Black Death, COVID, and Why We Keep Telling the Myth of a Renaissance Golden Age and Bad Middle Ages

“If the Black Death caused the Renaissance, will COVID also create a golden age?”

“If the Black Death caused the Renaissance, will COVID also create a golden age?”

Versions of this question have been going around as people, trying to understand the present crisis, reach for history’s most famous pandemic. Using history to understand our present is a great impulse, but it means some of the false myths we tell about the Black Death and Renaissance are doing new damage, one of the most problematic in my view being the idea that sitting back and letting COVID kill will somehow by itself naturally make the economy turn around and enter a period of growth and rising wages.

Brilliant Medievalists have been posting Black Death pieces correcting misconceptions and flailing as one does when an error refuted 50 times returns the 51st (The Middle Ages weren’t dark and bad compared to the Renaissance!!!). As a Renaissance historian, I feel it’s my job to shoulder the other half of the load by talking about what the Renaissance was like, confirming that our Medievalists are right, it wasn’t a better time to live than the Middle Ages, and to talk about where the error comes from, why we think of the Renaissance as a golden age, and where we got the myth of the bad Middle Ages.

Only half of this is a story about the Renaissance. The other half is later: Victorian Britain, Italy’s unification, World Wars I and II, the Cold War, ages in which the myth of the golden Renaissance was appropriated and retold. And yes, looking at the Black Death and Renaissance is helpful for understanding COVID-19’s likely impact, but in addition to looking at 1348 we need to look at its long aftermath, at the impact Yersinia Pestis had on 1400, and 1500, and 1600, and 1700. So:

- This post is for you if you’ve been wondering whether Black Death => Renaissance means COVID => Golden Age, and you want a more robust answer than, “No no no no no!”

- This post is for you if you’re tired of screaming The Middle Ages weren’t dark and bad! and want somewhere to link people to, to show them how the myth began.

- This post is for you if you want to understand how an age whose relics make it look golden in retrospect can also be a terrible age to live in.

- And this post is for you if want to ask what history can tell us about 2020 and come away with hope. Because comparing 2020 to the Renaissance does give me hope, but it’s not the hope of sitting back expecting the gears of history to grind on toward prosperity, and it’s not the hope for something like the Renaissance—it’s hope for something much, much better, but a thing we have to work for, all of us, and hard.

I started writing this post a few weeks ago but rapidly discovered that a thorough answer will be book-length (the book’s now nearly done in fact). What I’m sharing now is just a precis, the parts I think you’ll find most useful now. So sometimes I’ll make a claim without examples, or move quickly over important things, just linking to a book instead of explaining, because my explanation is approaching 100,000 words. That book will come, and soon, but meanwhile please trust me as I give you just urgent parts, and I promise more will follow.

Now, to begin, the phrase “golden age” really invokes two different unrelated things:

(1) an era that achieved great things, art, science, innovation, literature, an era whose wondrous achievements later eras marvel at,

(2) a good era to live, prosperous, thriving, stable, reasonably safe, with chances for growth, social ascent, days when hard work pays off, in short an era which—if you had to be stranded in some other epoch of history—you’d be likely to choose.

The Renaissance fits the first—we line up to see its wonders in museums—but it absolutely positively no-way-no-how fit the second, and that’s a big part of where our understandings of Renaissance vs. Medieval go wrong. So, our outline for today:

- Renaissance Life was Worse than the Middle Ages (super-compressed version)

- Where did the myth come from in the first place? (a Renaissance story)

- Why is the myth of a golden Renaissance retold so much? (a post-Renaissance story)

- Conclusion: We Should Aim for Something Better than the Renaissance

It’s also important to begin this knowing that I love the Renaissance, I wouldn’t have dedicated my life to studying it if I didn’t, it’s an amazing era. I disagree 100% with people who follow “The Middle Ages weren’t really a Dark Age!” with “The Renaissance sucks, no one should care about it!” The Renaissance was amazing, equally amazing as the Middle Ages, or antiquity, or now. I don’t love the Renaissance for being perfect. I love it because it was terrible yet still achieved so much. I love it because, when I read a letter where a woman talks of a nearby city burning, and armies approaching, and a friend who just died of the plague, and letter also talks about ideas for how to remedy these evils, and Xenophon’s advice for times of war, and how Plato and Seneca differ in their advice on patience, and the marvelous new fresco that’s been finished in the city hall. To find these voices of people who faced all that yet still came through it brimming with ideas and making art, that makes me love the human species all the more. And gives me hope.

In Florence, there are little kiosks near the David where you can buy replicas of it, and alongside the plain ones they have copies dipped in glitter paint, so the details of Michelangelo’s design are all obscured with globs of sparkling goo. That’s what the golden age myth does to the Renaissance. So when I say the Renaissance was grim and horrible, I’m not saying we shouldn’t study it it, I just want you to scrape off the glitter paint and see the details underneath: damaged, imperfect, a strange mix of ancient and new, doing its best to compensate for flaws in the material and mistakes made early on when teamwork failed, and violent too—David is, after all, about to kill an enemy, a celebration of a conquest, not a peace. Glitter drowns all that out, and this is why, while the myth of the golden Renaissance does terrible damage to how we understand the Middle Ages, it does just as much damage to how we understand the Renaissance. So let’s take a quick peek beneath the glitter, and then, more important, let’s talk about where that suffocating glitter comes from in the first place.

In Florence, there are little kiosks near the David where you can buy replicas of it, and alongside the plain ones they have copies dipped in glitter paint, so the details of Michelangelo’s design are all obscured with globs of sparkling goo. That’s what the golden age myth does to the Renaissance. So when I say the Renaissance was grim and horrible, I’m not saying we shouldn’t study it it, I just want you to scrape off the glitter paint and see the details underneath: damaged, imperfect, a strange mix of ancient and new, doing its best to compensate for flaws in the material and mistakes made early on when teamwork failed, and violent too—David is, after all, about to kill an enemy, a celebration of a conquest, not a peace. Glitter drowns all that out, and this is why, while the myth of the golden Renaissance does terrible damage to how we understand the Middle Ages, it does just as much damage to how we understand the Renaissance. So let’s take a quick peek beneath the glitter, and then, more important, let’s talk about where that suffocating glitter comes from in the first place.

Part 1: Renaissance Life was Worse than the Middle Ages (super-condensed version)

The Renaissance was like Voldemort, terrible, but great.

On February 25th 1506, Ercole Bentivoglio, commander of Florence’s armies, wrote to Machiavelli. He had just read Machiavelli’s Deccenale primo, a history in verse of the events of the last decade. Bentivoglio urged Machiavelli to continue and expand the history, not for them, but for future generations, so that:

“knowing our wretched fortune in these times, they should not blame us for being bad defenders of Italic honor, and so they can weep with us over our and their misfortune, knowing from what a happy state we fell within brief time into such disaster. For if they did not see this history, they would not believe what prosperity Italy had before, since it would seem impossible that in so few days our affairs could fall to such great ruin.”

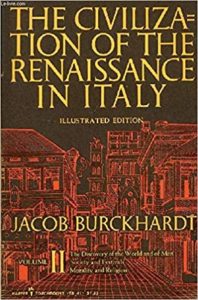

Of these days of precipitous ruin, Burkhardt, founder of modern Renaissance studies, wrote in 1869:

“The first decades of the sixteenth century, the years when the Renaissance attained its fullest bloom, were not favorable to a revival of patriotism; the enjoyment of intellectual and artistic pleasures, the comforts and elegancies of life, and the supreme interests of self-development, destroyed or hampered love of country.” (The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, end of Part 1)

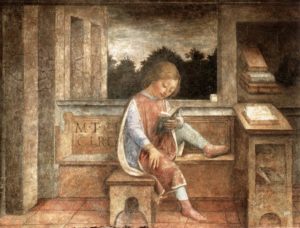

Burkhardt seems to be describing a different universe from Bentivoglio, so desperate to prove to posterity that he tried his failing best to defend his homeland’s honor. Yet this was the decade that produced Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, Michelangelo’s David, Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin, Bramante’s design for the new St. Peter’s Basilica, Josquin des Prez’s El grillo (the Cricket), the first chapters of Ariosto’s epic Orlando Furioso, and Castiglione’s first courtly works at the court of Urbino, soon to be immortalized in the Courtier as the supreme portrait of Renaissance culture. These masterworks do indeed seem to project a world of enjoyment and artistic pleasure in utter disconnect with Bentivoglio’s despair. Can this be the same Renaissance?

Burkhardt seems to be describing a different universe from Bentivoglio, so desperate to prove to posterity that he tried his failing best to defend his homeland’s honor. Yet this was the decade that produced Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, Michelangelo’s David, Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin, Bramante’s design for the new St. Peter’s Basilica, Josquin des Prez’s El grillo (the Cricket), the first chapters of Ariosto’s epic Orlando Furioso, and Castiglione’s first courtly works at the court of Urbino, soon to be immortalized in the Courtier as the supreme portrait of Renaissance culture. These masterworks do indeed seem to project a world of enjoyment and artistic pleasure in utter disconnect with Bentivoglio’s despair. Can this be the same Renaissance?

This double vision is authentic to the sources. If we read treatises, orations, dedicatory prefaces, writings on art or courtly conduct, and especially if we read works written about this period a few decades later—like Vasari’s Lives of the Artists which will be the first to call this age a rinascita—we see what Jacob Burkhardt described, and what popular understandings of the Renaissance focus on: a self-conscious golden age bursting with culture, art, discovery, and vying with the ancients for the title of Europe’s most glorious age. Burkhardt’s assessment was correct, if we look only at the sources he was looking at. If instead we read the private letters which flew back and forth between Machiavelli and his correspondents we see terror, invasion, plague deaths, a desperate man scrambling to even keep track of the ever-moving threats which hem his fragile homeland in from every side, as friends and family beg for frequent letters, since every patch of silence makes them fear the loved one might be dead.

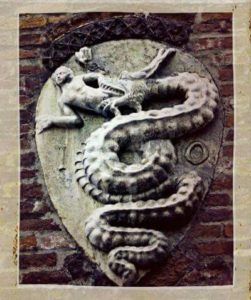

Machiavelli’s correspondent, Ercole Bentivoglio, typifies the tangled political web which shaped these years. His father had been Sante Bentivoglio, who began as a blacksmith’s son and common laborer but was identified as an illegitimate member of the Bentivoglio family that dominated Bologna (remember Gendry in Game of Thrones?), so Sante was called to rule Bologna for a while when the only other adult Bentivoglio was murdered in an ambush, and young Ercole grew up in a quasi-princely court with all the grandeur we now visit in museums. Ercole’s mother was Ginevra Sforza, an illegitimate niece of Francesco Sforza who had recently conquered Milan, replacing the earlier Visconti dukes who had in turn seized the throne by treachery fifty-five years before. Renaissance politics isn’t turtles all the way down, it’s murders and betrayals all the way down.

