A Rose for Rodrigo Borgia (guest post)

Note: this is a guest post. I am on another research jaunt, speaking in Rome and Oxford and visiting an intriguing book in Paris. While I’m travel-swamped, a good friend, Rush-That-Speaks, has agreed to write a guest post, describing a little Roman adventure we shared.

Note: this is a guest post. I am on another research jaunt, speaking in Rome and Oxford and visiting an intriguing book in Paris. While I’m travel-swamped, a good friend, Rush-That-Speaks, has agreed to write a guest post, describing a little Roman adventure we shared.

Rush-That-Speaks writes:

The last time “Ex Urbe” and I were in Rome together, which was late in November of 2011, we were sitting in our hotel room one moderately tired evening, and, as one does, were discussing the Borgias. I believe that this was in the context initially of the Borgia arms, which are stamped on everything the family sponsored in Rome during Rodrigo’s papacy (1492-1503). The coat of arms of the reigning pope also gets put up at all the churches where the pope is a regular celebrant, and not taken down no matter how many centuries go by, and sometimes popes just put their arms up on things because they’re pope and they can and it’s a Statement. The Borgia bull, therefore, is pretty common throughout the City, along with various other Renaissance great houses who at some point took the papacy: Medici and della Rovere and so on. Honestly these tend to be in better taste than more recent stamps-of-arms; Benedict’s arms came out a rather nasty shade of fuchsia. So we were talking about places we’d spotted the bull that day, surprising and otherwise, and how annoying it is that Cesare Borgia is buried over in Spain where people who have been traveling through all the scenes of his life in Italy cannot easily go and look at him. [Ex Urbe Note: Reminder regarding Cesare’s tomb, he was originally buried in the Church of Santa Maria in Viana but in 1537 the bishop had the tomb destroyed and his remains buried in unconsecrated ground, as (many thought at the time) such sinful monsters deserve. In 2007, on the 500th anniversary of his death, the Archbishop currently in charge of the site had Cesare dug up and moved back into a proper tomb again, partly on the theory that 500 years’ exile was enough even for such a monster, and because it was a publicity and tourism coup. Lucrezia is in the castle in Ferrara with her last husband, Alfonso d’Este]

Which led to contemplation of the death of Cesare Borgia, purulent with syphilis and defeated but still fighting as he was, and then to the anecdote about the seven devils who came to Rodrigo Borgia’s deathbed to bear him off when his time for plaguing the world was finished (a fairly well-accepted bit of gossip); and then a question occurred which had never really crossed either of our minds before, namely, if Cesare is off in Spain, then where is Rodrigo Borgia buried?

If you want a papal tomb of course you traditionally look in St. Peter’s. He wouldn’t be in the upper level, the church itself, because you have to be a saint or at least beatified to be buried in that part at all. Many popes who have not yet achieved sainthood but hope for it are buried in hopeful little tombs in the basement crypts, and then whenever one of them is exalted in status he is moved upstairs and showered in triumphant statuary. But it’s not as though there’s a morals requirement for being buried in the basement. Boniface VIII is down there, the pope Dante spent several cantos calling the Antichrist, and Boniface is even buried with his nephew, the one whose appointment as Cardinal gives us the word ‘nepotism’, from nepos, nephew.

However, if Rodrigo were in the basement of St. Peter’s either “Ex Urbe” or myself would have heard about it at some point. St. Peter’s is a very heavily documented and famous place, discussed by artists and architects throughout history. There are explanatory books and pamphlets about it sold maybe every fifty feet in the City of Rome, there are guided tours, there are non-guided tours, and at some point in some way one of us would have come across the fact of him if he were in there, even if he were in a portion never open to the public.

So we looked it up. Rodrigo Borgia is buried in Santa Maria in Monserrato degli Spagnoli, the Church of Holy Mary in Monserrat of the Spaniards, which is the official Spanish church in Rome. By this I mean it is the church in which Spanish dignitaries in Rome conduct their ceremonies, and the church which is specially charged to look after Spanish travelers in distress, and, most importantly, where famous Spaniards who die in Rome are buried. Many countries have such churches in Rome, and so do several professions– the official sailors’ church in Rome is very close to S. Maria in Monserrato, and so is the official Russian church (a more surprising object). It is not, however, a very prestigious place to be buried, not if you are a Pope. The reason why is tomb desecration: people kept trying it. They’d put Rodrigo in one place, and someone would desecrate the site, and then they’d move him, and it would happen again, and it just kept happening, so they moved Rodrigo and the previous Borgia Pope, Callixtus III, who was somewhat better liked, into the Spanish church. And didn’t mark the place. And buried them together. And hoped that would do it. [Note from Ex Urbe: There are reports of Alexander’s immediate successors, especially Julius II, refusing to let him be in St. Peter’s, and Julius even ordered that all Borgia tombs be opened, but the vandalism seems to have been not only fast but also frequent and consistent over decades.]

