More period-feeling sex and violence

- Generally less historicity Generally more historicity

What do I mean by “more historicity”? While I enjoy both shows–both will pass the basic TV test of making you enjoy yourself for the 50 minutes you spend in a chair watching them–the international series consistently succeeded in making the people and their behavior feel more period. Here are two sample scenes that demonstrate what I mean:

Borgia: Faith and Fear, episode 1. One of the heads of the Orsini family bursts into his bedroom and catches Juan (Giovanni) Borgia in flagrante with his wife. Juan grabs his pants and flees out the window as quickly as he can. Now here is Orsini alone with his wife. [The audience knows what to expect. He will shout, she will try to explain, he will hit her, there will be tears and begging, and, depending on how bad a character the writers are setting up, he might beat her really badly and we’ll see her in the rest of this episode all puffy and bruised, or if they want him to be really bad he’ll slam her against something hard enough to break her neck, and he’ll stare at her corpse with that brutish ambiguity where we’re not sure if he regrets it.] Orsini grabs the iron fire poker and hits his wife over the head, full force, wham, wham, dead. He drops the fire poker on her corpse and walks briskly out of the room, leaving it for the servants to clean up. Yes. That is the right thing, because this is the Renaissance, and these people are terrible. When word gets out there is concern over a possible feud, but no one ever comments that Orsini killing his wife was anything but the appropriate course. That is historicity, and the modern audience is left in genuine shock.

Borgia: Faith and Fear, episode 1. One of the heads of the Orsini family bursts into his bedroom and catches Juan (Giovanni) Borgia in flagrante with his wife. Juan grabs his pants and flees out the window as quickly as he can. Now here is Orsini alone with his wife. [The audience knows what to expect. He will shout, she will try to explain, he will hit her, there will be tears and begging, and, depending on how bad a character the writers are setting up, he might beat her really badly and we’ll see her in the rest of this episode all puffy and bruised, or if they want him to be really bad he’ll slam her against something hard enough to break her neck, and he’ll stare at her corpse with that brutish ambiguity where we’re not sure if he regrets it.] Orsini grabs the iron fire poker and hits his wife over the head, full force, wham, wham, dead. He drops the fire poker on her corpse and walks briskly out of the room, leaving it for the servants to clean up. Yes. That is the right thing, because this is the Renaissance, and these people are terrible. When word gets out there is concern over a possible feud, but no one ever comments that Orsini killing his wife was anything but the appropriate course. That is historicity, and the modern audience is left in genuine shock.

The Borgias, episode 1. We are facing the papal election of 1492. Another Cardinal confronts Rodrigo Borgia in a hallway. It has just come out that Borgia has been committing simony, i.e. taking bribes. Our modern audience is shocked! Shocked, I say! That a candidate for the papacy would be corrupt and take bribes! Our daring Cardinal confronts Borgia, saying he too is shocked! Shocked! This is no longer a matter of politics but principle! He will oppose Borgia with all his power, because Borgia is a bad person and should not sit on the Throne of St. Peter! See, audience! Now is the time to be shocked! No. This is not the Renaissance, this is modern sensibilities about what we think should’ve been shocking in the Renaissance. After the election this same Cardinal will be equally shocked that the Holy Father has a mistress, and bastards. Ooooh. Because that would be shocking in 2001, but in 1492 this had been true of every pope for the past century. In fact, Cardinal Shocked-all-the-time, according to the writers you are supposed to be none other than Giuliano della Rovere. Giuliano “Battle-Pope” della Rovere! You have a mistress! And a daughter! And a brothel! And an elephant! And take your elephant to your brothel! And you’re stalking Michelangelo! And foreign powers lent you 300,000 ducats to spend bribing other people to vote for you in this election! And we’re supposed to believe you are shocked by simony? That is not historicity. It is applying some historical names to some made-up dudes and having them lecture us on why be should be shocked.

