Spot the Saint: Franciscans (Friars Minor)

A dear friend’s visit and a weekend in Rome has delayed this update, but while I was trying to write up my recent tour of fascinating Roman churches, a mix of famous and obscure, I discovered that I couldn’t make the discussion make sense unless I covered a couple other related topics first. I shall begin with the Order of the Friars Minor, aka. the Franciscans (just as the Dominicans are officially the Order of Preachers).

In art, Franciscans wear plain habits that are usually a gray-brown color, but sometimes gray and sometimes brown. There are several sub-groups of Franciscans, including the Capuchins, but for our Renaissance purposes, and in art, we are concerned only with the main branch. The Friars Minor are so called in memory of the focus on modesty, humbleness and obedience of their founder. They were founded at the very beginning of the 1200s, just like the Dominicans. This means that during the lives of early Renaissance figures like Dante and Petrarch, the Franciscans were a powerful but recent movement, something Italy could be proud of.

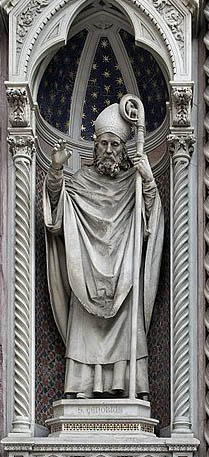

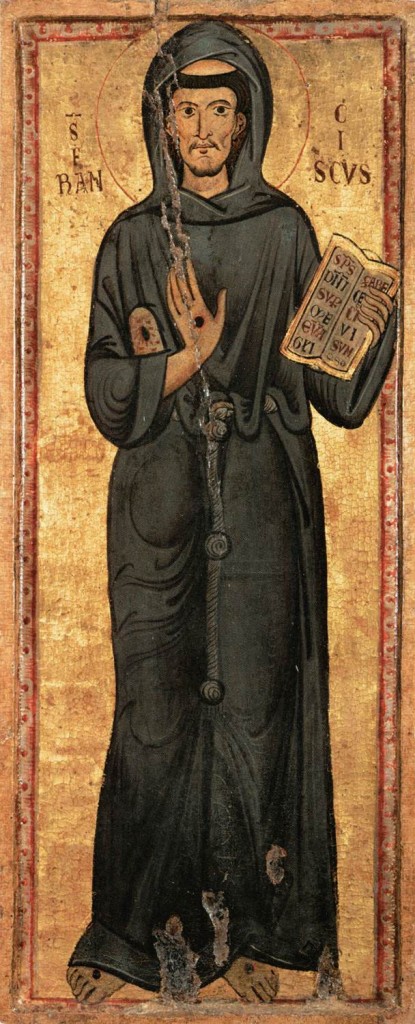

Saint Francis (San Francesco) 1181/2-1226

- Common attributes: Franciscan habit, stigmata (wounds of Christ on his hands, feet, side)

- Occasional attributes: lamb, bird, wolf, T-shaped cross (“Tau”)

- Patron saint of: The Franciscan order, animals, merchants

- Patron of places: Italy (yes, all of it), Assisi

- Feast day: October 4th

- Most often depicted: Receiving stigmata from an angel, nude as a young man being received into the Church, kneeling before the pope, preaching to animals, in front of a sultan intending to walk through fire, embracing Saint Dominic, dead with people examining his corpse

- Relics: Assisi, Basilica di San Francesco

Francis is Patron Saint of Italy. Not part of it, not a town, not a province, not an order, not a profession; Italy. Italy had a lot of major saints to choose from: Peter, Paul, Mark, John the Baptist, John the Evangelist, Jerome, Ambrose, Gregory… the fact that the all-important home province went to a saint from the late twelfth century is proof by itself that Francis is something very special within Heaven’s high heirarchy.

