A Passion for Porphyry

The Vatican museum: hall after hall of ancient Rome. Shelves crowd the corridors with busts of Caesar, of Cicero, of a hundred obscure Senators, of still more-obscure Romans, anonymous but vivid with two-thousand-year expressions of resolve or grit or whimsy crowded shelf on shelf. Here sits Penelope still patient, Diana hunting, Bacchus laughing merry, while somewhere in the distance the Sistine Chapel lurks, complacent in its celebrity. In the Hall of Animals, Roman hounds sniff at Roman horses, rabbits, crabs, crocodiles, camel heads with their enormous, gummy lips, all stone. The Belvedere Courtyard stunned you with its circle of masterpieces every one of which transformed the history of sculpture: the Belvedere Apollo, the Belvedere Torso that so fascinated Michelangelo, and, as matchless when the Renaissance unearthed it as it was when Pliny called it the best of sculptures 1500 years before, the real Laocoön. The walls and ceilings of the patchwork labyrinth-palace are such an ocean of gilded cornices and marble tracework that it becomes impossible to tell north from south or ground from upper floors, so all sense of grounded space is long gone as you turn the corner into a grand scarlet rotunda, floored with vivid Roman mosaics. Statues of gods and emperors loom, more than twice life-height: grim-faced Athena, tired Claudius, the massive gilded Hercules; while the friend beside you stops dead and, slack-jawed, points at a big stone tub in the middle of the room: “Look at the size of that hunk of porphyry!”

The Vatican museum: hall after hall of ancient Rome. Shelves crowd the corridors with busts of Caesar, of Cicero, of a hundred obscure Senators, of still more-obscure Romans, anonymous but vivid with two-thousand-year expressions of resolve or grit or whimsy crowded shelf on shelf. Here sits Penelope still patient, Diana hunting, Bacchus laughing merry, while somewhere in the distance the Sistine Chapel lurks, complacent in its celebrity. In the Hall of Animals, Roman hounds sniff at Roman horses, rabbits, crabs, crocodiles, camel heads with their enormous, gummy lips, all stone. The Belvedere Courtyard stunned you with its circle of masterpieces every one of which transformed the history of sculpture: the Belvedere Apollo, the Belvedere Torso that so fascinated Michelangelo, and, as matchless when the Renaissance unearthed it as it was when Pliny called it the best of sculptures 1500 years before, the real Laocoön. The walls and ceilings of the patchwork labyrinth-palace are such an ocean of gilded cornices and marble tracework that it becomes impossible to tell north from south or ground from upper floors, so all sense of grounded space is long gone as you turn the corner into a grand scarlet rotunda, floored with vivid Roman mosaics. Statues of gods and emperors loom, more than twice life-height: grim-faced Athena, tired Claudius, the massive gilded Hercules; while the friend beside you stops dead and, slack-jawed, points at a big stone tub in the middle of the room: “Look at the size of that hunk of porphyry!”

Yes, it’s porphyry, a dark, reddish-purple speckly stone, and this room, for the many who enter and ooh and aah and glittering Hercules, is another moment of material illiteracy. Just as a Catholic spots John the Baptist by his hairshirt, and a fashionista a Gucci handbag by whatever alien cues its curves contain, so from the Roman Republic to Napolean a European knew what porphyry implies: Wealth, Technology, Empire, Rome.

Yes, it’s porphyry, a dark, reddish-purple speckly stone, and this room, for the many who enter and ooh and aah and glittering Hercules, is another moment of material illiteracy. Just as a Catholic spots John the Baptist by his hairshirt, and a fashionista a Gucci handbag by whatever alien cues its curves contain, so from the Roman Republic to Napolean a European knew what porphyry implies: Wealth, Technology, Empire, Rome.

Porphyry has become a generic term for igneous rock containing large spots (crystals), but the source of the name is the Greek word for purple, and the purple form is the true original. This is referred to as Red Porphry, Purple Porphyry, or, most aptly, Imperial Porphyry.

