Sketches of a History of Skepticism Part 3: Cicero through Scholasticism

(Best to begin with Part 1 and Part 2 of this series.)

Socrates, Sartre, Descartes and our Youth have, among them, consumed twelve thousand, six hundred and forty two hypothetical eclairs in the fourteen months since we left them contemplating skepticism on the banks of a cheerily babbling imaginary brook. Much has changed in the interval, not in the land of philosophical thought-experiments (which is ever peaceful unless someone scary like Ockham or Nietzsche gets inside), but in a world two layers of reality removed from theirs. The changes appear in the world of material circumstances which shape and foster this author, who in turn shapes and fosters our philosophical picnickers. Now, having recovered from my transplant shock of being moved to the new and fertile country of University of Chicago, and with my summer work done, and Too Like the Lightning fully revised and on its way toward its May 10th release date (YES!), it is time at last to return to our hypothetical heroes, and to my sketches of the history of philosophical skepticism.

When last we saw them, Socrates, Sartre, Descartes and our Youth had rescued themselves from the throes of absolute doubt by developing Criteria of Truth, which allowed them to differentiate arenas of knowledge where certainty is possible from arenas of knowledge where certainty is not possible. (See their previous dramatic adventures with in Sketches of a History of Skepticism Part 1 and Part 2). To do this, they looked at three systems: Epicureanism, which suggests that we have certain knowledge of the world perceived by the senses, but no certain knowledge of the imperceptible atomic reality beneath; Platonism, which suggests that we have knowledge of the eternal structures that create the material world, i.e. Forms or Ideas, but not of the flawed, corruptible material objects which are the shadows of those eternal structures; and Aristotelianism, which suggests that we can have certain knowledge of logical principles and of categories within Nature, but not of individual objects.

Notably, neither Epicurus nor Aristotle was invited to our picnic, and, while you never know when any given Socrates will turn out to be a Plato in disguise, our particular Socrates seems to be staying safely in the camp of doubt: he knows that he knows nothing. Our object is not to determine which of these classical camps has the correct Criterion of Truth. In fact, our distinguished guests, Descartes and Sartre, aren’t interested in rehashing these three classical systems all of whose criteria are not only familiar, but, to them, long defunct. They have not come through this great distance in time to watch Socrates open the doors of skepticism to our Youth to just meet antiquity’s familiar dogmatists; the twinkle in Descartes’ eye (and his infinite patience dolling out eclairs) tells me he’s waiting for something else.

Cicero Skepticus

Cicero Skepticus

Descartes and Sartre expect Cicero next — Cicero, whom many might mistake as a voice for the Stoic school (the intellectual party conspicuously missing from the assembly of Plato, Aristotle, and Epicurus) but who is actually more often read by modern scholars as a new and promising kind of Skeptic. Unfortunately, Cicero is currently busy answering a flurry of letters from someone called Petrarch, so has declined to join our little gathering (or possibly he’s just miffed hearing that I’m doing an abbreviated finale to this series, so he’d only get a couple paragraphs, even if he came). So we must do our concise best to cover his contribution on our own. Pyrrho, Zeno and other early skeptical voices argued in favor of doubt by demonstrating the fallibility of the senses and of pure reason: the stick in water that looks bent, the paradoxes of motion which show how logic and reality don’t match. Cicero achieves unbelief (and aims at the eudaimonist tranquility beyond) by a different route, a luxurious one made possible by the fact that he is writing three centuries into the development of philosophy and has many different dogmatic schools to fall back on. In his philosophical dialogs, Cicero presents different interlocutors who put forth different dogmatic positions: Stoic, Platonist, Epicurean; all in dialog with each other, presenting evidence for their own positions and counter-arguments against the conclusions of others. Each interlocutor works strictly by his own Criterion of Truth, and all argue intelligently and well. But they all disagree. When you read them all together, you are left uncertain. No particular voice seems to overtop the others, and the fact that there are so many different equally plausible positions, defended with equally well-defined Criteria of Truth, leaves one with no confidence that any of them is reliable. At no point does Cicero say “I am a skeptic, I think there is no certainty,” — but the effect of reading the dialog is to be left with uncertain feelings. Cicero himself does not seem to have been a Pyrrhonist skeptic, and certainly does seem to hold some philosophical positions, especially moral principles, quite strongly. There is certainly a good case to be made that he has strong Stoic leanings, and there is validity to the Renaissance argument that he should be vaguely clustered in with Seneca and Cato, who subscribe to a mixed-together digest of Roman paganism, Stoicism, some Platonic and a few Aristotelian elements. But especially on big questions of epistemology, ontology and physics, Cicero remains solidly, frustratingly, elusive.