Francis’ father was a merchant and his mother was French. As a youth he spoke French, loved French clothes, French songs, French everything, and his baptismal name of Giovanni was soon forgotten in favor of the nickname “Francesco” i.e. little Frenchman. He took part in some military stuff when young, during which time he seems to have had a religious crisis, and thereafter showed a growing interest in monastic life. One day, on the way home from selling some of his father’s goods at market, he couldn’t take it anymore, went into a church and insisted he was going to stay there and become a monk. The priests were terrified, knowing of his father’s wealth and inevitable wrath, and tried to force the boy to leave, but he refused. He tried to give them the money he had been carrying home, but they didn’t dare touch it, and the bag of coin sat in the church, abandoned out of fear. After a while Francis’ father came hunting for him, enraged, and insisted that he return. Francis gave the money back, but refused to come himself. His father continued to insist that Francis was his and was coming home with him. Francis then stripped naked and handed his clothes to his father, saying he had returned everything that was his father’s and the rest belonged to god. At this point, the bishop intervened, and wrapped his cloak around the young man, welcoming him into the Church. Francis then went on to be the most enthusiastic and influential monk of all time.

Why was Francis so incomparably important? Put simply, he changed what the word “religious” meant. In the Middle Ages, when one said a “religious person” one meant a monk, nun or priest, or maybe a hermit. That’s simply what the word meant. There was not really the concept that a lay person, particularly an urban person like a merchant or crafts worker, could have a meaningful religious life. One wanted them to be baptized and to try to live virtuously, but that was mostly in order to prevent earthly divine smiting, and expectation was that someone living a secular life was likely not heaven-bound most of the time, and certainly didn’t participate in religious life or thought any more than occasional churchgoing. Francis changed that. He came into the cities and preached to the urban poor. He encouraged everyone to think about religious questions and have a personal intellectual religious life. He suggested that merchants and workmen might gather once a week for religious meetings, wear monastic symbols under their clothes as self-reminders of their faith, and in other ways meaningfully do things “religious” people did despite, or rather as an enhancement to, their worldly lives. He made Christianity welcoming and accessible to ordinary people in a way it really hadn’t been before. He made people welcome, and for that people adored him, and still do.

Why was Francis so incomparably important? Put simply, he changed what the word “religious” meant. In the Middle Ages, when one said a “religious person” one meant a monk, nun or priest, or maybe a hermit. That’s simply what the word meant. There was not really the concept that a lay person, particularly an urban person like a merchant or crafts worker, could have a meaningful religious life. One wanted them to be baptized and to try to live virtuously, but that was mostly in order to prevent earthly divine smiting, and expectation was that someone living a secular life was likely not heaven-bound most of the time, and certainly didn’t participate in religious life or thought any more than occasional churchgoing. Francis changed that. He came into the cities and preached to the urban poor. He encouraged everyone to think about religious questions and have a personal intellectual religious life. He suggested that merchants and workmen might gather once a week for religious meetings, wear monastic symbols under their clothes as self-reminders of their faith, and in other ways meaningfully do things “religious” people did despite, or rather as an enhancement to, their worldly lives. He made Christianity welcoming and accessible to ordinary people in a way it really hadn’t been before. He made people welcome, and for that people adored him, and still do.