Why was life in the Renaissance so bad? This is going to be a tiny compressed version of what in the book will be 100 pages, but for now I’ll focus on why the Renaissance was not a golden age to actually live in, even if it was a golden age in terms of what it left behind.

Let’s look at life expectancy: In Italy, average life expectancies in the solidly Medieval 1200s were 35-40, while by the year 1500 (definitely Renaissance) life expectancy in Italian city states had dropped to 18.

It’s striking how consistently, when I use these numbers live, the shocked and mournful silence is followed by a guy objecting: those numbers are deceptive, you’re including infant mortality—voiced as if this observation should discredit them. Yes, the average of 18 does include infant mortality, but the Medieval average of 35 includes it too, so the drop is just as real. If you want we can exclude those who die before age 12, and we do get a smaller total drop then, average age of death 54 in the 1200s dropping to 45-48 in 1500, so only a 12-16% drop instead of 48%, but the more we zoom the grimmer the Renaissance half proves. Infant mortality (within 12 months) averaged 28% both before and after 1348, so the big drop from Medieval to Renaissance Italy is actually kids who made it past the first year, only to die in years 2-12 from new diseases. We also think of the dangers of childbirth as lowering women’s lifespans, but death from childbirth stayed steady from Medieval to Renaissance at (for Tuscany) 1 death per 40 births, while the increase in war and violence made adult male mortality far higher than female even with the childbirth threat. If we look at the 20% of people who lived longest in Renaissance Italy it’s almost entirely widows and nuns, plus a few diehards like Titian, and poor exiled Cardinal da Costa of Portugal languishing in Rome to the age of 102, with everyone he’d known in the first 2/3rds of his life long gone. Kids died more in the Renaissance, adults died more, men died more, we have the numbers, but I find it telling how often people who hear these numbers try to discredit them, search for a loophole, because these facts rub against our expectations. We didn’t want a wretched golden age. (Demographics are, of course, an average, and different bits of Europe varied, but I’m using the numbers for the big Italian city-states precisely because they’re the bit of Europe we most associate with the golden Renaissance, so if it’s true there, it’s true of the Renaissance you were imagining.)

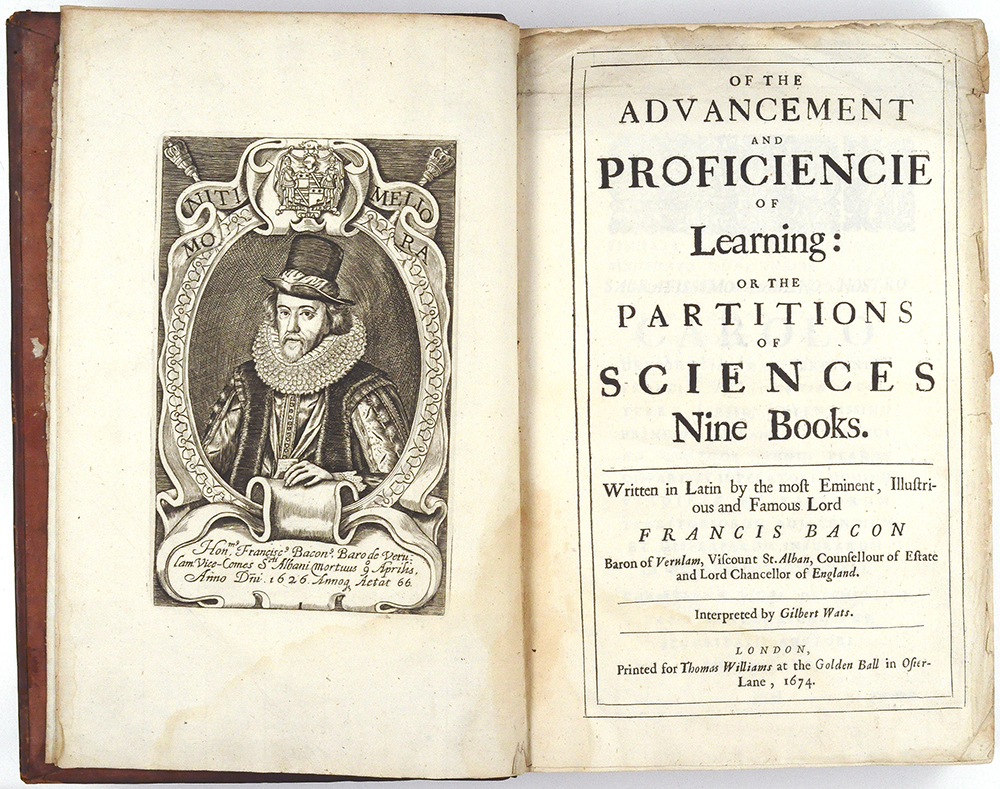

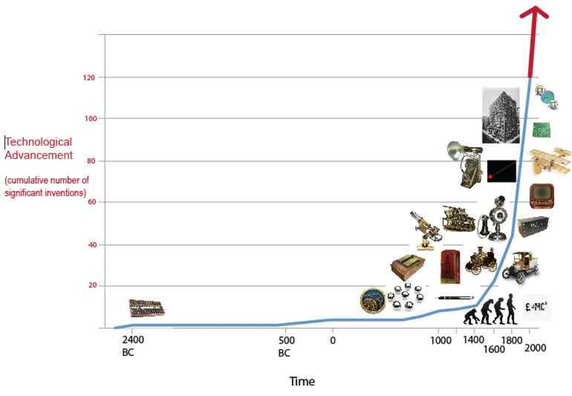

Why did life expectancy drop? Counter-intuitively the answer is, largely, progress.

War got worse, for one. Over several centuries, innovations in statecraft and policy (which would continue gradually for centuries more) had increased the centralization of power in the hands of kings and governments, especially their ability to gather funds, which meant they could raise larger armies and have larger, bloodier wars. Innovations in metallurgy, chemistry, and engineering also made soldiers deadlier, with more artillery, more lethal weapons, more ability to knock a town’s walls down and kill everyone inside, new daggers designed to leave wounds that would fester, or anti-personnel artillery designed to slice a line of men in half. Thus, while both the Middle Ages and Renaissance had lots of wars, Renaissance wars were larger and deadlier, involving more troops and claiming more lives, military and civilian—this wasn’t a sudden change, it was a gradual one, but it made a difference.