There are many important aspects of Cicero’s work, but for our purposes the most important is this: he has achieved doubt without actually making any skeptical arguments, or counter-arguments. He has not attacked the fundamentals of Stoicism, Platonism or Epicureanism. Instead, he has used the strengths of the three schools to undermine each other. All three schools are convincing. All are plausible. All have evidence and/or logic on their side. As a result, none of the three winds up feeling convincing, even though none of the three has been directly undermined. This is not a new achievement of Cicero’s. Epicurus used a similar technique, and Lucretius, his follower, did so too; and we know Cicero read Lucretius. But Cicero is the most important person to use this technique in antiquity, largely because 1,300 years later it will be Cicero who become the centerpiece of Renaissance education. And Cicero will have no small Medieval legacy as well.

Medieval Certainty, and the Big Question

Medieval Certainty, and the Big Question

Stereotypically for a Renaissance historian, I will move quickly through the Middle Ages, though not for the stereotypical reasons. I don’t think that the Middle Ages were an intellectual stasis; I do think that Medieval philosophy is fully of many complex things that I’m just starting to seriously work through in my own studies. I’m not ready to provide a light, fun summary of something which is, for me, still a rich forest to explore. Church Fathers, late Neoplatonists, Chroniclers, theological councils, monastic leaders, rich injections from the Middle East, Maimonides; all intersect with doubt, certainty and Criteria of Truth in rich and fascinating ways that I am not yet prepared to do justice to. So instead I will present an abstraction of one important aspect of Medieval thinking which I hope will help elucidate some overall approaches to doubt, even if I don’t pause to look at individual minds.

When I was in my second year of grad school, I chatted over convenience store cookies in the grad student lounge with a new student entering our program that year, like myself, to study the Renaissance. He poked fun at the philosophers of the Middle Ages. He asked me, “How could anybody possibly be interested in going on and on and on and on like that about God?” And in that moment of politeness, and newness, and fun, I laughed, and nodded. But, happily, we had a good teacher who made us look more at the Medieval, without which we can’t understand the Renaissance, and now I would never laugh at such a comment.

Set aside your modern mindset for a moment, and your modern religious concepts, and see if you can jump into the Medieval mind. To start with, there is a Being of infinite power, Whose existence is known with certainty. (Take that as given — a big given, I know, but it’s a given in this context.) Such a Being created everything that ever has existed or will exist. Everything that happens: events, births, storms, falling objects, thoughts; all were conceived by this Being and exist according to this Being’s script. The Being possesses all knowledge, and all good things are good because they resemble this Being. Everything in the material world is fleeting and imperfect and will someday be destroyed and forgotten, including the entire Earth. But — this Being has access to another universe where all things are eternal and perfect, which will last beyond the end of the material universe, and with this Being’s help there might be some way for us to reach that universe as well. The Being created humans with particular care, and is trying to communicate with us, but direct communication is a difficult process, just as it is difficult for an entomologist to communicate directly with his ants, or for a computer programmer to communicate directly with the artificial intelligences that she has programmed.

Now, the facetious question I laughed at in early grad school comes back, but turned on its head. How could you ever want to study anything other than this Being? It explains everything. You want to know the cause of weather, astronomical events, diseases, time? The answer is this Being. You want to know where the world came from, how thought works, why there is pain? The answer is this Being. History is a script written by this Being, the stars are a diagram drawn by this Being, the suitability and adaptation of animals and plants to their environments is the ingenuity of this Being, and the laws that make rocks sink and wood float and fire burn and rain fall are all decisions made by this Being. If you have any intellectual curiosity at all, wouldn’t it be an act of insanity to dedicate your life to anything other than understanding this Being? And in a world in which there has been, for centuries, effective universal consensus on all these premises, what society would want to fund a school that didn’t study them? Or pay tuition for a child to study something else? Theology dominated other sciences in the Middle Ages, not because people were backward, or closed-minded, or lacked curiosity, but because they were ambitious, keenly intellectual and fixed on the a subject from which they had every reason to expect answers, not just to theological questions, but to all questions. They didn’t have blinders, they had their eyes on the prize, and they felt that choosing to study Natural Philosophy (i.e. the world, nature, biology, plants, animals) instead of Theology was like trying to study toenail clippings instead of the being they were clipped from.