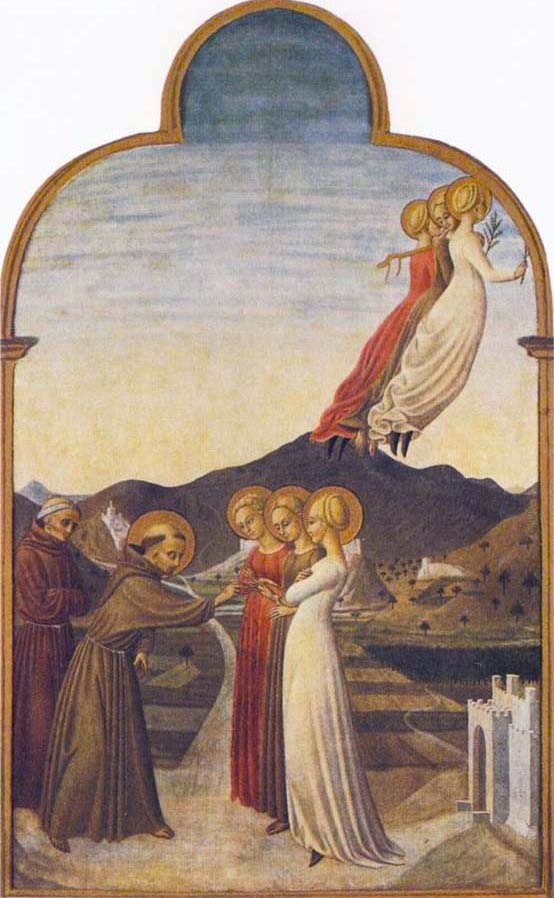

Francis was also very hard core about the monastic life. Francis was so fierce in his renunciation of wealth and his fixation on wandering and begging that, even when he was an invited guest at someone’s house, he would nonetheless insist on going outside to beg for his supper on the street. Francis was spiritually married to the Angel of Poverty, one of the three angels of monastic vows, who hangs out with the Angel of Chastity and the Angel of Obedience.

In honor of Francis’ dedication on this front, to this day the Franciscan order, is the only mendicant (begging) order whose members are still forbidden to own any property whatsoever. All items possessed by Franciscans, from the grand Basilica of St. Francis to the sheets on their dormitory beds legally belong to the pope who lends them to the Franciscans, and the pope can walk up to any Franciscan and demand the shoes off his feet and he has to give them up (I am assured that popes don’t generally actually do this, but I imagine many popes have had fun thinking about it). The Friars Minor also focus on humility, following the model of Francis who, despite being a great and popular leader, never let himself be in authority, always deferring to the commands of others, and preferring to be led, not followed.

Francis was also big on the mortification of the flesh. He referred to his physical body as “Brother Ass” which had to be frequently beaten into obedience; he practiced intense fasting, as well as physical mortification, and, among other things, would often throw himself naked into snow (whenever Italy’s clement environment made snow an option). So fierce was he in this self-mortification that he often made himself quite sick, and would likely have died sooner than he did had his fellow monks not frequently ordered him to eat more, take it easy on himself, permit himself richer foods, etc., and orders Francis eagerly obeyed (thank you Angel of Obedience).

Francis himself did preach, to anybody and anything who would listen (people, birds, wolves, insects), but he led mainly by example. He himself was not particularly literate and did not know Latin pretty much at all, nor sophisticated theology, and the only book he left was a little collection of sweet prayer poem-songs.

Francis himself did preach, to anybody and anything who would listen (people, birds, wolves, insects), but he led mainly by example. He himself was not particularly literate and did not know Latin pretty much at all, nor sophisticated theology, and the only book he left was a little collection of sweet prayer poem-songs.

Now, when a new, weird, popular and powerful movement enters a religion and starts getting a lot of momentum, attention, press and money, and is led by someone who isn’t quite preaching the usual, the religious leaders inevitably become nervous. In the Catholic tradition, a moment of examination arrives, when the new movement hovers on the edge between being welcomed as a breath of fresh reform, and being expunged as a heresy. It could easily have gone either way with Francis, whose changes to the usual way Chrisitanity had been practiced, particularly in urban settings, was so extreme. But, especially since Francis was so keen on obedience, he was eager to be part of the Church rather than against it, and was happy to formally acknowledge the authority of the pope.

When one sees paintings of scenes from the life of Francis, one of the most common and, on the surface, least interesting is a scene showing him kneeling before the pope, being received in Rome. This may seem boring, the sort of moment which should go without saying, but the scene, and repeated images of the scene, were a critical reminder to all that, powerful as the Franciscan movement was, the Franciscans served Rome, Francis served the pope, and the old structure still stood.

The rivalry with the Dominicans came about mainly after Francis’ death. It was partly a power and money thing. Even though both orders were founded on the notions of poverty and modesty, there is a life cycle of monastic movements, which generally runs:

- Charismatic leader wants to live more modesty, without corruption, imitating Christ, so breaks off from the corrupted institutions of the Church.

- Many others find spiritual richness in this, and follow him/her.

- Movement takes off, gets official recognition from the Church, becomes established.

- People who like the movement donate wealth and land to it, both out of respect for the order, and in hopes that the monks/nuns will pray for them (and thus get them out of purgatory).