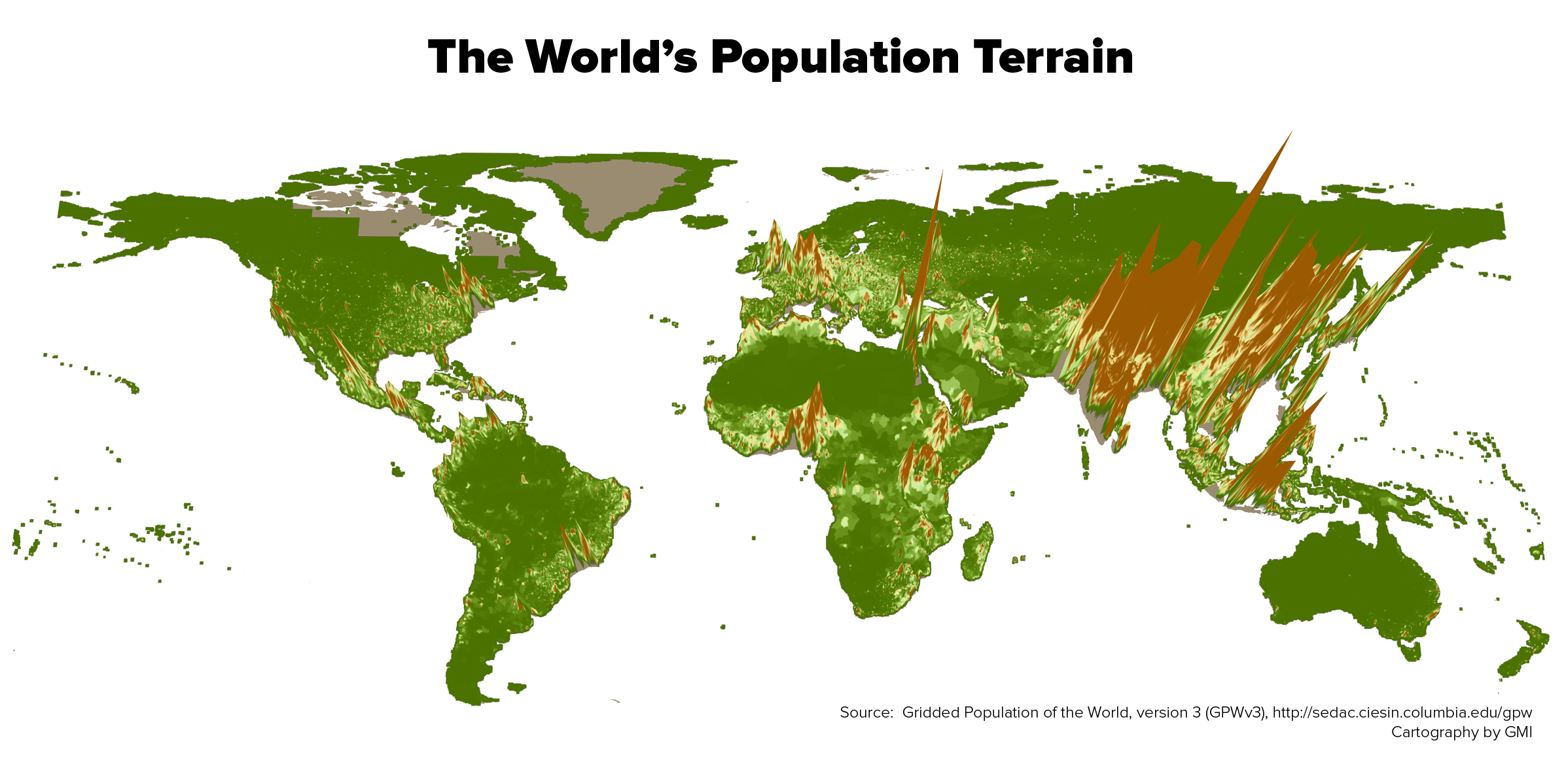

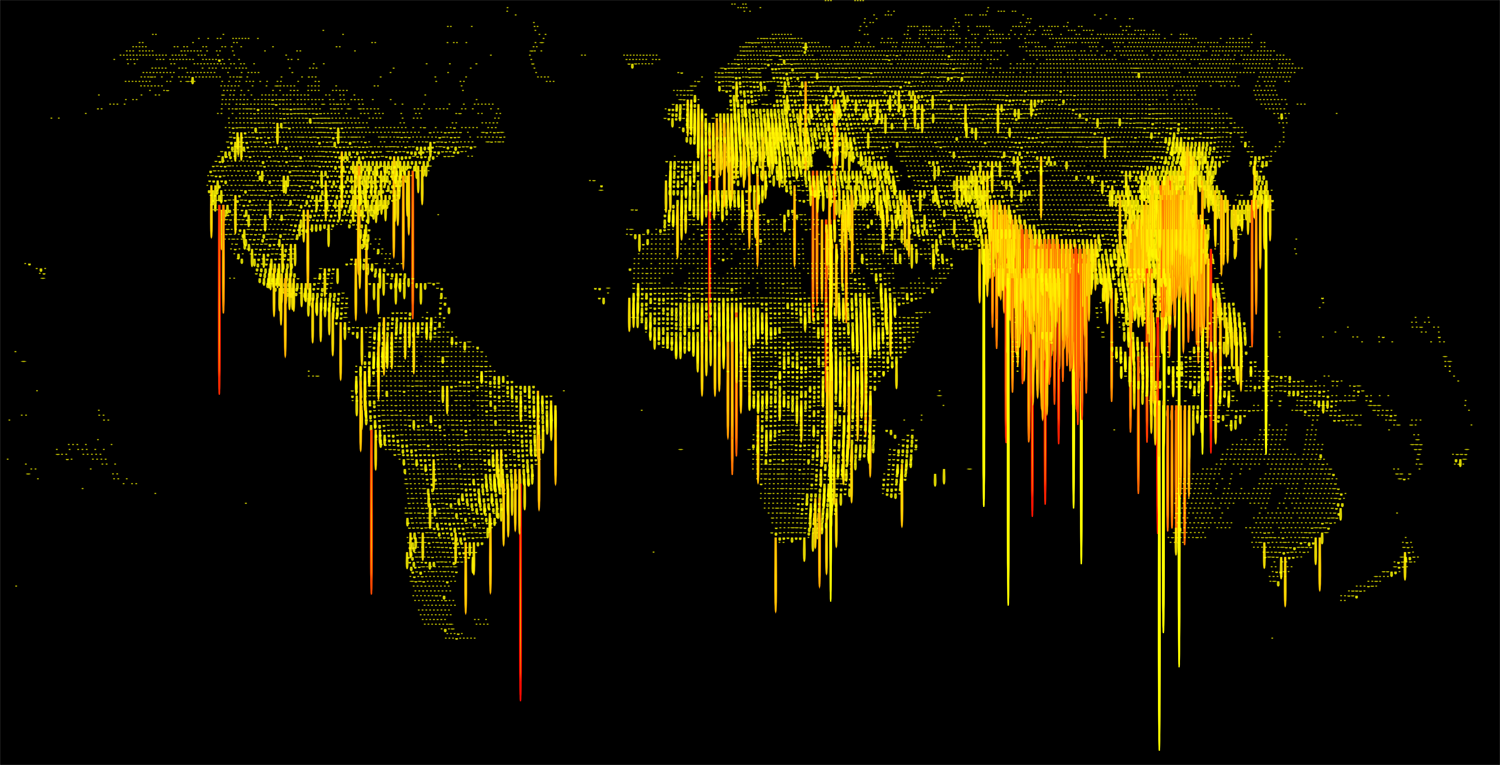

Economic growth also made the life expectancy go down. Europe was becoming more interconnected, trade increasing. This was partly due to innovations in banking (which had started in the 1100s), and partly, yes, the aftermath of the Black Death which caused a lot of economic change—not growth but change—some sectors growing, others shrinking, people moving around, people trying to stop people from moving around, markets shifting. There were also innovations in insurance, for example insuring your cargo ship so if it sinks you don’t go bankrupt like our Merchant of Venice. This meant more multi-region trade. For example, weaving wool into fine-quality non-itchy thread required a lot of oil, without which you could only make coarse, itchy thread. England produced lots of wool but no oil (except walnuts), so, in the Renaissance, entrepreneurs from England, instead of spinning low-profit itchy wool, started exporting their wool to Italy where abundant olive oil made it cheap to produce high-quality cloth and re-export it to England and elsewhere. This let merchants grow rich, prosperity for some, but when people move around more, diseases move more too. Cities were also growing denser, more manufacturing jobs and urban employment drawing people to crowd inside tight city walls, and urban spaces always have higher mortality rates than rural. Malaria, typhoid, dysentery, deadly influenza, measles, the classic pox, these old constants of Medieval life grew fiercer in the Renaissance, with more frequent outbreaks claiming more lives.

The Black Death contributed too—in school they talk as if the plague swept through in 1348 then went away, but the bubonic plague did not go away, it remained endemic, like influenza or chickenpox today, a fact of life. I have never read a full set of Renaissance letters which didn’t mention plague outbreaks and plague deaths, and Renaissance letters from mothers to their traveling sons regularly include, along with advice on etiquette and eating enough fennel, a list of which towns to avoid this season because there’s plague there. Carlo Cipolla (in the fascinating yet tediously titled Before the Industrial Revolution) collected great data for the two centuries after 1348, in which Venice had major plague bursts 7% of years, Florence 14% of years, Paris 9% of years, Barcelona 13% of years, and England (usually London) 22% in the earlier period spiking to 50% in the later 1500s, when England saw plague in 26 out of 50 years between 1543 and 1593. Excluding tiny villages with little traffic, losing a friend or sibling to plague was a universal experience from 1348 clear to the 1720s, when plague finally diminished in Europe, not because of any advance in medicine, but because fourteen generations of exposure gave natural selection time to work, those who survived to reproduce passing on a heightened immune response, a defensive adaptation bought over centuries by millions of deaths.

Today thousands of cases of Y. pestis (the plague bacterium) still occur each year, largely in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia where it was not endemic so immunities didn’t develop. And if geneticist Mihai Netea is correct that the immune mutation which helps those of European descent resist Y. pestis also causes our greater rate of autoimmune disorders, then the Black Death is still constantly claiming lives through the changes it worked into European DNA over 400 years (and literally causing me pain as I type this, as my own autoimmune condition flares). While the 1348 pandemic was Medieval, most of the Middle Ages did not have the plague—it’s the Renaissance which has the plague every single day as an apocalyptic lived reality.

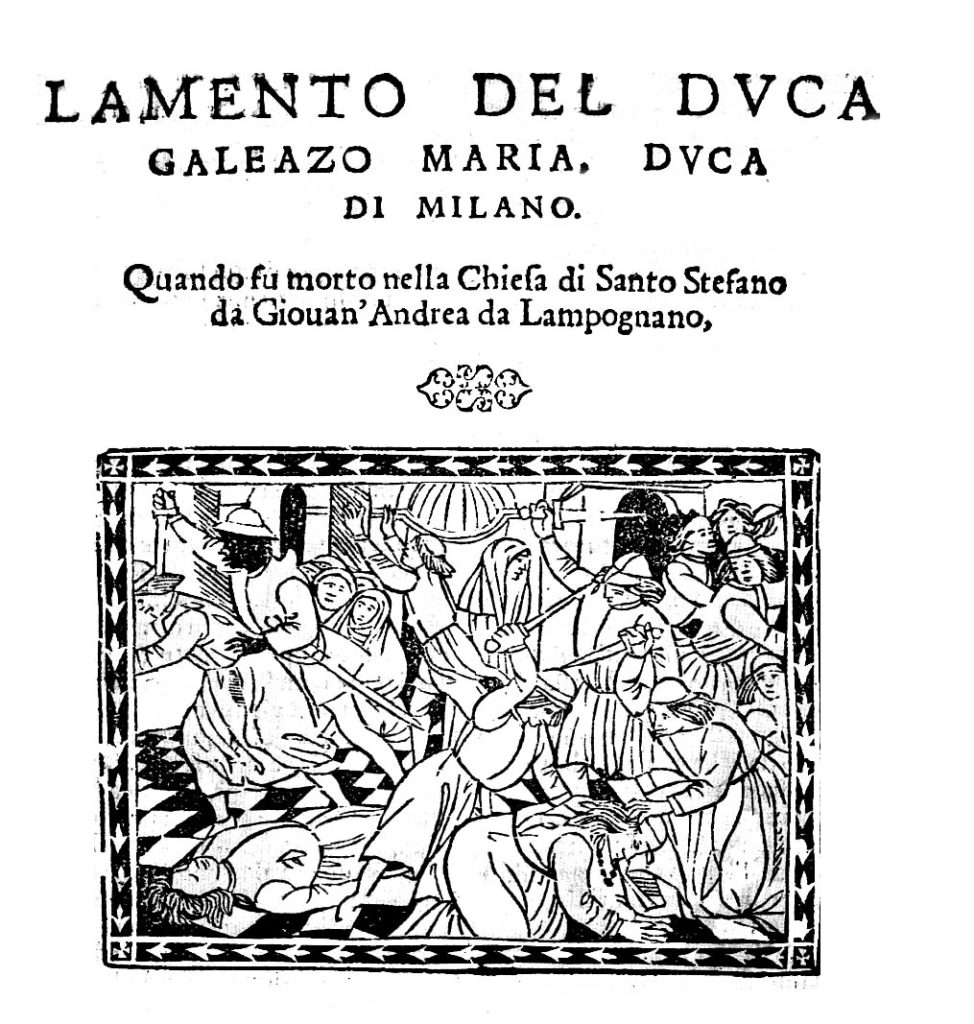

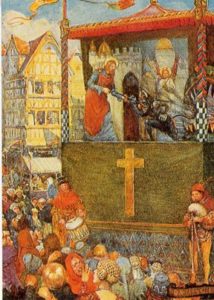

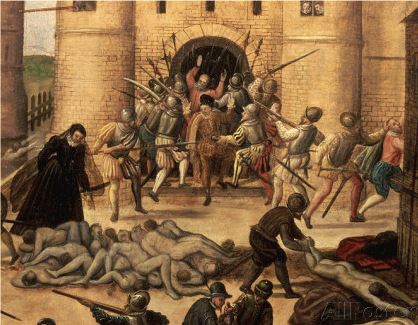

Economic growth also made non-military violence worse. Feuds (think Montagues and Capulets) were a Medieval constant, but the body count of a feud depends a lot on how wealthy the head families are, since the greater their wealth and the larger their patronage network, the larger the crowd of goons on stage in the opening scene of Romeo & Juliet when partisans of the two factions are biting their thumbs at each other, and the larger the number of unnamed men who also get killed in the background while Romeo fights Tybalt. In Italy especially, new avenues for economic growth (banking and mercenary work) quickly made families grow wealthy enough to raise forces far larger than the governments of their little city states, which made states powerless to stop the violence, and vulnerable to frequent, bloody coups. The Bentivoglios of Bologna and Sforza of Milan (whose marriage alliance produced Ercole who wrote that letter to Machiavelli) had risen by force, ruled by force, and were in turn overthrown by force, several times each, in fact, as rulers were killed, then avenged by returning sons or nephews, and cities flip-flopped between rival dynasties every few years:

In the 1400s most cities in Italy saw at least four violent regime changes, some of them as many as ten or twelve, commixed with bloody civil wars and factional massacres, until all Italy’s ruling houses were so new that the Knights Hospitaller—who normally required knights to have been noble four generations to join—let Italians in with only two generations because otherwise there would have been no one. Petrarch talked about this in his poem Italia Mia, which we think was written by 1347 (i.e. before the Black Death); he described Italy’s flesh covered with mortal wounds, caused by “cruel wars for light causes, and hearts, hardened and closed/ by proud, fierce Mars,” and his poor poem begging Italy’s proud, hard-hearted people for, “Peace, peace, peace.” It sounds just like what Ercole described to Machiavelli, doesn’t it? Well, Petrarch’s poem is as far from Machiavelli’s history as Napoleon’s rise from Yuri Gagarin’s space flight, a long time during which the wars grew worse, armies bigger, cities richer, plagues more frequent, steady escalation of the same things Petrarch feared would wipe out Italy 150 years before.