To put it another way: have you ever watched a fun, formulaic, episodic genre show like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, or the X-Files? There’ll be one particular episode where the baddie-of-the-day is Christianity-flavored, and at some point a manifest miracle happens, or an angel or a ghost shows up, and then we have to reset the formula and move onto the next episode, but you spend that whole next episode thinking, “You know, they just found proof of the existence of the afterlife and the immortality of the soul. You’d think they’d decide that’s more important than this conspiracy involving genetically-modified corn.” That’s how people in the Middle Ages felt about people who wanted to study things that weren’t God.

Doubt comes into this in important ways, but not the ways that modern rhetoric about the Middle Ages leads most people to expect.

Why Scholasticism?

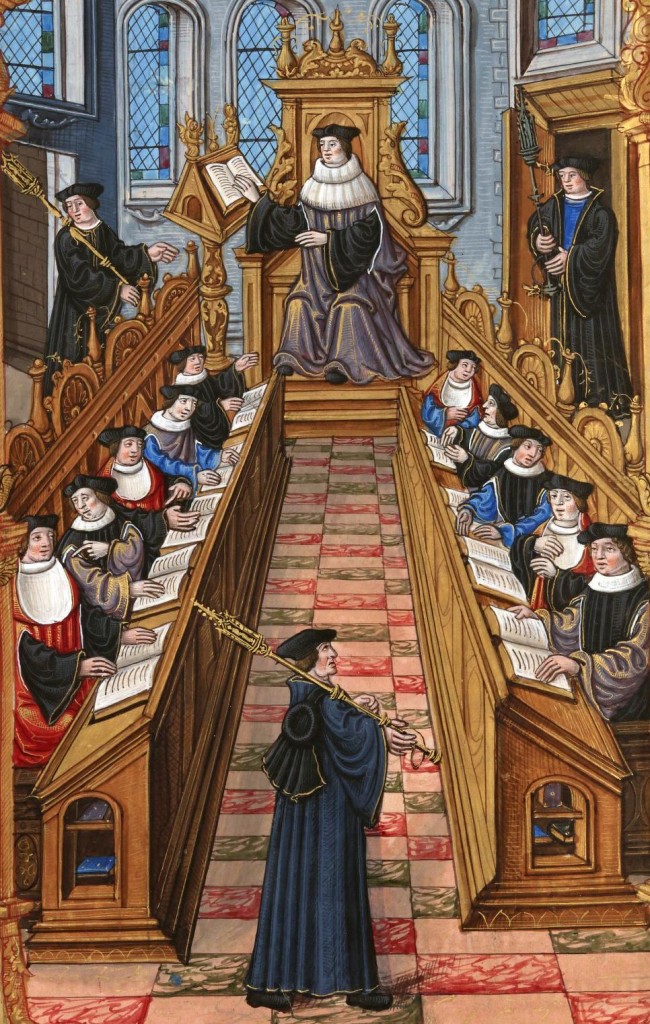

Wikipedia, at the time of writing, defines Scholasticism as “a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics (“scholastics,” or “schoolmen”) of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. ” It was “a program of employing that [critical] method in articulating and defending dogma in an increasingly pluralistic context.” It “originated as an outgrowth of, and a departure from, Christian monastic schools at the earliest European universities.” Philosophy students traditionally define Scholasticism as “that incredibly boring hard stuff about God that you have to read between the classics and Descartes”. Both definitions are true. Scholasticism is an incredibly tedious, exacting body of philosophy, intentionally impenetrable, obsessed with micro-detail, and happy to spend three thousand words proving to you that Good is good, or to set out a twenty step argument it is better to exist than not exist (this is presumably why Hamlet still hadn’t graduated at age 30). Scholasticism was also so incredibly exciting that, apart from the ever-profitable medical and law schools, European higher education devoted itself to practically nothing else for the whole late Middle Ages, and, even though the intellectual firebrands of both the Renaissance and the 17th and 18th centuries devoted themselves largely to fiercely attacking the scholastic system, it did not truly crumble until deep into the Enlightenment.