- Movement becomes wealthy and powerful, and noble families start sending their younger sons into it in order to gain wealth and power.

- Corruption leads a charismatic leader to want to break off and live more modestly, imitating Christ.

- A new order is formed… (Lather, rinse, repeat.)

This eventually happened even to the Franciscans, spawning the more extreme Capuchin sub-group, and it was mainly in the money and power seekers that the orders rivalry grew. But there was also an intellectual contrast, as I mentioned. The well-educated scholar-priest Dominic believed that the best way to reach God was through knowledge, since God is Truth. Studying the nature of God, the soul, Christ, heaven, even the Earth would help the soul understand the divine and, through understanding, reach toward union with it (those of you who smell Plato’s residue in this are spot on). The less educated and more passionate Francis focused in stead on reaching God through fierce desire, since God is Love, and that a heart that deeply and sincerely loved God would be drawn toward His heavenly light (those of you who also smell Plato here are also right). Both movements, and both techniques, were much loved, but Francis’ focus on simplicity, and the idea that one could reach God through passion by itself, without the rigor and expense of education, made the Franciscan movement able to appeal much more broadly to the poor populace, in contrast with the inherent elitism of Dominican literate culture. To Dominic went the universities, to Francis went the crowds.

This eventually happened even to the Franciscans, spawning the more extreme Capuchin sub-group, and it was mainly in the money and power seekers that the orders rivalry grew. But there was also an intellectual contrast, as I mentioned. The well-educated scholar-priest Dominic believed that the best way to reach God was through knowledge, since God is Truth. Studying the nature of God, the soul, Christ, heaven, even the Earth would help the soul understand the divine and, through understanding, reach toward union with it (those of you who smell Plato’s residue in this are spot on). The less educated and more passionate Francis focused in stead on reaching God through fierce desire, since God is Love, and that a heart that deeply and sincerely loved God would be drawn toward His heavenly light (those of you who also smell Plato here are also right). Both movements, and both techniques, were much loved, but Francis’ focus on simplicity, and the idea that one could reach God through passion by itself, without the rigor and expense of education, made the Franciscan movement able to appeal much more broadly to the poor populace, in contrast with the inherent elitism of Dominican literate culture. To Dominic went the universities, to Francis went the crowds.

Still, it was an amicable rivalry, since both groups had the same goals. Perhaps my favorite token of this is in Dante’s Paradiso, where the great and ultra-educated Dominican theologian Thomas Aquinas, before administering the theology exam which Dante must pass to get to the upper levels of Heaven, recites a long, praise-filled biography of Francis, founder of his order’s rival, but still loved by all in Heaven.

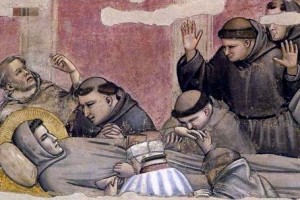

Francis was the first saint to have stigmata, the wounds of Christ on his hands and feet, and the spear wound in his side. An eyewitness account states that he was in the mountains one day when an angel (or possibly a flying crucifix) zapped him with rays of light, and gave him the wounds. We have accounts of the examination of his body upon his death (often depicted in art, since many were curious to examine the famous wounds up close); medical scientists reading the descriptions of the wounds as having been strange and hard and bumpy believe them to have been some kind of cancer. In art, Francis is usually holding his hands and feet out so you can easily see the nail marks on them, and often his robe has a slit so you can see the spear wound. Sometimes rays of golden light are radiating from the wounds. The stigmata and his Franciscan habit are usually more than enough to make him recognizable. While he is often depicted in more recent art with a lamb or bird or animals, since the story of him preaching to animals is popular, in Renaissance art he didn’t need that; stigmata was enough.