Important: none of this was new in the Renaissance! These were all gradual developments: banking, trade, centralization, the cultural produce of the Renaissance too (paintings, cathedrals, music, epics), these had all been gradually ramping up for centuries, changing the character of Europe decade by decade. Banking innovations started in the 1100s, insurance innovations in the 1300s, economic shifts before as well as after 1348, political shifts accumulated centuries, it’s all incremental. Thus, when I try to articulate the real difference between Renaissance and Medieval, I find myself thinking of the humorous story “Ever-So-Much-More-So” from Centerburg Tales (1951). A traveling peddler comes to town selling a powder called Ever-So-Much-More-So. If you sprinkle it on something, it enhances all its qualities good and bad. Sprinkle it on a comfy mattress and you get mattress paradise, but if it had a squeaky spring you’ll never sleep again for the noise. Sprinkle it on a radio and you’ll get better reception, but agonizing squeals when signal flares. Sprinkle it on the Middle Ages and you get the Renaissance. All key qualities were already there, good things as well as bad, poetry, art, currents of trade, thought, finance, law, and statecraft changing year by year, but add some Ever-So-Much-More-So and the intensity increases, birthing an era great and terrible. Many different changes reinforced each other, all in continuity with what came before, just higher magnitude, the fat end of a wedge of cheese, but it’s the same cheese on the thin end too. The line we draw—our slice across the cheese—we started drawing because people living in the Renaissance started to draw it, felt it was different, claimed it was different, and their claims reordered the way we think about history.

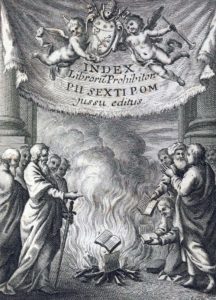

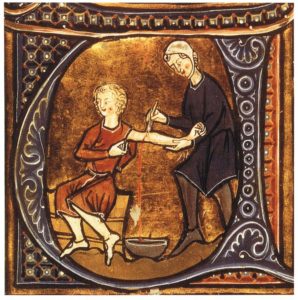

Some more quick un-fun facets of Renaissance life: while the Medieval Inquisition started in 1184, it didn’t ramp up its book burnings, censorship, and executions to a massive scale until the Spanish Inquisition in the 1470s and then the printing press and Martin Luther in the 1500s (Renaissance); similarly witchcraft persecution surges to scales unseen in the Middle Ages after the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum in 1486 (Renaissance); and the variety of ingenious tortures being used in prisons increased, rather than decreasing, over time. Rule of thumb: most of the scary practices we think of as “Medieval” were either equally true of the Renaissance, worse in the Renaissance, or only started in the Renaissance. If you want corrupt popes, they too can be more terrible as they get richer. And pre-sanitation, the more luxury goods traveled, the more people grew wealthy, the wider the variety of food people ate, and with more kinds of foods came more different kinds of parasites living in your intestines eating your from the inside out, hooray! Even in the Middle Ages we can tell your social class from the variety of parasite eggs in your preserved feces (the more you know!), but in the Renaissance the total could go up, and the frequency and intensity of chronic pain with it (not to mention a wider variety of horrible toxic things doctors would try to feed you as a cure; before sanitation more doctors = bad, not good).

Some more quick un-fun facets of Renaissance life: while the Medieval Inquisition started in 1184, it didn’t ramp up its book burnings, censorship, and executions to a massive scale until the Spanish Inquisition in the 1470s and then the printing press and Martin Luther in the 1500s (Renaissance); similarly witchcraft persecution surges to scales unseen in the Middle Ages after the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum in 1486 (Renaissance); and the variety of ingenious tortures being used in prisons increased, rather than decreasing, over time. Rule of thumb: most of the scary practices we think of as “Medieval” were either equally true of the Renaissance, worse in the Renaissance, or only started in the Renaissance. If you want corrupt popes, they too can be more terrible as they get richer. And pre-sanitation, the more luxury goods traveled, the more people grew wealthy, the wider the variety of food people ate, and with more kinds of foods came more different kinds of parasites living in your intestines eating your from the inside out, hooray! Even in the Middle Ages we can tell your social class from the variety of parasite eggs in your preserved feces (the more you know!), but in the Renaissance the total could go up, and the frequency and intensity of chronic pain with it (not to mention a wider variety of horrible toxic things doctors would try to feed you as a cure; before sanitation more doctors = bad, not good).

In sum, if you’re a time traveler and you’re being banished, don’t pick the Renaissance.

As for how an age so terrible to live through produced the masterpieces and innovations we still hold in awe, my ultrashort answer is that Renaissance art and culture was also a gradual ramp-up from ever-changing Medieval art and culture, and that the leaps we seem to see in the later period are the desperate measures of a desperate time.

Legitimacy is a key concept here. The secret we all know is that governments, countries, laws, they’re all just a bunch of stuff we made up. They exist only as long as we all keep agreeing they exist, and act accordingly. Far more than Tinkerbell, regimes and governments need us to believe in them or they die. Sometimes this death takes the form of people just ignoring old structures, like in the Hellenic age when a remote Greek colony might hear from the founding city so infrequently that it starts ignoring the empire and just makes its own government. A more common consequence when people stop believing in governments is that some rival will take advantage of that lack of confidence, and rise up to claim power instead, whether through an electoral primary challenge or a bloody civil war.

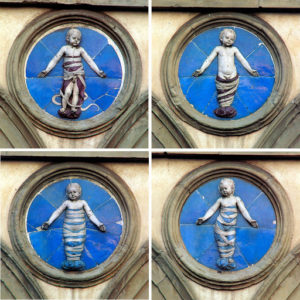

For this reason, regimes to work hard to gain legitimacy, that is to acquire any and all things that make people agree the regime is real, and has the right to rule. When a usurper murders the old king but marries his widow, sister, or daughter, that’s an attempt to secure legitimacy in a world where people are used to government going with blood right. When no local royal-blood bride is available, the usurper might instead marry a princess from a famous distant kingdom, and fill his court with expensive, exotic treasures and other indications that he’s connected to foreign powers and money—this is another bid at legitimacy since it implies the new ruler has strong allies and the means to bring prosperity and trade. There are lots of other ways to project legitimacy: getting trusted local elites to work for you, getting religious leaders to bless you, publishing your pedigree (fake or real) with mighty ancestors, cracking down on crime and having showy trials, paying an astrologer to circulate your horoscope with great predictions, mounting a big parade, building an equestrian statue of yourself in the square that everyone walks past, receiving ambassadors in a showy way so everyone sees how much foreign powers honor you, repairing bridges and caring for orphans so people talk about your generosity and virtue, even a modern city funding a zoo and orchestra and art museum is that city projecting legitimacy with the trappings we associated with cultured power. When a regime has lots of sources of legitimacy, it makes people more willing to go along with that regime continuing. Some sources of legitimacy tie into a culture’s traditional ideas about what makes power lawful (religion, heredity, virtue, particular values), while other sources of legitimacy, like a collection of exotic animals or a fancy palace, just impress people, and make them feel that life under this regime will probably be good, and that overthrowing it would probably be difficult if it has money to throw away on palaces and elephants.

For this reason, regimes to work hard to gain legitimacy, that is to acquire any and all things that make people agree the regime is real, and has the right to rule. When a usurper murders the old king but marries his widow, sister, or daughter, that’s an attempt to secure legitimacy in a world where people are used to government going with blood right. When no local royal-blood bride is available, the usurper might instead marry a princess from a famous distant kingdom, and fill his court with expensive, exotic treasures and other indications that he’s connected to foreign powers and money—this is another bid at legitimacy since it implies the new ruler has strong allies and the means to bring prosperity and trade. There are lots of other ways to project legitimacy: getting trusted local elites to work for you, getting religious leaders to bless you, publishing your pedigree (fake or real) with mighty ancestors, cracking down on crime and having showy trials, paying an astrologer to circulate your horoscope with great predictions, mounting a big parade, building an equestrian statue of yourself in the square that everyone walks past, receiving ambassadors in a showy way so everyone sees how much foreign powers honor you, repairing bridges and caring for orphans so people talk about your generosity and virtue, even a modern city funding a zoo and orchestra and art museum is that city projecting legitimacy with the trappings we associated with cultured power. When a regime has lots of sources of legitimacy, it makes people more willing to go along with that regime continuing. Some sources of legitimacy tie into a culture’s traditional ideas about what makes power lawful (religion, heredity, virtue, particular values), while other sources of legitimacy, like a collection of exotic animals or a fancy palace, just impress people, and make them feel that life under this regime will probably be good, and that overthrowing it would probably be difficult if it has money to throw away on palaces and elephants.

Thus the radical oversimplification is that, when times get desperate, those in power pour money into art, architecture, grandeur, even science, because such things can provide legitimacy and thus aid stability. Intimidating palaces, grand oratory, epics about the great deeds of a conqueror, expensive tutors so the prince and princess have rare skills like Greek and music, even a chemical treatise whose dedication praises the Duke of Such-and-such, these were all investments in legitimacy, not fruits of peace but symptoms of a desperate time. In an era when a book cost as much as a house (it really did!), and Florence’s Laurenziana library cost more per GDP than the Moon Landing, you don’t get that level of investment unless elites think they’re going to get something out of it. Just as today giant corporations fund charities or space tech because they get something out of it, publicity raising their stock prices, so a mighty merchant family might repair a church or build a grand public square and put their coat of arms on it, drawing investment and intimidating rivals.

Culture is a form of political competition—if war is politics by other means, culture is too, but lower risk. This too happened throughout the Middle Ages, but the Renaissance was ever-so-much-more-so in comparison, and whenever you get a combination of (A) increasing wealth and (B) increasing instability, that’s a recipe for (C) increasing art and innovation, not because people are at peace and have the leisure to do art, but because they’re desperate after three consecutive civil wars and hope they can avoid a fourth one if they can shore up the regime with a display of cultural grandeur. The fruits fill our museums and libraries, but they aren’t relics of an age of prosperous peace, they’re relics of a lived experience which was, as I said, terrible but great.

All this I’ll explore further in the book, but if you want more info in the meantime you can get an excellent overview of the period in Guido Ruggiero’s The Renaissance in Italy, and a look at how this fed philosophical innovation and birthed Renaissance humanism in James Hankins’s Virtue Politics. For today, though, our goal isn’t to look deeply at the David, it’s to look at the glitter we just scraped off it, and to understand where that glitter comes from.