Why was Scholasticism so exciting? Even if people who believed in an omnipotent God had good reason to devote their studies pretty-exclusively to Theology, why was this one particularly dense and intentionally difficult method the method for hundreds of years? Why didn’t they write easy-to-read, penetrable treatises, or witty philosophical tales, or even a good old fashioned Platonic-type dialog?

The answer is that Christianity changes the stakes for being wrong. In antiquity, if you’re wrong about philosophy, and the philosophical end of theology, you’ll make incorrect decisions, possibly lead a sadder or less successful life than you would otherwise, and it might mean your legacy isn’t what you wanted it to be, but that’s it. If you’re really, really wrong you might offend Artemis or something and get zapped, but it’s pretty easy to cover your bases by going to the right festivals. By the logic of antiquity, if you put a Platonist and an Epicurean in a room, one of of them will be wrong and living life the wrong way, at least in some ways, but they can both have a nice conversation, and in the end, either they’ll both reincarnate and the Epicurean will have another chance to be right later, or they’ll both disperse into atoms and it won’t matter. OK. In Medieval Christianity, if you’re wrong about theology, your immortal soul goes to Hell forever, where you’ll be tormented by unspeakable devils for the rest of eternity, and everyone else who believes your errors is also likely to lose the chance of eternal paradise and absolute knowledge, and will be plunged into a pit of absolute misery and despair, irrevocably, forever. Error is incredibly dangerous, to you and to everyone around you who might get pulled down with you. If you’re really bad, you might even bring the wrath of God down upon your native city, or if you’re really bad then, while you’re still alive, your soul might depart your body and sink down to Hell, leaving your body to be a house for a devil who will use you to visit evil on the Earth (see Inferno Canto 27). But leaving aside those more extreme and superstition-tainted possibilities, error became more pernicious because of eternal damnation. If people who read your theologically incorrect works go to Hell, you’re infinitely culpable, morally, since every student misled to damnation is literally an infinite crime.

So, if you are a Medieval person, Theology is incredibly valuable, the only kind of study worth doing, but also incredibly dangerous. You want to tread very carefully. You want a lot of safety nets and spotters. You want ways to avoid error. And you know error is easy! Errors of logic, errors of failing senses. Enter Aristotle, or more specifically enter Aristotle’s Organon, a translation of the poetic works of Aristotle completed by dear Boethius, part of the latter’s efforts to preserve Greek learning when he realized Greek and other relics of antiquity were fading. The Organon explains in great detail, how you can go about constructing chains of logic in careful, methodical ways to avoid error. Use only clearly defined unequivocal vocabulary, and strict syllogistic and geometric reasoning. Here it is, foolproof logic in 50 steps, I’ll show you! Sound familiar? This is Aristotle’s old Criterion of Truth, but it’s also the Medieval Theologian’s #1 Christmas Wish List. The Criterion of Truth which was, for Aristotle, a path through the dark woods and a solution to Zeno and the Stick in Water, is, to our theologian, a safety net over a pit of eternal Hellfire. That is why it was so exciting. That was why people who wanted to do theology were willing to train for five years just in logic before even looking at a theological question, just as Astronauts train in simulators for a long time before going out into the deadly vacuum of space! That is even why scholastic texts are so hard to read and understand – they were intentionally written to be difficult to read, partly because they’re using an incredibly complicated method, but even more because they don’t want anyone to read them who hasn’t studied their method, because if you read them unprepared you might misunderstand, and then you’d go to Hell forever and ever and ever, and it would be Thomas Aquinas’s fault. And he would be very sad. When Thomas Aquinas was presented for canonization, after his death, they made the argument that every chapter of the Summa Theologica was itself a miracle. It’s easy to laugh, but if you think about how desperately they wanted perfect logic, and how good Aquinas was at offering it, it’s an argument I understand. If you were dying of thirst in the desert, wouldn’t a glass of water feel like a miracle?