Francis’ story also has enough interesting episodes that he has many distinctive common activities you can keep an eye out for:

Francis’ story also has enough interesting episodes that he has many distinctive common activities you can keep an eye out for:

- As a young man, being wrapped in the bishop’s cloak as he stands naked before his father

- Receiving the stigmata

- Marrying the Angel of Poverty

- Hugging Saint Dominic

- Appearing in a dream, where the pope sees Francis holding up a crumbling church (prophesying how important Francis would be)

- Kneeling before and being received by the pope

- Dead, his corpse being inspected by curious mourners, one of whom is reaching into the wound on his side

“Walking through fire before the sultan.” I put this in quotes because the standard image shows him standing before the Sultan, with a big bonfire, and Francis in front of it, while some Arab-looking people shudder and gawk. The story is that Francis went to the holy land to try to convert the Sultan (or get martyred; it’s win-win!). He preached earnestly in front of the Sultan, who said he was a sweet kid, and gave him some presents and told him to go home. Francis then insisted he was going to walk through fire to prove his faith, and asked if the Sultan’s Muslim spiritual leaders would do the same. Nobody but Francis thought this was a good idea, and, in the official story, the Sultan told Francis that he had convinced him, and that the Sultan had secretly personally converted, but that he couldn’t reveal that publicly without causing a civil war, so he told Francis to please go home and stay safe before someone murdered him. Francis then went home, so the scene is actually a depiction of Francis not walking through fire in front of the sultan.

“Walking through fire before the sultan.” I put this in quotes because the standard image shows him standing before the Sultan, with a big bonfire, and Francis in front of it, while some Arab-looking people shudder and gawk. The story is that Francis went to the holy land to try to convert the Sultan (or get martyred; it’s win-win!). He preached earnestly in front of the Sultan, who said he was a sweet kid, and gave him some presents and told him to go home. Francis then insisted he was going to walk through fire to prove his faith, and asked if the Sultan’s Muslim spiritual leaders would do the same. Nobody but Francis thought this was a good idea, and, in the official story, the Sultan told Francis that he had convinced him, and that the Sultan had secretly personally converted, but that he couldn’t reveal that publicly without causing a civil war, so he told Francis to please go home and stay safe before someone murdered him. Francis then went home, so the scene is actually a depiction of Francis not walking through fire in front of the sultan.

Saint Antony of Padua (San Antonio) 1195-1231

Saint Antony of Padua (San Antonio) 1195-1231

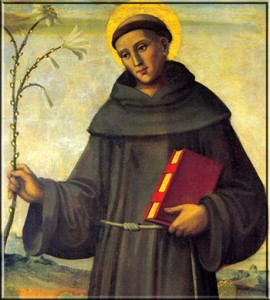

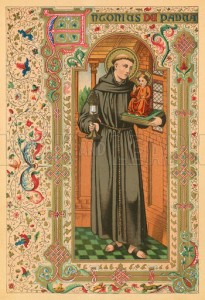

- Common attributes: Franciscan habit, tonsure

- Occasional attributes: Book, flaming heart, carrying Christ child, lily, occasionally bread or fish

- Patron saint of: Lost objects (and those seeking them), travelers (and their hosts), the elderly, lots of other rather random typical stuff like barrenness, harvests, oppressed people etc.

- Patron of places: Portugal, Brazil, Native Americans

- Feast day: June 13th

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other Franciscan saints, preaching, holding the Christ Child and looking friendly

- Relics: Padua, Basilica di San Antonio

Antony, or Anthony, was originally named Fernando, and came from Lisbon, Portugal, from a noble family, but insisted on becoming a friar. An Augustinian friar, at first, an old and lucrative order, which Thomas Aquinas’ parents would’ve approved of. When he was still young, early on in the history of the order (11 years after Francis founded it) five Franciscans came through Lisbon on their way to Morocco, and stayed in the guest house young Antony ran. He was impressed by them, and even more impressed when they got martyred (a great political coup for the Franciscans, and good proof of why the Dominicans made such a fuss over Peter “I have a big knife sticking out of my head” Martyr). Seeing the five martyrs’ bodies as they were being brought home, young Antony was struck by their devotion and got special permission to quit being an Augustinian in order to become a Franciscan.