The Borgias, episode 1. We are facing the papal election of 1492. Another Cardinal confronts Rodrigo Borgia in a hallway. It has just come out that Borgia has been committing simony, i.e. taking bribes. Our modern audience is shocked! Shocked, I say! That a candidate for the papacy would be corrupt and take bribes! Our daring Cardinal confronts Borgia, saying he too is shocked! Shocked! This is no longer a matter of politics but principle! He will oppose Borgia with all his power, because Borgia is a bad person and should not sit on the Throne of St. Peter! See, audience! Now is the time to be shocked! No. This is not the Renaissance, this is modern sensibilities about what we think should’ve been shocking in the Renaissance. After the election this same Cardinal will be equally shocked that the Holy Father has a mistress, and bastards. Ooooh. Because that would be shocking in 2001, but in 1492 this had been true of every pope for the past century. In fact, Cardinal Shocked-all-the-time, according to the writers you are supposed to be none other than Giuliano della Rovere. Giuliano “Battle-Pope” della Rovere! You have a mistress! And a daughter! And a brothel! And an elephant! And take your elephant to your brothel! And you’re stalking Michelangelo! And foreign powers lent you 300,000 ducats to spend bribing other people to vote for you in this election! And we’re supposed to believe you are shocked by simony? That is not historicity. It is applying some historical names to some made-up dudes and having them lecture us on why be should be shocked.

These are just two examples, but typify the two series. The Borgias toned it down: consistently throughout the series, everyone is simply less violent and corrupt than they actually historically, documentably were. Why would sex-&-violence Showtime tone things down? I think because they were afraid of alienating their audience with the sheer implausibility of what the Renaissance was actually like. Rome in 1492 was so corrupt, and so violent, that I think they don’t believe the audience will believe them if they go full-on. Almost all the Cardinals are taking bribes? Lots, possibly the majority of influential clerics in Rome overtly live with mistresses? Every single one of these people has committed homicide, or had goons do it? Wait, they all have goons? Even the monks have goons? It feels exaggerated. Showtime toned it down to a level that matches what the typical modern imagination might expect.

Borgia: Faith and Fear did not tone it down. A bar brawl doesn’t go from insult to heated words to slamming chairs to eventually drawing steel, it goes straight from insult to hacking off a body part. Rodrigo and Cesare don’t feel guilty about killing people, they feel guilty the first time they kill someone dishonorably. Rodrigo is not being seduced by Julia Farnese and trying to hide his shocking affair; Rodrigo and Julia live in the papal palace like a married couple, and she’s the head of his household and the partner of his political labors, and if the audience is squigged out that she’s 18 and he’s 61 then that’s a fact, not something to try to SHOCK the audience with because it’s so SHOCKING shock shock. Even in other details, Showtime kept letting modern sensibilities leak in. Showtime’s 14-year-old Lucrezia is shocked (as a modern girl would be) that her father wants her to have an arranged marriage, while B:F&F‘s 14-year-old Lucrezia is constantly demanding marriage and convinced she’s going to be an old maid if she doesn’t marry soon, but is simultaneously obviously totally not ready for adult decisions and utterly ignorant of what marriage will really mean for her. It communicates what was terrible about the Renaissance but doesn’t have anyone on-camera objecting to it, whereas Showtime seemed to feel that the modern audience needed someone to relate to who agreed with us. And, for a broad part of the modern TV-watching audience, they may well be correct. I wouldn’t be surprised if many viewers find The Borgias a lot more approachable and comfortable than its more period-feeling rival.