Part 2: Where did the Myth Come From in the First Place? (A Renaissance Story)

Whenever I’m with Medievalists and the subject turns to one of the bad things people say about the Middle Ages (dark age, backwards, superstitious, stagnant, oppressive, enemy of progress, all homogenous), I make a point of speaking up and saying, “Yeah, that’s my guys’s fault. Sorry.” It was a joke the first time, and it’s still half a joke, but I keep doing it because there’s this special smile under the resulting chuckle, this pause, warming, affirming, on the Medievalist’s face that says: I’ve always felt I deserved an apology from the Renaissance! Thank you!

Because the beginning of the problem was the Renaissance’s fault.

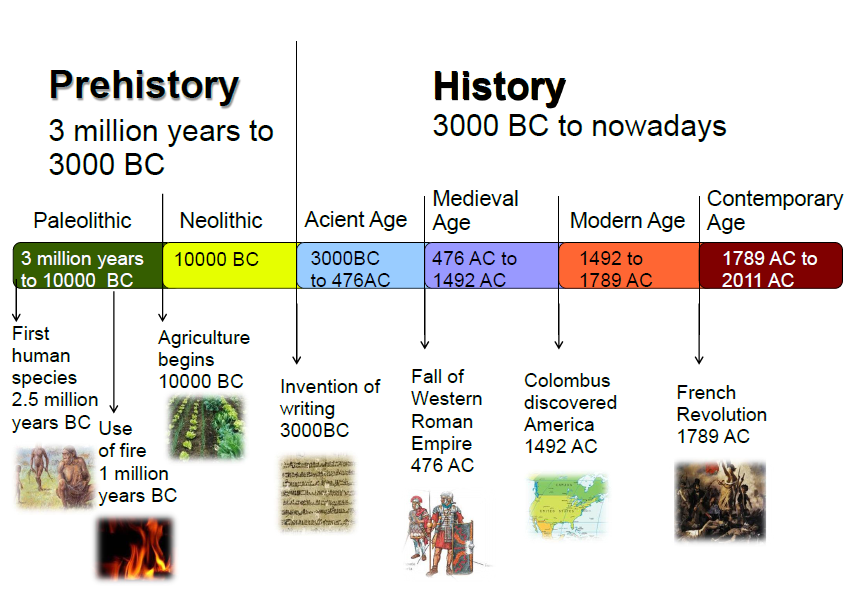

Pretty-much every culture, when it tells its history, divides it into parts somehow (reigns, eras, dynasties). These labels may not seem like a big deal, but they have a huge effect on how we imagine things. Think of how the discourse about boomers vs. Gen-X vs. millennials affects people’s self-identities, who associates with whom, and the kinds of discourse we can have with those terms that we couldn’t have with different ones. The lines and labels in our history are powerful. In my Terra Ignota science fiction novels I mention that the people in my 25th century society debate whether World War I ended in 1945 or 1989, and it always blows readers’ minds for a few seconds, and then follows the reflection: yeah, I could see WWI and WWII being considered one thing, like the Wars of the Roses. My first exposure to the way this makes your brain go *whfoooo* was as a kid and hearing Eugen Weber provocatively call WWI and WWII “The Second Thirty Years War”. Feels weird, right? Weird-powerful.

People living in the European and Mediterranean Middle Ages generally (oversimplification) divided history into two parts, BC and AD, before the birth of Jesus and after. For finer grain, you used reigns of emperors or kings, or special era names from your own region, i.e. before or after a particular event, rise, reign, or fall. There was also a range of traditions subdividing further, such as Augustine’s six ages of the world which divided up biblical eras (Adam to Noah, Noah to Abraham, etc.), though most of those subdivisions are pre-historical, without further subdivision post Christ’s Incarnation. The Middle Ages also had a sense of the Roman Empire as a phase in history, but it was tied in with the BC-to-AD tradition, and with ideas of Providence and a divine Plan. Rome had not only Christianized the Mediterranean and Europe through the conversion of Constantine c. 312 CE, but authors like Dante stressed how the Empire had been the legal authority which executed Christ, God’s tool in enacting the Plan, as vital to humanity’s salvation as the nails or the cross. Additionally, many Medieval interpreters viewed history itself as a didactic tool, designed by God for human moral education (not the discipline of history, the actual events). In this interpretation of history, God determined everything that happens, as the author of a story determines what happens. The events of the past and life were like the edifying pageant plays one saw at festivals: God the Scriptwriter introduces characters in turn—a king, a fool, a villain, a saint—and as we see their fates we learn valuable lessons about fickle Fortune, hypocrisy, the retribution that awaits the wicked, and the rewards beyond the trials and sufferings of the good. The Roman Empire had been sent onto the world’s stage just the same, a tool to teach humanity about power, authority, imperial majesty, law, justice, peace, offering a model of supreme power which people could use to imagine God’s power, and many other details excitedly explored by numerous Medieval interpreters. (Many Renaissance interpreters still view history this way, and the first who really doesn’t do it at all is Machiavelli.)

The two people most directly responsible for inventing the Middle Ages are two men from Tuscany: Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca, 1304-1374), and Leonardo Bruni (1370-1444).

Petrarch was the first person to talk about the era after the Roman empire as a separate, bad period of shadow, misery, darkness, and decay. Petrarch gained his fame with his Italian poetry, and popularized the sonnet (though we have a long time still to wait for Shakespeare), but later in his life he was part of a circle of Italian scholars who loved, loved, loved, loved Cicero, and read his political works intensively as they thought about questions of republicanism and statecraft. Petrarch described himself as having been born in exile. He was born in exile in space quite literally, while his parents were in banishment, and he grew up in Avignon in the period the papacy was there in French control. But he also considered himself an exile in time, exiled from that community of antiquity which was the true home of his spirit. I already quoted his lament Italia Mia, and his sense of the degeneration of his era was enhanced by the feeling that France’s control of the papacy had ravaged and spoiled Rome and Italy. He also lived through the Black Death, and lost almost all his scholar-friends in it. Two surviving friends wrote to him after the main wave had passed to plan a precious reunion—they were attacked by bandits on the way, and one murdered, while the other escaped but was missing for many months. You can understand why Petrarch, reading of the Pax Romana when the ancient texts claim you could walk in safety from one end of Rome’s empire to the other, might see his age as one of ash and shadow. He projected that ash and shadow back on everything since Rome, lumping together for the first time the long sequence we now refer to as the Middle Ages.

Petrarch, importantly, did not claim his era was already a golden age, nor did he use the word Renaissance; he claimed his era needed to have a transformation, that desperate times called for desperate measures, and that if Italy was to have any hope of healing it must look to its ancient past, to Rome, the Pax Romana, that dream age when there were no bandits on the road or pirates in the sea. The lost arts that nurtured the age of Emperors were languishing in ancient tomes waiting to be restored if only people reached for them. We know the Renaissance as the era that revived a lot of lost Roman technologies, geometry, engineering, large-scale bronze work, and those were important, but what Petrarch really thought would change things were people, intellectual technologies, not science or engineering tools. Petrarch wanted the library that educated Cicero, and Seneca, and Caesar. When we today look at ancient Rome we’re often struck most by the wicked Emperors, Caligula, Nero, the anecdotes of decadent corruption, but Petrarch instead saw the republican Brutus, who executed his own sons when they conspired to take over the state—in a world where city after city was falling to monarchal coups, and Lord Montague was used to using his great influence to make the Prince let Romeo get away with murder, the thought of Brutus putting Rome before his family felt like a miracle. (Unhelpfully, Petrarch didn’t write a single clear treatise where he spelled this out, but if you want a sample try his letters and invectives, or for the mega-thorough scholarly version see James Hankins’ Virtue Politics).

Important: even using antiquity wasn’t new in the Renaissance. Medieval people had been reading Seneca, and Cicero, and Virgil the whole time, and imitating and reusing ancient stuff, they just used the classics differently from how Petrarch did, just as the classics are also used differently in the 17th century, and the 19th century, and today. There were some major innovations in Renaissance engagement with the classics (several stages of innovation in fact), that differentiate them from Medieval, but those are complexities for another day.

Leonardo Bruni was the next step. He was child when Petrarch died, and grew up in the era of heady excitement of trying to use classical education to create the golden age Petrarch proposed. Bruni studied Latin with a focus (as Petrarch encouraged) on imitating ancient Latin instead of Medieval Latin whose grammar and vocabulary had evolved (as any language does) over the centuries. Bruni served as Chancellor of Florence, and imitated ancient Roman historians in writing his History of the Florentine People, which for the first time formally divided history into three parts: ancient, middle, and modern, which we now call Renaissance. He also filled his history with analysis and deep interpretation, which many Renaissance scholars will tell you was the first modern history, the first history of a post-classical time/place, and the first truly analytic history written since antiquity, and then Medievalists will scream at them and pile up examples of Medieval chronicles full of framing and moral analysis, which absolutely are doing sophisticated interpretive work, and vary enormously from each other, but Bruni’s is recognizably as different. Why? Largely because Bruni actively wanted his history to seem innovative and different, and wrote with that as a goal, in a new kind of Latin, with new structure, setting out to make something everyone would look at and say: Wow, it’s like what the Romans did!

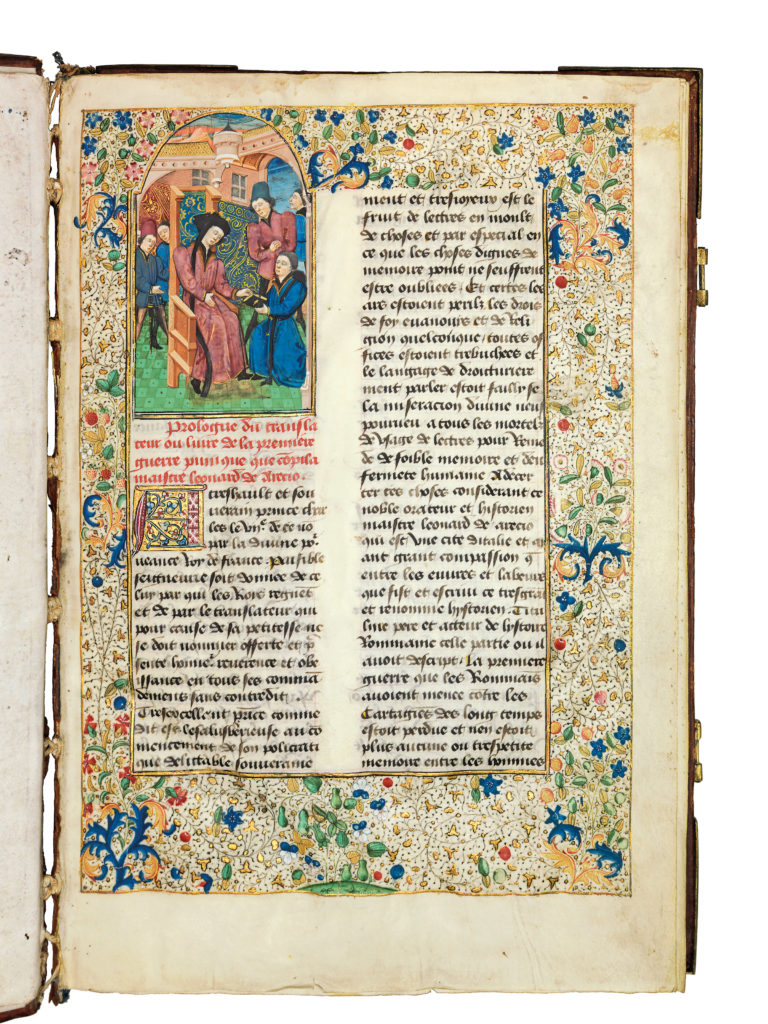

With Bruni we had three periods—ancient, medieval, and the new age. That new age wasn’t called rinascita until Vasari’s Lives of the Artists in 1550 (more than a century after Bruni) and renaissance proper was coined by Jules Michelet in 1855, but Bruni’s idea of three periods, and that this new one could be a golden age, caught on quickly because of its potential for… (da da da daaa!) …legitimacy! Back then, as now, claiming that you’re the start of a new golden age is an ideal way to make your (teetering, illegitimate) regime seem exciting, full of momentum, glorious. History-writing modeled on Bruni quickly became all the rage, and you could awe people with a history of how great your city/people/family is, get them excited about a golden age, make yourself seem legitimate. And Bruni’s history writing had another power too.