Since there weren’t Franciscans outside Tuscany yet really, Antony went to Tuscany and lived as a semi-hermit with the order, doing nothing in particular, until one day a bunch of Dominicans came over to, you know, do monk things together, and there was a bit of a fuss over whose job it was to preach to the assembly, each order expecting the other to step forward. After some kerfluffle, somehow Antony wound up on the podium, and everyone discovered suddenly that he was an extremely well educated child of the nobility and preached with extreme clarity and erudition. A stellar career of preaching, fame and distinguished service followed. He did not succeed in his childhood dream of martyrdom, but did become one of the best loved and most famous of his order and a major international hero of the church.

Since there weren’t Franciscans outside Tuscany yet really, Antony went to Tuscany and lived as a semi-hermit with the order, doing nothing in particular, until one day a bunch of Dominicans came over to, you know, do monk things together, and there was a bit of a fuss over whose job it was to preach to the assembly, each order expecting the other to step forward. After some kerfluffle, somehow Antony wound up on the podium, and everyone discovered suddenly that he was an extremely well educated child of the nobility and preached with extreme clarity and erudition. A stellar career of preaching, fame and distinguished service followed. He did not succeed in his childhood dream of martyrdom, but did become one of the best loved and most famous of his order and a major international hero of the church.

In art, Antony is very tricky. His attriutes have varied a lot over time, tending gradually toward the more adorable. Early on he usually has a lily and a book, just like Dominic except with a brown/gray Franciscan habit. Later he often has a flaming heart, representing his passion for preaching. Sometimes he has flame and separately a heart, just kind-of sitting there, on a tray or something. He also, in early art, often had a book with an image of the Christ Child on it, then later a book with the Christ Child kind-of coming out of it as if it were coming to life, and, eventually, he just holds the Christ Child (do not confuse him with the equally adorable St. Christopher who does the same, and who is, with Antony, co-patron saint of travelers).

These days Antony almost always has the adorable Christ Child with him and the whole thing is terribly cute. Often in early art, though, the best way to spot him is process of elimination: there are two Franciscans here and only one can be Francis, therefore the one without stigmata is probably Antony. Antony is also the only major Franciscan to carry a book, since Francis was not particularly literate, and left only a few vernacular songs.

As patron saint of lost objects and those seeking them, Saint Antony is a very popular and frequently-invoked patron in practical and everyday life.

One of my favorite proofs of how incomparably valuable relics were in the Renaissance is the official Life of St. Antony of Padua. The little book is divided into three sections of roughly equal length. The first describes his life. The third describes his posthumous miracles. The middle one describes the virtual civil war which broke out in Padua after his death, when it was obvious he would be made a saint, so the different groups who had a potential claim to his body (the monastery he lived at, the one he was visiting when he died, local lords, local communal government) divided into fiercely-opposed camps even before he died, and in the end martial law had to be declared and the force of the Holy Roman Emperor called in to settle the dispute.

Saint Bernardino of Siena, 1380-1444

Saint Bernardino of Siena, 1380-1444

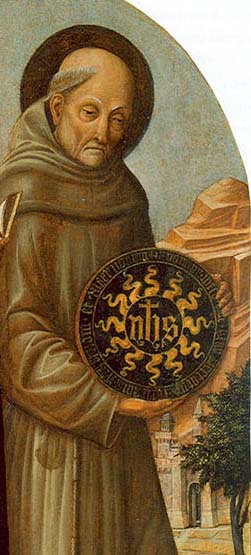

- Common attributes: Franciscan habit, plaque or other item with the Coat of Arms of Christ! (Christogram), narrow chin and dour expression

- Occasional attributes: Three mitres (representing 3x he refused to be made a bishop; note, despite looking I have NEVER actually found him with this attribute).

- Patron saint of: Advertising, advertisers, public relations work & PR employees, chest conditions (coughs, asthma etc.), gambling addicts

- Patron of places: Aquila (Italy), San Bernardino CA

- Feast day: May 20th

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other Franciscans, glaring at you looking angry, brandishing the Coat of Arms of Christ! (Christogram) and making you feel guilty you don’t have one. Yes, you! I’m talking to you!!

- Relics: Aquila, Italy; his personal tablet with the Coat of Arms of Christ! is at Santa Maria in Aracoeli in Rome.