The Imperial Porphyry found in Italy came from a single mine in Egypt, the Mons Porphyrites. It was imported by the Romans as a decorative accent stone, for use in tiled floors, as colored columns, or occasionally carved into a vase or sculpture. Its color invokes Royal Purple, but is also very close to the color of the fabulously expensive shellfish-based purple dye which produced the purple stripe which marked the tunics and togas of the Senatorial class. This also dyed the completely purple toga worn by those who occupied the rare and severely powerful office of Censor, a special official created only on occasions, whose task was to examine the state of the Senatorial families and judge which were still worthy of office and who should be removed or added to the roster of Rome’s leading citizens.

The Imperial Porphyry found in Italy came from a single mine in Egypt, the Mons Porphyrites. It was imported by the Romans as a decorative accent stone, for use in tiled floors, as colored columns, or occasionally carved into a vase or sculpture. Its color invokes Royal Purple, but is also very close to the color of the fabulously expensive shellfish-based purple dye which produced the purple stripe which marked the tunics and togas of the Senatorial class. This also dyed the completely purple toga worn by those who occupied the rare and severely powerful office of Censor, a special official created only on occasions, whose task was to examine the state of the Senatorial families and judge which were still worthy of office and who should be removed or added to the roster of Rome’s leading citizens.

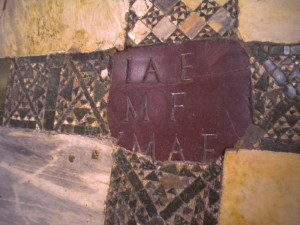

Several Caesars held this special office, so purple, and porphyry, and as their palaces became more opulent it became increasingly an imperial symbol. In Constantinople, once the capitol moved in the late empire, the imperial palace contained an entire room covered in porphyry, and this was traditionally where empresses gave birth, giving imperial princes and princesses the title Porphyrogenos, “born to the purple”.

Porphyry is extremely hard, also dense and heavy. Even lifting a substantial hunk of porphyry is a great feat, let alone transporting it by ship from Egypt. It is also so hard that it takes very strong, well-tempered steel to cut it, and even then, achieving any great degree of precision is very challenging. The Romans had steel good enough, but it too was lost in the Middle Ages, making Roman porphyry artifacts not only symbols of the Caesars but of the impossible godlike skills of the ancients, which their weak successors could only marvel at. It was physical, recognizable proof that the Romans could do the impossible. In addition, the location of the mine in Egypt was lost around the fourth century AD, and not successfully rediscovered until 1823.

Imperial Porphyry has a cousin, green porphyry, or Lapis Lacedaemonius (or Spartan basalt), commonly called Serpentine (confusingly since it IS NOT the same thing as the far softer serpentine subgroup of stones including antigorite, chrysotile and lizardite, but they are all sometimes called serpentine). It is just as hard, coming from a mine near Sparta (or near the modern Greek town of Krokees). It is speckled too though often with larger speckles, many somewhat rectangular or X-shaped. The combination of rich green and purple, usually set in a white Italian marble background, was an extremely popular decorative element seen all over Rome, in the houses of Rome’s imitators, and especially in palaces and churches which re-used floor tiles looted from Roman sites. Porphyry ornaments the floors of Rome’s greatest churches, with the size and density of porphyry among the framing stones increasing toward the altar. The header at the top of this very blog shows a porphyry section from the floor of the Sala della Disputa, the frescoed room in the Vatican which hosts Raphael’s incomparable School of Athens, while the Sistine Chapel Floor (not a phrase you hear often enough) completes the opulence of the other decoration with a dense decoration more purple than white.

Imperial Porphyry has a cousin, green porphyry, or Lapis Lacedaemonius (or Spartan basalt), commonly called Serpentine (confusingly since it IS NOT the same thing as the far softer serpentine subgroup of stones including antigorite, chrysotile and lizardite, but they are all sometimes called serpentine). It is just as hard, coming from a mine near Sparta (or near the modern Greek town of Krokees). It is speckled too though often with larger speckles, many somewhat rectangular or X-shaped. The combination of rich green and purple, usually set in a white Italian marble background, was an extremely popular decorative element seen all over Rome, in the houses of Rome’s imitators, and especially in palaces and churches which re-used floor tiles looted from Roman sites. Porphyry ornaments the floors of Rome’s greatest churches, with the size and density of porphyry among the framing stones increasing toward the altar. The header at the top of this very blog shows a porphyry section from the floor of the Sala della Disputa, the frescoed room in the Vatican which hosts Raphael’s incomparable School of Athens, while the Sistine Chapel Floor (not a phrase you hear often enough) completes the opulence of the other decoration with a dense decoration more purple than white.