To give credit where credit is due, the mature application of Aristotle’s formal logic to theological questions was not pioneered by Aquinas but by a predecessor: Peter Abelard, the wild rockstar of Medieval Theology. People crowded in thousands and lived in fields to hear Peter Abelard preach, it was like Woodstock, only with more Aristotle. Why were people so excited? Did Abelard finally have the right answer to all things? “Yes and No,” as Peter Abelard would say, “Sic et Non“, that being the the title of his famous book, a demonstration of his skill. (Wait, yes AND no, isn’t that even scarier and worse and more damnable than everything else? This is the most dangerous person ever! Bernard of Clairvaux thought so, but the Woodstock crowd at the Paraclete, they don’t.) Abelard’s skill was taking two apparently contradictory statements and showing, by elaborate roundabout logic tricks, how they agree. Why is this so exciting? Any troll on the internet can do that! No, but he did it seriously, and he did it with Authorities. He would take a bit of Plato that seemed to contradict a bit of Aristotle, and show how they actually agree. Even ballsier, he would take a bit of Plato that pretty manifestly DOES contradict another bit of Plato, and show how they both agree. Then, even better, he would take a bit from St. Augustine that seems to contradict a bit from St. Jerome and show how the two actually agree. “OH THANK GOD!” cries Medieval Europe, desperately perplexed by the following conundrum:

To give credit where credit is due, the mature application of Aristotle’s formal logic to theological questions was not pioneered by Aquinas but by a predecessor: Peter Abelard, the wild rockstar of Medieval Theology. People crowded in thousands and lived in fields to hear Peter Abelard preach, it was like Woodstock, only with more Aristotle. Why were people so excited? Did Abelard finally have the right answer to all things? “Yes and No,” as Peter Abelard would say, “Sic et Non“, that being the the title of his famous book, a demonstration of his skill. (Wait, yes AND no, isn’t that even scarier and worse and more damnable than everything else? This is the most dangerous person ever! Bernard of Clairvaux thought so, but the Woodstock crowd at the Paraclete, they don’t.) Abelard’s skill was taking two apparently contradictory statements and showing, by elaborate roundabout logic tricks, how they agree. Why is this so exciting? Any troll on the internet can do that! No, but he did it seriously, and he did it with Authorities. He would take a bit of Plato that seemed to contradict a bit of Aristotle, and show how they actually agree. Even ballsier, he would take a bit of Plato that pretty manifestly DOES contradict another bit of Plato, and show how they both agree. Then, even better, he would take a bit from St. Augustine that seems to contradict a bit from St. Jerome and show how the two actually agree. “OH THANK GOD!” cries Medieval Europe, desperately perplexed by the following conundrum:

- The Church Fathers are saints, and divinely inspired; their words are direct messages from God.

- If you believe the Church Fathers and act in accordance with their teachings, they will show you the way to Heaven; if you oppose or doubt them, you are a heretic and damned for all eternity.

- The Church Fathers often disagree with each other.

- PANIC!

Abelard rescued Medieval Europe from this contradiction, not necessarily by his every answer, but by his technique by which seemingly-contradictory authorities could be reconciled. Plato with Aristotle is handy. Plato with Plato sure is helpful. Jerome with Augustine is eternal salvation. And if he does it with the bits of Scripture that seem to contract the other bits? He is now the most exciting thing since the last time the Virgin Mary showed up in person.

Abelard had a lover–later, wife, but she preferred ‘lover’–the even more extraordinary Heloise, and I consider it immoral to mention him without mentioning her, but her life, her stunningly original philosophical contributions and her terrible treatment at the hands of history are subjects for another essay in its own right. For today, the important part is this: Abelard was exciting for his method, more than his ideas, his way of using Reason to resolve doubts and fears when skepticism loomed. Thus even Scholasticism, the most infamously dogmatic philosophical method in European history, was also in symbiosis with skepticism, responding to it, building from it, developing its vast towers of baby-step elaborate logic because it knew Zeno was waiting.