Borgia: Faith and Fear also didn’t tone down the complexity, or rather toned it down much less than The Borgias. This means that it is much harder to follow. There are many more characters, more members of every family, the complex family structures are there, the side-switching. I had to pause two or three times an episode to explain to those watching with me who Giodobaldo da Montefeltro was, or whatever. There’s so much going on that the Previously On recap gives up and just says: “The College of Cardinals is controlled by the sons of Rome’s powerful Italian families. They all hate each other. The most feared is the Borgias.” They wisely realized you couldn’t possibly follow everything that’s going on in Florence as well as Rome, so they just periodically have someone receive a letter summarizing wacky Florentine hijinx, as we watch adorable little Giovanni “Leo” de Medici (played by the actor who is Samwell Tarly in Game of Thrones) get more and more overwhelmed and tired. Showtime’s series oversimplifies more, but that is both good and bad, in its way. The audience needs to follow the politics, after all, and we can only take so much summary. The Tudors got away with a lot by having lectures on what it means to be Holy Roman Emperor delivered by shirtless John Rhys Meyers as he stalked back and forth screaming in front of beautiful upholstery, and he’s a good enough actor that he could scream recipes for shepherd’s pie and we’d still sit through about a minute of it. The Borgia shows have even more complicated politics for us to choke down.

Now, historians aren’t certain of Cesare’s birth date. He may be the eldest of his full siblings, or second.

The difference between Cesare as elder brother and Cesare as younger brother in the shows is fascinating. Showtime’s Big Brother Cesare is grim, disillusioned, making hard decisions to further the family’s interests even if the rest of the family isn’t yet ready to embrace such means. B:F&F‘s Little Brother Cesare is starved for affection, uncertain about his path, torn about his religion, and slowly growing up in a baby-snake-that-hasn’t-yet-found-its-venom kind of way.

Both are fascinating, utterly unrelated characters, and all the subsequent character dynamics are completely different too. Giovanni/Juan is utterly different in each, since Big Brother Cesare requires a playful and endearing younger brother, whose death is already being foreshadowed in episode 1 with lines like “It’s the elder brother’s duty to protect the younger,” while Little Brother Cesare requires a conceited, bullying Giovanni/Juan undeserving of the affection which Rodrigo ought to be giving to smarter, better Cesare. Elder Brother Cesare also requires different close friends, giving him natural close relationships with figures like the Borgias’ famous family assassin Michelotto Corella, who can empathize with him about using dark means in a world that isn’t quite OK with it.

There are other age-heirarchy-related differences as well.

Younger Brother Cesare gets chummy classmate buddies Alessandro Farnese and Giovanni “Leo” de Medici, who must balance their own precarious political careers with the terrifying privilege of being the best friends of young Cesare as he grows into his powers and toward the season 1 finale “The Serpent Rises.” All this makes the two series taken together a fascinating example of how squeezing historical events into the requirements of narrative tropes makes one simple change–older brother trope vs. younger brother trope–lead logically to two completely different stories. I think both versions are very powerful, and the person they made out of the historical Cesare is different and original in each, and worth exploring.

The great writing test is how to do Giovanni/Juan’s murder. Since some people do and some don’t know their gory Borgia history, part of the audience knows it’s coming, and part doesn’t. Historians still aren’t sure who did it, whether it was Cesare or someone else, and what the motive was. Thus the writers get to decide how heavily to foreshadow the death, how to do the reveal, what character(s) to make the perpetrator(s), and what motives to stress. I will not spoil what either series chose, but I will say that it is very challenging writing a murder when you know some audience members have radically different knowledge from others, and that I think Borgia: Faith and Fear used that fact brilliantly, and tapped the tropes of murder mystery very cleverly, when scripting the critical episode. The Borgias was less creative in its presentation.

But what about historical accuracy?

I said before that I am not evaluating these shows for their historical accuracy. Shows ignoring history or changing it around does bother me sometimes, especially if a show is very good and ought to know better. The superb HBO series Rome, which does an absolutely unparalleled job presenting Roman social class, slavery, and religion, nonetheless left me baffled as to why a studio making a series about the Julio-Claudians would feel driven to ignore the famous historical allegations of orgies and bizarre sex preserved in classical sources and substitute different orgies and bizarre sex. The original orgies and bizarre sex were perfectly sufficient! But in general I tend to be extremely patient with historically inacurate elements within my history shows, moreso than many non-historians I know, who are bothered by our acute modern anachronism-radar (on the history of the senes of anachronism and its absence in pre-modern psychology, see Michael Wood: Forgery, Replica, Fiction). For me, though, I have learned to relax and let it go.