Bernardino was an orphan from a noble family, and became an extremely popular preacher. He resolved feuds, reconciled enemies, fired hearts, drew crowds, held vast bonfires of the vanities, and, when he was eventually called to Rome by the inquisition, who needed to make sure everything he did was orthodox, he impressed the pope so much that the pope had him preach in Rome and held a big procession. He turned down offers of being made bishop of Siena, Ferrara and Urbino in turn, to focus on his preaching rather than career things. He also ministered to the sick, and contracted the Black Death himself, from which he recovered.

Bernardino’s big thing was the Christogram, aka. the Coat of Arms of Christ! A Christogram is when you use an abbreviation of some part of one of Jesus’ names, i.e. X for Christ, or IHS for the Greek form of Jesus. Bernardino used a certain common version of the IHS monogram, surrounded by a distinctive circle with radiating sun rays, which had been a favorite of, among other figures, St. Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernardino would end every sermon by dramatically unveiling a tablet with the Coat of Arms of Christ on it, gilded, to the great excitement of the crowd. Bernardino encouraged people to put it everywhere, and even suggested that in a perfectly pious world all coats of arms would be replaced with the Coat of Arms of Christ! Thanks to him you see the Coat of Arms of Christ! on Churches and even simple houses all over Tuscany and central Italy, and in a rather Kilroy-esque sense, it always translates in my mind to “Saint Bernardino of Siena was here.”

Bernardino’s big thing was the Christogram, aka. the Coat of Arms of Christ! A Christogram is when you use an abbreviation of some part of one of Jesus’ names, i.e. X for Christ, or IHS for the Greek form of Jesus. Bernardino used a certain common version of the IHS monogram, surrounded by a distinctive circle with radiating sun rays, which had been a favorite of, among other figures, St. Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernardino would end every sermon by dramatically unveiling a tablet with the Coat of Arms of Christ on it, gilded, to the great excitement of the crowd. Bernardino encouraged people to put it everywhere, and even suggested that in a perfectly pious world all coats of arms would be replaced with the Coat of Arms of Christ! Thanks to him you see the Coat of Arms of Christ! on Churches and even simple houses all over Tuscany and central Italy, and in a rather Kilroy-esque sense, it always translates in my mind to “Saint Bernardino of Siena was here.”

In art, Bernardino wears a Franciscan robe, and usually carries the Coat of Arms of Christ! He also generally looks like he’d be no fun at a party.

In art, Bernardino wears a Franciscan robe, and usually carries the Coat of Arms of Christ! He also generally looks like he’d be no fun at a party.

Bernardino is one of the few saints who lived late enough that Renaissance art was developed enough that there were good, lifelike portraits of him made while he was still alive. As a result, actual images of his real face were available when the first icons were made, so he doesn’t have a generic face in art but a distinctive one, based on what he seems to have really looked like. He looks… like he’d be no fun at a party. That’s my best description: a narrow, dry, bony face with a very pointed chin and sunken cheeks, who just looks like he’s about to go on and on about, well, in his case probably the the Coat of Arms of Christ!

The unique face does make him extra fun to spot, though, since it feels more like recognizing a real person than a symbol of a person, and sometimes it’s enough by itself to spot a dour, prune-faced Franciscan to know it’s him, even if some artist didn’t include his Coat of Arms of Christ!

Here, by the way, here is the actual Saint Bernardino of Sienna, visible in his tomb in Aquila, Italy, which proves that his particular Franciscan habit was more on the brown side than gray:

The variable attributes on Antony make Franciscans a little hard to tell apart, but usually a simple mental order of operations flow chart will do the trick:

- (1) Does he have stigmata? If yes, it’s Francis. If not…

- (2) Does he have the Coat of Arms of Christ!? If yes, it’s Bernardino. If not…

- (3) Does he have a lily, a book, a heart, fire, or a baby? If yes, it may well be Antony.

- (4) Does he lack all of the above, and look like a narrow-chinned un-fun guy? If so, back to Bernardino as our prime suspect.

- (5) If none of the above, you may be dealing with a different Franciscan.

And now, Spot the Saint Quiz Time:

Skip to the next Spot the Saint entry.

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)

Saint Reparata (Santa Reparata)