In the Middle Ages, then, porphyry meant Rome, specifically the lost power of the Caesars who could reach across oceans and achieve impossible feats. Anywhere porphyry appeared it was a Roman relic, and anyone who had it could claim thereby to be an inheritor, in some small way, of that lost Imperium. Porphyry also came, over the middle ages, to symbolize Christ (reddish purple = blood), but in the Middle Ages everything came to represent Christ, from griffins and unicorns to pelicans and pomegranates (no, it’s totally not a co-opted pagan symbol, why do you ask?), so what distinguished porphyry from the zillion other things that represented Christ was still its imperial connection and its technological unachievability.

Thus everyone who’s everyone wanted porphyry, and if you wanted it, you had to steal it. The only porphyry in Europe lay in things the Romans built, so every prince and republic and sculptor who wanted this symbol of Roman power had to steal it from the source. Want to put in a nice porphyry floor for a Church? Loot it from a Roman temple. Want to advertise the imperial majesty of Mary Queen of Heaven? Make the altar out of an old, repurposed porphyry sarcophagus. If a pope wanted porphyry columns for his tomb, he had no better source than to go to some surviving Roman temple (say, the Pantheon…) and rip out the porphyry, perhaps if he’s polite substituting some less valuable stone to keep the looted edifice from falling down.

Some places already had porphyry brought there by the Romans, and in these cases it was proudly displayed as proof of the noble Roman origins of a town or province. Even in Florence, on the baptistery which is the literal heart and center of the city, the gilded Gates of Paradise are still flanked by two old, cracked and mended, asymmetrical dark reddish columns, built into green and white facade despite a complete chromatic mismatch. So old and dull are they that many don’t even notice them upon first or even third visit, but these are porphyry, relics of the Roman-era Church of Santa Reparata, or its predecessor, preserved and re-used here as proud proof of Florence’s Roman roots.

Porphyry sculpture was even more impressive than a tile or column, since working such an adamantine substance into complex shapes required immense time and skill. Diamond was rare and valuable and not a practical tool for trying to make a large chisel to work large stone, but short of diamond the only means to shape porphyry was to rub it against another piece of porphyry for a very long time, grinding both down, a clumsy, labor-intensive and imprecise technique. Many, especially the Medici family, poured funds and efforts into researching ways to make a metal sharp enough to carve porphyry, or a solvent capable of weakening it, in hopes of adding this to their list of resurrected Roman achievements. Even before they succeeded, however, possessing a Roman porphyry sculpture was an even grander boast than possessing simple tiles, and at last now we can understand why, in the Uffizi Gallery, where the great Roman sculpture treasures of the Medici are still housed, one comes around the corner to the very center of the U-shaped gallery, expecting to see in the center some exceptional masterpiece, an Emperor or bold Athena, one sees instead the mangled, limbless torso of an animal. Look again: those hips, those hanging teats. This is the mangled, limbless torso of a porphyry she-wolf, the symbol of Rome herself.

Naturally, the greatest concentration of porphyry lay (and lies) in and around Rome itself. The farther you are from Rome, the scarcer (and more impressive) porphyry becomes. Florence had a couple columns and the odd basin, but for more porphyry they had to buy or steal from Rome, or elsewhere. The Venetians carried off large pieces of porphyry from Constantinople when they looted it, and still display them proudly as pulpits on either side of the main alter in San Marco. Porphyry in northern Italy is comparatively scarce, so a Venetian palace with a few roundels in its facade makes a real statement. Even as far as France, when Louis was decorating Versailles, porphyry was scarce indeed, but what few busts and vases he got hold of went straight into the best places: the throne room, and the Hall of Mirrors where every visitor would see, and understand, Louis = Caesar.

The pope always wins the Who-Has-The-Most-Porphyry Competition, and the Vatican is its grand display case. The staggeringly enormous porphyry basin in the round sculpture room in the Vatican palace is referred to as Nero’s bathtub, and is the largest piece of porphyry I have ever seen; I would not be surprised to discover it is the largest in the world.