It’s marked now, because in the middle nineteenth century a fairly popular King of Spain died in Rome, and when they buried Alonzo XIII next to the Borgias they figured they’d better put up a mausoleum so everybody knew who was where. The body of the King of Spain has since been repatriated, but apparently no one is angry enough to desecrate a Borgia tomb anymore, so the plaque for Rodrigo and Callixtus remains.

This meant we could go over and leave Rodrigo some flowers. I was curious to see whether anybody else would have.

We started by going over to the Campo de’ Fiori, which is the flower market of Rome. It’s also an open-air market for a lot of other things, the usual tourist souvenirs but also a very good produce and farmers’ market with a wide selection of seasonal fruits and vegetables in the early mornings, and in the center it has the monument to Giordano Bruno on the spot where he was burned at the stake for heresy. A thing it is pleasant to do, and which I had done earlier in the trip, is to buy fruit from the market, such as one of the kaki, the big sweet orange Italian persimmons, and sit on Bruno’s plinth and eat it looking at him. He is usually covered in pigeons, as are many statues in Rome, but he looks less indignant about it than most of them. But that day we had to figure out what kind of flower you take to the grave of Seriously The Most Evil Pope. The flower market is not seasonally restricted the way the rest of the market is, and is basically open-air florist’s shops, so you can really get just about anything. An orchid might be overdoing it a little? What seemed most appropriate was a single dark red rose, though in the end a small cluster of coral-colored roses was the best we could acquire.

We started by going over to the Campo de’ Fiori, which is the flower market of Rome. It’s also an open-air market for a lot of other things, the usual tourist souvenirs but also a very good produce and farmers’ market with a wide selection of seasonal fruits and vegetables in the early mornings, and in the center it has the monument to Giordano Bruno on the spot where he was burned at the stake for heresy. A thing it is pleasant to do, and which I had done earlier in the trip, is to buy fruit from the market, such as one of the kaki, the big sweet orange Italian persimmons, and sit on Bruno’s plinth and eat it looking at him. He is usually covered in pigeons, as are many statues in Rome, but he looks less indignant about it than most of them. But that day we had to figure out what kind of flower you take to the grave of Seriously The Most Evil Pope. The flower market is not seasonally restricted the way the rest of the market is, and is basically open-air florist’s shops, so you can really get just about anything. An orchid might be overdoing it a little? What seemed most appropriate was a single dark red rose, though in the end a small cluster of coral-colored roses was the best we could acquire.

Then to find the church. It is not easy to find a single church in Rome. Any given block will have between two and five of them. The internet told us that S. Maria in Monserrato was on a street called the Via Giulia, pretty much due west of the Campo de’ Fiori, south of the Corso Vittorio Emanuele and south-east of the Mazzini bridge. The Via Giulia is a fairly long street, running north-west to south-east, in a quiet little quarter between Everything Historic and the river. We found the street itself pretty easily, and it turns out to be a sheltered backwater of a neighborhood, somewhat residential but mostly centered on antique shops and obscure churches of precisely the sort we were looking for. We went into several antique shops, as “Ex Urbe” is on a years’-long quest for an affordable piece of porphyry, and the thing I will never quite forget about the Via Giulia was the way every single antique shop reeked desperately of a different flavor of incredibly penetrating cigarette smoke. It was astonishing. I would have been afraid to buy stone tablets from some of those places for fear of the smell having seeped into solid rock. But the owners were friendly and knowledgeable and good at their professions, which means of course that there was no affordable porphyry, because no one good at the profession of antiquing would permit such a thing to happen. [Ex Urbe note: had I been 900 euros richer, I might have left one shop 900 euros poorer with the most beautiful marble tile inlaid with spiraling triangular chips porphyry and serpentine… I can still see it if I close my eyes… just like the Sistine Chapel floor. Have I griped recently about how hard it is to find a photo of the Sistine Chapel floor?]

There were also signs up and down the Via Giulia talking about celebrating the neighborhood, and the artistic and antique beauty of the quarter and its long history, and these signs had on them a portrait of… could it be? Does irony work in such mysterious ways? Was Rodrigo Borgia, Alexander VI, The Most Evil Renaissance Pope, really buried on a street named for Pope Julius II, Giuliano della Rovere, Rodrigo’s successor to the papacy and rival, enemy and heir? Della Rovere who fled to France when Rodrigo was elected, for fear of poison, della Rovere who brought Charles VIII of France back with him to conquer Italy, so mad was he to see it taken from the Borgias? (It didn’t work. Rodrigo bought the right people in the King of France’s cabinet: Charles conquered, but did not depose the papacy.) Via Giulia. There was his picture on every signpost banner. How remarkable.