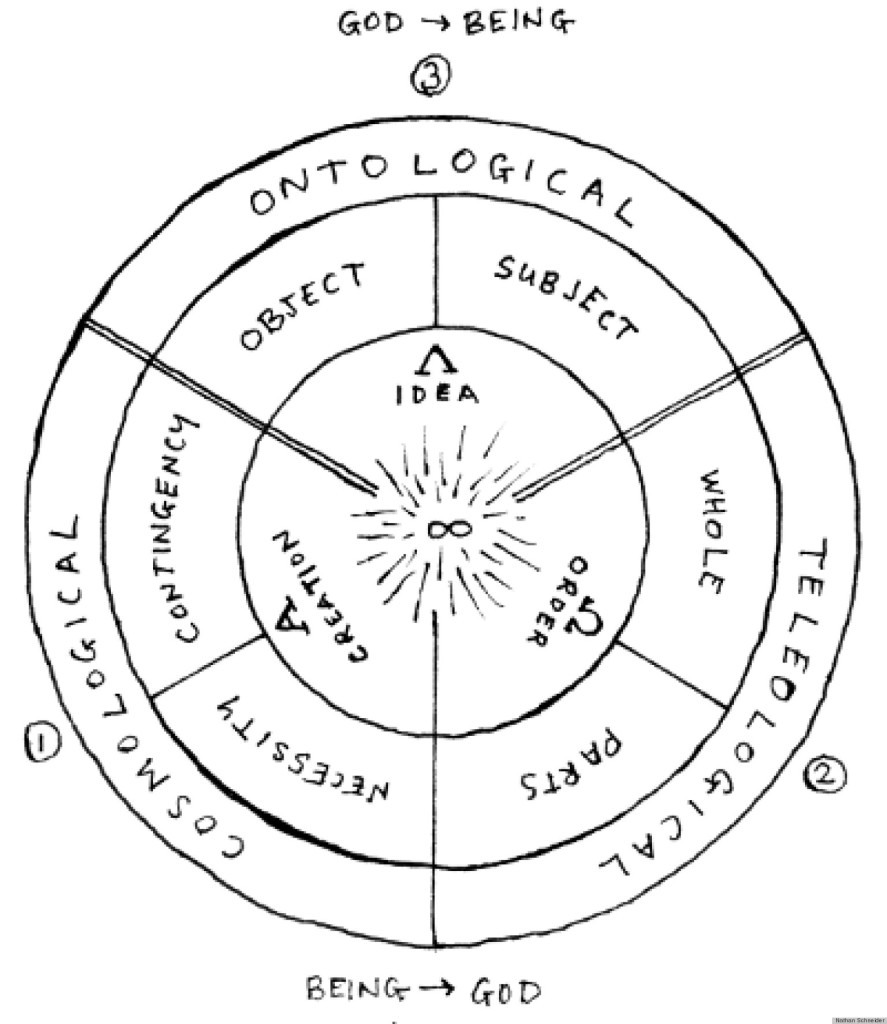

Proofs of the Existence of God

We are all very familiar with the veins of Christianity which focus on faith without proof as an important part of the divine plan, that God wants to test people, and there is no proof of the existence of God because God wants to be unknowable and elusive in order to test people’s faith. The most concise formula is the facetious one by Douglas Adams, where God says: “I refuse to prove that I exist, because proof denies faith and without faith I am nothing.” It’s a type of argument associated with very traditional, conservative Christianity, and, often, with its more zealous, bigoted, or “medieval” side. I play a game whenever I run into a new scholar who works on Medieval or early modern theological sources, any sources, any period, any place, from pre-Constantine Rome to Renaissance Poland. I ask: “Hey, have you ever run into arguments that God’s existence can’t be proved, or God wants to be known by faith alone, before the Reformation?” Answers: “No.” “Nope.” “Naah.” “No, never.” “Uhhh, not really, no.” “Nope.” “No.” “Nothing like that.” “Hmm… no.” “Never.” “Oh, yeah, one time I thought I found that in this fifth-century guy, but actually it was totally not that at all.” Like biblical literalism, it’s one of these positions that feels old because it’s part of a conservative position now, but it’s actually a very recent development from the perspective of 2,000 years of Christianity plus centuries more of earlier theological conversations. So, that isn’t what the Middle Ages generally does with doubt; it doesn’t rave about faith or God’s existence being elusive. Europe’s Medieval philosophers were so sure of God’s existence that it was considered manifestly obvious, and doubting it was considered a mental illness or a form of mental retardation (“The fool said in his heart ‘there is no God’,” => there must be some kind of brain deficiency which makes people doubt God; for details on this a see Alan C. Kors, Atheism in France, vol. 1). And when St. Anselm and Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus work up technical proofs of the existence of God they’re doing it, not because they or anyone was doubting the existence of God, but to demonstrate the efficacy of logic. If you invent a snazzy new metal detector you first aim it at a big hunk of metal to make sure it works. If you design a sophisticated robot arm, you start the test by having it pick up something easy to grab. If you want to demonstrate the power of a new tool of logic, you test it by trying to prove the biggest, simplest, most obvious thing possible: the existence of God.