One set of events Bruni described in his Florentine History were the conquests of Gian Galeazzo Visconti the “Viper of Milan” (1351-1402), a man who lived up in every way to his badass family crest of a serpent swallowing a helpless little dude. After ambushing and supplanting his uncle, the Viper seized Milan (bribing appropriate powers to make him duke), then took Verona, Vicenza, Padua, and tried for all of northern Italy including Bologna and Florence, securing a great victory at the Battle of Casalecchio in 1402. But then (according to Bruni) brilliant Florentine cunning arranged the would-be conqueror’s defeat and downfall. When Bruni’s history circulated in 1444, the Viper’s grandson Duke Filippo Maria Visconti did a spit take: “What the?! We didn’t lose that war! Granddad dropped dead of a f*ing fever and the troops had to go home! The Florentines never beat us in a single battle! They can’t say won the war!” They can. They did.

It turns out history isn’t written by the winners; history is written by the people who write histories.

So, what are you going to do about it, grandson of the Viper of Milan? There’s only one thing to do: hire one of these new classically-educated humanisty types to write a history of your city and your family framed your way, and replacing the murdered-his-uncle bribed-the-king totally-illegitimate conquest-by-force narrative with a glorious lineage that constantly kicked Florence’s ass!! That’s what he did—that’s what everybody did, Milan, Venice, France, England, Hungary, Naples; everybody had to have a history, and all the histories claimed there had been a bad middle age, that it was over, and that we were now in the glorious classical-revival-powered new age which had the potential to surpass it thanks to the virtues and glories of [Insert Prince Here]. This is why, up in England, baby King Henry VI’s uncle Duke Humphrey of Gloucester tried to hire Leonardo Bruni to come to England and work for him, and write a history that would shore up the tenuous Lancastrian claim to the throne (we’re entering the Wars of the Roses here). And this is why, while Bruni stayed in Florence, another major Florentine figure Poggio Bracciolini actually was lured by the high pay to go to England and work for Humphrey’s rival Cardinal Beaufort. And all these histories pick and choose details to make the current regime/ruler look great and legitimate, at the expense of making the newly-invented middle age look bad.

This is why all Medievalists, deep down inside, know they deserve an apology from the Renaissance.

One attempt at a solution is dropping the term Renaissance, but that doesn’t actually solve the problem, since it leaves us with antiquity and a period from then to… what? Is the dividing line the Enlightenment? Industrialization? Colonialism? The Industrial Revolution? The Agricultural Revolution? The French Revolution? WWI? No matter how late you push the line, any of these divisions is still accepting Bruni’s ancient-middle-modern division, and involves making a claim about what begins the modern. Normal parlance in history now is “early modern” which begins with [insert-scholarly-squabble-here] and ends roughly with the French Revolution, which is generally agreed to kick off “modern” proper. While “early modern” does avoid accepting claim that the Middle Ages were bad and needed a rebirth, and I use it myself, I also think it’s a dreadful term, since (A) it’s confusing (“early modern” sounds like the Crystal Palace, not Shakespeare’s Globe), and (B) the term actively worsens the degree to which your selected start date is a judgment call about what makes us modern. Because the real problem with the myth of the bad Middle Ages versus golden Renaissance is not what Petrarch and Bruni created within the Renaissance itself—it’s what happened later to entangle both terms with an equally problematic third term: modern.

Part 3: Why is the Myth of a Renaissance Golden Age Retold so Much? (a post-Renaissance story)

The thing about golden ages—and this is precisely what Petrarch and Bruni tapped into—is that they’re incredibly useful to later regimes and peoples who want to make glorifying claims about themselves. If you present yourself, your movement, your epoch, as similar to a golden age, as the return of a golden age, as the successor to a golden age, those claims are immensely effective in making you seem important, powerful, trustworthy. Legitimate.

The thing about golden ages—and this is precisely what Petrarch and Bruni tapped into—is that they’re incredibly useful to later regimes and peoples who want to make glorifying claims about themselves. If you present yourself, your movement, your epoch, as similar to a golden age, as the return of a golden age, as the successor to a golden age, those claims are immensely effective in making you seem important, powerful, trustworthy. Legitimate.

In sum, one of the most powerful tools for legitimacy is invoking a past golden age. Under my rule we will be great like X was great! Whether it’s a giant golden age (Rooooome!) or a tiny golden age (the US 1950s!), if you can claim to be bringing it back, you can make a very clear, appealing case for why you should have power. This claim can be made by a king, a duke, a ruling council, a political party, an individual, or a whole movement. It can be made explicitly in rhetoric (I am the new Napoleon!) or implicitly by borrowing the decorative motifs, vocabulary, and trappings of an era. An investment banking service that uses a Roman coin profile as its logo, names its different mutual funds after Roman legions, and has a pediment and columns on its corporate headquarters is trying to project legitimacy from the idea of antiquity as a golden age of power and stability.

The newborn United States of America when it decided to make the Washington Monument be a giant obelisk, that was another bid at legitimacy and projecting power by invoking the golden ages of ancient Egypt and conquering Rome, combined in the Washington Monument’s case with other things like, instead of the traditional gold tip on top, using high-tech more-expensive-than-gold aluminum, mixing golden age with power claims about wealth and science.

So…

…because the Renaissance had called itself a golden age, by the 17th century it had joined the list of epochs that you can invoke to gain legitimacy, and has been invoked that way many times. This is why 18th and especially 19th and earlier 20th century governments and elites raced to buy up Italian Renaissance art treasures and display them in their homes and museums. This is why Mussolini, while he mostly invoked imperial Rome, used the Renaissance too, and even made special arrangements to meet Hitler inside the Vasari Corridor in Florence to show off the art treasures of the Uffizi. And this is why the US Library of Congress building is painted all over inside with imitations of Renaissance classicizing frescos and allegorical figures in Renaissance style even though the quotations they include and values they celebrate are largely not Renaissance.

One consequence of golden ages being so powerful is that powers squabble over them: “I’m the true successor of [XXX]!” “No, I’m the true successor!” You see this in the fascinating modern day dispute over the name Macedonia in which both Greece and the country now called North Macedonia both want to be seen as the land of Alexander the Great, and argued over the name tooth and nail, dragging in both the UN and NATO. Since golden ages are mythical constructions (the events are real but the golden age-ness is mythmaking) they’re easy to redefine to serve claims of true successor status—all you have to do is claim that the true heart that made the golden age great was X, and the true spirit of X flourishes most in you. Any place (past or present) that calls itself a new Jerusalem, new Rome, or new Athens is doing this, usually accompanied by a narrative about how the original has been ruined by something: “Greece today is stifled by [insert flaw here: conquest, superstition, socialism, lack of socialism, a backwards Church, whatever], but the true spirit of Plato, Socrates and the Examined Life flourish in [Whateverplace]!”

Ancient Rome is particularly easy to use this way because Rome had several phases (republic, empire, Christian Rome) so if some rival has done a great job declaring itself the New Roman Empire you can follow up by saying the Empire was the corrupt decadent period and the Roman Republic was the true Rome! Simply quote Cicero and talk about wicked emperors and you can appropriate the good Rome and characterize your rivals as the bad Rome. If republic, empire, and Christian Rome are all claimed, you can do something more creative like the 19th century romantic movement which claimed the archaic pastoral Rome of Virgil’s Georgics, replacing pediments and legionary eagles with garlands and shepherds and claiming a mythic golden age no one had been using lately.

The same is true of claiming Renaissance. If you can make a claim about what made the Renaissance a golden age, and claim that you are the true successor of that feature of the Renaissance, then you can claim the Renaissance as a whole. This is made easier by the fact that “the Renaissance” is incredibly vague. When did it start? 1400? 1350? 1500? 1250? 1550? 1348? When did it end? 1600? 1650? 1700? You can find all these dates if you dig through books about “the Renaissance” written in different countries and different fields (art history, literary history). I pointed out that Petrarch’s Italia Mia is as far from Ercole’s Bentivoglio’s letter to Machiavelli as Napoleon’s rise from Yuri Gagarin’s space flight, but even at Machiavelli we’re still only half-way through the large, vague period that different people label Renaissance. On my own university campus, if I drop by different departments and ask colleagues when Renaissance begins, I get 1200 or 1250 from the Italian lit department (some of whom say Machiavelli is already “modern”), but in the English building I might get 1450 or even 1500. I think drawing a line after Black Death makes sense for Italy at least, or maybe at 1400, but there are plenty of counter-arguments, and people on campus who identify as Medievalists who study things later than some things I work on. I think it’s great for Medieval and Renaissance to overlap, since I—looking mainly forward—ask different questions about someone like Petrarch from the questions my Medievalist colleagues ask. The only “wrong” answer to where the line falls, in my opinion, is to believe there is a clear line.

And if we zoom into this long, vague period, when was the “high Renaissance” i.e. the best part, the most characteristic part? If you ask a political scientist it’s usually the very early 1400s, when Bruni and other innovative political thinkers were writing; if you ask an art historian it’s the decades right after 1500 when ¾ of the Ninja Turtles overlapped; if you ask a theater scholar it’s Shakespeare who was born fully 200 years later than Bruni and his peers discussing politics. It all depends on what you think defines the Renaissance, so if you have a different focus then different dates feel like periphery or core.