I remember the turning point moment. I was watching an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer with my roommates, and it went into a backstory flashback set in high medieval Germany. “Why are you sighing?” one asked, noticing that I’d laid back and deflated rather gloomily. I answered: “She’s not of sufficiently high social status to have domesticated rabbits in Northern Europe in that century. But I guess it’s not fair to press a point since the research on that hasn’t been published yet.” It made me laugh, also made me think about how much I don’t know, since I hadn’t known that a week before. For all the visible mistakes in these shows, there are even more invisible mistakes that I make myself because of infinite details historians haven’t figured out yet, and possibly never will. There are thousands of artifacts in museums whose purposes we don’t know. There are bits of period clothing whose functions are utter mysteries. There are entire professions that used to exist that we now barely understand. No history is accurate, not even the very best we have.

Envision a scene in which two Renaissance men are hanging out in a bar in Bologna with a prostitute. Watching this scene, I, with my professional knowledge of the place and period, notice that there are implausibly too many candles burning, way more than this pub could afford, plus what they paid for that meal is about what the landlord probably earns in a month, and the prostitute isn’t wearing the mandatory blue veil required for prostitutes by Bologna’s sumptuary laws. But if I showed it to twenty other historians they would notice other things: that style of candlestick wasn’t possible with Italian metalwork of the day, that fabric pattern was Flemish, that window wouldn’t have had curtains, that dish they’re eating is a period dish but from Genoa, not Bologna, and no Genoese cook would be in Bologna because feud bla bla bla. So much we know. But a person from the period would notice a thousand other things: that nobody made candles in that exact diameter, or they butchered animals differently so that cut of steak is the wrong shape, or no bar of the era would have been without the indispensable who-knows-what: a hat-cleaning lady, a box of kittens, a special shape of bread. All historical scenes are wrong, as wrong as a scene set now would be which had a classy couple go to a formal steakhouse with paper menus and an all-you-can-eat steak buffet. All the details are right, but the mix is wrong.

In a real historical piece, if they tried to make everything slavishly right any show would be unwatchable, because there would be too much that the audience couldn’t understand. The audience would be constantly distracted by details like un-filmably dark building interiors, ugly missing teeth, infants being given broken-winged songbirds as disposable toys to play with, crush, and throw away, and Marie Antoinette relieving herself on the floor at Versailles. Despite its hundreds of bathrooms, one of Versailles’ marks of luxury was that the staff removed human feces from the hallways regularly, sometimes as often as twice a day, and always more than once a week. We cannot make an accurate movie of this – it will please no one. The makers of the TV series Mad Men recognized how much an accurate depiction of the past freaks viewers out – the sexual politics, the lack of seat belts and eco-consciousness, the way grown-ups treat kids. They focused just enough on this discomfort to make it the heart of a powerful and successful show, but there even an accurate depiction of attitudes from a few decades ago makes all the characters feel like scary aliens. Go back further and you will have complete incomprehensibility.