(PARENTHESIS: Remember, I am skipping many Medieval things of great importance. *cough*Averroes*cough* This is a snapshot, not a survey.)

Three blossoms on the thorny rose of this Medieval trend toward writing proofs of the existence of God are worth stopping to sniff.

The first blossom is the famous William of Ockham (of “razor” fame) and his “anti-proof” of the existence of God. Ockham was a scholastic, writing in response to and in the same style and genre as Abelard, Aquinas, Scotus, and their ilk. But, when one read along and got to the bit where one would expect him to demonstrate his mastery of logic by proving the existence of God, he included instead a plea (paraphrase): Please, guys, stop writing proofs of the existence of God! Everyone believes in Him already anyway. If you keep writing these proofs, and then somebody proves your proof wrong by pointing out an error in your logic, reading the disproof might make people who didn’t doubt the existence of God start to doubt Him because they would start to think the evidence for His Existence doesn’t hold up! Some will read into this Anti-Proof hints of the beginning of “God will not offer proof, He requires faith…” arguments, and perhaps it does play a role in the birth of that vein of thinking. (I say this very provisionally, because it is not my area, and I would want to do a lot of reading before saying anything firm). My gut says, though, that it is more that Ockham thought everyone by nature believed in God, that God’s existence was so incredibly obvious, that God was not trying to hide, rather that he didn’t want the weakness of fractious scholastic in-fighting to erode what he thought was already there in everyone: belief.

Aside: While we are on the subject of Ockham, a few words on his “razor”. Ockham is credited with the principle that the simplest explanation for a thing is most likely to the correct one. That was not, in fact, a formula he put forward in anything like modern scientific terms. Rather, what we refer to as Ockham’s Razor is a distillation of his approach in a specific argument: Ockham hated the Aristotelian-Thomist model of cognition, i.e. the explanation of how sense perception and thoughts work. Hating it was fair, and anyone who has ever studied Aristotle and labored through the agent intellect, and the active intellect, and the passive intellect, and the will, and the phantasm, and innate ideas, and eternal Ideas, and forms, and categories, and potentialities, shares William of Ockham’s desire to pick Thomas Aquinas up and shake him until all the terminology falls out like loose change, and then tell him he’s only allowed to have a sensible number of incredibly technical terms (like 10, 10 would be a HUGE reduction!). Ockham proposed a new model of cognition which he set out to make much simpler, without most of the components posited by Aristotle and Aquinas, and introduced formal Nominalism. (Here Descartes cheers and sets off a little firecracker he’s been saving). Nominalism is the idea that “concepts” are created by the mind based on sense experience, and exist ONLY in the mind (like furniture in a room, adds Sherlock Holmes) rather than in some immaterial external sense (like Platonic forms). Having vastly simplified and revolutionized cognition, Ockham then proceeded to describe the types of concepts, vocabulary terms and linguistic categories we use to refer to concepts in infuriating detail, inventing fifty jillion more technical terms than Aquinas ever used, and driving everyone who read him crazy. (If you are ever transported to a dungeon where you have to fight great philosophers personified as Dungeons & Dragons monsters, the best weapon against Ockham is to grab his razor of +10 against unnecessary terminology and use it on the man himself). One takeaway note from this aside: while “Ockham’s Razor” is a popular rallying cry of modern (post-Darwin) atheism, and more broadly of modern rationalism, that is a modern usage entirely unrelated to the creator himself. He thought that the existence of God was so incredibly obvious, and necessary to explain so many things, from the existence of the universe to the buoyancy of cork, that if you presented him with the principle that the simplest explanation is usually best, he would agree, and happily assume that you believed, along with him, that “God” (being infinitely simple, see Plotinus and Aquinas) is therefore a far simpler answer to 10,000 technical scientific questions than 10,000 separate technical scientific answers. Like Machiavelli, Aristotle and many more, Ockham would have been utterly stunned (and, I think, more than a little scared) if he could have seen how his principles would be used later.