And if we zoom into this long, vague period, when was the “high Renaissance” i.e. the best part, the most characteristic part? If you ask a political scientist it’s usually the very early 1400s, when Bruni and other innovative political thinkers were writing; if you ask an art historian it’s the decades right after 1500 when ¾ of the Ninja Turtles overlapped; if you ask a theater scholar it’s Shakespeare who was born fully 200 years later than Bruni and his peers discussing politics. It all depends on what you think defines the Renaissance, so if you have a different focus then different dates feel like periphery or core.

So, just as when we invoke Rome we can pick republican Rome, imperial Rome, pastoral Rome, Christian Rome, the conquering Rome of Julius Caesar or the peaceful Rome of the Pax Romana, similarly there are a huge range of Renaissances one can invoke: Bruni’s, Raphael’s, Machiavelli’s, Luther’s, Shakespeare’s. But choosing your Renaissance is an especially potent question because of… (drumroll please)… the X-Factor.

Okay, deep breath.

After the Renaissance, in the period vaguely from 1700 to 1850, everyone in Europe agreed the Renaissance had been a golden age of art, music, and literature specifically. Any nation that wanted to be seen as powerful had to have a national gallery showing off Renaissance (mainly Italian) art treasures, and capital buildings with Renaissance neoclassical motifs, while an individual with elite ambitions had to know classicizing Latin, and a bit of Greek, and have opinions about Raphael, Titian, Petrarch, and the polyphonic motets of Lassus. Seriously: in the original Doyle Holmes stories, so 1850-1910, after having Watson establish Holmes’s “Knowledge of literature—nil. Philosophy—nil.” still has Holmes carry a pocket Petrarch and write a monograph on the polyphonic motets of Lassus, because that’s what a smart, impressive person did in 1850. This also meant that Renaissance art treasures were protected and preserved more than Medieval ones—if you’re valorizing the Renaissance you’re usually criticizing the Middle Ages in contrast, so these generations learned to think of Renaissance art as good taste and the periods on both sides (Medieval and baroque) as bad taste, and a lot of great Medieval art was left to gather dust, or rot, or was even actively destroyed, since nothing invokes the Renaissance like sweeping away the “bad” medieval. As a result, the Renaissance became a self-fulfilling source base: go to a museum today and you see much more splendid Renaissance art than Medieval, leading to the natural conclusion that the Renaissance produced more art in general, but Middle Ages did make splendid art, it’s just that later centuries didn’t preserve it as carefully, so less survives, and what survives is more likely to be in storage than in the main gallery.

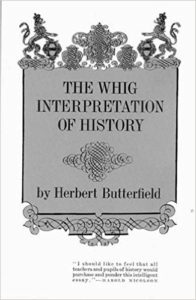

The transition from people being excited about Renaissance art and culture to being excited about the Renaissance as an era came in the mid-1800s, primarily with the work of Swiss historian Jacob Burkhardt, and his 1869 The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. It’s a gorgeous read, unskimmably rich prose, and Burkhardt’s work was a major breakthrough moment for the practice of history as a whole, because he showed how you could write a history, not of a country or a person, but of a culture, discussing the practices and ideas of an era, examining art and artists side-by-side with authors, soldiers, and statesmen as examples of people of a period and the way they thought, acted, and lived. The book pioneered cultural history, the practice of trying to study societies and their characteristics, acknowledging the interrelationship of politics with art and culture instead of examining them separately. Cultural history remains a major field, and one where some of the best work on once-neglected topics like women, pop culture, and non-elites has flourished. But…

The transition from people being excited about Renaissance art and culture to being excited about the Renaissance as an era came in the mid-1800s, primarily with the work of Swiss historian Jacob Burkhardt, and his 1869 The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. It’s a gorgeous read, unskimmably rich prose, and Burkhardt’s work was a major breakthrough moment for the practice of history as a whole, because he showed how you could write a history, not of a country or a person, but of a culture, discussing the practices and ideas of an era, examining art and artists side-by-side with authors, soldiers, and statesmen as examples of people of a period and the way they thought, acted, and lived. The book pioneered cultural history, the practice of trying to study societies and their characteristics, acknowledging the interrelationship of politics with art and culture instead of examining them separately. Cultural history remains a major field, and one where some of the best work on once-neglected topics like women, pop culture, and non-elites has flourished. But…

Burkhardt was also the main figure who popularized the terms “modernity” and “modern.” He argued that the Renaissance was the birth of “modern man,” and that modern man was defined by a powerful sense of human excellence and human potential. According to Burkhardt, the core of this change—the spirit of the Renaissance which sparked the triumphant path of progress toward modernity—was the rise of individualism. As he says in the beginning of Part II:

In the Middle Ages both sides of human consciousness—that which was turned within as that which was turned without—lay dreaming or half awake beneath a common veil. The veil was woven of faith, illusion, and childish prepossession, through which the world and history were seen clad in strange hues. Man was conscious of himself only as member of a race, people, party, family, or corporation—only through some general category. In Italy this veil first melted into air; an objective treatment and consideration of the state and of all the things of this world became possible. The subjective side at the same time asserted itself with corresponding emphasis; man became a spiritual individual, and recognized himself as such.

The Medievalists reading this are gnashing their teeth, and yes, this moment is core to the persistence of the myth of the bad, backward, stagnant, sleepy middle ages, and equally core to the myth of the Renaissance Man: awake, ambitious, aware of his own power, rational, ripping through the cobwebs of superstition, desirous of remaking the world but also of intentionally fashioning him or herself into something splendid and excellent. A human being who realizes human beings can be their own masterpieces.

In the mid-19th-century, when Burkhardt wrote, Europe was very enamored of individualism, of new democratic ideas of government, of nationalism and ideas of individual consciousness and national consciousness, and of the notions of genius, both genius individuals and the geniuses of peoples. Thus, Burkhardt’s claim that the Renaissance was born from individualism gave all sorts of 19th century movements the ability to claim the Renaissance golden age as an ancestor. Germany, Britain, the young United States, despite having little to do with Italy, they could all claim to be the true inheritors of Renaissance greatness if they could claim that individualism and the opportunity to be a self-made man prospered more truly among their peoples than in Italy.

In the mid-19th-century, when Burkhardt wrote, Europe was very enamored of individualism, of new democratic ideas of government, of nationalism and ideas of individual consciousness and national consciousness, and of the notions of genius, both genius individuals and the geniuses of peoples. Thus, Burkhardt’s claim that the Renaissance was born from individualism gave all sorts of 19th century movements the ability to claim the Renaissance golden age as an ancestor. Germany, Britain, the young United States, despite having little to do with Italy, they could all claim to be the true inheritors of Renaissance greatness if they could claim that individualism and the opportunity to be a self-made man prospered more truly among their peoples than in Italy.

But there was more: by claiming that the Renaissance—and all its glittering art and innovation—was caused by individualism, Burkhardt was really advancing a claim about the nature of modernity. Individualism was an X-Factor which had appeared and made a slumbering world begin to move, sparking the step-by-step advance that led humanity from stagnant Medieval mud huts to towers of glass and iron—and by implication it would also define our path forward to an even more glorious future. In other words, the X-Factor that sparked the Renaissance was the defining spirit of modernity. If individualism was responsible, not only for the Renaissance, but for the wonders of modernity, then logically those regimes of Burkhardt’s day which most facilitated the expression of individualism could claim to be the heart of human progress and to hold the keys to the future; those nations which did not advance individualism (where socialism prospered, for example, or “collectivism” which was how 19th century Europe characterized most non-Western societies) were still the slumbering Middle Ages, in need of being awakened to their true potential by those nations which did possess the X-Factor of human progress.

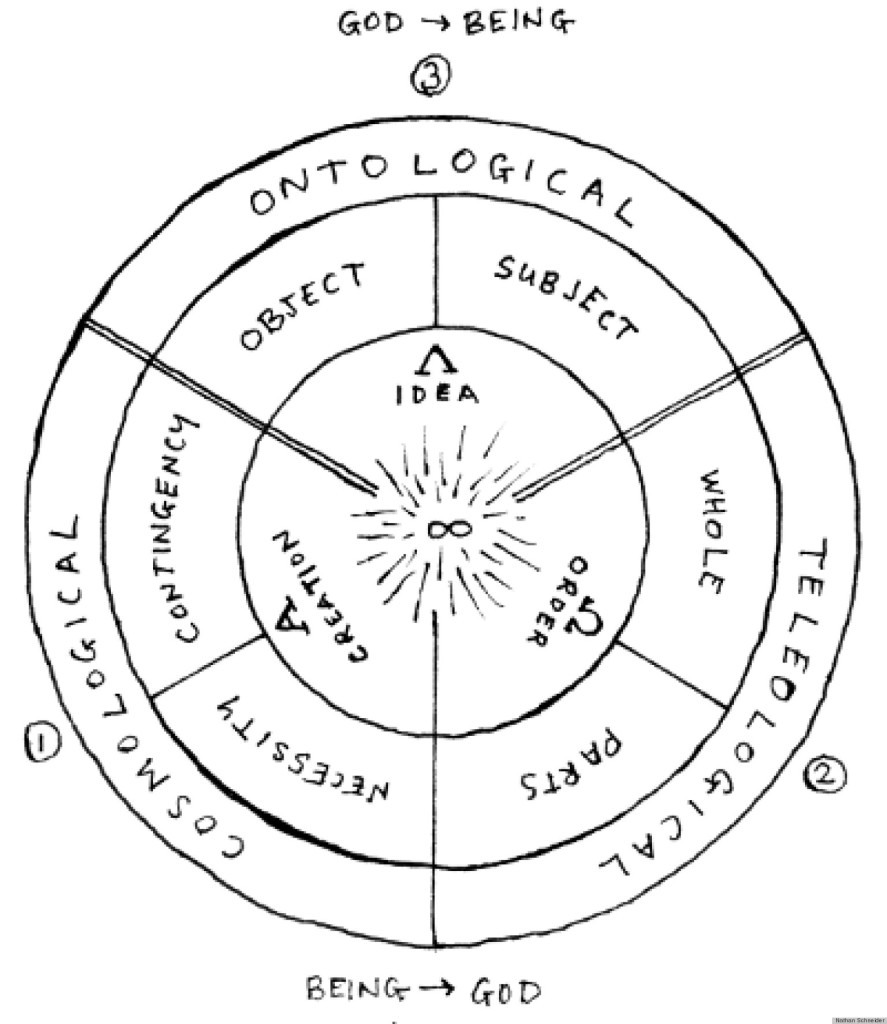

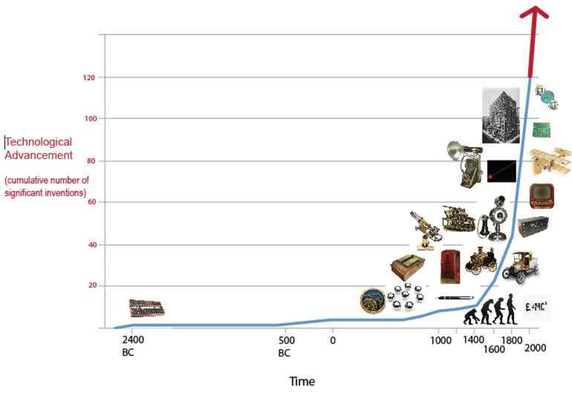

I hope you winced a few times in the previous paragraph, recognizing toxic 19th century problems (eurocentrism, orientalism, “White Man’s Burden” thinking), as well as basic historical errors (spoiler: you can find plenty of individualism in Medieval texts, and lots of things that are absolutely not individualism in Renaissance ones). But those specifics aren’t the big problem. The big problem was how entrancing the idea of an X-Factor was, the notion that there is one true innovative spirit which defines both Renaissance and modern, and advances in a grand and exponential curve from Petrarch through Leonardo and Machiavelli on to [insert modern hero here]. Thus Burkhardt birthed what I call the quest for the Renaissance X-Factor. Because when the first scholars disagreed with Burkhardt, they didn’t objcet to the idea that the Renaissance was caused by a great defining X-Factor, they loved that idea, they simply argued about what exactly the X-Factor was.