One is generally still reeling from trying to imagine the staggering cost and difficulty of creating and moving such an object, when in the next room one encounters an even more impossible vision: two enormous solid porphyry sarcophagi, both taller than a standing person, and covered in deep relief carvings of horsemen, prisoners and acanthus leaves. This is Rome indeed. Specifically, these are the sarcophagi of the women of Constantine’s family, including the tomb of his mother, Helen, or more specifically Saint Helen, who traveled to the holy land and brought back the True Cross and the Lance of Longinus and… at least one other major relic, but I can’t right now remember whether it was a nail or part of the Crown of Thorns, or perhaps that piece of the Holy Sponge they have in Rome… (Spot the Saint moment: Helen’s attribute in art is that she carries the cross.) Regardless, the two tombs have no Christian imagery, just the most Roman of Roman decorations, horsemen leading vanquished prisoners for Helen, and for the other fertility images. In deep, impossible relief. In an era when it was a substantial feat to scrape two looted pieces of porphyry into sufficiently matching shapes to make them seem symmetrical in a floor pattern, there is no purer proof of the godlike power of the ancients. After that, there is just too much, and every further encounter with porphyry in the Vatican labyrinth feels like one, two, three, five, ten too many.

St. Peter’s is just as much a showroom for porphyry, with columns, tiles, tombs. Every purple object that, from a distance, makes you think “is that porphyry?” turns out to be the genuine article. And it’s worth keeping in mind that, except for the most modern pieces, they’re all relocated chunks of what were Roman temples scattered around the city from the Caesars’ days.

One large porphyry round in the floor close to the entrance is supposed to be the stone from the original St. Peter’s on which Charlemagne was crowned the first Holy Roman Emperor (and successor to the Caesars) on Christmas day, 800 AD. It’s just inside the entrance in the exact center of the Church, sort of balancing the altar, secular power facing sacred.

Perhaps my favorite piece of papal porphyry, though, is this set of porphyry keys carved and set into other stonework in the threshold of the Church, so every visitor who enters walks across them. Most ignore them, but in the pre-modern world one glance at heraldic papal keys in porphyry spells a very special kind of awe: not only does the pope have Porphyry but apparently he has the power to carve it into a Christian shape. Clearly he is Rome’s successor. With so many visiting feet for so many centuries, the papal threshold keys are also the best proof I know of the extreme hardness of porphyry, since the stone around them is worn down by more than a centimeter, while the keys stick up, unharmed by the tread of millions. The Florentine Museum of the History of Science has examples of scientific instruments and grinding stones fashioned from porphyry, chosen for its rigidity and inelasticity as well as for its opulence.

Perhaps my favorite piece of papal porphyry, though, is this set of porphyry keys carved and set into other stonework in the threshold of the Church, so every visitor who enters walks across them. Most ignore them, but in the pre-modern world one glance at heraldic papal keys in porphyry spells a very special kind of awe: not only does the pope have Porphyry but apparently he has the power to carve it into a Christian shape. Clearly he is Rome’s successor. With so many visiting feet for so many centuries, the papal threshold keys are also the best proof I know of the extreme hardness of porphyry, since the stone around them is worn down by more than a centimeter, while the keys stick up, unharmed by the tread of millions. The Florentine Museum of the History of Science has examples of scientific instruments and grinding stones fashioned from porphyry, chosen for its rigidity and inelasticity as well as for its opulence.

The ability to carve porphyry was eventually recovered, and in the 18th century Roman relics were transformed into large numbers of sculptures, especially busts, of rather questionable taste and quality. Porphyry remains hard to work with, so the very subtle curves and scratches necessary to make a really lifelike human portrait are simply impossible in it. Its products are always a little too smooth and shiny, the edges of the eyes clumsily cut, the wrinkles a little too smooth, like waves rather than folds. Also, purple with speckles is not the most flattering skin tone.

Fake porphyry was, naturally, an industry as well, and many of the most famous buildings in Europe contain not only real porphyry but painted fake porphyry, made of plaster or wood painted with the signature purple and speckles. This was most often done for bases on which statues sat, or for trim around rooms, but the Villa Borghese in Rome contains whole tabletops of fake porphyry, with real porphyry busts nearby to make them plausible. Porphyry was also a popular ingredient in painted scenes, especially paintings of imagined palaces, and of places intended to be ancient Rome. And heaven, of course. The halls of Heaven, where saints and angels pose for altarpieces, have plenty of porphyry.