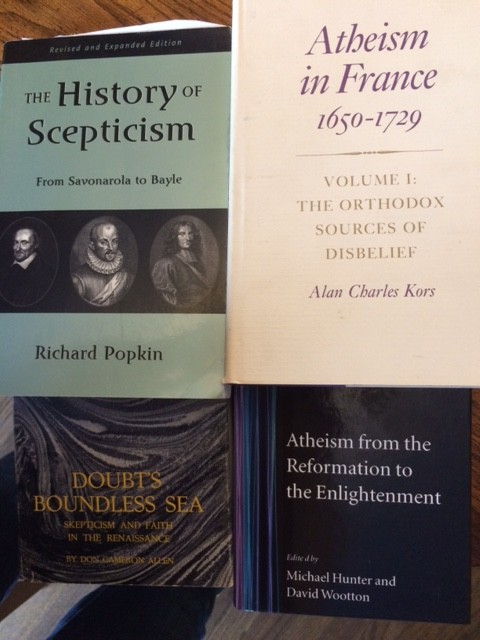

The second blossom (or perhaps thorn?) of this Medieval fad of proving God’s existence was, well, that Ockham was 110% correct. Here again I cite Alan Kors’ masterful Atheism in France; in short, his findings were that, when proving the existence of God became more and more popular, as the first field test to make sure your logical system worked, (a la metal detector…beep, beep, beep, yup it’s working!), it created an incentive for competing logicians to attack people’s proofs of the existence of God (i.e. if it can’t find a giant lump of iron the size of a house it’s not a very good metal detector, is it?) Thus believers spent centuries writing attacks on the existence of God, not because they doubted, but to prove their own mastery of Aristotelian logic superior to others. This then generated thousands of pages of attacks on the existence of God, and, by a bizarre coincidence *cough*cough*, when, in the 17th and 18th centuries, we finally do start getting writings by actual overt “I really think there is no God!” atheists, they use many of the same arguments, which were waiting for them, readily available in volumes upon volumes of Church-generated books. Dogmatism here fed and enriched skepticism, much as skepticism has always fed and enriched dogmatism, in their ongoing and fruitful symbiosis.

The third blossom is, of course, sitting with us dolling out eclairs. Impatient Descartes has been itching, ever since I mentioned Anselm, to leap in with his own Proof of the Existence of God, one which uses a more mature form of Ockham’s Nominalism, coupled with the tools of skepticism, especially doubt of the senses. But Descartes may not speak yet! (Don’t make that angry face at me, Monsieur, you’ll agree when you hear why.) It won’t be Descartes’ turn until we have reviewed a few more details, a little Renaissance and Reformation, and introduced you to Descartes’ great predecessor, the fertile plain on whom Descartes will erect his Cathedral. Smiling now, realizing that we draw near the Illustrious Father of Skeptics whom he has been waiting for, Descartes sits back content, until next time.

But do not fear, the wait will be short this time. Socrates is in more suspense than Descartes, and if I stop writing he’ll start demanding that I define “illustrious” or “next” or “man”, so I’d better plunge straight in. Meanwhile, I hope you will leave this little snapshot with the following takeaways:

-

Angels at a Last Judgment (in Berlin) sorting correct souls from souls guilty of ERROR! Medieval thought was not dominated by the idea that logic and inquiry are bad and Blind Faith should rule; much more often, Medieval thinkers argued that logic and inquiry were wonderful because they could reinforce and explain faith, and protect people from error and eternal damnation. Medieval society threw tons of energy into the pursuit of knowledge (scientia, science), it’s just that they thought theology was 1000x more important than any other topic, so concentrated the resources there.

- When you see theologians discussing whether certain areas of knowledge are “beyond human knowledge” or “unknowable”, before you automatically call this a backwards and closed-minded attitude, remember that it comes from Plato, Epicurus and Aristotle, who tried to differentiate knowledge into areas that could be known with certainty, and areas where our sources (senses/logic) are unreliable, so there will always be doubt. The act of dividing certain from uncertain only becomes close-minded when “that falls outside what can be known with certainty” becomes an excuse for telling the bright young questioner to shut up. This happened, but not always.

- Even when there were not many philosophers we could call “skeptics” in the formal sense, and the great ancient skeptics were not being read much, skepticism continued to be a huge part of philosophy because the tools developed to combat it (Aristotle’s logical methods, for example) continued to be used, expanded and re-purposed in the ongoing search for certainty.

- Remember Cicero; he’ll be back.

Continue to Part 4: The Renaissance, Montaigne and a touch of Voltaire.