I hope you winced a few times in the previous paragraph, recognizing toxic 19th century problems (eurocentrism, orientalism, “White Man’s Burden” thinking), as well as basic historical errors (spoiler: you can find plenty of individualism in Medieval texts, and lots of things that are absolutely not individualism in Renaissance ones). But those specifics aren’t the big problem. The big problem was how entrancing the idea of an X-Factor was, the notion that there is one true innovative spirit which defines both Renaissance and modern, and advances in a grand and exponential curve from Petrarch through Leonardo and Machiavelli on to [insert modern hero here]. Thus Burkhardt birthed what I call the quest for the Renaissance X-Factor. Because when the first scholars disagreed with Burkhardt, they didn’t objcet to the idea that the Renaissance was caused by a great defining X-Factor, they loved that idea, they simply argued about what exactly the X-Factor was.

Thanks to Burkhardt, the Renaissance came to be defined as the period after Medieval but before Enlightenment when something changed and pushed things toward modernity—the moment that the defining spirit of modernity appeared. From that point on, claiming you were the successor to the Renaissance didn’t just mean claiming a golden age like Rome, it let you also claim that modernity itself was somehow especially yours. If you could argue that the reason the Renaissance was great was that it did the thing you do, then you are the heart of modernity and progress, even of the future, while those who don’t celebrate that spirit are the enemies of progress. Thus every time someone proposed a new X-Factor, a different explanation for what made Renaissance different from Medieval, that made it possible to make new claims about the nature of modernity, and which nations or movements have it right. This model even lets one claim the future: the X-Factor was born in the Renaissance, grew in the Enlightenment and in modernity, and is the key to unlocking the next glorious age of human history as it unlocked both Renaissance and modern. This lets you advance teleological arguments about the inevitable triumph of [democracy, nationalism, atheism, capitalism, whatever]. It’s a version of history that’s not only legitimizing but comforting, since it lets you feel you know where history is headed, what will happen, who will win.

To give specific examples, if we’re in the middle of the Cold War, and an influential historian publishes a book arguing that the X-Factor that sparked the Renaissance was double-entry bookkeeping, i.e. the rise of banking and the merchant class, America can say: “The Renaissance X-Factor was the birth of capitalism! The fact that it was a golden age proves capitalism will make a golden age too, and the true successor of this golden age is our alliance of modern capitalist regimes!” If, on the other hand, we’re in a nationalist wave, say in 1848 or 1920, and someone argues that the X-Factor that sparked the Renaissance was the call for national unity articulated in Petrarch’s Italia Mia or Savonarola’s sermons (this is Pasquale Villari), and that what ended the Renaissance golden age was when Italy was conquered and divvied up among the Bourbons and Hapsburgs, then the Renaissance can be claimed as a predecessor by the Italian unification movement, the German unification movement, any nationalist movement anywhere can claim that uniting peoples into nations is what drives modernity. If we claim the Renaissance was birthed by the rise of secular thought, that Renaissance geniuses were the first people to break through the bonds of superstition, and that Leonardo and Machiavelli were secret atheists (this is Auguste Comte), then we can claim that secularization and the secular state is the heart of human progress and modernity. And if someone claims the X-factor was republican proto-democratic thought, the political writings and discourse of civic participation unique to the Italian city republics, Florence, Venice (this is Hans Baron), then we can claim that republican democracy is the key to human progress, that modern democracies are the heart of modernity, and everything else is backwards, outside, Medieval, bad, and needs to be replaced.

To this day, every time someone proposes a new X-Factor for the Renaissance—even if it’s a well-researched and plausible suggestion—it immediately gets appropriated by a wave of people & powers who want to claim they are the torch-bearers of that great light that makes the human spirit modern. And every time someone invokes a Renaissance X-Factor, the corresponding myth of the bad Middle Ages becomes newly useful as a way to smear rivals and enemies. As a result, for 160 years and counting, an endless stream of people, kingdoms, political parties, art movements, tech firms, banks, all sorts of powers have gained legitimacy by retelling the myth of the bad Middle Ages and golden Renaissance, with their preferred X-Factor glittering at its heart.

To this day, every time someone proposes a new X-Factor for the Renaissance—even if it’s a well-researched and plausible suggestion—it immediately gets appropriated by a wave of people & powers who want to claim they are the torch-bearers of that great light that makes the human spirit modern. And every time someone invokes a Renaissance X-Factor, the corresponding myth of the bad Middle Ages becomes newly useful as a way to smear rivals and enemies. As a result, for 160 years and counting, an endless stream of people, kingdoms, political parties, art movements, tech firms, banks, all sorts of powers have gained legitimacy by retelling the myth of the bad Middle Ages and golden Renaissance, with their preferred X-Factor glittering at its heart.

We scholars do our best to battle this, to introduce a complex and un-modern Renaissance, but the very usefulness of the myth guarantees that it will be repeated much more broadly than our no-fun efforts to correct it. A lot of Renaissance historians today reject the idea of a single X-Factor and try instead to talk about combinations of mixing factors. Many of us also try to argue that the Renaissance was not fundamentally modern, that it was its own distinctly un-modern thing. But it’s a hard sell, because the narrative of a special spirit launching us from Petrarch to the Moon Landing is enchanting, and because a complicated, messy, un-modern Renaissance snatches away the golden Renaissances most people meet first. Nobody in this century has read about the French Invasion of 1494, or even about the Guelphs and Ghibellines, before meeting the genius cults of Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Scraping the glitter off to reveal the imperfect and violent David underneath is an assault on our understandings of our past and present, on what it means to be ourselves, even on our sense of where the future is heading. People find that unsettling. And people who look to Renaissance celebrities as role models and intellectual ancestors don’t like to hear about their rough un-modern sides. So people get hostile, or unsettled, they keep telling the myths, and use cherry picked sources to glob the glitter-paint back on. It’s not always done in bad faith—if from early childhood you’ve always learned the Renaissance was sparkling and golden, and you see a bare patch where the glitter has come off, of course you’ll think that bare patch is the error, that the still-sparkly parts are the real thing. You treat the oddball patch as damage, and keep believing what that documentary or museum label told you years ago when you saw your first Renaissance masterpiece and fell in love. So the myth persists, and for every attempt to correct it we’re up against a dozen tour guide scripts, and TV specials, and corporate statements, and outdated textbooks, and new books (fiction and nonfiction alike) that glob the glitter on. So you can understand why, from time to time, Renaissance and Medieval specialists alike just have to stop and scream like Sisyphus.

Conclusion: We Should Aim for Something Better than the Renaissance

This, in not-very-brief, is why we keep telling the myth of the golden Renaissance, and bad Middle Ages.

Now, let’s look again at our other starting question: “If the Black Death caused the Renaissance will the COVID pandemic cause a golden age?” You see the problems with the question now: the Black Death didn’t cause the Renaissance, not by itself, and the Renaissance was not a golden age, at least not the kind that you would want to live in, or to see your children live in. But I do think that both Black Death and Renaissance are useful for us to look at now, not as a window on what will happen if we sit back and let the gears of history grind, but as a window on how vital action is.

The Black Death first: it didn’t cause the Renaissance, no one thing caused the Renaissance, it was a conjunction of many gradual and complicated changes accumulating over centuries (banking, legal reform, centralization of power, urbanization, technology, trade) which came together to make an age like the Medieval but ever-so-much-more-so. The idea that the Black Death caused a prosperity boom comes from old studies which showed that wages went way up after the Black Death, creating new possibilities for laborers to gain in wealth and rise in status (like the golden 1950s). But those were small studies from a few places (mainly bits of England), and we have newer studies now that show that wages only rose in a few places, that in other places wages didn’t rise, or actually went down, or that they started to rise but elites cracked down with new laws to control labor, creating (among other things) the first workhouses, laws limiting freedom of movement, and other new forms of unfreedom and control. What the Black Death really caused was change. It caused regime changes, instability letting some monarchies or oligarchies rise, or fall. It caused policy and legal changes, some oppressive, some liberating. And it caused economic changes, some regions or markets collapsing, and others growing.

If you really want to know what COVID will do, I think the place to look is not Renaissance Italy, but the Viking settlements in Greenland, which vanished around 1410. Did they all die of the plague? No. We’re pretty sure they never got the plague, they were too isolated. But the Greenland settlements’ economy had long depended on the walrus trade: they hunted walruses and sold the ivory and skins, and ships would come from Norway or Iceland to trade for walrus, bringing goods one couldn’t make in Greenland, like iron, or fine fabric, or wheat. But after 1348 the bottom dropped out of the walrus market, and the trading ships stopped coming. By 1400 no ships had visited Greenland for years except the few that were blown off-course by storm. And meanwhile there were labor shortages and vacant farms on the once-crowded mainland. So we think the Greenland Vikings emigrated, asked those stray ships to take them with them back to Europe, as many as could fit, abandoning one life to start another. That’s what we’ll see with COVID: collapse and growth, busts for one industry, booms for another, sudden wealth collecting in some hands, while elsewhere whole communities collapse, like Flint Michigan, and Viking Greenland, and the many disasters in human history which made survivors abandon homes and villages, and move elsewhere. A lot of families and communities will lose their livelihoods, their homes, their everythings, and face the devastating need to start again. And as that happens, we’ll see different places enact different laws and policies to deal with it, just like after the Black Death. Some places/regimes/policies will increase wealth and freedom, while others will reduce it, and the complicated world will go on being complicated.

That’s why I say we should aim to do better than the Renaissance.

Because we can. We have so much they didn’t. We know so much.

For one thing, we know how pandemics work. We know about germs, viruses, contagion, hand-washing, sanitation, lowering the curve. We can make plans, take action that does something. Forget 1348, even in 1918 we didn’t understand how to treat influenza, how it moved, and hand washing was still controversial. 1918 was a US election year but we didn’t discuss delaying or changing the election, there was nothing we could do to make it safer, we didn’t know about six-feet-apart, or sanitizing voting booths, or have the infrastructure to consider vote-by-mail, all we could do was let men (women still had two more years to wait) vote and die. We’ve come a long way.