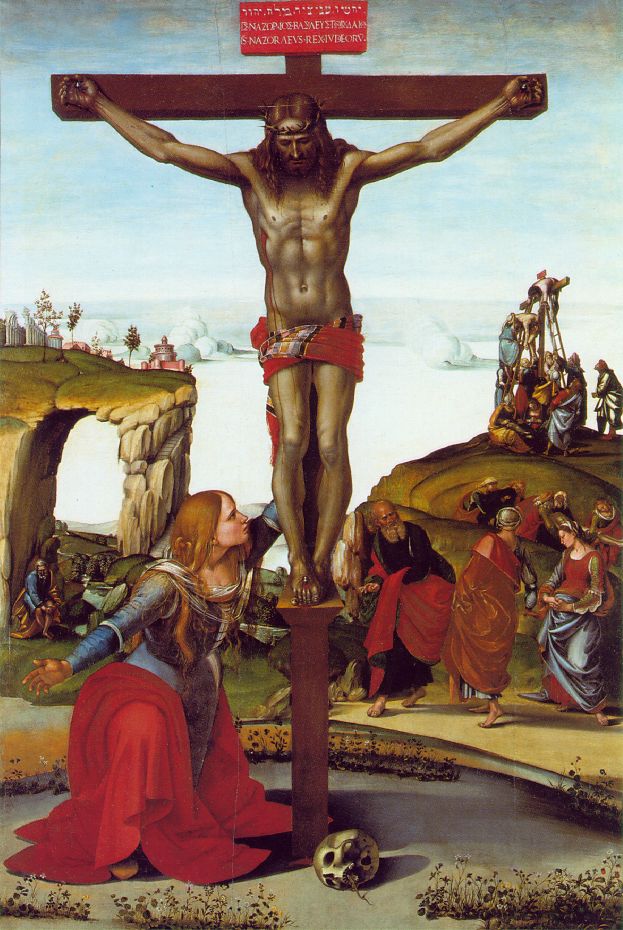

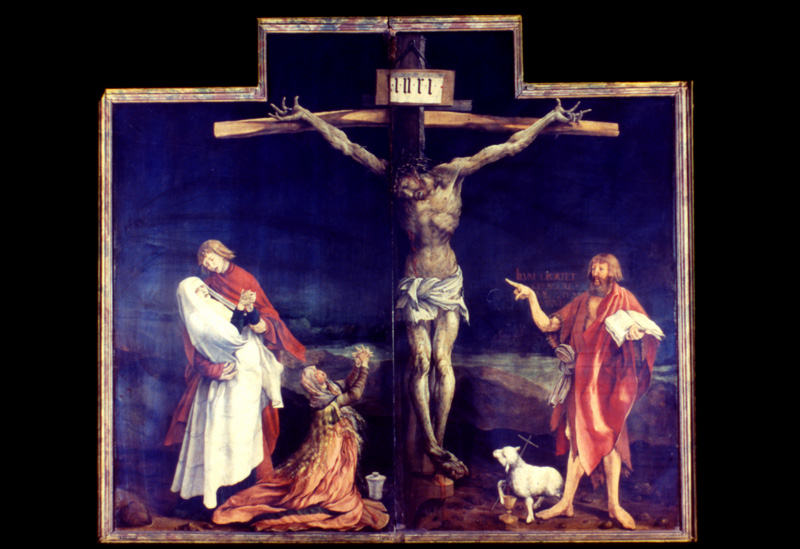

Even costuming accuracy can be a communications problem, since modern viewers have certain associations that are hard to unlearn. Want to costume a princess to feel sweet and feminine? The modern eye demands pink or light blue, though the historian knows pale colors coded poverty. Want to costume a woman to communicate the fact that she’s a sexy seductress? The audience needs the bodice and sleeves to expose the bits of her modern audiences associate with sexy, regardless of which bits would plausibly have been exposed at the time. I recently had to costume some Vikings, and was lent a pair of extremely nice period Viking pants which had bold white and orange stripes about two inches wide. I know enough to realize how perfect they were, and that both the expense of the dye and the purity of the white would mark them as the pants of an important man, but that if someone walked on stage in them the whole audience would think: “Why is that Viking wearing clown pants?” Which do you want, to communicate with the audience, or to be accurate? I choose A.

