Spot the Saint: Sebastian and Catherine of Alexandria

The newest installment of our attempt to become literate in the medieval sense of being able to “read” what’s going on in religious art.

The newest installment of our attempt to become literate in the medieval sense of being able to “read” what’s going on in religious art.

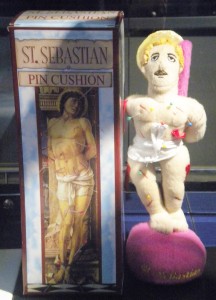

Saint Sebastian (San Sebastiano)

- Common attributes: Naked except for a loincloth, young, handsome, arrows sticking out of him, wrists bound

- Occasional attributes: Well, his hands aren’t free so he can’t hold a martyr’s palm frond, or anything else really

- Patron saint of: Soldiers, protection against arrows, protection against plague, athletics/athletes, a few other things

- Patron of places: Milan, Rome, many other scattered towns

- Feast days: January 20 (Dec. 18)

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, tied to a tree, tied to a column

- Close relationships: Converted a few other early Romans who became obscure saints

- Relics: Rome, Basilica Apostolorum, aka. San Sebastiano fuori le mura,

Saint Sebastian was a third-century Roman saint, martyred by Diocletian. He is supposed to have been a captain of the Praetorian guard, but consoled and encouraged Christian prisoners and converted many, including through the miracle of curing a mute woman. St. Ambrose says Sebastian was from Milan, so his cult there is substantial (as is the cult of Ambrose who was bishop of Milan). According to the hagiographies (hangman word of the day), which were all written at least 100 years after his death, Sebastian was shot with arrows at Diocletian’s orders, but miraculously survived and was rescued and healed by the early Roman saint Irene (wife of Saint Castulus, the secretly Christian Chamberlain of Emperor Diocletian). After recovering from the arrows, Sebastian yelled at Diocletian in the street about theology, and was thereafter clubbed to death, and his corpse thrown in a privy, whence it was rescued and buried by the same Irene, who was also martyred later, as was Castulus. Between the arrows and clubbing, Sebastian is sometimes awarded the distinction of people saying he was martyred twice.

Sebastian was sometimes one of the “Fourteen holy helpers“, an official list of anti-plague saints, including the virgin martyrs Margaret, Barbara and Catherine (of Alexandria), plus an inconsistent list of others often including Christopher and Elmo.

In art, Saint Sebastian is what you do in the Renaissance when you want to have a picture of a sexy naked man without getting in trouble. This is also half of why the arrows rather than the clubbing are the favorite subject. The other half is that the resistance against arrows is a big source of his role as a protector against the plague, especially the bubonic plague, which, as you can imagine, made him extremely popular from 1348 on. The fact that a saint associated with archery is also the warden against the plague is, of course, no relation to the association between plague and arrows in Norse culture (see uses of the Hagalaz and Nauthiz runes), and has even less to do with the extremely handsome and usually nearly-naked Apollo, god of plague and archery.

Sebastian’s relics are in Rome at San Sebastiano fuori le mura, but he isn’t one of these saints anyone has a monopoly on (like Mark and Peter), so reliquaries with small bits of him are common, and there’s one in San Lorenzo.

Saint Catherine of Alexandria (San Caterina)

Saint Catherine of Alexandria (San Caterina)

- Common attributes: Crown, large spiked wooden wheel

- Occasional attributes: Robes, bridal veil, sword, palm frond (common to all martyrs), lilies (common to all virgins)

- Patron saint of: Maidens, unmarried girls, spinsters, spinners & wheelwrights and all craftsmen who work with wheels, theologians, librarians, nurses, knife-sharpeners, lots of things

- Patron of places: University of Paris, Alexandria, Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai

- Feast days: November 25 (24 in Russia)

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, breaking the wheel her captors were trying to use to break her, being beheaded, being rescued by angels

- Close relationships: Often depicted with other major virgin martyr saints, Barbara & Margaret

- Relics: Mount Sinai

For those who keep historical collections of women who were awesome, Catherine of Alexandria definitely belongs on the list (if she existed, which is in some doubt, but what the hey, people thought she did and sometimes that’s enough.) She was the daughter of the Roman governor of Alexandria right around 300 AD. She was thus from one of the best and wealthiest families in one of the most important and wealthy cities in the empire, and received an exceptional education in full Greco-Roman philosophy style. As a young woman she declared to her parents that she would only marry someone who was richer, nobler, smarter and more beautiful than she was, a hard requirement which was eventually satisfied by… wait for it… Christ! She converted in her teens somewhere, and refused to marry, dying a virgin saint. She is then supposed to have used her considerable influence and education to try to convince Emperor Maximian to stop persecuting the Christians. Being unwilling to flat-out kill the daughter of a noble governor, the emperor gathered pagan philosophers from around the empire and sent them to debate with her. She out-debated them all, and, in fact, converted them all, and converted the Empress too. Maximian then ordered her to be broken on the wheel (not a very Roman choice, but whatever). The wheel broke when she touched it, so instead she was beheaded.

Catherine’s medieval cult was very popular, and she especially patronized women and pilgrims, as well as disease victims. She’s one of few saints whose hagiography claims that she, in her dying moments, specifically prayed to God to grant the prayers of those who honored her, so she serves as one of the stories justifying the whole saint cult. Catherine’s body was discovered in 800 AD, with its hair still growing and a miraculous healing oil dripping from it, which is still gathered annually on her feast day. In the 1960s, when the Vatican was feeling historical, they removed her saint’s day from the calendar due to lack of evidence that she really existed, but they put it back in 2002 due to everyone insisting that she is awesome. Even the Anglicans and Lutherans still honor Catherine as a major role model.

In Florentine art at least, after the Virgin Mary, Catherine of Alexandria is one of the female saints one sees most often. Her spiked wheel makes her easy to spot, and she also usually has a crown, which is either an allegorical representation of her sanctification or a symptom of Medieval people not really wrapping their minds around the difference between a roman governor and a king, thus between a governor’s daughter and a princess. In art, altarpieces especially, painters usually like to have saints in pairs so they can stand symmetrically opposite each other (Peter and Paul, for example) and generally female saints are preferably paired with other female saints, but Catherine is one of the few who is considered so powerful that she gets to stand opposite men a lot of the time.

Catherine of Alexandria must not be confused with Saint Catherine of Siena, a Dominican nun saint from the late 14th century. Since Catherine of Alexandria wears a crown, robes and has a huge spiked wheel while Catherine of Siena wears a black and white nun’s habit, they’re easy to differentiate.

AND NOW, QUIZ YOURSELF ON SANTS YOU KNOW SO FAR:

Who do we have here?

(Brought to us by Donatello; statue in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice, done 1438)

Jump to the next Spot the Saint entry.