Spot the Saint: Agatha and Lucy

I have just returned from a jaunt through Sicily, where the change of cityscape was a perfect reminder of how useful the ability to spot saints can be. I popped into church after church, and by the fourth it was easy to tell we weren’t in Florence anymore, and not just by the prevalence of baroque frufru on the altars. San Lorenzo was scarcely anywhere to be seen, John the Baptist uncommon at best, Zenobius and Reparata distant memories, while every single church had an altarpiece or, more often, wooden statue of the two virgin martyrs Agatha and Lucy. Two guesses who are the patron saints of major cities in Sicily.

Saint Agatha (died around 250 AD)

Saint Agatha (died around 250 AD)

- Common attributes: Breasts on a platter, breasts cut off, martyr’s palm

- Occasional attributes: Pliers or pincers or big scissors, dressed in antique Roman-style robes

- Patron saint of: Victims of rape and torture, single women, wet nurses, protection against volcanic eruptions, and fire, and natural disasters in general

- Patron of places: Sicily, especially Palermo and areas where Mt. Etna’s eruptions threaten

- Feast day: February 5th

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, having her breasts ripped off

- Relics: Catania (Sicily)

Saint Agatha is, like Catherine, one of the popular set of late Roman beautiful virgin martyr saints. The story is, like many of such vintage, tangled and unreliable, and follows a fairly stock sequence of romance and persecution, but in Agatha’s case she dedicated her virginity to God but was lusted after by a Roman official, Quintinianus. He persecuted her for her rejection of him, and sent her to a brothel, but she refused to succumb. The stories have her make some very sophisticated philosophical arguments against pagan idols. Eventually he had her tortured, including having her breasts cut or ripped off, though an apparition St. Peter miraculously healed them. She died in prison.

Agatha is protector against fire because of some of the tortures she endured. This makes her extremely popular in Sicily, which is dominated by the towering volcano of Mt. Etna. Some active volcanoes sort-of sit there rather calmly, or lurk building up steam for a millennium or two before destroying Pompeii again, but not Etna. Etna erupts all the time. It erupted two or three times last year alone. Heck, it erupted while I was there, just a little eruption, but enough for the lava to trail visibly down through the snow cap like spilled ink. Now, usually it just erupts around the crater part where no one lives, but it does erupt enough to destroy some inhabited ground once every few decades, making protection against fire the top question on everyone’s minds. They have Agatha’s veil there and occasionally get it out and parade it in front of the lava as it’s coming down to try to get it to stop, and, miraculously, it sometimes does. During one such incident the veil miraculously turned from white to red, confirming its special powers.

Agatha is protector against fire because of some of the tortures she endured. This makes her extremely popular in Sicily, which is dominated by the towering volcano of Mt. Etna. Some active volcanoes sort-of sit there rather calmly, or lurk building up steam for a millennium or two before destroying Pompeii again, but not Etna. Etna erupts all the time. It erupted two or three times last year alone. Heck, it erupted while I was there, just a little eruption, but enough for the lava to trail visibly down through the snow cap like spilled ink. Now, usually it just erupts around the crater part where no one lives, but it does erupt enough to destroy some inhabited ground once every few decades, making protection against fire the top question on everyone’s minds. They have Agatha’s veil there and occasionally get it out and parade it in front of the lava as it’s coming down to try to get it to stop, and, miraculously, it sometimes does. During one such incident the veil miraculously turned from white to red, confirming its special powers.

Like many martyr saints, Agatha carries the symbols of her martyrdom, in this case usually her severed breasts on a platter. In art, the challenge is less to recognize this very distinct attribute, than to overcome the average early artist’s complete inability to visualize what breasts sitting on a platter would look like. One sees a female saint holding a tray with… are those muffins? Oranges? Bells? Bags? Little pyramidal paperweights? Oh! It’s Agatha.

Saint Lucy (Santa Lucia, 283-304 AD)

Saint Lucy (Santa Lucia, 283-304 AD)

- Common attributes: Eyeballs on a platter, eyeballs on a cup or something other than a platter, lamp or cup with a flame in it possibly also with eyeballs in it, martyr’s palm. Note that despite the eyeballs, she will still herself have eyes.

- Occasional attributes: Sword, dressed in antique Roman-style robes

- Patron saint of: Eyesight, blind people, writers (who need to read a lot!) especially Dante.

- Patron of places: Perugia, Syracuse (Sicily), Malta

- Feast day: December 13th

- Most often depicted: Standing around with other saints, especially Agatha

- Relics: Venice

Lucy was a little later than Agatha and intentionally followed her model, even receiving a visit from Agatha’s spirit. In Lucy’s case she rejected a pagan bridegroom and wanted to give her dowry to the poor. The disappointed suitor denounced her, and she was sentenced to be taken to a brothel, but became miraculously heavy, so the guards couldn’t lift her, even when they tied her to some oxen and had them pull. She was then tortured and killed.

Lucy’s name means light, and this is the source of her association with eyesight. The story of her having her eyes put out is a late addition, probably derived from the association rather than the other way around. Renaissance artists are about as bad at drawing eyeballs as they are at breasts, but they generally just paint a pair of non-ball eyes, which are much easier to recognize than Agatha’s muffins.

Lucy was Dante’s personal patron saint, so it is to she that Beatrice turned within the hierarchy of heaven when Beatrice wanted permission to give Dante his tour of the afterlife. Lucy then went to Mary, who arranged things with the King.

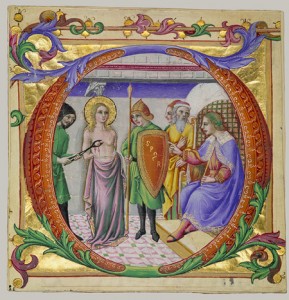

And now, Spot the Saint Quiz Time:

Quiz yourself on the saints you know so far. (click here for a higher-res image)

Sorry it’s hard to see what she’s holding. Even in the room with the original painting it’s hard to see.