Thus, rather than by accuracy, I judge this type of show by how successfully the creators of an historical piece have chosen wisely from what history offered them in order to make a good story. The product needs to communicate to the audience, use the material in a lively way, change what has to be changed, and keep what’s awesome. If some events are changed or simplified to help the audience follow it, that’s the right choice. If some characters are twisted a bit, made into heroes or villains to make the melodrama work, that too can be the right choice. If you want to make King Arthur a woman, or have Mary Shelley sleep with time-traveling John Hurt, even that can work if it serves a good story. Or it can fail spectacularly, but in order to see what people are trying to do I will give the show the benefit of the doubt, and be patient even if poor Merlin is in the stocks being pelted with tomatoes. (By the way, if you’re trying to watchthe BBC’s Merlin and decide it’s not set in the past but on a terraformed asteroid populated by vat-cultured artificial people who have been given a 20th century moral education and then a book on medieval society and told to follow its advice, everything suddenly makes perfect sense!)

I am not meaning to pick a fight here with people who care deeply about accuracy in historical fiction. I respect that it bothers some people, and also that there is great merit in getting things right. Research and thoroughness are admirable, and, just as it requires impressive virtuosity to cook a great meal within strict diet constraints, like gluten free or vegan, so it takes great virtuosity to tell a great story without cheating on the history. I am simply saying that, while accuracy is a merit, it is not more important to me than other merits, especially entertainment value in something which is intended as entertainment.

This is also why I praise Borgia: Faith and Fear for what I call its “historicity” rather than its “accuracy”. It takes its fair share of liberties, as well it should if it wants a modern person to sit through it. But it also succeeds in making the characters feel un-modern in a way many period pieces don’t try to do. It is a bit alienating but much more powerful. It is more accurate, yes, but it isn’t the accuracy alone that makes it good, it’s the way that accuracy serves the narrative and makes it exceptional, as truffle raises a common cream sauce to perfection. Richer characters, more powerful situations, newer, stranger ideas that challenge the viewers, these are the produce of B:F&F‘s historicity, and bring a lot more power to it than details like accurately-colored dresses or perfectly period utensils, which are admirable, but not enriching.

Final evaluation:

In the end, both these shows are successfully entertaining, and were popular enough to get second and third seasons in which we can enjoy such treats as Machiavelli and Savonarola (Showtime’s planned 4th season has been cancelled, though there are motions to fight that). Showtime’s series is more approachable and easier to understand, but Borgia: Faith and Fear much more interesting, in my opinion, and also more valuable. The Borgias thrills and entertains, but Borgia: Faith and Fear also succeeds in showing the audience how terrible things were in the Renaissance, and how much progress we’ve made. It de-romanticizes. It feels period. It has guts. It has things the audience is not comfortable with. It has people being nasty to animals. It has disfigurement. It has male rape. When it’s time for a public execution, the mandatory cheap thrill of this genre, it goes straight for just about the nastiest Renaissance method I know of, sawing a man in half lengthwise starting at the crotch and moving along the spine. The scene leaves the audience less titillated than appalled, and glad that we don’t do that anymore.

Are they historically accurate? Somewhat. They’re both quite thorough in their research, but both change things. The difference is what they change, and why. If Borgia: Faith and Fear wants do goofy things with having the Laocoon sculpture be rediscovered early, I sympathize with the authors’ inability to resist the too-perfect metaphor of Rodrigo Borgia looking at this sculpture of a father and his two sons being dragged down by snakes. It adds to the show, even if it’s a bit distracting. But if The Borgias wants to make Giuliano della Rovere into a righteous defender of virtue, they throw away a great and original historical character in exchange for a generic one. It makes the whole set of events more generic, and that is the kind of change I object to, not as an historian, but as someone who loves good fiction, and wants to see it be the best it can be.

(I do get one nitpick. When Michelangelo had a cameo in The Borgias, why did he speak Italian when everyone else was speaking English? What was that supposed to communicate? Is everyone else supposed to be speaking Latin all the time? Is the audience supposed to know he is Italian but not think about it with everyone else? I am confused!)

If you have not already read it, see my Machiavelli Series for historical background on the Borgias. For similar analysis of TV and history, I also highly recommend my essay on Tor.com about Shakespeare in the Age of Netflix (focusing on the BBC “The Hollow Crown” adaptation of Shakespeare’s Henriad).

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)