Except of course that we couldn’t find the church anywhere. As I mentioned, the street is a long one, and we went up and down it two or three times, from the Official Church Of The Florentines In Rome at one end of it to the bit where it peters vaguely out near the river at the other end. [Ex Urbe note: of course Florentines need their own Church in Rome: S.P.Q.F!] There are a lot of little churches, all with similar facades, white and severe with the same kinds of inset columns, the same triangular pediments, the names carved neatly into the marble somewhere or other, but no facade that matched the one we’d seen on the internet, and no remotely similar name. It was beginning to get late, on a November evening which was starting to aim for freezing, and the first few people we asked had no idea either.

It was an antique-shop owner who told us, finally, that of course Via Giulia as the address of the church didn’t mean it fronted on the Via Giulia; it has its unmarked back to that street. No, it fronts on the Via Monserrato, one street easterly, and we’d walked by the back at least four times. We located it, and there indeed it sat, the white facade, the inset columns, the neat blank triangle pediment, the carved correct name, and the sign on the door saying that it is open only for Masses at seven and nine a.m. Sundays.

This is not actually that uncommon a situation with churches in Italy. They do not always enjoy being treated as art objects and goals for a tourist tramp. They are part of a living religion and tradition and would like that respected, and also they haven’t got the manpower to keep everything open all the time, because there are just too many churches for that to be possible. A small, obscure church might only be open for Mass on its saints’-day, or every other Sunday, or every third week, or whenever it is part of the rounds of the local bishop, maybe every few months. Open every Sunday actually indicates that S. Maria in Monserrato has a devoted and habitual congregation, quite possibly composed of the expatriate Spaniard community for whom it was originally built. We had had to give up all hope of seeing the grill of St. Lawrence earlier in the trip, because the church where that is kept opens once a year officially and we couldn’t figure out what door nearby it might lead to someone with the ability to let us in. There’s a church with a Michelangelo in it in Florence which is practically a landmark because of the crowds of tourists standing around it trying to figure out why it is inexplicably closed all the time; “Ex Urbe”’s lived in Florence for more than one year of her life and never gotten in there, and no helpful signs, either. [Ex Urbe note: Someday I will be there on Good Friday, when ALL Churches are required to open their doors to everyone. Then I will go in and perniciously look at all the art! Wahaha! Wahahahaha!]

But fortunately, we had tramped out to find Rodrigo Borgia on a Saturday afternoon, and Sunday lay before us. So we hauled ourselves out of bed on Sunday morning, and were at the church doors just before nine a.m., and they were open.

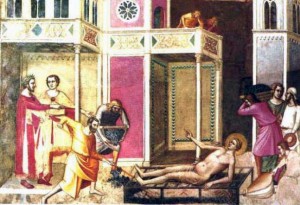

Now, any Mass at a church of this sort is open to anybody, but it is rude to hang around for very long if you are not actually going to go to the service, and it is very rude to wander around a lot taking pictures and gawking and then leave visibly. We did not even go up to the front. There may well be some decent statuary or painting in there somewhere, but we did not see it, because we went straight to the Borgia tomb, which luckily is in the first niche on the right-hand side, and stayed there, out of the way of the entering crowd. There’s a railing keeping you out of the actual niche, and the tomb itself is well back in the niche, in the right-hand-side wall, so in order to see it you have to stand with your back to the front of the church (and the altar) and crane your neck over, which seems appropriate. It’s a chaste enough marble tomb, done up like a little Greek temple, with relief busts of Rodrigo and Callixtus and a model stone pope hat, the Borgia bull three times and no motto. The tomb of the Spanish king, which is under it, is very much more mourning-centered and has a motto about how much his people loved him; I am pretty sure the contrast was intentional.

“Ex Urbe” is taller than I am and has better aim, so she leaned over the railing at an angle and then tossed the rose. It landed well, on the floor in front of the tomb. There weren’t any other flowers in sight. We slipped out of the church just as the doors were shutting and Mass was about to start, blinking into the bright morning. Speculating over whether, when they came to clean the niches, the staff would think the rose was for the King of Spain, and whether this happens often. I somehow think it doesn’t.

So Rodrigo is buried facing the Via Giulia, and the church he’s in is facing away from it, but also actually on it. This is very much the way the City of Rome turns out to work, sometimes. Like how Caesar was stabbed on the messiest junction of the overground tram tracks, a gentle and unmarked unintentional joke upon history. I am not entirely certain it is worth going out of your way for his tomb, as a tourist, unless you are the way we are about the Borgias and happen to have a free Sunday morning, but it was certainly worth it to us, and the option is there for those who may want it.

(Rush-That-Speaks writes book reviews of sci-fi and fantasy literature, and blogs about many things including reading an impressive range of books, a lot of genre topics. She recently completed a project to read 365 books in 365 days, a fascinating and impressive undertaking. You can find her own blog here, or hosted through LiveJournal.)

Related: Read about the Borgias in TV Drama.